Dispatch: The Arrow of Time

Returning to The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life for the last session of ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ Catherine Morland thinks through the ways in which modern, Western art museums sever artworks, and their publics, from the worlds that they are part of.

Many of our meetings take place at The Experimental Research Station for Art and Life, a plot of land being transformed into a sustainable and ecological outdoor garden and project space in Siliștea Snagovului, a village 30 miles north of Bucharest. Our first session took place not long after the outbreak of the brutal attacks on Gaza that we still see unfolding now. If we need a reason to embrace non-western technologies for the good life, this global awakening to the complicity of western minds to enable genocide is surely it.

The station is introduced to us as a pause, a ground zero, a place to take stock and reflect, where time stands still long enough for us to think about the space between the so-called East and West. I see it as a place to think about my inherited positionality and readjust myself accordingly, physically as well as theoretically. As a white Western European-educated woman, I was about to embark on a journey of unlearning. This begins on our bus route from downtown Bucharest where the group members were introduced to each other for the first time by describing what we were running away from. I didn’t realise that I was running away from anything.

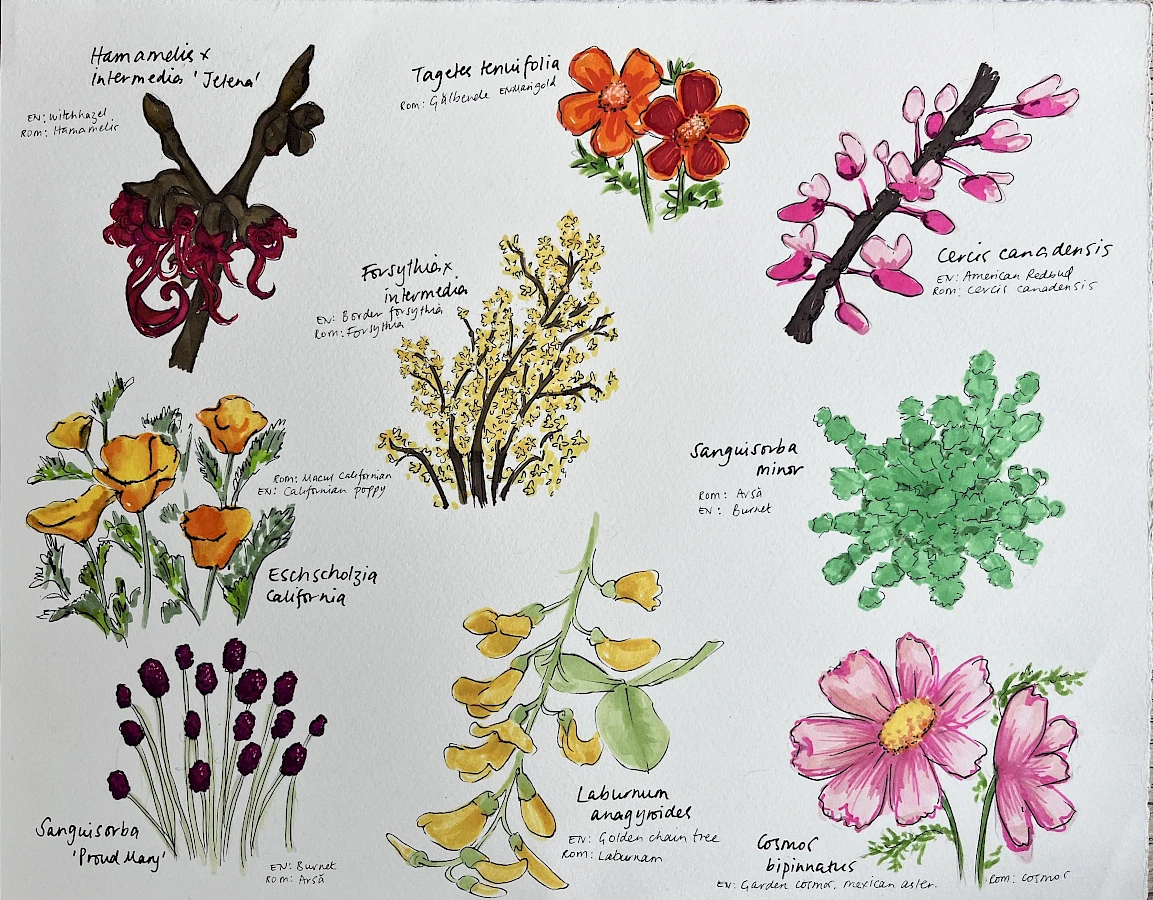

Inside the perimeter fence of the station stretches a long line of small trees and shrubs, each planted by a different artist. In their new outdoor home these living artworks have agency: they can grow and blossom and flower as they please. Some might not like the soil or light or heat and won’t flourish at all, others might go dormant and reappear next year, others may not. Some may enjoy their new freedom and rampage throughout the plot unchecked, causing hours more labour and intervention. Others still, with juicy new shoots, may succumb to the appetite of local wildlife: foxes, rabbits and deer. Word in the air might get out that the new hedge on the far perimeter is a welcoming habitat with plentiful bird feeders, and the densest bush will soon be filled with birdsong. As intermittent visitors to the station we witness these ongoing temporal changes from early winter 2023 to late spring 2024. The hard labour takes place in our absence: non-living artworks are installed as well as a cooking station, a compost toilet and a phyto-filtration system. Plans are being drawn up for a two-storey living space. Regular visitors to the station activate the space and bring new iterations and ideas.

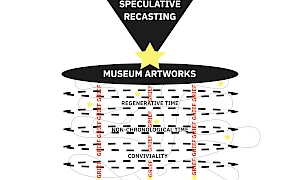

Artworks in standard modern art collections around the world are rarely given the same treatment. We discussed this in our March meeting with curator Charles Esche, who was visiting from Eindhoven. He spoke about his role in the reinvention of the Van Abbemuseum by what he calls demodernising the art collection through decolonial thinking. The ubiquitous white cube is designed to exclude so much. As soon as an artwork is installed, its former life is extinguished, like a butterfly succumbing to chloroform. The context for its existence is often erased with as little evidence as possible of its former life, thus enabling its new position in an aesthetic vacuum. This vacuum is fairly exclusive, as Esche explains, and inhospitable to people who do not easily fit into its criteria. His vision for a demodern art collection is in ‘reconnecting it to people and histories that it has excluded for too long.’1

This brings to mind Grace Ndiritu, the British/Kenyan artist who goes further with this line of thinking by reflecting on the mental state of artworks. In her work ‘Healing the Museum’ she talks about the responsibility of museums to look after the welfare of the museum objects, some of whom, in her view, are unhappy and were never meant to be seen by a ‘single ray of sunlight or looked at by millions of keen museum-goers. Hence, they feel like they are being robbed of their agency, with no rights of their own. As such, they want to be free.’2

Of the Kaiget Totem Poles in the Musée du quai Branly in Paris Ndiritu says: ‘They want to stand tall outside, feeling the sun on their surfaces, allowing rain to penetrate them and to fulfil the purpose for which they were created; they want their lives and their souls back.’3 Like Esche, she believes a powerful change can happen in our awareness of art objects and our relationships with them.

The group is returning to Siliștea Snagovului this week. It will be our last visit. For me there is a sense that the linear arrow of time – launched from the deep past, hovering momentarily here in the present before hurtling headlong to the future – has hesitated, like the fluctuating oscillations of a broken grandfather clock. Whilst contemplating the happenings and provocations on this small plot of land, the arrow is perhaps in flux and drawn to change its course, maybe to turn back on itself, or loop the loop in a continuous cycle, inviting us to think about the rhythmic pendulum of circular time and its interconnectedness with nature as an alternative way of being, and asking us ultimately to unlearn and consider a different perspective.

Related activities

-

–tranzit.ro

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

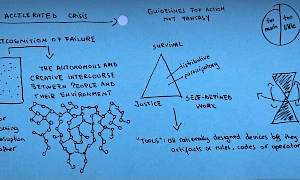

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

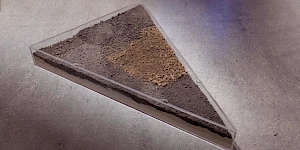

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production

The Studies Center of Museo Reina Sofía will publish an open call for four residencies of artistic practice for projects that address the emergencies and challenges derived from the climate crisis such as food sovereignty, architecture and sustainability, communal practices, diasporas and exiles or ecological and political sustainability, among others.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

–M HKA

The Lives of Animals

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at M HKA that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ is a series of sound installations by Özcan Ertek, Fulya Uçanok, Ömer Sarıgedik, Zeynep Ayşe Hatipoğlu, and Passepartout Duo, presented at Salt in Istanbul.

-

–SALT

Sound of Green

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ at Salt in Istanbul begins on 5 June, World Environment Day, with Özcan Ertek’s installation ‘Sound of Green’.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Open Call: Research Residencies

The Centro de Estudios of Museo Reina Sofía releases its open call for research residencies as part of the climate thread within the Museum of the Commons programme.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

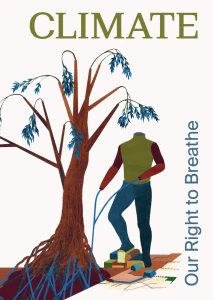

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organisations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

–SALT

The Lives of Animals, Salt Beyoğlu

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at Salt that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Plant(ing) Entanglements

The series of sound installations Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them ends with Fulya Uçanok’s sound installation Plant(ing) Entanglements.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production. Research Residencies

The projects selected in the first call of the Sustainable Art Practice research residencies are A hores d'ara. Experiences and memory of the defense of the Huerta valenciana through its archive by the group of researchers Anaïs Florin, Natalia Castellano and Alba Herrero; and Fundamental Errors by the filmmaker and architect Mauricio Freyre.

Related contributions and publications

-

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana Kuntranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftClimatetranzit.ro -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloThe Soils ProjectClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoThe Climate ForumClimateHDK-ValandEN es -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin Pogačar... and the Earth alongClimatePast in the Present -

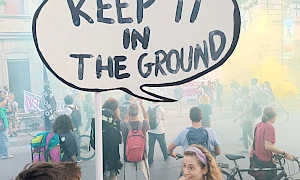

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Pollution as a Weapon of War

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimate -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

ClimateThe Climate Forum -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosThe Climate ForumClimate -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifThe Climate ForumClimate -

Pollution as a Weapon of War – a conversation with Svitlana Matviyenko

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Françoise Vergès – Breathing: A Revolutionary Act

Françoise VergèsClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Ana Teixeira Pinto – Fire and Fuel: Energy and Chronopolitical Allegory

Ana Teixeira PintoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Watery Histories – a conversation between artists Katarina Pirak Sikku and Léuli Eshrāghi

Léuli Eshrāghi, Katarina Pirak SikkuClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

The Veil of Peace

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuPast in the Presenttranzit.ro -

Indra's Web

Vandana Singh... and the Earth alongPast in the PresentClimateZRC SAZU -

One Day, Freedom Will Be

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoTowards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyInstitute of Radical ImaginationClimate -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoInstitute of Radical ImaginationClimate -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: The Arrow of Time

Catherine MorlandClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoInstitute of Radical ImaginationClimate -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoInstitute of Radical ImaginationClimate -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterThe Climate ForumClimatePast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nkule Mabaso, Nick AikensThe Climate ForumClimateHDK-Valand -

Eating clay is not an eating disorder

Zayaan KhanThe Climate ForumRecette. Reset. Recipes in and Beyond the InstitutionClimatePast in the Present -

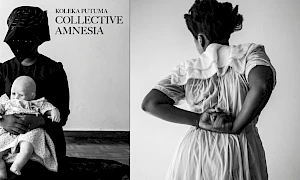

Graduation

Koleka PutumaThe Climate ForumClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaThe Climate ForumClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideThe Climate ForumClimate -

Soils

The Soils ProjectClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoThe Climate ForumClimate -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanTowards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the PresentClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezThe Climate ForumClimate -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna Zielińska... and the Earth alongClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia Golovko... and the Earth alongClimate