The Sun: Overexposure and Underexposure

The sun hits hard at 38°C when I visit Claudina’s farm in Coyaima, south of Tolima, Colombia, on 29 February 2020. She gives me a letter that solicits money for the building of ten new wells for the community, asking me to deliver it to an organization that supports small farmers. Claudina Loaiza is one of the first seed guardians I got in touch with through Grupo Semillas,1 inviting her to lead a meeting on the relationship between creole seed conservation and land recuperation in her territory. Another seed guardian I spoke with was Mercy Vera, who had traveled with Samanta Arango Orozco from Grupo Semillas to attend a convention of women farmers and ecological feminists in the summer of 2019.2

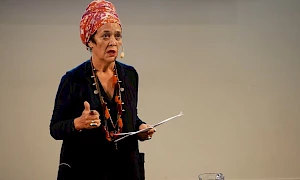

Marwa Arsanios, still from Who Is Afraid of Ideology? Part IV – Reverse Shot, 2022. Image courtesy of the artist.

After our meetings, we came to understand that being a seed guardian was a threat to armed forces in the region from all sides—whether the paramilitaries, dismantled guerrilla units, governmental forces, or the so-called private security companies enlisted to protect agribusiness. Mercy wept while talking about the moment of the limpieza [the cleansing], when the paramilitaries had lists of people to eliminate, in a purge of farmers and Indigenous people. Seed guardians, social leaders, and organizers are still, at present, considered a threat, and therefore a target. This, of course, was not the first purge that they or their ancestors had known about or lived through.

The creole seeds are beings with nonlegal status; the seed guardian is an undesired being with a legal status. She knows that the beings with nonlegal status are her only allies. In this desertic territory, there is a real water scarcity: the little water there is, is either sucked by the hydroelectric mechanism already in place or the one in the process of being built, then diverted through a government-built irrigation system to endless hectares of rice plantations. Under these conditions, the farmers have two choices: either to lease their lands to the plantations where they end up working for a very low wage, or to stubbornly stick with the land, if they can. Seed guardians have opted for the latter and have developed seeds that adapt to the desert climate. As Samanta says: This is revolutionary. In a way, the world order has forced Claudina and her community to wait for international funds and other humanitarian aid to assist their livelihood. In exchange for the historical and ongoing robbery of their land and resources, they are paid back the value of one or two wells for their survival. The letter Claudina gave me is still with me as I write, and I will soon give it to the friend who works at the organization. But this letter represents the tragedy and farce of history, its cruelty.

As we walk in the surroundings of Claudina’s farm, the sun is high. We try to take some landscape shots but the light is very strong, and our Panasonic camera doesn’t adapt to shifts in light so well. “We should have brought ND filters,” I tell Juma Hamdo. “And a reflector,” he responds. We stop at a spot to recall the murder of a seed guardian, and I notice that what is designated as the site of the crime cannot be captured fully by the camera lens. It’s not quite that the site cannot be framed in its totality, but that it seems somehow off-frame, or that something is lost inside the frame. Perhaps this is because one should not be able to capture this crime scene or perceive it as a particular place; or perhaps because the whole territory is a site of crime.

Blocking or inviting the sun too much would be the path to sight without seeing, or to seeing otherwise. The energy of the sun enables that path to sight. As McKenzie Wark writes in Molecular Red, the energy of labor and the elemental energy of nature are inseparable in the process of production and vitality.3 It is important to keep in mind that the inherent relation between labor and nature is the basis for the dynamic of production fed by the energy of the sun. The labor of seeing entails a relation between human labor and sunlight; the labor of making something appear or disappear.

The Surplus of Sight

The world economy we function within has opened up a space of sight and vision that allows at once for too much and too little seeing. In the same way that the crisis of capital lies in a surplus of production rather than in underproduction, we could say that the crisis (of sight) is in the surplus of the production of images—in the accumulation of images that end up unseen because they are too much seen. The intervention of the light—the sun—in combination with unsophisticated technology, produces images that are either too dark or too bright. The images I took refused to represent the crime scene with any accuracy, because the site exceeds the scene, and because, among an excess of information, we stopped being able to see it. The site mistrusts this surplus of production, and resists it.

Why does one need to capture a perfect representation of the crime scene if one knows that it exists? Photographic evidence that could have been taken to court might have helped, but the juridical fight is lost most of the time. It seems there is a need for another fight: another sight, or another labor of seeing.

In the darkroom where one develops photographic images, losing full vision is a necessary step in order to be able to see the images that appear on the negative after the acidification process. In order to see, one needs to go into the dark room. It almost sounds like a Christian theological path, which encourages you to walk through darkness in order to see the light of God, but it is a scientific process of image development. Indeed, the path of Christianity and the pursuit of scientific seeing have a faith in being “enlightened” in common.

In my early teenage years, I attended a Jesuit Catholic college not far from Beirut, my hometown. One day when I was in fifth grade, I saw many students standing in line in the headmistress’s office, taking turns to look at a piece of paper. Curious, I joined them in the office to discover that the paper featured a photocopied print of some woman saint, perhaps the Virgin Mary herself. The students were waiting to sit on a chair, stare at the paper for one minute, then look back at the wall. The headmistress then asked them to make a wish. I could see their faces change the moment they looked at the wall, and when they stood up from the chair to let the next pupil sit down, their bodies and attitude also seemed altered. When my turn came, I took a long breath, and after staring at the paper for one minute, lifted my head swiftly to look at the wall to observe the shadow of the saint or the Virgin Mary appear before me. I was so amazed I forgot to make a wish before having to vacate the chair for the next classmate. I could still see her shadow as I stood up, until she eventually disappeared. It left me dazzled. The next day in biology class the professor announced in a sardonic tone that he had heard from students about the “apparition” of the Virgin Mary. It was merely an optical illusion, he stated, and the fallacy should be brought to an end. I felt slightly better for not having made a wish, and saw the disappointment on the faces of my peers. After class, this disillusionment opened up a long discussion on whether or not we believed.

Sight was part of the mechanisms involved in the colonization of land by the Christian missionaries. Pictures of saints, perhaps like that in my headmistress’s office, were held up to Indigenous peoples in order to try to subdue and convince them to give up their land and goods. The sight of the shadow of the Virgin Mary on the wall is part of the same tactics of conversion and awe practiced by the Church. Whether, for the rationalist non-believer, the sight is an optical illusion, or, for the believer, it is a true miracle, it requires a labor of seeing: staring long enough at the same spot. This puts into question the neoliberal politics of visibility and invisibility, or of recognition through being visible. Appearance and disappearance fall in different registers: of labor, of religion, of chemistry.

The labor of seeing becomes an intrinsic condition for believing, and subsequently, for the dispossession of lands via religious conversion. The labor of seeing becomes the ultimate tool for colonization, extraction, and accumulation.

Marwa Arsanios, still from Who Is Afraid of Ideology? Part III – Micro Resistencias, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist.

The Labor of Seeing; Reverse Shot

In Chantal Akerman’s documentary Sud (South, 1999), the inscription of a site of crime within a territory is striking. The film focuses on the murder of African American James Byrd Jr., who was dragged behind a truck in Jasper, Texas, by white supremacists. The final sequence consists of a slow reverse shot, as if we are moving backward in time through the traces of the crime scene. The surrounding landscape becomes painful in its beauty and cruelty. We see its distortion.

Akerman’s intention to inscribe the memory of this violent incident in the landscape is quite contrary to the prerogatives of investigative work. It is not about making sense or searching for evidence. Akerman knew too well, from her own Jewish family history, what genocide is; she knew too well that investigative legal or journalistic work does not in itself guarantee justice. She understood that a new way of seeing the landscape would be necessary, for us to perceive it in its utmost cruelty. The reverse shot imposes another labor of seeing, flips time, and reverses history, in order to see its ghosts.

How to film the land?

If the representation of land is a kind of property, how could one film it without owning it? Is the ownership of the image of representation of land a property inside a property? Property is contained in infinite squares, which begin from a legal system that turns unbounded nature into land and land into property. Infinite squares of property.

An image inside an image

A struggle inside a struggle

A letter inside a letter

How to Measure the Void?

The hole dug in the ground to access water—the well requested by Claudina in her letter—must be at least fifty meters deep. For that reason, it is very costly, as the labor of digging takes time and there are many obstacles on the way. Tons of earth must be removed and the labor of such removal costs 100,000 Colombian pesos per day. It will take at least ninety days to do so, if not more. The cost of digging the well will amount to 50,000,000 Colombian pesos. This is the cost of making a void. The false idea of emptiness, terra nullius, void, was the ultimate excuse for conquest and colonialism. A physical void for survival and an illusory void as the basis for speculation, accumulation, and conquest.

Peering into the void inside the earth that has been dug for the well is like staring into the dark; it is like losing sight in order to gain water; it is like staring at the saint’s picture only to see the shadow on the wall, or like entering the darkroom in order to later be able to see the photograph. The labor of digging is similar to the labor of seeing in that its outcome requires a kind of voiding—a faith in losing sight only to recuperate it.

If one thinks from the perspective of more-than-human matter and physics, the void becomes an energetic space. According to Newtonian physics, a void is an absence of matter, a space that has no properties or laws, which means that it has no energy. Karen Barad updates this science to claim that in quantum physics, a vacuum is where particles are created, therefore there is an inseparability between matter and void. The vacuum, she says, is not silence, it is speaking, murmuring. It is a space of constant energy formation, where new organizations of particles take shape; a space to watch and listen to closely.5

How to measure the land?

When you need to measure areas directly in the field, divide the tract of land into regular geometrical figures, such as triangles, rectangles, or trapeziums. Then take all the necessary measurements, and calculate the areas according to mathematical formulas.

Extension

She extends her body to perform care tasks for others and to maintain the land. The gestures of care that women perform every day to take responsibility for other people’s lives, other people’s mistakes, other people’s work. In order to conceal, or to expose. She extends herself, stretches herself to perform responsibility. Her body is a tool for others. Her body is a threat for others. Her body becomes an obstacle to the expansionists. She holds the world. Holding the world from below is threatening.

Mariam, my caregiver when I was a child, used to stockpile bread in the fridge and hide bags of rice and lentils in the cupboard, surveilling them closely to make sure supplies never became low. Having lived through the First World War, the locust infestation of 1915, and the deadly embargo on Mount Lebanon by Jamal Pasha (known as “the slaughterer”), she was forever afraid of running out of food. She transmitted the history of the Great Famine of Mount Lebanon to me and my siblings through the vivid images of her stories of her two dead brothers. One brother choked on a blade of barley grass when he tried to swallow it because of hunger, and the other was beaten on his forehead by the priest and the schoolteacher until he was dizzy and could no longer hear. “He came back home, went to sleep, and never woke up,” she recounted. We asked her again and again what happened to the priest and if he was held accountable; she always ignored our question or yelled at us saying that no one holds a priest accountable. Mariam understood there was an injustice; she knew life was unfair to her, as it had been to her brothers, but she accepted her lot—she was a woman, a secondary creature. Her brother died after beatings by a representative of God on Earth, and that was unjust, but no one holds a priest accountable. And the lives of the peasant families who were not given access to land was not fair either. As writer and researcher Wissam Saade recounts:

Land ownership would witness a total overhaul in the nineteenth century: the passage from the tax rental system to the recognition of the right of the soil’s hereditary appropriation. Families who exercised a certain role within the framework of the Ottoman tax renting system would then claim their appropriation rights as farmers.6

Mariam understood that the fact she couldn’t read or write had led her to work in people’s houses as a caregiver and cook. Despite all of this, she never stopped extending herself to others; it was her only way to survive, to make a living. Maintaining other people’s land when she worked in the olive groves before being sent to work in houses in the city, where she would take care of other people’s lives. In the 1986 economic crisis during the civil war, her money, her only possession, was devalued. After years of hard work, she again found herself powerless before her own family, from whom she had tried to run away.

Marwa Arsanios, still from Who Is Afraid of Ideology? Part IV – Reverse Shot, 2022. Image courtesy of the artist.

An image of her natal village reveals the history of its mountainous landscape in a reverse shot. The land is poor or infertile, as they say; not arid, but only good for a certain type of agriculture.

In the Lebanese mountains, there was an important consequence of the peasant revolution, even though the country was heading toward a mad mercantilism, and an increasingly pronounced social inequality. The peasants claimed that they were the ones who had established an intimate relationship with this land, an intimacy of proximity, of cultivation, and therefore that this land was part of their identity, their experience, their life in common.7

Despite this redistribution of land, Mariam did not have a right to inheritance because she was born a woman. Inheritance law in Lebanon clearly states that it is legal to disinherit a child, and this tended to be used against women to keep inheritance in the patriarchal bloodline. So, Mariam was disinherited, like many other women from her generation.

Who Works the Land?

What do you inherit when you inherit a piece of land? You inherit its trees, the trees’ olives, all the produce that grows on it. We inherit the soil: its microbiome of bacteria.

Inheritance is also a formation of different alchemical components that work to render value possible. The bacteria work together to maintain the life of the soil, the fertility of the land, and so its value.

Inheritance is chemical and alchemical. The void is not lawless, the void is a chemical and physical formation. The space without property is where particles form.

Now the only plausible history is a history of disinheritance. The free labor of the microbiome and bacterial formations that work the soil and help the land keep its fertile values. Disinherited beings are considered secondary. Even though recognized as citizens for the sake of control and reproduction, they are written out of any inheritance.

The emotional and affectual economy of debt that women inheritors have to carry is heavy. They should feel thankful not to have been disinherited. The law always threatens to disinherit them.

Disinheritance is not a defeat, disinheritance is a flood in the system. She inherits a flood or a drought. She is disinherited because of a flood. She inherits a flooded system.

What is inheritance outside of property laws? Or what is property when it is emptied of inheritance? Property appears and disappears through inheritance and disinheritance. Labor appears and disappears through liquidity. Liquidity evaporates with sun exposure and overexposure. Abstraction melts when liquidity ends. She inherits a sun that hits hard.

Marwa Arsanios, still from Who Is Afraid of Ideology? Part IV – Reverse Shot, 2022. Image courtesy of the artist.

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production

The Studies Center of Museo Reina Sofía will publish an open call for four residencies of artistic practice for projects that address the emergencies and challenges derived from the climate crisis such as food sovereignty, architecture and sustainability, communal practices, diasporas and exiles or ecological and political sustainability, among others.

-

–tranzit.ro

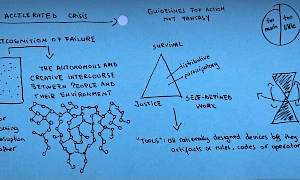

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

–M HKA

The Lives of Animals

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at M HKA that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ is a series of sound installations by Özcan Ertek, Fulya Uçanok, Ömer Sarıgedik, Zeynep Ayşe Hatipoğlu, and Passepartout Duo, presented at Salt in Istanbul.

-

–SALT

Sound of Green

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ at Salt in Istanbul begins on 5 June, World Environment Day, with Özcan Ertek’s installation ‘Sound of Green’.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Open Call: Research Residencies

The Centro de Estudios of Museo Reina Sofía releases its open call for research residencies as part of the climate thread within the Museum of the Commons programme.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organisations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

–SALT

The Lives of Animals, Salt Beyoğlu

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at Salt that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Plant(ing) Entanglements

The series of sound installations Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them ends with Fulya Uçanok’s sound installation Plant(ing) Entanglements.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production. Research Residencies

The projects selected in the first call of the Sustainable Art Practice research residencies are A hores d'ara. Experiences and memory of the defense of the Huerta valenciana through its archive by the group of researchers Anaïs Florin, Natalia Castellano and Alba Herrero; and Fundamental Errors by the filmmaker and architect Mauricio Freyre.

Related contributions and publications

-

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoThe Climate ForumClimateHDK-ValandEN es -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloThe Soils ProjectClimateVan Abbemuseum -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin Pogačar... and the Earth alongClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Pollution as a Weapon of War

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimate -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

ClimateThe Climate Forum -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosThe Climate ForumClimate -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifThe Climate ForumClimate -

Pollution as a Weapon of War – a conversation with Svitlana Matviyenko

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Françoise Vergès – Breathing: A Revolutionary Act

Françoise VergèsClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Ana Teixeira Pinto – Fire and Fuel: Energy and Chronopolitical Allegory

Ana Teixeira PintoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Watery Histories – a conversation between artists Katarina Pirak Sikku and Léuli Eshrāghi

Léuli Eshrāghi, Katarina Pirak SikkuClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Indra's Web

Vandana Singh... and the Earth alongPast in the PresentClimateZRC SAZU -

One Day, Freedom Will Be

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoTowards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyInstitute of Radical ImaginationClimate -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoInstitute of Radical ImaginationClimate -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: The Arrow of Time

Catherine MorlandClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoInstitute of Radical ImaginationClimate -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoInstitute of Radical ImaginationClimate -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterThe Climate ForumClimatePast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nkule Mabaso, Nick AikensThe Climate ForumClimateHDK-Valand -

Eating clay is not an eating disorder

Zayaan KhanThe Climate ForumRecette. Reset. Recipes in and Beyond the InstitutionClimatePast in the Present -

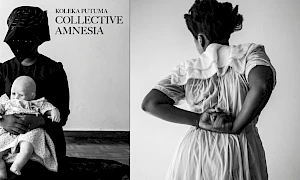

Graduation

Koleka PutumaThe Climate ForumClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaThe Climate ForumClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideThe Climate ForumClimate -

Soils

The Soils ProjectClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoThe Climate ForumClimate -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanTowards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the PresentClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezThe Climate ForumClimate -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna Zielińska... and the Earth alongClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia Golovko... and the Earth alongClimate