No Doubt It Is a Culture War

In this conversation, originally published in 2023 as part of Eurasia - An Atlas, artist Oleksiy Radinsky and curator Joanna Zielińska reflect on the term Eurasia and what it means in the context of Ukraine and Russia’s historical and ongoing imperialisms. At the same time Radinsky reflects on the role of culture in the context of of war, both for the opressor and opressed.

Joanna Zielińska: Where are you now?

Oleksiy Radinsky: I’m now in Kyiv.

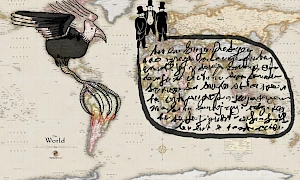

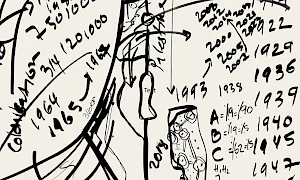

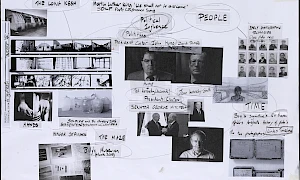

Oleksiy Radynski, Kyiv Film Stills, 2022. Courtesy the artist

JZ: Can you describe your background?

OR: I’m a filmmaker and writer. I mostly work with the documentary form. My background is in film theory. I graduated from the Cultural Studies department at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy which at the time (the first decade of this century) had been a very special place to study, as it was combining the interdisciplinary approaches of dissident humanities of the late-Soviet era with the Western theory that arrived in our academia like an avalanche during the 1990s, after decades of being banned. In 2008, together with fellow students and young faculty of our department, we founded a collective called Visual Culture Research Center (VCRC). We were interested in interdisciplinary action between the fields of research-based art, grassroots activism and experimental knowledge production. These were the years of decline of the Center for Contemporary Art founded by George Soros in Kyiv and hosted in our academy, which has been growing increasingly conservative and nationalist, and was striving to get rid of any kind of contemporary art within its walls. Our collective shared a space with the CCA until the academy kicked it out. After that, we were able to sustain a programme of exhibitions, seminars and debates in the same premises for a couple of more years, until VCRC were kicked out of the academy as well. Since then, VCRC has been functioning as an autonomous, nomadic para-institution. In the meantime, I had quit the PhD programme in film theory at Kyiv-Mohyla Academy to focus on my own film practice.

Oleksiy Radynski, Kyiv Film Stills, 2022. Courtesy the artist

The turning point for my practice as a filmmaker came during the Maidan uprising in Kyiv, which has been an important part of the take-the-square movements during the 2011–14 global cycle of struggle. It’s interesting that the uprising at Maidan was nearly the only one of those movements that managed to achieve its goals (to oust the authoritarian government and prevent the recolonisation of the Ukrainian state by Russia). However, the Maidan has been nearly totally erased from the global history of these struggles, which are most often associated with Tahrir, Occupy Wall Street and Indignados. This is of course due to a successful disinformation campaign by Russia, as well as the fact that it managed to start a counter-revolutionary war in Ukraine to do away with the Maidan event which could lead to a domino effect in Russia and other regional autocracies.

During the Maidan uprising, me and my film team had been documenting the development at the occupied central square in Kyiv for over three months, in-depth, in the form of engaged anthropological observation. After the fall of the regime and the victory of Maidan, we went to Crimea to film the start of counter-revolution in the form of the Russian military takeover of the peninsula, and then to the Donbas region where the anti-Maidan counterrevolution had only just started taking the most violent form. We’d been working in the mode of counter-information, immediately editing and publishing our footage online. Later on, we developed this into a film duology dealing with the Maidan uprising (Integration, 2015) and the subsequent counter-revolution (People Who Came to Power, co-directed with Tomas Rafa, 2016). In the following years, I’ve focused more on research-oriented documentary practice.

Oleksiy Radynski, Kyiv Film Stills, 2022. Courtesy the artist

JZ: How would you describe the political climate in Ukraine between the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the beginning of the war in 2022? How would you connect these political moments in history?

OR: I would prefer to speak of the political climate in Europe (or ‘Eurasia’, if you will – in the sense of this term that I’m describing in my next answer), and the political climate in Ukraine as a part of it. Climate in any sense (be it planetary climate or ‘political climate’) cannot be confined to one given country. I would describe this climate on the continent as an attempt to do business as usual – whatever it takes – while ignoring the impending disaster. This refers both to the attempts to do business as usual with the Russian Federation (despite the cosmetic sanctions introduced after the annexation of Crimea), as well as the tendency to do business as usual with regards to the planetary climatic disaster that we’re all facing. And these two tendencies are very closely connected, since everyone knows that in order to prevent planetary catastrophe, humanity needs to stop burning fossil fuels – while our continued dependence on fossil fuels is a backbone of Putinism. In that sense, survival of humanity on planet Earth and the survival of the Russian ruling regime are two conflicting things at odds with each other and they can’t really be reconciled. After 2014, Europe had a chance to wake up to both the military and climatic catastrophes that were impending, but it chose to ignore both of them. As late as 2015, Germany had signed the contract with the Russian Federation to build Nord Stream 2, a gas pipeline that would not only lock in the European continent in its attachment to Russian fossil fuels, but would also render obsolete the geopolitical raison d’être of the Ukrainian state, which had unfortunately been reduced to the status of the transit zone transporting Siberian fossil fuels to Western Europe. The moment the deal to build Nord Stream 2 had been signed by the Germans, the stage for the all-out Russian invasion of Ukraine had been set.

JZ: What would be your understanding of the concept of Eurasia that has various, sometimes very extreme interpretations? Some understand it as a supercontinent with complex political, economic and cultural relationships, an example of diversity reflecting the dynamic processes of modernisation and multipolarity. For others, it is an illustration of a certain ideology and imperialist ambitions. For the East and for the West, Eurasia means something completely different. There is also increasing discussion of regionalisation, and the importance of locality.

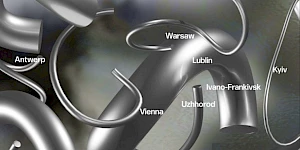

OR: I would describe Eurasia as a space where transcontinental infrastructure for the extraction and consumption of fossil fuels operates: a space between the unceded lands of the Indigenous in the Siberian tundra where oil and gas are extracted, and the European factories and homes where it is emitted into the atmosphere. Eurasia is a span of the Friendship oil pipeline, it’s a span of Nord Stream gas pipeline. These pipelines are not just connecting the different parts of the continent, they are creating a financial and political symbiosis between Russian autocracy and European liberal democracy. Eurasia is a space of complicity: it’s a space that has made it possible for the German taxpayers to become the single biggest sponsors of Russia’s fascist war in Ukraine, simply by paying their gas bills.

The only use of the concept of ‘Eurasia’ that is relevant for us in Ukraine is, unfortunately, its appropriation by the Russian far right ideology of ‘Eurasianism’. It’s been developed by fascist thinkers such as Alexander Dugin and has become an official ideological doctrine in the Russian Federation. This is exemplified for instance in the foundation of Eurasian Economic Union, a new tool of Russian imperialism that tries to regain control over its former colonies in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, which it had lost during the two previous waves of disintegration of the Russian Empire (that is, after 1917 and 1991).

Oleksiy Radynski, Kyiv Film Stills, 2022. Courtesy the artist

Eurasianism is an extremely obscurantist, anti-Western, anti-liberal and in some cases openly fascist ideology whose main point is to prove that Russia somehow belongs to a different kind of civilisation that has nothing to do with the West. In that sense, it’s a pure form of deceit, an ideological manipulation that’s trying to cover the void at the core of its argument, or indeed a void in the place of this obscure idea of a ‘mysterious Russian soul’ or ‘great Russian culture’ still cherished in the West. In reality, there is nothing non-Western about the Russian state, its history and its development. Of course, I’m not speaking here about the ‘West’ as a set of values, or in a qualitative sense. I’m speaking about the West strictly in the sense of white colonial expansion in the modern era. This expansion of white settlers from Europe has been directed not only westwards, to the Americas and other continents, but also eastwards, towards the Eurasian lands that now comprise the Russian Federation but that belonged to largely Turkic and Ugro-Finnic peoples. A lot of them were exterminated in genocides that were so brutal that very little knowledge about those events themselves has even survived.

For some time now, there’s been a reckoning going on for the westward expansion of white Europeans. Now it's high time to reckon for their eastward expansion as well, which would expose and question the settler colonial nature of the Russian state itself. The Russian Eurasianists are simply trying to obscure this essentially Western colonial nature of their state in their absurd attempts to distance themselves from the West.

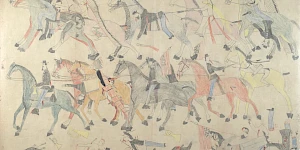

If there’s any chance to reclaim the concept of Eurasia from the Russian fascists, this can only come through decolonial thought and action. Eurasia is a very homogenising term that is used to describe wildly different cultures that still exist in the territory of the Russian Federation. Instead of talking about Eurasia in general, I would rather talk about the Bashkirs, the Buryats, the Kalmyks, the Khanty, the Komi, the Mari, the Nentsy, the Tatars, the Udmurts, the Yakuts and many many others – all of those peoples that are still oppressed under the Russian colonial rule.

Oleksiy Radynski, Kyiv Film Stills, 2022. Courtesy the artist

JZ: You are right in saying that the term Eurasia has been completely ideologised in recent decades. However, it is important to take a broader historical perspective that definitely goes beyond Russian territory and a Russian definition of Eurasianism. This term was also used by some artists like Joseph Beuys and Jimmy Durham and Nam June Paik to describe plurality of cultures. That is why the decolonisation discourse you are talking about, which will revise these concepts, is so important now. How do you see the process of decolonisation of the East in this context? This concept wasn't popular enough. What is the future?

OR: You are right that the application of decolonial optics to Eastern Europe and Russia hasn’t really been happening in the Western discourse until very recently. I think that one of the reasons for this is that decolonial thinking remains quite Eurocentric itself, in the sense that it’s focused on critiquing and countering those forms of colonialism that characterised the westward expansion of white Europeans. This was largely the colonialism of maritime empires that colonised distant lands. But this is not the only form that this white expansion had. As a result, it’s sometimes hard to grasp that not every form of colonialism entails the existence of an ocean between the metropole and the colony. And it’s somehow hard to grasp that the coloniser and the colonised can be of the same skin colour – which is exactly what was happening in Eurasia.

What you refer to as the decolonisation of the East can actually be worded differently: the decomposition of the Russian Federation and the emergence of the liberated republics in its territory. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is just the last sign of an internal conflict that’s ripping apart this pseudo-Federation, which is in fact a highly centralised empire based on racist and extractivist governance by Moscow and Saint Petersburg. The end to this war does not lie in Ukraine but in the Russian Federation itself, just as the cause of this war is inside Russia itself. There will be no real end to this war until the Russian empire ceases to exist in its current form. And I’m really surprised that this sounds so far-fetched and totally unrealistic for the Western audience. Everyone is so quick to forget the fact that in the course of the last century, there were already two phases of the collapse of this empire: one after the October Revolution, and the other with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 (which, in fact, was also seen as something totally impossible, and even undesirable, by the Western powers including the White House – just as the dissolution of the Russian Federation is seen now by many). What we’re witnessing now is the third phase of this collapse.

Oleksiy Radynski, Kyiv Film Stills, 2022. Courtesy the artist

JZ: What is the role of culture and artists in the context of war? As we know, Russia attacks not only civilian targets, but also cultural sites and monuments that represent the strength and national identity of Ukraine. In my opinion, this reminds us of the importance of culture in sustaining the spirit of a nation and beyond.

OR: I would like to answer that in a two-fold way, since at every war culture is enacted by both sides of the hostilities: that of the aggressor and that of the object of the aggression. As I’m located on a latter side, things are quite simple for me and a lot of my colleagues: since 24 February 2022, we have a feeling that our work has just become much more relevant than it ever was, and our greatest privilege is to be able to continue our work that contributes to anti-fascist, anti-colonial and anti-imperialist effort. I’m speaking of course primarily of critical artists and the representatives of the socially engaged art scene.

What I find much more interesting is the role of the culture of the aggressor. There’s been a lot of talk recently about the role of Russian culture in the descent of the Russian Federation into an openly fascist monster. There’s no doubt for me that the Russian cultural and artistic scenes are totally complicit with this disaster. This includes the so-called ‘politicised’ segments or Russian contemporary art that had been so cherished in the West despite their total political irrelevance at home. This also includes Western-style mega-institutions which had been simply used as a fig leaf to normalise fascist dictatorship (see Putin’s visit to the opening of V-A-C museum in Moscow just a couple of months before the invasion). However, I think that simply boycotting Russian culture is a step that, however necessary, is not enough. What’s actually needed is a thorough and critical deconstruction of Russian culture as a colonial and imperial construct. This includes the myth of the ‘great Russian culture’ as it circulates in the Western academia and art circles. It should become clear that this myth of ‘greatness’ – that has nothing to do with the actual merits of Russian writers, artists and philosophers – has provided ground for the ideology of Russian supremacy that gave us this war. This is a war that’s grounded on flawed cultural and historical concepts (such as ‘the Russian world’, ‘the great Russian culture’ and so on) and in that sense this is without a doubt a culture war.

Oleksiy Radynski, Kyiv Film Stills, 2022. Courtesy the artist

Related activities

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–VCRC

Kyiv Biennial 2023

L’Internationale Confederation is a proud partner of this year’s edition of Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Where are the Oases?

PEI OBERT seminar

with Kader Attia, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Emily Jacir, Achille Mbembe, Sarah Nuttall and Françoise VergèsAn oasis is the potential for life in an adverse environment.

-

MACBA

Anti-imperialism in the 20th century and anti-imperialism today: similarities and differences

PEI OBERT seminar

Lecture by Ramón GrosfoguelIn 1956, countries that were fighting colonialism by freeing themselves from both capitalism and communism dreamed of a third path, one that did not align with or bend to the politics dictated by Washington or Moscow. They held their first conference in Bandung, Indonesia.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

Maria Lugones Decolonial Summer School

Recalling Earth: Decoloniality and Demodernity

Course Directors: Prof. Walter Mignolo & Dr. Rolando VázquezRecalling Earth and learning worlds and worlds-making will be the topic of chapter 14th of the María Lugones Summer School that will take place at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Archive of the Conceptual Art of Odesa in the 1980s

The research project turns to the beginning of 1980s, when conceptual art circle emerged in Odesa, Ukraine. Artists worked independently and in collaborations creating the first examples of performances, paradoxical objects and drawings.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school is organised by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in partnership with ZRC SAZU (the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts) as part of the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–MACBA

Song for Many Movements: Scenes of Collective Creation

An ephemeral experiment in which the ground floor of MACBA becomes a stage for encounters, conversations and shared listening.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

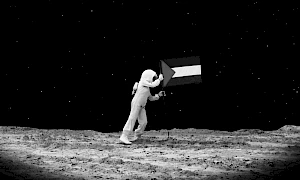

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

HDK-Valand

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Gothenburg

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and Mills Dray (HDK-Valand), 17h00, Glashuset

-

Moderna galerija

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Ljubljana

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Bojana Piškur (MG+MSUM) and Martin Pogačar (ZRC SAZU)

-

WIELS

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Subversive Film and Alex Reynolds, 19h00, Wiels Auditorium

-

–

Kyiv Biennial 2025

L’Internationale Confederation is proud to co-organise this years’ edition of the Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica

Curated by MACBA director Elvira Dyangani Ose, along with Antawan Byrd, Adom Getachew and Matthew S. Witkovsky, Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica is the first major international exhibition to examine the cultural manifestations of Pan-Africanism from the 1920s to the present.

-

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

NCAD

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Dublin

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and members of the L'Internationale Online editorial board: Maria Berríos, Sheena Barrett, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Sofia Dati, Sabel Gavaldon, Jasna Jaksic, Cathryn Klasto, Magda Lipska, Declan Long, Francisco Mateo Martínez Cabeza de Vaca, Bojana Piškur, Tove Posselt, Anne-Claire Schmitz, Ezgi Yurteri, Martin Pogacar, and Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, 18h00, Harry Clark Lecture Theatre, NCAD

-

–

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

WIELS

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels. Rana Issa and Shayma Nader

Join us at WIELS for an evening of fiction and poetry as part of L'Internationale Online's 'Collective Study in Times of Emergency' publishing series and public programmes. The series was launched in November 2023 in the wake of the onset of the genocide in Palestine and as a means to process its implications for the cultural sphere beyond the singular statement or utterance.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Study Group: Aesthetics of Peace and Desertion Tactics

In a present marked by rearmament, war, genocide, and the collapse of the social contract, this study group aims to equip itself with tools to, on one hand, map genealogies and aesthetics of peace – within and beyond the Spanish context – and, on the other, analyze strategies of pacification that have served to neutralize the critical power of peace struggles.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Near East, Far West. Kyiv Biennial 2025

The main exhibition of the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, titled Near East, Far West, is organized by a consortium of curators from L’Internationale. It features seven new artists’ commissions, alongside works from the collections of member institutions of L’Internationale and a number of other loans.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: The Brighter Nations in Solidarity: Even in the Midst of a Genocide, a New World Is Being Born

PEI Obert presents a lecture by Vijay Prashad. The Colonial West is in decay, losing its economic grip on the world and its control over our minds. The birth of a new world is neither clear nor easy. This talk envisions that horizon, forged through the solidarity of past and present anticolonial struggles, and heralds its inevitable arrival.

-

–M HKA

Homelands and Hinterlands. Kyiv Biennial 2025

Following the trans-national format of the 2023 edition, the Kyiv Biennial 2025 will again take place in multiple locations across Europe. Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA) presents a stand-alone exhibition that acts also as an extension of the main biennial exhibition held at the newly-opened Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN).

In reckoning with the injustices and atrocities committed by the imperialisms of today, Kyiv Biennial 2025 reflects with historical consciousness on failed solidarities and internationalisms. It does this across an axis that the curators describe as Middle-East-Europe, a term encompassing Central Eastern Europe, the former-Soviet East and the Middle East.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Bodies of Evidence. A lecture by Ido Nahari and Adam Broomberg

In the second day of Open PEI, writer and researcher Ido Nahari and artist, activist and educator Adam Broomberg bring us Bodies of Evidence, a lecture that analyses the circulation and functioning of violent images of past and present genocides. The debate revolves around the new fundamentalist grammar created for this documentation.

-

–

Everything for Everybody. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Everything for Everybody’ takes place in the Ukraine, at the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture.

-

–

In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture’ takes place at the Dovzhenko Centre in Kyiv.

-

MACBA

School of Common Knowledge: Fred Moten

Fred Moten gives the lecture Some Prœposicions (On, To, For, Against, Towards, Around, Above, Below, Before, Beyond): the Work of Art. As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA presents this lecture on artworks and art institutions in relation to the challenge of blackness in the present day.

-

–MACBA

Visions of Panafrica. Film programme

Visions of Panafrica is a film series that builds on the themes explored in the exhibition Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, bringing them to life through the medium of film. A cinema without a geographical centre that reaffirms the cultural and political relevance of Pan-Africanism.

-

MACBA

Farah Saleh. Balfour Reparations (2025–2045)

As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA is co-organising Balfour Reparations (2025–2045), a piece by Palestinian choreographer Farah Saleh included in Hacer Historia(s) VI (Making History(ies) VI), in collaboration with La Poderosa. This performance draws on archives, memories and future imaginaries in order to rethink the British colonial legacy in Palestine, raising questions about reparation, justice and historical responsibility.

-

MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica OPENING EVENT

A conversation between Antawan I. Byrd, Adom Getachew, Matthew S. Witkovsky and Elvira Dyangani Ose. To mark the opening of Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, the curatorial team will delve into the exhibition’s main themes with the aim of exploring some of its most relevant aspects and sharing their research processes with the public.

-

MACBA

Palestine Cinema Days 2025: Al-makhdu’un (1972)

Since 2023, MACBA has been part of an international initiative in solidarity with the Palestine Cinema Days film festival, which cannot be held in Ramallah due to the ongoing genocide in Palestinian territory. During the first days of November, organizations from around the world have agreed to coordinate free screenings of a selection of films from the festival. MACBA will be screening the film Al-makhdu’un (The Dupes) from 1972.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Cinema Commons #1: On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes

On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes is a Museo Reina Sofía film programme overseen by Miriam Martín and Ana Useros, and the first within the project The Cinema and Sound Commons. The activity includes a lecture and two films screened twice in two different sessions: John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948) and John Gianvito’s The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (2001).

-

–

Vertical Horizon. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Vertical Horizon’ takes place at the Lentos Kunstmuseum in Linz, at the initiative of tranzit.at.

-

–

International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People: Activities

To mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People and in conjunction with our collective text, we, the cultural workers of L'Internationale have compiled a list of programmes, actions and marches taking place accross Europe. Below you will find programmes organized by partner institutions as well as activities initaited by unions and grass roots organisations which we will be joining.

This is a live document and will be updated regularly.

-

–SALT

Screening: A Bunch of Questions with No Answers

This screening is part of a series of programs and actions taking place across L’Internationale partners to mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People.

A Bunch of Questions with No Answers (2025)

Alex Reynolds, Robert Ochshorn

23 hours 10 minutes

English; Turkish subtitles -

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Until Liberation: A Collective Reading and Listening Session by Learning Palestine

PEI Obert presents a collective session with Learning Palestine. At this historical juncture – amid the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the censorship and repression of all things Palestinian – Learning Palestine invites us to gather not only in refusal but also in affirmation.

Related contributions and publications

-

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

The Kitchen, an Introduction to Subversive Film with Nick Aikens, Reem Shilleh and Mohanad Yaqubi

Nick Aikens, Subversive FilmSonic and Cinema CommonslumbungPast in the PresentVan Abbemuseum -

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Rewinding Internationalism

InternationalismsVan Abbemuseum -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Veil of Peace

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuPast in the Presenttranzit.ro -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Everything will stay the same if we don’t speak up

L’Internationale ConfederationEN caInternationalismsStatements and editorials -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Rethinking Comradeship from a Feminist Position

Leonida KovačSchoolsInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Reading list - Summer School: Our Many Easts

Summer School - Our Many EastsSchoolsPast in the PresentModerna galerija -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Dispatch: ‘I don't believe in revolution, but sometimes I get in the spirit.’

Megan HoetgerSchoolsPast in the Present -

Dispatch: Notes on (de)growth from the fragments of Yugoslavia's former alliances

Ava ZevopSchoolsPast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

Broadcast: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency (for 24 hrs/Palestine)

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board, Rana Issa, L’Internationale Confederation, Vijay PrashadInternationalismsSonic and Cinema Commons -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Present Present Present. On grounding the Mediateca and Sonotera spaces in Malafo, Guinea-Bissau

Filipa CésarSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the Present -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

S come Silenzio

Maddalena FragnitoEN itInternationalismsSituated Organizations -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cinq pierres. Une suite de contes

Shayma Nader–EN nl frInternationalisms -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Speaking in Times of Genocide: Censorship, ‘social cohesion’ and the case of Khaled Sabsabi

Alissar SeylaInternationalisms -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Today, again, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalisms -

Isabella Hammad’ın icatları

Hazal ÖzvarışEN trInternationalisms -

To imagine a century on from the Nakba

Behçet ÇelikEN trInternationalisms -

Internationalisms: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardInternationalisms -

Dispatch: Institutional Critique in the Blurst of Times – On Refusal, Aesthetic Flattening, and the Politics of Looking Away

İrem GünaydınInternationalisms -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials