In November 2016 I met Walid Kowatlı in Gaziantep in Turkey to see the rehearsals of a new performance he has been preparing with artists living in the city from Syria. Kowatlı is a theatre and cinema director from Damascus in Syria, who studied in Sofia in Bulgaria in the 1970s, and lived in Sofia and Damascus for a large part of his life. He started living and working between Gaziantep and Dubai after the Syrian Revolution began in 2011. We talked about this performance and his recent films about children in the refugee camps in Turkey, which depict hope and future in relation to the Revolution, besides destruction and trauma. This text is not about my conversation with Kowatlı or the performance in particular, but certainly some of his words from war to trauma, from hope to future, from human rights to democracy, and the mobility of people and artefacts have inspired its direction.

Talking about the last attacks on the M10 hospital in Aleppo, Walid Kowatlı mentioned the increasing violence in the war over the last months. People are left without water, hospitals are bombed. This raises urgent questions as to where the threshold to intervene will be. As Ban Ki-moon compared the M10 to a slaughterhouse on the night of the incident, Dr. Sahloul, one of the volunteers of the hospital, gave a striking response: "This is a new normal that is created in this conflict that the international community is tolerating. Besides the descriptions of what is happening, and the words of condolences, we are not seeing any action to stop this."1 In addition to its direct meaning, this statement basically suggested the further potential increase of violence in Syria in future. Obviously, Walid Kowatlı and Dr. Sahloul were referring to the Assad regime and inviting international representation to intervene to stop the war. As we keep watching the violence of the war in Syria or the ISIS terrorist attacks in the media, I came to think that our tolerance for (seeing) violence has been increasing as well, and this is influencing the fear for ourselves. A fear that the same might happen to us, to our loved ones, that we might face the same violence one day so we should shut up against our autocratic governments, or we might have to leave our houses one day, we might have to flee...

The fear of uncertainty is one of the elements we share in the infrastructure of trauma and pain, but then we react differently. Zygmunt Bauman (2006) describes it as the "liquid condition", not knowing what we can rely on or invest our hopes and expectations in, or not feeling secure and free, which, according to him, might be an explanation for the psychology behind the rise in nationalism and conservative politics. Jacques Derrida explains this fear as the trauma for what the near or far future might be holding for us. For refugees (in camps): "Yet, the schema of trauma must be complicated, questioned in its 'chronoIogy' – that is, the thought and order of temporalization the term seems to imply. For the wound remains open because of terror of the future and not only the past. The ordeal of the event has as its tragic correlate not what is presently happening or what has happened in the past but the trauma to be produced by the future, by the to come, by the threat of the worst to come, rather than by an aggression that is 'over and done with'" (Borradori 2003). The opening line of Walid Kowatlı's new performance is a warning amongst refugees: "Do not pay the smuggler before he brings you to the other side".

I was in the camps around Zagreb, Dunkirk, and Lesbos for research this summer; refugees were held for an indeterminate amount of time, to be sent to Turkey. The agreement on the exchange of Syrian refugees between the European Union and Turkey, signed on 20 March 2016, has effectively altered the physical borders of Greece, by excising some of the Greek islands in the Aegean Sea from Greece, making them into black holes. All refugees, "aliens", arriving on these Greek islands, or intercepted in the waters around them, are denied access to the mainland for the asylum application process, treated with mandatory detention, and, in time, sent to Turkey. This agreement breaches constitutions and the United Nations human rights and asylum conventions. It is deemed that refugees are a threat to the security of nations and that therefore they should be imprisoned, but they are still part of humanitarian discourses. However, several organisations that work with refugees, including the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and Doctors Without Borders (MSF), have already withdrawn from being involved in the management of these newly defined deportation camps.

Due to this agreement, Lesbos is becoming an offshore island which reminds us of the Australian government's Pacific Solution in terms of its consequences. But, onshore "islands" have also been emerging, for instance in Idomeni, Grande Synthe and Calais, where the (national or international) law does not protect the asylum seeker. People in the formal or informal camps are not even allowed to apply for asylum, so there is no exact reckoning of numbers and names. Following investigations regarding the new formal camp that opened next to the Jungle in Calais, my fellow researcher Léopold Lambert (2016) found that the camp is partially operated by Logistics Solutions a company that works for the Egyptian Army, which reminded me about companies like Serco that have become massive "detention corporations" in Australia. It is as though the state can practically create an extra-territory for itself, where the law doesn't apply, and outsource its humanitarian responsibilities.

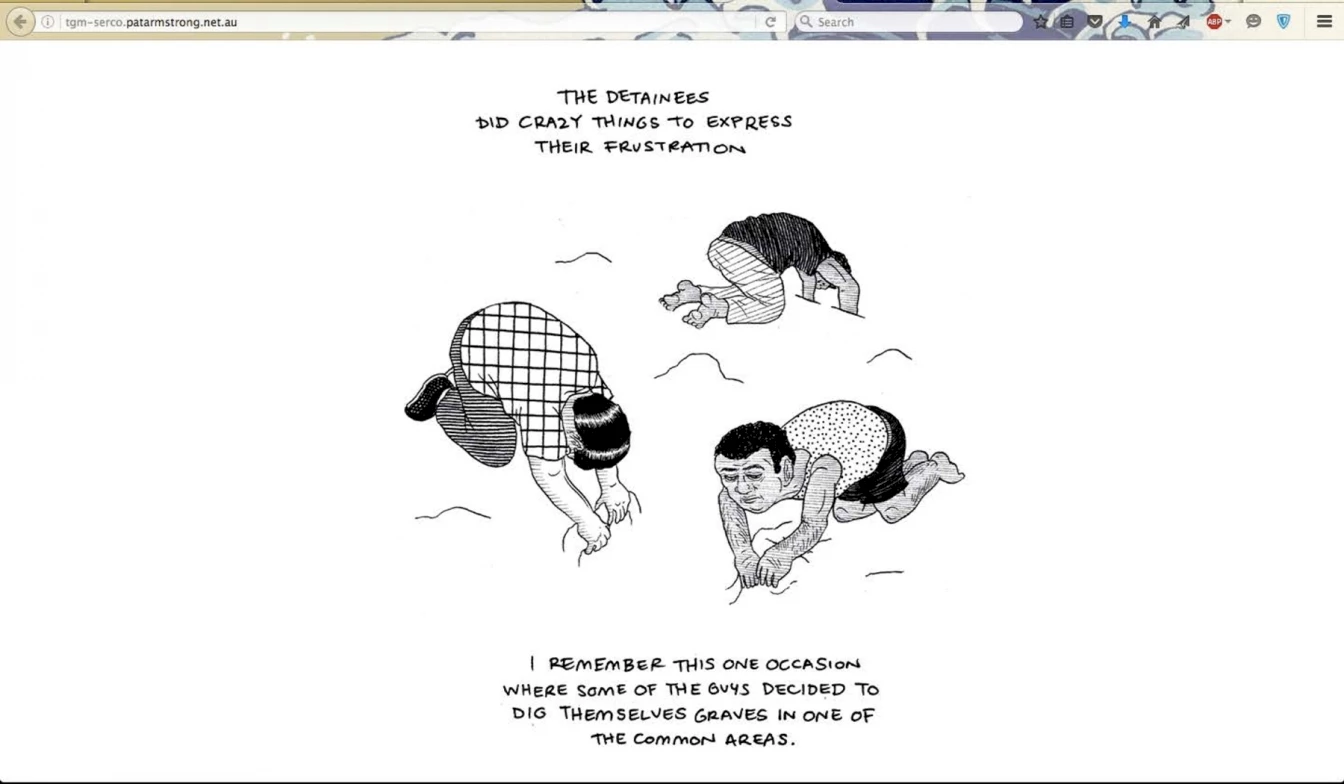

Drawings of the memories of a security officer in a detention centre in Australia. Photo: Sam Wallman. http://tgm-serco.patarmstrong.net.au

The Forensic Oceanography report on the Left-to-Die boat incident (2012) reached a similar conclusion; due to the creation of too many borders in the sea, to the states and other actors producing extra-territories where the definitions of responsibilities are blurred, a refugee boat sank as many vessels witnessed (Heller & Pezzani 2012). Another report by The Migrant Files collective listed all the deaths with the dates of the "accidents" in the Mediterranean.2 This list used to be prepared by UNITED for Intercultural Action, who could not keep up with such numbers for lack of people and funding after 2015.3

Michel Feher (2013–2015) points out the transformation of the modern state and the instrumentalisation of national borders, through which some wanted people and goods are encouraged to travel, while others become disposable. Walid Kowatlı adds to this argument, wishing that those modern notions of human rights or democracy were not branded so easily, as they seem "suspended" by implementation by now. Indeed, he adds that we should look for the difference between people or artefacts smuggled from Egypt to Italy, some end up in Lampedusa, others in Sotheby's.

Many of us 'in peace' have displayed our empathy for many of those 'in war' through charity. It is as if they are better away from our sight but still at our mercy – certainly most of us simply don't want them 'at home'. Most of us don't actually feel responsible for what has been happening, at most we feel guilty. In our conversation, remembering his university times in Sofia, Walid Kowatlı referred to the Bulgarians' Slavic Orthodox feeling of collective guilt, which is, for him, maybe the closest to responsibility. This was also an explanation as to why the Bulgarians didn't betray the Jewish people who were hiding from the Nazis in Bulgaria during the Second World War... Indeed, guilt seems to be another element in the infrastructure of our pain, but what is the difference between guilt and responsibility? Kowatlı considers that responsibility is about the future, and yet people don't want to think about the future in times of uncertainty.

James Baldwin once said most people don't feel responsible for what their governments have done in the past, and are still doing. He emphasised "the long view", as something we deeply need in the atmosphere of short-termism today, and considered the relationship between the past and the present in "making sense of responsibility". He added: "What I am demanding of and for other people is what I am demanding of and for myself" (Mead & Baldwin 1971).

As my mind seesaws between the refugee camps and the "dead rooms" people create for themselves so as not to see or hear or smelI, I want to conclude my notes with another statement by James Baldwin asking for a patient impatience: "We've got to be as clear-headed about human beings as possible, because we are still each other's only hope... Democracy does not have to mean the leveling of everyone to the lowest common denominator".

References:

Bauman, Z. 2006, Liquid Fear, Polity, Cambridge.

Borradori, G. 2003, Philosophy in A Time of Terror: Dialogues with Jurgen Habermas and Jacques Derrida, University of Chicago Press.

Feher, M. 2013–2015, "The Journey to Self-Esteem: How Human Capital Blossoms", Online Lecture Series, viewed 13 October 2016.

Heller C. and Pezzani, L. 2012, "The Case of Left to Die Boat", Report prepared for Amnesty International, Goldsmiths University, London, 11 April, viewed 13 October 2016.

Lambert, L. 2016, "Report from Calais and Grande Synthe (Part 1): Two Political Architectures of (in)Hospitality", The Funambulist, 21 April, viewed 13 October 2016.

Mead M. and Baldwin J. 1971, A Rap on Race, J. B. Lippincott, Philadelphia/New York.