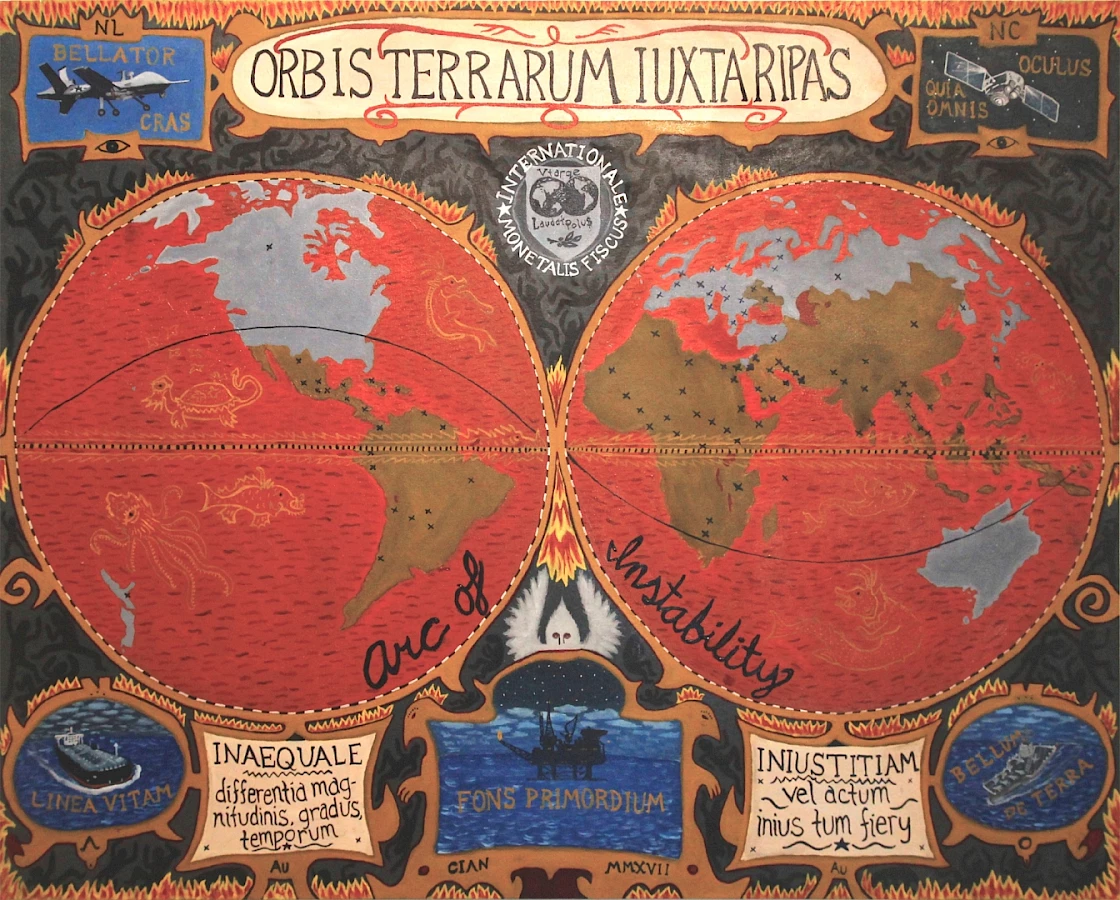

Cian Dayrit, Orbis Terrarum Iuxta Ripas, 2017. Oil on Canvas, 60 x 48 inches. Photo: At Maculangan.

This issue is the third in a series of e-publications edited by L'Internationale Online looking at concepts of political economy. Following the previous publications Austerity and Utopia and Degrowth and Progress, the present issue complicates two contested economic terms: class and redistribution. By inviting contributions from sociologists, political philosophers and artists, we seek to understand how these terms are utilised in institutional contexts and artistic practices.

Our approach challenges orthodox definitions of economic categories. Since the universal, ahistorical use of these categories is debatable, we accept, following historian Dipesh Chakrabarty, ‘the[ir] dual nature’, and interrogate their ‘intellectual and social histories.’1 It is urgent, for example, to question the Western cultural logic that governs financial practices and instruments such as insurance and property rights, and to expose the coloniality of an equation that synonymises productivity and profit, or custody and patrimony.

Class is a concept that engages many artistic practitioners. However, the meaning of class – as it was conceived and popularised in the early nineteenth century by Marx and Engels, as social relations contra their means of production – has changed radically as a result of social transformations. Feminist theory contests a narrow classification of labour based on commodified work and has instead made visible the spheres of non-commodified work, in order to theoretically dissolve the division between paid and unpaid labour. For this issue, leading Marxist-Feminist thinker Frigga Haug has delivered a transcript of an unpublished lecture from 2003, ‘Marxism within Feminism’, describing the associations between Marxist theory and the emancipation of women. Haug sheds light on a comprehensive set of subjects including work and labour between activity and practice, domestic labour, and socialist feminisms’ futures.

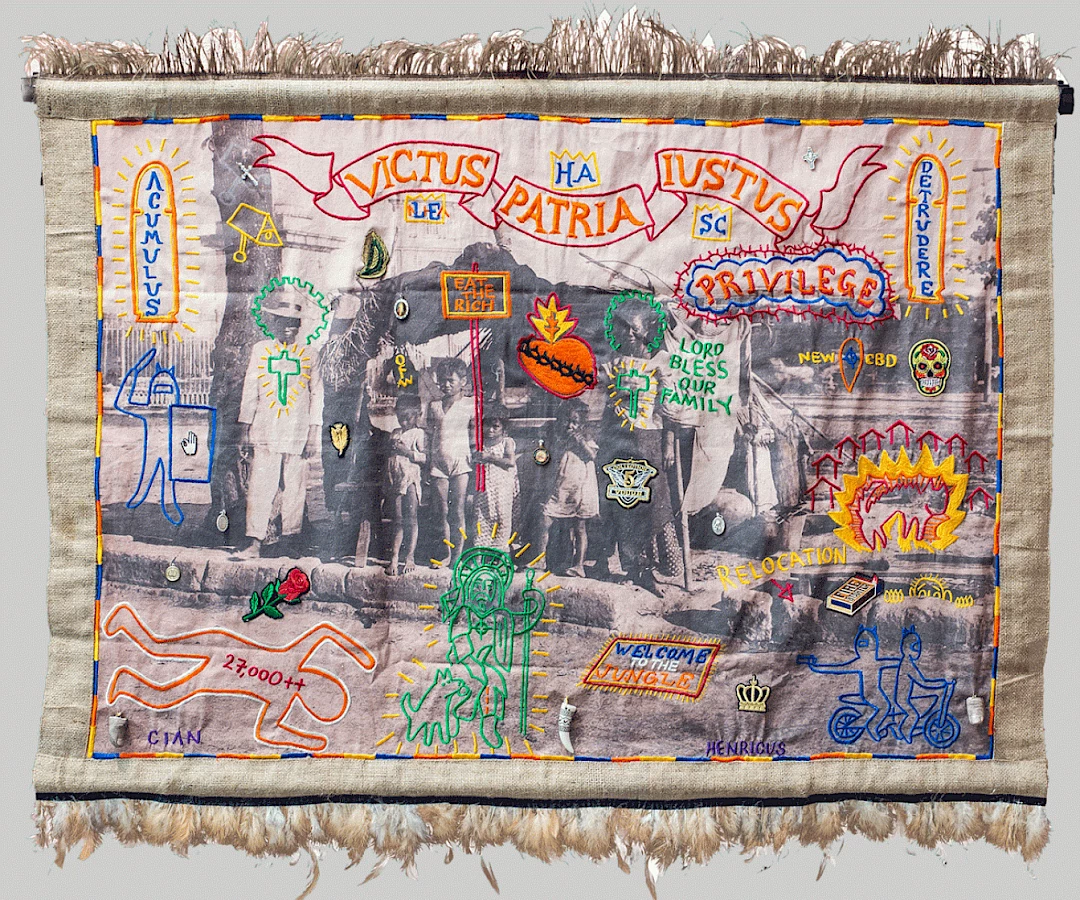

Cian Dayrit, The Currency of Plunder, 2019. Embroidery on textile, 65 x 45 inches. Photo: Mabini.

Postcolonial and feminist perspectives call for plurality, since the white European male (waged) class subject that underwrites Marx’s thinking can no longer be understood as an exclusive agent of transformation. How can alternative ways of perceiving class be advanced? Who is this ‘revolutionary subject’? Any exercise in consciousness-raising requires critical engagement with Marxist ideas, norms and beliefs, as they are embedded in postcolonial imaginations. This approach acknowledges that systems of representation and patterns of legitimisation are deeply sedimented with relations of power.

The protagonist of Aykan Safoğlu’s essay Aunt Yellow (2021) is his Aunt Zerrin, who moved from Turkey to Germany as a Gastarbeiterin (‘guest worker’) in the 1960s. Reflecting on ways of remembering, he scrutinises the issue of migrant labour through the lens of race, class and gender. Referencing Audre Lorde’s 1978 essay ‘The Uses of Erotic: The Erotic as Power’, Safoğlu attributes Europe’s recovery from the Second World War to the working womxn, like his aunt, whose migratory labour healed wounds, whether by having to concede their place as subjugated, feminised immigrants, or by managing to be active participants in society.

‘Feminist Movements in a Pandemic World – Towards a New Class Politics’ by Cinzia Arruzza was written for this issue at a moment when the failures of the prevailing macro-economic system which devalues caregivers have become all the more visible due the Covid-19 pandemic. Strikes led by women and gender-nonconforming people – from Chile to Palestine – function, moreover, to voice societal restlessness in the face of rapacious capitalism. Supplementing Arruzza’s contribution, we include the manifesto ‘On Social Reproduction and the Covid-19 Pandemic: Seven Theses’ (2020) by The Marxist Feminist Collective consisting of Tithi Bhattacharya, Svenja Bromberg, Angela Dimitrakaki, Sara Farris and Susan Ferguson.

Cian Dayrit, Eat The Rich, 2019. Embroidery, objects, digital print on textile, 62 x 45 inches. Photo: Katarzyna Perlak.

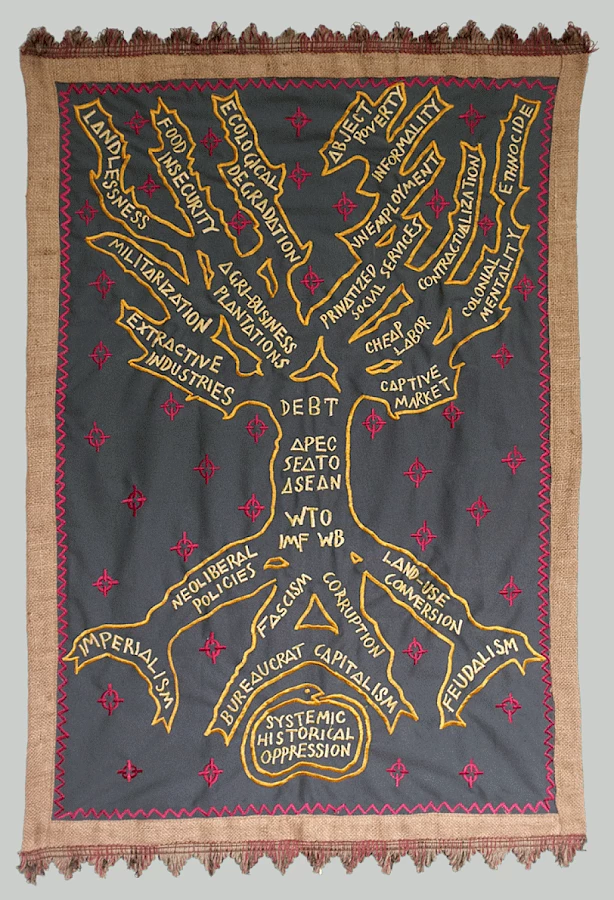

Cian Dayrit, Adversus Contradictores I, 2019. Embroidery on textile, 48 x 65 inches. Photo: Pinto.

Two works from Rafał Milach’s series The Archive of Public Protests (2018) document large-scale public demonstrations against the further restriction of reproductive rights in Poland; namely, access to abortion. The series shares its name with The Archive of Public Protests (APP), an autonomous group and platform of around eighteen photographers, co-initiated by Milach in 2015 with the purpose of recording and collecting the visual character of social and political antagonisms within their regional context. Resisting an indexical quality or singular aesthetic value, the archive functions to circulate and disseminate material when collective voices of dissent are stifled by the ruling doctrine.

Sharon Hayes’s In the Near Future, Warsaw (2008) was a performance in revisionism. Long interested in the intersection of public life and public art, Hayes reworked overheard or common slogans from historical demonstrations and resistance movements, and walked them around the streets of Warsaw, often as direct echoes to their original site of elocution. Text reading ‘Women Destroy Walls’ could be a sardonic reference to Jacek Kaczmarski’s 1978 protest song, ‘Walls’ – an anthem of the Polish trade union Solidarność (Solidarity) – as much as it could be a phrase from the contemporaneous iteration of the International Women’s Day Strike. Beneath the Palace of Culture and Science, banner in hand, Hayes reminds us that our stories often coincide, and that through disruption we may see their crossings.

The cultural production of ideas is not a self-determining process. How ideas interweave, overlap and counter fixed categories requires attention to the constructions of race, gender and sexuality against any notion of dominance. In this way, the economist Eiman O. Zein-Elabdin has developed the term ‘postcolonial economy’ and employed it in the contemporary African context. Zein-Elabdin conceives of an economic system embedded in cultures shaped by ambivalence and uncertainty that produce ‘unpredictable eco-cultural patterns.’2 Following this line of thought and positioning anti-colonialism and anti-racism within an intersectional Marxist-feminist framework, political theorist Françoise Vergès advances a decolonial analysis of accumulation in her text ‘On the Politics of Extraction, Exhaustion and Suffocation’ (2021).

Cian Dayrit, Adversus Contradictores II, 2019. Embroidery on textile, 48 x 65 inches. Photo: Pinto.

The spectre of global climate catastrophe is ever present, an important point in Vergès’s text. As communities in close proximity to hazardous waste facilities, landfills and large air polluters attest, we must be attentive to environmental human rights and theories of distributive justice to try to counteract a politics of destruction. Cian Dayrit’s counter-mapping practices and textile works examine ideas of cultural supremacy and identity as they are embodied and reproduced in the methodologies of maps, monuments and institutionalised forms of archiving. Dayrit’s works, informed by the experience of colonialism from the perspective of the Philippines, critique how imperialism and its ongoing aftermath destroy and diminish certain regions, while they also offer an imagination of alternative territories. Institutional and artistic practices guide us through an exploration of cultural belonging, reimagination and knowledge production. In the series of five drawings Marx Pather Bhumika 1 (2021), Naeem Mohaiemen reinterprets Bengali-language book covers from the radical tradition – on leftist concepts, Marxists theories and feminist emancipatory practices. With a nod to the circuits of reproduction, he questions the poetics of the revolutionary subject. Noah Fischer, an initiator of Occupy Museums and member of Gulf Labor Artist Coalition and G.U.L.F., targets the global systems and local conditions that exploit migrant workers and art workers with his dystopian cartoon series, The Giant Pit (2021). Taking the example of Guggenheim Abu Dhabi to fictionalise an unbuilt museum as one of its sites, the drawings make visible the crossings between economic and social inequity within art institutions.

The pandemic has firmly reminded us of the essential inconsistency within dominant systems that rank profits over the necessities of life-making or social reproduction. Social reproduction includes all relationships essential to the sustenance of life now and in the future. Care and domestic labour – cooking meals, caring for the elderly, or assisting in education – is an essential component of social reproduction, but not its only aspect. The cultivation of practices of community work or self-care produces social bonds and a healthy ecosystem. Opposing decline means caring for people, for the land, for local collectives, and for the direct reproduction of life.

Solidarity is assumed as the pursuit of equality-based relationships of interdependency. Ingela Ihrman’s video work Oilbird with Nestling (2021) reinforces awareness of a more-than-human nature with a potency to be valued, retelling the disengagement of humans from the convolution of environmental developments with the female artist body at its centre.

Cian Dayrit, Psidium Esse Perniciosius, 2020. Embroidery on textile, 30 x 42 inches. Photo: Cian Dayrit.