Eating clay is not an eating disorder

Zayaan Khan explores the qualities of clay - as food, as body, as memory, as witness, as story teller, as time machine. Khan’s encounters with clay, specifically that found at Devil's Peak in her home town of Cape Town, emerge from different forms of situated knowledge - scientific, sensorial, material and emotional. Closing with a recipe for Talbinah, a milky barley porridge, Khan pointedly asks: ‘What can I eat to fortify a broken heart?’

The act of eating things outside of what we consider food has the generalized label of pica, often seen in young children who explore the world through their mouths, but also in many older people who have the compulsion to eat non-food items that may be damaging to their health: spoons or other metal objects, soap, concrete, paint peeling off plaster (which may contain lead), even soil (which may be contaminated) – all of which may lead people to need urgent care or even surgery. Pica’s cravings have a sensory element. It is considered an eating disorder, listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) and subdivided into an array of Latin-worded disorders such as hyalophagia (the eating of glass, which brings up vivid memories of watching the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party and the wonderful crunches when they eat the teacups) or lithophagia (the eating of stones). There is a distinct dissonance around eating these non-food items, which gets everything grouped together under the banner of ‘disorder’, immediately creating a sense of othering. Imagine the stresses new parents go through when their mouth-sensory-seeking child is labelled as having an eating disorder when they explore the world and cannot differentiate between what to swallow and what not to swallow. Easy to simplify in black and white, but I would like to make some room here to think beyond the usual categories around or assumptions about what it is to eat that which is not considered food.

Pica is taken from the Latin name for magpie, Pica pica, birds known around the world for their intelligence, for their cultural practices, particularly around grieving, and for gleaning the shiny and the curious. Within a myriad of beliefs with folkloric and mythological associations, the magpie represents both good and evil in equal amounts: immense luck but also bad luck, depending on who you speak to. Kind of makes sense, then, the sweeping grouping of the eating of non-food items under this one banner. Still, I am motivated to make some space in this definition to claim that eating clay is not an eating disorder – that, in fact, we should nominate clay as a valid ingredient.

At the same time, I would like to create space for a new kind of eating: the deep satisfaction and craving for, the love and appreciation of foods with minimal flavour, especially delectable if they’re soft like air or paper. Like puff chips, but the lite version, minimally flavoured air chips – just a dusting of punch. There’s a sweetness of nothing there, or perhaps a sweetness in the nothing. My mother loves food like this, my mother who is also well-known for her most delicious traditional cooking skills, with spice and mountains of ingredients – but give her, let’s say, Japanese fluffy sponge cake (known around here as bread, even with its sweetness) and she will melt, not so much for the flavour but for the way the food seems to disappear as you bite into it, a solid food you can breathe in.

I nominate the love of these foods as insipiphilia – yes, insipi- as in ‘insipid’ but not in a negative way. Definitely not ‘lacking interest’, as dictionaries tell us, but inspi- as in, along the spectrum of ‘tasteless’. Have you ever craved rice paper? Or clay?

At the shop across the road from our house we used to buy rice paper for half a cent a sheet, an amount accessible to very young children. The way it would be ripped off its cardboard backing as it hung on the shelf in that dark and dirty old shop, then the softness it melted with as you manipulated it past your teeth – it satisfied the textural and sensorial cravings, but ultimately tasted like nothing.

Paper UFOs, the rice- or wafer-paper outer with delicious sour-sweet sherbet inner, the paper, offering a beautiful textural weight of nothingness, balancing out the sweetness and short shock of sour. White Rabbit Creamy Candy and other milk sweets of our childhood, toffee goodness wrapped in dry and also creamy rice paper. You meet a moment of nothing, of minimal flavour, in this salivation that mixes with the sweet milkiness.

This desire is so specific – for a texture more than a flavour perhaps? Or for the group of foods that lie along the nexus of soft–light–delicate in flavour and in taste (these being two different things).

Then there are the cravings that have mostly to do with texture, those where flavour or taste don’t really feature, those dubbed pica and considered an eating disorder. Twenty years ago I worked in retail and one of my coworkers on the cosmetics floor was pregnant and in her third trimester. She fondly told the story of how her husband drove her up to Devil’s Peak alongside Table Mountain, Cape Town, to where the old road led past an area of red slate. Here, after a short walk with incredible views of the city and harbour, she would harvest some of the clay, which was slaking off in pieces as the watery wall kept the slate soft. She recounted how she’d pick off pieces with glee to eat them right there with her front teeth (here she was specific: this was not a chewing affair, but a continual nibble), and packed some in a tissue for later. All along this walkway on the mountain are tributaries and waterfalls where clean icy cold sweet mountain water is ready to quench your thirst and help you wash down your serving of clay. Her craving was textural: the way the moisture had seeped in, the transition of moist to sodden, hardness into softness through eager teeth. She salivated, recalling her story, smacking her lips; you could still see the desire for that iron-slatey clay.

This craving exists around the world but is mostly known as an African custom. In South Africa, pieces of clay are sold at medicine stalls, at taxi ranks, by fresh produce hawkers, and so on, eaten sweet with a sprinkle of sugar or sprayed with some salt water (even sea water). Word on the street is, it is not considered an eating disorder but a common enough foodstuff. This land is so rich in all kinds of clay that the recognition goes beyond cultural and human–animal separations. What is this desire we have, all of us creatures who eat – dogs consuming concrete, people’s stories of craving old plaster – a kind of cool damp mineral need?

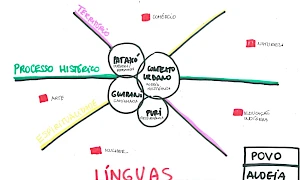

Mineral cravings take us to literal heights, from Alpine ibexes, climbing cliffs to lick salt deposits, to my coworker driving up the mountain. We crave that mineral clay, so much so that we should recognize it as an edible thing, as a food, if you will.

‘Crave that mineral’ meme, found on Tumblr, October 2014

The medicinal regard for clay is perhaps better known than clay as a foodstuff or cooking ingredient. Clay is recommended in cases of light poisoning where it is said to bind to the consumed contents, or as a detox, particularly for heavy metals, and in general for stomach or gut ailments, as it can stick to toxins and regulate the digestive tract. It is also used to dry out mouth ulcers or wounds. What a magic thing this clay is, to adhere to your loose stool while also being the main material of your toilet bowl and the tiles that surround it. Clay is the finest of geological components and can take some million years to form. It flows the furthest with water and will settle at the ultimate destination; to find clay, it is often just about following the flow. Clay stays suspended for a very long time, needing hours or days to settle after the water stills; it will stay in suspension as long as the water is in suspension too. It’s like a down feather dancing on a never-ending warm summer breeze. There’s a soft delight in this, in the plumage of clay in water.

From video footage of Devil’s Peak clay by Heather Thompson

The past few years I’ve been focusing on working with the terracotta-red clays that come out of Devil’s Peak, the mountain I grew up on and that my and my husband’s family grew up on. We have many stories of forced removal in our family, in our communities, and working with the land directly has helped to unlock some of the silent sounds I’d been picking up, distant calls through the veils, calling me. There’s a soft and deep listening, so clear but silent, so audible but only inside my mind. Hearing silence through inside ears, I try to find what I’m looking for as I walk this field I’ve walked so many times before. I imagine I can trace the lines of where the bulldozers moved, I see them in their chaos and through the crying and screaming of the forcibly removed. I see this all in the calm of day, walking to where my grandparents’ house was, where they refused to leave and were among the last to do so.

My grandfather always had this steely resolve, and I imagine how much this period influenced the rest of his years, till when I eventually met him two generations later. Something in him broke that day, as it must have in everyone when they were told to move from this neighbourhood to make space for white people who never moved in. The Group Areas Act of 1950 was a way the Apartheid government of South Africa could actualize their Apartheid Spatial Planning, architecturally designating the entire City of Cape Town (and the rest of the country) according to racial segregation, forcing entire communities out in order to create spaces for ‘Whites Only’. District Six is one such area, well known as it sits under the spectacular vista of Table Mountain, our Wonder of the World. Speaking with anyone who was from District Six, the value of this neighbourhood was the community’s wellness, the archetype of what Apartheid was trying to destroy: multicultural, multi-racial, a mix of religions and designations; people got along famously, neighbours cared for one another, children did not go hungry, even at strangers’ homes. There was always a place to rest your head, as my uncle would tell us. That all changed as people were moved. Less doors opened for weary travellers, pots stopped being placed on the stove in the early hours to ensure food for those who may need it. Apartheid, as part of the colonial project, aimed to destroy Indigenous ways of knowing and decimate the sense of community that was part of the natural solidarity of people who lived under severe oppression.

Section of fallow District Six at the foot of Devil’s Peak, with Table Mountain, flat as a table, behind. Foundations of homes and other buildings can be seen in the forefront. Photo: Zayaan Khan

Much has changed since then, but scratching beneath the surface, not much has changed, too. This land still lays fallow, never being forged into a suburb for ‘Whites Only’; I’ve walked here over and over, wondering about the dirt my mother kicked up with her friends, and, perhaps a couple hundred years before, what hyenas or lions or baboons had kicked up in their scuffle. Some millions of years before all of them, prehistoric animals stepped exactly where my mother later stood, regardless of what the land was doing at that time. We know that this land has been roughly the same for at least 1.5 million years, when the mountains were still an island and as the oceans receded.

There is a lot to witness in this place of nothing, with its makeshift housing and overgrown grass, boulders sticking out, the undulation of land as it cascades down the foot of the mountain. There are big witnessings and tiny ones too. I trace the new arrangements of sandstone rocks as people remove them or rearrange them over a beloved pet’s grave. I come to harvest fennel pollen in the warm times and clay in the seasons when the rain is just beginning. I come to listen to new stories: maybe the wind has remembered something for me, or the antlions have caught a new anecdote in their sandy trap. I trace the lines – this clay is leading me, from a Deep Time-line to all the forms this clay wishes to be – and I follow these lines and check for knots, check for breakages, let it all land inside me and manifest in the practice of making (whatever that making may be). Oftentimes, it feels as if my making is not up to me, so I sculpt and I make chalk and record sound and plan terracotta make-up palettes – what is all this, if not methods of storytelling?

Antlion nests where larvae wait in the central den of the dug-out pit and sense passing prey through the falling sand and clay particles. Photo: Zayaan Khan

This clay alludes to satisfaction, a textural perfection not found in many other edible things. It settles in the space of insipiphilia, a nothing taste that is full of texture – so astringent, it claims all your water for itself. Kind of slimy but smooth, a smodginess, if you will. Not as plastic in texture as you’d prefer for sculpting, but not impossible. This clay is so alive and raw, some excavated from deep underground and some superficially harvested. The invisible microbial worlds are fermenting it in wild ways. I have stored these bags of processed clay with just a bit too much water content so that fermentation kicks in and bubbles its way through the heart of the wedged clay loaves. They are growing, truly, more than any processed clay I’ve lived with; algal blooms, fungi, even a happy little slug are making their home there. The bubbling fermentation I cut through when I open a new bag makes me think of how the invisible ancient microbes who must still live in this clay, or at least in the now-aerobic environment they find themselves in, are being consumed by aerobic bacteria. We crave that mineral, after all.

Working with this clay is an immediate time machine. Forming over millions of years, not able to be synthesized, this clay must know things beyond our humble evolutionary assumptions. I wonder what the soil remembers and what stories these clay bodies would tell, and I’ve been focusing on letting the land know that we remember too. We live in a time of polycrisis – a time when crises upon crises are part of our lived experience – and, as is argued within epigenetics (the study of heritable traits), these crises and traumas are being passed on to generations who have not lived them. I see the trauma lingering in our communities, overlain by further traumas of modern-day extractivism and labour enforced simply to survive in this world. I see how lost I feel and how walking these lands offers me some sense of belonging, offers some answers to questions I don’t yet know how to ask. Our colonial heritage brought with it rounds of genocide, both through European illnesses and also mercenaries who, in the late 1700s and early 1800s, were sent to hunt and kill large animals by decree, including our people. They discovered there were cheaper ways to kill our people besides ammunition; they used parts of the land, like the rocks that had been here for millennia.

I learn these moments of history and I need to mourn. I need to return to the sea or to parts of the land and ask forgiveness on behalf of my humanity, to stress that we have not forgotten these stories and we will not rest until we right these transgressions, no matter how many generations it will take. We are hundreds of years away from that violence but we are still uncovering transgressions. We still feel it, we still discover it. We have had three rounds of colonial rule in our part of the world, ending with an unspeakably cruel Apartheid. This violence even seems tame in comparison with the apartheid and genocide we witness in Palestine today, enacted by Israel and largely funded by America, which keeps Palestinian lands, people, plants and animals in a constant state of separateness. With the transition to democracy, South Africa quickly accepted a free-market economy as a global trade value system, despite its severing of many people’s livelihoods as foreign investment with foreign gains entered South Africa, only benefiting those who had the money or the means to make this work. So still, we find ourselves ruled by extractive external powers, holding on to the threads of our own survival as the weight of the world’s crises keep the struggles alive.

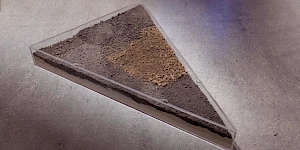

Close-up of dug-out clay, with iron-rich ochres in its colour-scape. Photo: Zayaan Khan

Somehow, my heart beats strong through all of this. My father’s family has cardiac weakness; they have died from heart attacks or broken hearts. I have learnt that our hearts inherit our spiritual stories, that they hear ancient tales and hold space for the emotional wealth that has been built up over generations. To grieve with this land is also a type of familial healing, an acknowledgement and processing of pain. Working with this clay, I have learnt a lot about my heart. It’s become a muscular metaphor for the processing of trauma, of becoming, of transitions, of relationships finding their ways in the world.

This clay goes through processes where it is wild and alive, full of stone and egg, insect carcasses and bacterial microworlds. It sits in my garden where so many different animals come to visit, poop in the clay, eat the clay, take clay away to build their own homes. Then I process the clay, refine it, separating the sand or stone detritus of forced removal from the microparticles of pure clay and metal minerals. Then, it sits for months as I carry on with the daily grind of family care. The processed clay gets wedged to remove any air pockets, which weaken the structural integrity once formed into sculpture, and sits for more time, amalgamating. Ideally I’d let it sit for years, but months will have to do. Sometimes it reaches a year or two and the clay is remarkably smoother and more pliable.

This clay is so precious to me: in my practice, I learn how it leans into some forms better than others, recycling it over and over again. Hardly anything of what I make goes through the intense heat of the kiln’s furnaces, where it turns to ceramic once all traces of water are removed – I would say only about 30 percent. I prefer to make new forms, and when they dry, I break these clay bodies into a bucket of water, and they soak it up into every crack and pore, meeting every molecule to stay bonded. Clay, as opposed to ceramic, is raw and wild, soft and powdery when dry, and stone-hard when appropriately baked. In clay, there’s something about the relationship between water and land, where all the sounds of both the invisibles and the visibles enter the material; there are clues and hints from a time long before harvesting it, which settle in my ears as I work. In the digging and excavation that exposes this clay through the sandstone sediments, am I hearing some Deep Time memories?

I am convinced by clay, convinced by its satisfaction. I trace new recipes with it, why not, tempted to involve the clay in recipes for the heart. What can I eat to fortify a broken heart? When faced with questions beyond our immediate knowledge, I turn to our heritage to see where answers may rise up. Growing up in Islam has taught me immensely about the scope of acceptance grief will give you; how much it stretches your capacity to love, how much it is necessary to heal. There is also a particular calm to the fact that there is a sunnah recipe for grief1, for deep sadness, based on barley flour, milk, a touch of dates or honey, and the simple act of making porridge2 – recipes dating back at least 1,400 years, which stay humble in their simplicity. This Prophetic Medicine helps to form a road map for adopting recipes as ways to navigate worldly problems, as digestible methods of processing grief.

In the time I have been learning from this clay, I have been learning about love as an ancient force, about romantic love and familial love and the way souls meet each other in a sacred place before landing in our fallible earthly bodies. I have also been pregnant in this clay time, and can’t help but acknowledge metaphors of our bodies being made of clay, now that I understand what clay truly is: just the mineral detritus of all life in a particular place and time, contained in and passed through geological Deep Time, the slowest, most reliable time. Much like souls and much like love, there is something about the way my heart became clay in this time, too, especially when I recycle the sculptural work I’ve made, placing it into water to rehydrate, and I put my ear to the water and hear the gradual slaking of the clay as the water enters its body. It’s like the process of a gentle heartbreak, where you are still held in the support of all this perfect water, but you, or the clay, gently fall, falls, apart, fizzing and whizzing, bubbling and collapsing into a fine powder, becoming one with the water, eventually settling at the bottom of the bucket, ready to be dried and wedged and sculpted into new, more powerful forms. This process is much like the aches we inherit and the breaks we go through in our fallible bodies in our fallible lives, where, when the heart breaks but is not broken completely, when it is made anew, there is more potential for fortitude.

From footage of Devil’s Peak clay by Heather Thompson

In this process of renewal I find myself needing to go back to knowing nothing, to be led instead of leading, to lean on other recipes and not create my own. But still, this clay is asking to be yielded, asking to be met with satisfaction, which relays a kind of reciprocity in the relationship. I wonder about a full circle in the metaphoric of being clay-made and of eating clay, as opposed to eating out of clay. Clay is no longer only the food vessel (or wall or floor or roof dressing, among other home necessities), it is remembered as the vessel of our bodies, while we are also eating clay. A strange cannibalism, perhaps, but really a longing for connection, for reclaiming our place in a world run according to necropolitics in the guise of sustainability goals or economic empowerment.

A sliced date collapses into the merciful warmth and comfort of talbinah, a recipe for sunken hearts. Photo: Zayaan Khan

In this moment, I offer a recipe as an attempt at reconnection, as an offering for some ease: Our recipe for Talbinah, the gentle milky barley porridge, with a generous dusting of the clay from this land.

Ingredients:

One cup of milk

Two to three tablespoons of barley flour. We prefer to toast it a little bit before, freshly ground is best.

An offering of prehistoric clay, a spicing of memories, stories and secrets. Just enough to draw in astringency but not enough to detract from the creaminess.

One teaspoon of ghee

One teaspoon of honey

One deseeded date

Method:

Heat up the milk gently and as it climbs, dust in the barley flour, sieving the hard bits out. Stir after each tablespoon, this ensures even texture.

Serve with a teaspoon of ghee and a teaspoon of honey. Garnish with a date when the porridge is still piping hot, let the date collapse and soften.

May this warm your heart and enrich your future memories.

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–VCRC

Kyiv Biennial 2023

L’Internationale Confederation is a proud partner of this year’s edition of Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Where are the Oases?

PEI OBERT seminar

with Kader Attia, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Emily Jacir, Achille Mbembe, Sarah Nuttall and Françoise VergèsAn oasis is the potential for life in an adverse environment.

-

MACBA

Anti-imperialism in the 20th century and anti-imperialism today: similarities and differences

PEI OBERT seminar

Lecture by Ramón GrosfoguelIn 1956, countries that were fighting colonialism by freeing themselves from both capitalism and communism dreamed of a third path, one that did not align with or bend to the politics dictated by Washington or Moscow. They held their first conference in Bandung, Indonesia.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production

The Studies Center of Museo Reina Sofía will publish an open call for four residencies of artistic practice for projects that address the emergencies and challenges derived from the climate crisis such as food sovereignty, architecture and sustainability, communal practices, diasporas and exiles or ecological and political sustainability, among others.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

Maria Lugones Decolonial Summer School

Recalling Earth: Decoloniality and Demodernity

Course Directors: Prof. Walter Mignolo & Dr. Rolando VázquezRecalling Earth and learning worlds and worlds-making will be the topic of chapter 14th of the María Lugones Summer School that will take place at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven.

-

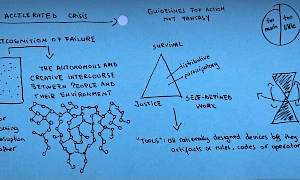

–tranzit.ro

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Archive of the Conceptual Art of Odesa in the 1980s

The research project turns to the beginning of 1980s, when conceptual art circle emerged in Odesa, Ukraine. Artists worked independently and in collaborations creating the first examples of performances, paradoxical objects and drawings.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school is organised by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in partnership with ZRC SAZU (the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts) as part of the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–MACBA

Song for Many Movements: Scenes of Collective Creation

An ephemeral experiment in which the ground floor of MACBA becomes a stage for encounters, conversations and shared listening.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

–M HKA

The Lives of Animals

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at M HKA that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ is a series of sound installations by Özcan Ertek, Fulya Uçanok, Ömer Sarıgedik, Zeynep Ayşe Hatipoğlu, and Passepartout Duo, presented at Salt in Istanbul.

-

–SALT

Sound of Green

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ at Salt in Istanbul begins on 5 June, World Environment Day, with Özcan Ertek’s installation ‘Sound of Green’.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Open Call: Research Residencies

The Centro de Estudios of Museo Reina Sofía releases its open call for research residencies as part of the climate thread within the Museum of the Commons programme.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–

Kyiv Biennial 2025

L’Internationale Confederation is proud to co-organise this years’ edition of the Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica

Curated by MACBA director Elvira Dyangani Ose, along with Antawan Byrd, Adom Getachew and Matthew S. Witkovsky, Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica is the first major international exhibition to examine the cultural manifestations of Pan-Africanism from the 1920s to the present.

-

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

–SALT

The Lives of Animals, Salt Beyoğlu

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at Salt that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Plant(ing) Entanglements

The series of sound installations Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them ends with Fulya Uçanok’s sound installation Plant(ing) Entanglements.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production. Research Residencies

The projects selected in the first call of the Sustainable Art Practice research residencies are A hores d'ara. Experiences and memory of the defense of the Huerta valenciana through its archive by the group of researchers Anaïs Florin, Natalia Castellano and Alba Herrero; and Fundamental Errors by the filmmaker and architect Mauricio Freyre.

-

–

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Study Group: Aesthetics of Peace and Desertion Tactics

In a present marked by rearmament, war, genocide, and the collapse of the social contract, this study group aims to equip itself with tools to, on one hand, map genealogies and aesthetics of peace – within and beyond the Spanish context – and, on the other, analyze strategies of pacification that have served to neutralize the critical power of peace struggles.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Near East, Far West. Kyiv Biennial 2025

The main exhibition of the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, titled Near East, Far West, is organized by a consortium of curators from L’Internationale. It features seven new artists’ commissions, alongside works from the collections of member institutions of L’Internationale and a number of other loans.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: The Brighter Nations in Solidarity: Even in the Midst of a Genocide, a New World Is Being Born

PEI Obert presents a lecture by Vijay Prashad. The Colonial West is in decay, losing its economic grip on the world and its control over our minds. The birth of a new world is neither clear nor easy. This talk envisions that horizon, forged through the solidarity of past and present anticolonial struggles, and heralds its inevitable arrival.

-

–M HKA

Homelands and Hinterlands. Kyiv Biennial 2025

Following the trans-national format of the 2023 edition, the Kyiv Biennial 2025 will again take place in multiple locations across Europe. Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA) presents a stand-alone exhibition that acts also as an extension of the main biennial exhibition held at the newly-opened Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN).

In reckoning with the injustices and atrocities committed by the imperialisms of today, Kyiv Biennial 2025 reflects with historical consciousness on failed solidarities and internationalisms. It does this across an axis that the curators describe as Middle-East-Europe, a term encompassing Central Eastern Europe, the former-Soviet East and the Middle East.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Bodies of Evidence. A lecture by Ido Nahari and Adam Broomberg

In the second day of Open PEI, writer and researcher Ido Nahari and artist, activist and educator Adam Broomberg bring us Bodies of Evidence, a lecture that analyses the circulation and functioning of violent images of past and present genocides. The debate revolves around the new fundamentalist grammar created for this documentation.

-

–

Everything for Everybody. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Everything for Everybody’ takes place in the Ukraine, at the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture.

-

–

In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture’ takes place at the Dovzhenko Centre in Kyiv.

-

MACBA

School of Common Knowledge: Fred Moten

Fred Moten gives the lecture Some Prœposicions (On, To, For, Against, Towards, Around, Above, Below, Before, Beyond): the Work of Art. As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA presents this lecture on artworks and art institutions in relation to the challenge of blackness in the present day.

-

–MACBA

Visions of Panafrica. Film programme

Visions of Panafrica is a film series that builds on the themes explored in the exhibition Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, bringing them to life through the medium of film. A cinema without a geographical centre that reaffirms the cultural and political relevance of Pan-Africanism.

-

MACBA

Farah Saleh. Balfour Reparations (2025–2045)

As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA is co-organising Balfour Reparations (2025–2045), a piece by Palestinian choreographer Farah Saleh included in Hacer Historia(s) VI (Making History(ies) VI), in collaboration with La Poderosa. This performance draws on archives, memories and future imaginaries in order to rethink the British colonial legacy in Palestine, raising questions about reparation, justice and historical responsibility.

-

MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica OPENING EVENT

A conversation between Antawan I. Byrd, Adom Getachew, Matthew S. Witkovsky and Elvira Dyangani Ose. To mark the opening of Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, the curatorial team will delve into the exhibition’s main themes with the aim of exploring some of its most relevant aspects and sharing their research processes with the public.

-

MACBA

Palestine Cinema Days 2025: Al-makhdu’un (1972)

Since 2023, MACBA has been part of an international initiative in solidarity with the Palestine Cinema Days film festival, which cannot be held in Ramallah due to the ongoing genocide in Palestinian territory. During the first days of November, organizations from around the world have agreed to coordinate free screenings of a selection of films from the festival. MACBA will be screening the film Al-makhdu’un (The Dupes) from 1972.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Cinema Commons #1: On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes

On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes is a Museo Reina Sofía film programme overseen by Miriam Martín and Ana Useros, and the first within the project The Cinema and Sound Commons. The activity includes a lecture and two films screened twice in two different sessions: John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948) and John Gianvito’s The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (2001).

-

–

Vertical Horizon. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Vertical Horizon’ takes place at the Lentos Kunstmuseum in Linz, at the initiative of tranzit.at.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Until Liberation: A Collective Reading and Listening Session by Learning Palestine

PEI Obert presents a collective session with Learning Palestine. At this historical juncture – amid the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the censorship and repression of all things Palestinian – Learning Palestine invites us to gather not only in refusal but also in affirmation.

Related contributions and publications

-

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Pollution as a Weapon of War

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimate -

The Kitchen, an Introduction to Subversive Film with Nick Aikens, Reem Shilleh and Mohanad Yaqubi

Nick Aikens, Subversive FilmSonic and Cinema CommonslumbungPast in the PresentVan Abbemuseum -

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Pollution as a Weapon of War – a conversation with Svitlana Matviyenko

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Françoise Vergès – Breathing: A Revolutionary Act

Françoise VergèsClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Ana Teixeira Pinto – Fire and Fuel: Energy and Chronopolitical Allegory

Ana Teixeira PintoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Watery Histories – a conversation between artists Katarina Pirak Sikku and Léuli Eshrāghi

Léuli Eshrāghi, Katarina Pirak SikkuClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

The Veil of Peace

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuPast in the Presenttranzit.ro -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: The Arrow of Time

Catherine MorlandClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Reading list - Summer School: Our Many Easts

Summer School - Our Many EastsSchoolsPast in the PresentModerna galerija -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Dispatch: ‘I don't believe in revolution, but sometimes I get in the spirit.’

Megan HoetgerSchoolsPast in the Present -

Dispatch: Notes on (de)growth from the fragments of Yugoslavia's former alliances

Ava ZevopSchoolsPast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

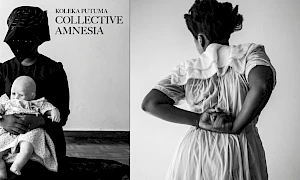

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Present Present Present. On grounding the Mediateca and Sonotera spaces in Malafo, Guinea-Bissau

Filipa CésarSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the Present -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Reading list: October School. Reimagining Institutions

October SchoolSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimateMSU Zagreb -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

Some Things We Learnt: Working with Indigenous culture from within non-Indigenous institutions

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteLand Relations -

How to Keep On Without Knowing What We Already Know, Or, What Comes After Magic Words and Politics of Salvation

Mônica HoffClimate -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations