Fail Better – Artistic Interventionism in Dakar in the 1990s and Today: Nick Aikens in conversation with Clémentine Deliss

El Hadji Sy in his studio at Tenq, 1994, St. Louis du Sénégal as part of 'africa95'. Photo: Djibril Sy.

Nick Aikens: Could you begin by talking about the context in which you became involved with Tenq artists’ workshops and the Laboratoire Agit'Art collective in the early 1990s?

Clémentine Deliss: Between 1992 and 1994 I was travelling around the African continent to meet artists. This was prompted by a seminar I set up at SOAS in London in 1991 on ‘African Art Criticism’, where I invited speakers like art critic Stuart Morgan, and Olu Oguibe, who had just finished his PhD on Nigerian artist Uzo Egonu, or British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare with art collector Robert Loder, to give parallel talks which would confront the assumption, published in art catalogues at the time, that there was no intellectual debate happening within and around the African continent. This led me to go and see Norman Rosenthal, then Exhibitions Secretary of the Royal Academy of Arts (RA). The RA was planning a comprehensive pan-continental exhibition called ‘Africa: The Art of a Continent’.1 But they were reluctant to include any practices from the twentieth century. A small committee was formed, which included – along with Rosenthal, Loder, and English artist Tom Phillips – the Nigerian novelist Simi Bedford; Ghanaian-born, London-based publisher and writer Margaret Busby; Guyanese-born, London-based film curator from the BFI June Givanni; Nigerian dancer and performer Peter Badejo; film-maker John Akomfrah; and curator Mark Sealy of Autograph (Association of Black Photographers). I was commissioned to travel to Africa in order to mediate between artists and curators there and potential venues in London and around the UK. The aim was to run a wider programme of events, ‘africa95’, at the same time as the RA exhibition. I visited twenty countries, mainly alone, going underground to find artists with whom I could exchange ideas. I was interested in particular in the urban situation. It was in this context that I first met Senegalese artist, activist and curator El Hadji Sy and became involved in Laboratoire Agit'Art.

NA: And could you describe the artistic milieu in Senegal at the time?

CD: There was a lot going on. There was Binette Cissé’s gallery in the 1960s building ‘Les Allumettes’ on Place de l’Indépendance, called simply 8F (eighth floor, door F). I met many artists, architects, critics, collectors, bankers, a lawyer working with Spike Lee, and you could sense a vibrant interconnected and intellectual art world. In the early nineties, development agencies were only just beginning to realise what they could achieve with the input of artists. Until then, the European Union and other foreign agencies and NGOs in West Africa focused on language-skills and infrastructural or technical needs, but they didn’t think the arts were particularly useful to them.

Then in 1992, the EU delegation in Dakar and the French government funded the first edition of Dak'Art (Biennale de l’Art Africain Contemporain). El Hadji Sy actually boycotted the biennale’s first edition, installing his large paintings on rice sacks in the streets of a working-class neighbourhood in response. Some artists were wary of the European officialdom surrounding the biennale and felt the need for greater autonomy, for an artistic interventionism that could speed up the process of change. If the Senegalese government wasn’t acting fast enough, and the foreign agencies were worried about long-term sustainability and handing out funds to artists, then it was left to these same artists to try – in a militant but social way – to set up new structures. By 1992, a number of exhibitions of contemporary art from Africa had taken place in Europe and the US that were being debated and criticised by intellectuals and artists in Dakar. Jean Pigozzi was collecting through curator André Magnin, and Susan Vogel’s ‘Africa Explores’ exhibition, across the Museum of African Art and the New Museum in New York (1991), with its categories of ‘extinct art’ and ‘traditional art’, had irked artists all over the African continent.

In 1977, El Hadji Sy, who had just completed his studies of fine art at the Institut des Arts du Sénégal, and his artist friends, dissatisfied by President Senghor’s failure to set up the Cité des Arts, intended to be a multidisciplinary art centre, squatted a former French military building on the Corniche in Dakar. It was here that Tenq first emerged in 1980 as a gallery space within the larger studio complex, which the artists ironically called the Village des Arts. The space was open for a few years until the military turned up at dawn in September 1983, throwing the artists and their works onto the street. El Hadji Sy turned this disastrous moment into an exhibition on the roadside, but never forgot the violence of the state. Taking over defunct colonial or socialist architecture is what artist Ibrahim Mahama also did thirty years later when he purchased a former Soviet grain silo and cemetery in Tamale, Ghana. The difference is that then, El Hadji and his peers were squatting – they were not selling enough artworks that they might purchase buildings. I’m not even sure that ownership was a prerogative for them. Alongside Tenq, there was the Laboratoire Agit'Art, a much more fluid and complex collective of artists.

Players and Groupings from 1992 onward. Collated by Clémentine Deliss.

NA: Is there documentation of this first moment of Tenq?

CD: Perhaps. But I’ve not seen much of it. The question of documentation was always suspended among the players of Tenq and Laboratoire Agit'Art. None of them seemed interested in the discussions around the archive and conservation that we are familiar with today. ‘Where is the archive of Laboratoire Agit'Art?’ is asked again and again. It still remains a mystery. The collective was non-bureaucratic and difficult to commodify. When Issa Samb aka Joe Ouakam died in 2017, someone removed the contents of his studio. So we shall have to wait and see when the materials emerge.

NA: How would you describe the Laboratoire Agit'Art?

CD: It was like a parapolitical aesthetic infrastructure, a micro-government. It was intriguing because you weren’t ever really able to know who was a member and who was not, or how extensive it was. I remember sitting and writing in the courtyard of Issa Samb’s studio space in the centre of Dakar, which acted as the crucible of the Laboratoire. Somebody would walk in who was an advisor to the president (at that time, Abdou Diouf), but this advisor also turned out to be a renowned poet, who ran a literary venue. A short while later, someone else would arrive – maybe the president’s physiotherapist, who was also an art collector. And then there were the central figures including film-maker Djibril Diop Mambéty; actor Pap Oumar Makéna Diop; his brother, dramaturge Abdoulaye Dani Diop; photographer Bouna Médoune Sèye; philosopher As M’bengue; Issa Samb and El Hadji Sy. It was an extraordinary constellation of people – mostly men, I should add.

Issa Samb and El Hadji Sy, Dakar, 1996. Photo: Clémentine Deliss.

When I was in Dakar in the nineties, the group was fractured by the death of a key member, playwright Yussufa John. Originally the Laboratoire Agit'Art was a sort of anti-theatre group that performed against the genre of national theatre promoted by poet-president Léopold Sédar Senghor. Yussufa John had emigrated from Senegal to Martinique, where he died quite suddenly in 1995. Between 1994 and 1998, the core activities of the Laboratoire were constituted by Issa Samb, El Hadji Sy and a tight group of interlocutors, including myself. I spent a lot of time in the capital and even had an apartment there. I would hang out with the group – we would go from one bar to the next, drinking and planning. A lot of the work we did was at night, and so was mostly invisible, which is counter to how you might think of interventionism.

At that moment in the mid-nineties, there was a sense of encroaching visibility in art and curatorial practice. Things had to be visible to the public and accessible to be legitimate. What I like with the Laboratoire Agit'Art is that we would work together on phenomena so fleeting they cannot be either captured in the moment or seen, such as the presence of the voice.2 We would have these intense conversations about methodology; at times it felt initiatory. It was in 1995 that I was invited to become a member, following our intervention at the conference ‘Mediums of Change’, chaired by Stuart Hall at SOAS as part of ‘africa95’. Later I tried to excommunicate myself from the Laboratoire, when I felt that Samb and Sy were giving away the keys to the house, so to speak, but I was told: Once a member, always a member!

NA: Clémentine, you tend to talk about a Tenq – as a thing rather than as a group of people or a process. Could you perhaps give readers a definition of a ‘Tenq’?

CD: ‘Tenq’ means articulation in Wolof. I would say it is desmological – a branch of anatomy, from desmos, which refers to ligaments, nodes, connections. A Tenq event or workshop would bring different parties and voices together to articulate something in a set space of time. The first iteration I experienced was connected to Triangle Artists’ Workshop. Robert Loder and English sculptor Anthony Caro had initiated the Triangle workshops in 1982, bringing artists from the UK to upstate New York. No critics were ever invited, no family members, academics or curators could be present – these workshops were always artist-led and artist-run. It was about getting artists together for two weeks to jam. So while Loder provided the germ of the idea for the collaboration, he stayed very much in the background. He was the ultimate éminence grise. When he met El Hadji Sy, who would become a co-curator of the Whitechapel exhibition ‘Seven Stories about Modern Art in Africa’,3 Loder realised that here was a guy who had done quite a bit of activism in Dakar, and so he suggested they might initiate a Triangle-style workshop in Senegal. There had been Triangle workshops in South Africa and Botswana – I think that was one of the first times Chris Ofili used elephant turds to prop up his paintings. I was slightly critical of Loder’s concept because it was so anti-intellectual.

Amédy Kré Mbaye, Tenq, 1994, St Louis du Sénégal as part of 'africa95'. Photo: Djibril Sy.

El Hadji Sy agreed to run a workshop, and his ‘Tenq 94’ was the first event of the ‘africa95’ season. To find a location, Sy and I travelled to the northern coastal town of Saint-Louis du Sénégal where we met a headteacher who said something along the lines of: ‘Look, the Lycée is shut for six weeks – take it over! The classrooms are empty.’ Tenq 94 took place at the Lycée Cheikh Omar Foutiyou Tall (formerly Faidherbe), and we invited as many artists as we could from outside of Senegal. That was the key concern at the time: to gather artists together and break the isolation they felt between African countries. Remember that there was not yet any internet, no one had a mobile phone. Fax machines were the only way you could communicate between places, or with express post and landlines. Yinka Shonibare and Anna Best joined from London, Flinto Chandia from Zambia, Atta Kwami from Ghana, David Koloane from South Africa, and many more. It really was a remarkable set of artists.

Sy, along with our small group of artist collaborators, raised all the money for it. Some funding came from a Senegalese bank, another part came from the British Council, who flew over the artists from the UK. At that time this kind of patchwork of finance mirrored the patchwork of participation, in a positive way. You didn’t have something funded by one corporation, one institution, or even one country.

NA: That’s also very different to the art-market-reliant infrastructure you see with Ibrahim Mahama or Theaster Gates, for example, which is wholly dependent on one person selling artworks in order to fund a collective project.

CD: Absolutely. Even though all works that came out of a Tenq workshop were understood as unfinished, it was also important that at the end of the fortnight, there was a kind of public exhibition.

The second major Tenq I was involved with took place in 1996 in Dakar. I was given a contract by the European Union to go to Dakar to support the third edition of the art biennale. The EU was aware that if I took part, I would bring another crowd with me. Until then Dak'Art had been monopolised by small French galleries selling ‘tribal art’ and who were miles away from the rest of the contemporary art world. There was also prominent input from Revue Noire edited by Simon Njami, Jean Loup Pivin and Pascal Martin Saint Léon,4 but they had their own publication, whereas I was an independent curator.

So it was that the then Minister of Culture of Senegal, philosopher and novelist Abdoulaye Élimane Kane, became involved in the realisation of this edition of Tenq. I shall never forget spending hours in his office in ‘Le Building’ (Dakar’s large 1960s governmental administrative building), talking openly about infrastructure, about artist-led initiatives, about what one could do. We were still desperately searching for a location to hold this Tenq in time for the opening of Dak'Art 1996. Kane offered: ‘There’s a Chinese village near the old airport with eleven empty barracks that no one has used for eight years, because after the Chinese migrant workers had finished building the city’s sports stadium in the 1980s, they left. If you want, you can have that.’ The Chinese had been commissioned to build stadiums by numerous West African states in that era in exchange for diplomatic support and to gain fishing rights.

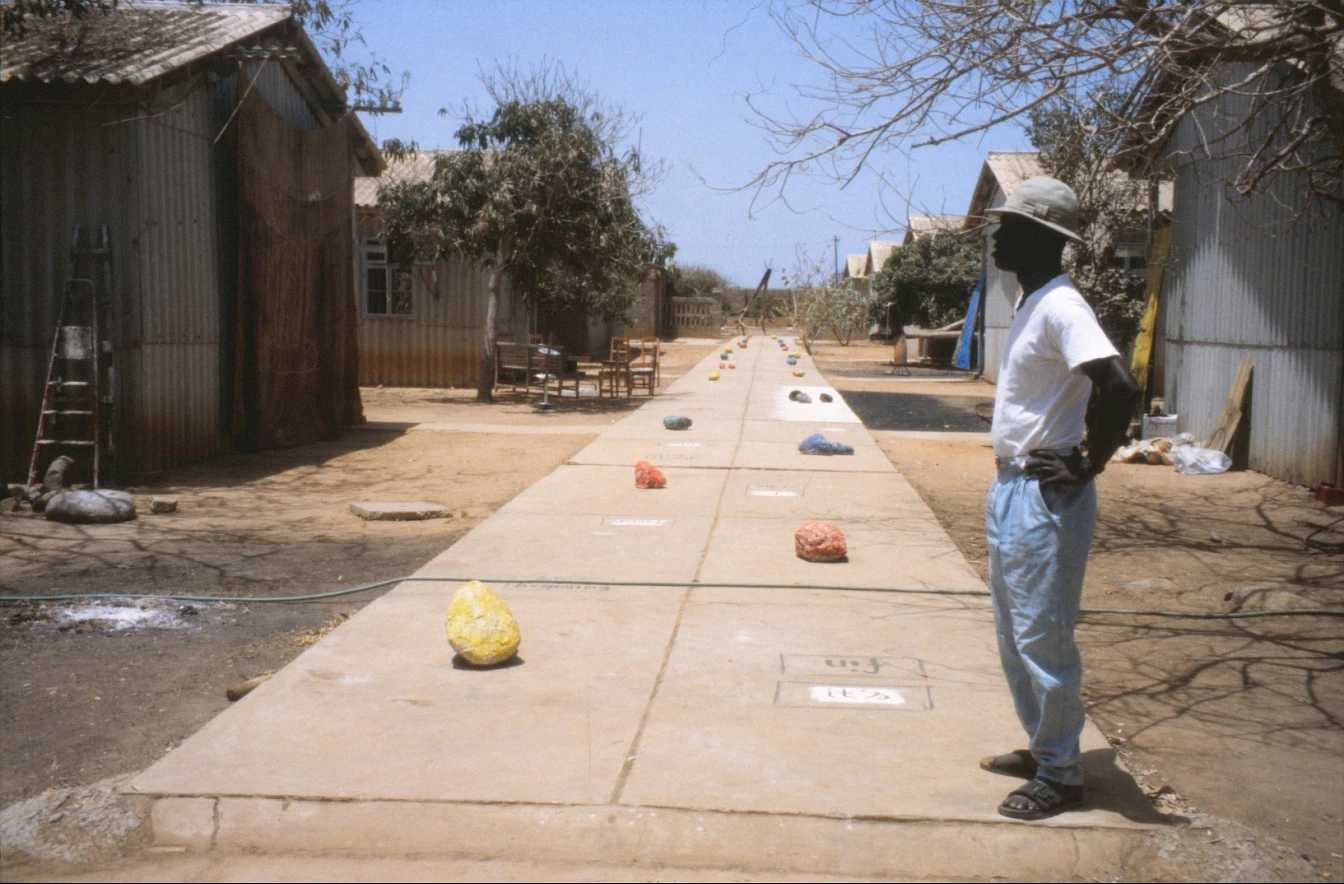

El Hadji Sy in the former Chinese camp renamed Village des Arts. Floor painting by Kan-Si. Photo: Clémentine Deliss, 1996.

El Hadji Sy, myself and the Tenq group agreed to have a look. We planned everything from my apartment, and then went back to see the minister. He literally gave us the key and we took cabs out to the Chinese village. All the signs were in Mandarin and the canteen had a banner saying ‘Happy Chinese New Year!’ There were storage rooms full of ginseng, a brick-making machine, and piles of maps and technical drawings by Chinese engineers, which stupidly we didn’t hold on to. We asked a youth club to clear out the bushes and snakes. There was no electricity but there was running water. The Chinese had lived here with complete self-sufficiency, excellent systems of irrigation, and orchards of mango trees, but by then it was very rundown. We knocked through some of the partition walls of the barracks to make larger studios. And there were three weeks to go.

A gallery space was set up in the former canteen and a manifesto announcing the opening was pasted onto the shed walls. All our guest artists came to spend two weeks living and working together on site: Johannes Phokela from South Africa, Chika Okeke-Agulu from Nigeria, Yacouba Touré from Burkina Faso, and many more. Knowing I was in Dakar, North American artist Christopher Williams and his assistant Miles Coolidge came over and shot the beautiful photographs of Heidelberg machines in the same printers where I produced the first issue of Metronome.5 Curators Catherine David and Peter Pakesch flew from Europe to Dakar, as did Swiss artist Renée Levi.

A year later, when I took part in David’s curation of documenta X, ‘100 Days’, El Hadji Sy came too. David was the one to coin the term ‘aesthetic practices’, which opened up the parameters of contemporary art. When Senegalese artist and collaborator Kan-Si said we had ‘stepped down from the pedestal’ and stopped being ‘cloistered’ to set foot in lived experience, this is exactly what was happening.6 ‘Tenq 96’ had an inflammable character – between local cycles of artists’ squats and government evictions, on the one hand, and the demands for accelerated production and visibility commanded by this new internationalism, on the other. And although the occupation of the site was not intended to last beyond the two-week session, El Sy and several of the core Tenq members have been based there ever since.

In the 1990s there was little space for communication between artists working with different interventionist strategies across the world. Danish artist group Superflex took their biogas project and placed it in a Tanzanian context, but their work was totally different to that of Senegalese collective Huit Facettes. This new group, which emerged around 1995 and included some of the artists associated with Tenq, worked with a form of readymade: the rural village. Some of the Tenq artists, in particular Fodé Camara, had been travelling to the region of Casamance in the south of Senegal. In the village of Hamdalaye they happened to meet a self-taught artist, Maat Mbaye, who was making extraordinary wall paintings. They began to visit the village regularly and set up workshops in the fallow period, when the villagers would have time after the harvest. The Tenq artists received money from a Belgian NGO to fund these workshops.

Later, Huit Facettes were invited to be in documenta11 (2002), where they showed videos documenting scenes of this rural environment, its landscape and animals. I remember going to see Kan-Si, a member of the group, and questioning this representation: ‘Why did you make this film about the village and rural life when actually this project is about you guys from the urban context extending your work to interlocutors in Casamance? Why didn’t you just shoot your debate in a flat in Dakar?’ I felt they were falling into the clichéd representation of the African rural context and development.

NA: And the group’s answer?

CD: Kan-Si didn’t seem concerned, but El Hadji Sy distanced himself from the documenta11 presentation. This time, he didn’t travel to Kassel, with the other members of Huit Facettes. He wasn’t much of a fan of Okwui Enwezor’s approach, and resisted being co-opted into a diasporic discourse on identity politics and race. Sy is of the generation that grew up with Léopold Sédar Senghor and had dealt with these questions early on. What he wanted was infrastructural activity that was not about identity but was a socio-aesthetic movement.

NA: Let’s turn to Ibrahim Mahama. I know you’ve recently returned from a trip to Ghana. I sense some scepticism. Is it because of the contrast to your experience or involvement in the nineties scene? Or is it a wider scepticism related to the art market?

CD: I travelled to Ghana most recently in March 2022, and mainly met artists from a younger generation. The first time I went to Ghana I visited the late, wonderful artist Atta Kwami, who won the Maria Lassnig Prize in 2021 and whose mural is currently on display at the Serpentine Galleries (2022–23). Kwami had an on-off relationship with the Department of Painting at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Kumasi, where he lived. He was too radical for the painting department at the time. Since 2008, a new generation has taken over the Department of Painting and shifted the discourse with the introduction of cultural theory, postcolonialism and critical thought. Mahama emerged out of this new movement.

Airplanes, Red Clay Studios of Ibrahim Mahama, 2022, Tamale, Ghana. Photo: Clémentine Deliss.

The scale of Mahama’s project in Tamale with its multiple hangars and airplanes is so large that I couldn’t help but ask: Who is this for? Tamale is far from Ghana’s capital, Accra, and there isn’t a lot going on there in terms of art practice. If young artists set up studios, and galleries have the courage to open shop in Tamale that could change the landscape and the value of Mahama’s remarkable intervention. His main focus has been on schools, education and exhibitions. Mahama is fascinated by ruins and the leftovers of the recent colonial and socialist past. He is an avid collector and buys large quantities of artefacts from sewing machines to architectural blueprints, textiles, chairs – everything you can imagine. He has basically gazumped any new museum that might be opening in West Africa by having already collected everything related to manufacturing, a sort of a semiotics of the industrial. When I was there in March 2022, his London gallery (White Cube) had not visited the site to witness his extraordinary enterprise. So, it can feel like a mad, lonesome, social project. Still, I think it is admirable. On the level of content. I just wonder about the scale, and whether an artist of thirty-four really needs to exhibit their work as a kind of permanent collection in a quasi-museum.

NA: I find the ambition hugely impressive. But it’s also important to acknowledge that the failures of governmental infrastructures are now more visible than they were in the 1990s and a new generation is addressing the lack of public institutional work. In terms of what you said about this patchwork of people and funding, what is your sense of the team in Tamale and Mahama’s role within it?

CD: There’s a tight team of three, but Mahama has many other people whom he engages. The buildings are incredibly well-built with the finest craftsmanship and design. He had six defunct airplanes freighted to Tamale so that teachers could hold classes about drone technology inside them. One feels he is building, constructing something, and you want to support him as much as possible.

NA: There is a sense of permanence with his work, which is the complete opposite to the idea around Tenq of momentary articulation that is fleeting and time-specific. The contrast between these approaches, separated by thirty years, is stark.

CD: Laboratoire Agit'Art or Tenq would never have wanted to create a museum. El Hadji Sy briefly ran his Écomusée at the Village des Arts around 1998, repurposing several beautiful huts that had been constructed on the site of the Chinese village for an exhibition of Senegalese rural architecture. But that was more of an installation, without museological permanence. If the Laboratoire had imagined a museum, it would have been transgressive, fractured and mnemonic. I don’t believe they were interested in owning and preserving artefacts. That’s what attracted me to the Laboratoire in the first place, that the collective were concerned with non-material presence. As you say, this is quite the opposite of what you find with Mahama’s work. The corpses of the past are contained in this matter that he is trying to preserve, which addresses contemporary questions of restitution, the repatriation of human remains and the formation of new private museums in Africa. Ultimately though, this is the vision of one person, not a collective.

Manifesto of Tenq, 1996, by Clémentine Deliss, As M’Bengue, El Hadji Sy.

Theaster Gates says that artists have the capacity to invent the platform. His Rebuild Foundation also repurposes abandoned buildings to house and care for obsolete or discarded objects associated with Black culture in Chicago, from an archive of house music, to 60,000 glass-lantern slides of art and archaeological history, to a collection of printed matter from the Johnson Publishing Company (publisher of Ebony and Jet). Yet Gates doesn’t speak of archives – he speaks of indexes. He is interested in methodology and process. In a way, he has got much further than Mahama – he is older, of course, but they share something in their approach.

NA: Gates and Mahama adopt very different forms and strategies both from the two contexts in which they work and within the trajectory of artists’ interventionism. Gates has a foundational relationship with music and sonic histories through the extraordinary work of his band, the Black Monks, which, in its essence, is ephemeral, less materially tangible. Mahama’s jets as infrastructures for learning present an entirely different approach. Both, however, offer forms for growing communities and knowledge.

CD: The main question I have about Mahama’s project is around the transparency of its economic structure, something we have witnessed through the extensive modus operandi of ruangrupa at documenta fifteen. If Theaster Gates sells marble chunks extracted from the interior walls of a bank set for demolition for 5,000 US dollars apiece at Art Basel, in order to fund the building’s renovation and transformation into Stony Island Arts Bank, the economics are clear. But with Mahama, you don’t get a true sense of the relationship between him as a highly successful artist in the market, and the institutional, infrastructural work he is doing. And it is that division, that opacity, that I feel is unhelpful in the current context of contemporary art, with these polarised positions. If he is really bridging the gap between institutional art and the market, then let’s see the system.

NA: In this respect, documenta fifteen is significant in its total detachment from the art market. The market is simply not present – neither critiqued nor positioned against – which is undoubtedly a first. Instead, they offer an alternative economy through the lumbung Gallery.

CD: It is timely that we are having this discussion during the period of documenta fifteen. It is the first time for a long time that I thought I could feel something shifting between the market, on the one side, and the institutional art of recurring, biennial-style exhibitions, on the other. Sadly there has been a failure on the part of the art context in which we work to vocally support that effort. What is particularly distressing for me is that the finding committee that brought ruangrupa into the fold of documenta has remained practically inaudible during all the outcries and violent attacks on the ruangrupa collective and its artists. Instead, this summer we heard only from politicians and right-leaning journalists.7 To have such a limited response from the people who are running the established art institutions is deplorable. And so the danger is that such interventionism will go back underground.