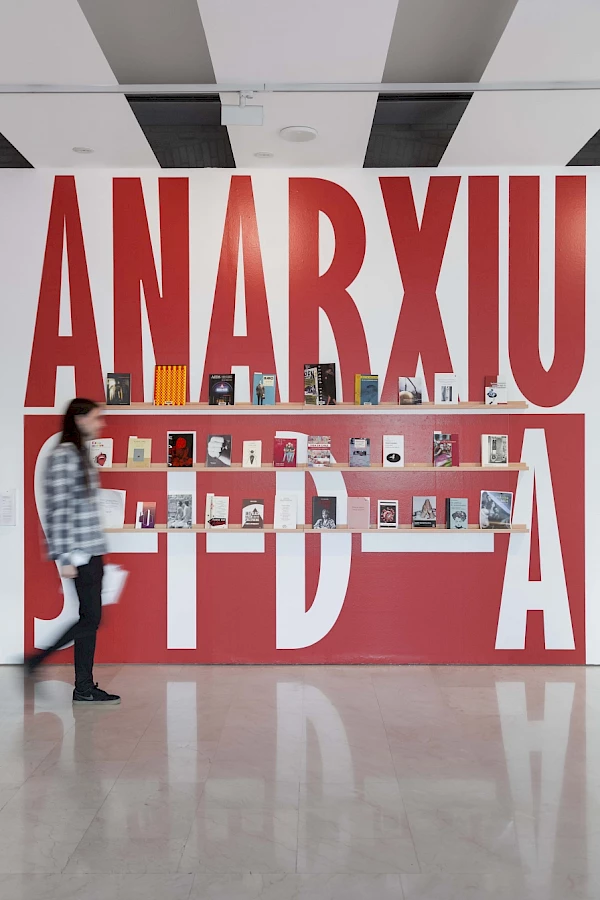

Exhibition view, Anarxiu sida. CED, MACBA, Barcelona, 2018. Collection MACBA. Centro de Estudios y Documentación. Fondo Histórico MACBA. © Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA). Photo: Eva Carasol.

*The title is taken from a lecture given by feminist cultural theoretician Gloria Wekker at Kaaitheater, Brussels, March 2018.

Explaining phenomena like racism and sexism – how they are reproduced, how they keep being reproduced – is not something we can do simply by learning a new language. It is not a difficulty that can be resolved by familiarity or repetition; in fact, familiarity and repetition are the source of difficulty; they are what need to be explained. (Ahmed 2017)

In the late capitalist societies of the Global North, there exists many cultural recuperations of the legacy of the empowering Second Wave feminism and their struggle for the liberation of all women. Establishing legal background for women's rights to abortion, their equal economic status, fighting against the detention of female political prisoners, and demanding equal participation in the political sphere are some of the battlefields that have been recuperated by phenomena such as corporate feminism. Corporate and/ or state feminism is present in many organisations, companies and on the level of entire countries. Its aim is to assure equality without any structural changes, which is one example of the depoliticisation of the legacy of the Second Wave.

Working session at the kick off meeting of Our Many Europes.

Show Me Your Archive And I Will Tell You Who Is In Power, 2017. Installation image of Amandine Gay, Ouvrir La Voix, 2017. Courtesy KIOSK, Ghent. Photo: Tom Callemin.

Femonationalism, on the other hand, is a term that Sara R. Farris proposes for the recent political recuperations and exploitation of feminist themes by ultra-right wing politicians, by neoliberals and also several prominent feminist intellectuals in the stigmatisation of Muslim men under the banner of gender equality across Europe (Farris 2017). More recent recuperation occurred with the #MeToo movement, concerning sexual harrassment and violence against women, especially throughout the various spheres of popular culture, but also in the arts.1 After the movement spread more widely following the public disgrace of Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein, information surfaced that the movement had taken over the name introduced by Tarana Burke, an African-American sexual assault survivor and activist, in 2006.2 Furthermore, as Crystal Feimster puts it, "the #MeToo movement is using some of the same strategies that Black women activists used to mobilize during the anti-lynching movement, which was really an anti-rape campaign for [those] activists".3

Could the method of intersectionality be incorporated as a way of living and looking at the world in daily practices and systems, and not only as theoretical discourses? 'Intersectionality' was coined in 1989 by Kimberlé Crenshaw, professor and theoretician of Black feminism, as the "view that women experience oppression in varying configurations and in varying degrees of intensity. Cultural patterns of oppression are not only interrelated, but are bound together and influenced by the intersectional systems of society. Examples of this include race, gender, class, ability, and ethnicity" (Crenshaw 1989). Today she considers that "intersectionality is a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects".4

This worldview, if we could call it that, had been put forth in the manifesto-pamphlet of a group of feminist activists coming from the African continent and united as the Coordination des femmes noires, in 1978 in Paris: "[Wherever it may be, in France, South Africa, the West Indies...] where we are colonised or put in ghettos, we, Black women, declare that we struggle against all forms of racism, of structural segregations that guarantees murder, against imperialism, patriarchal power, and all practices of torture of our bodies and our thoughts".5

In the documentary film by Françoise Dasques, La Conférence des femmes – Nairobi (1985), Angela Davis talks at the seminal Non Governmental Organizations Forum in Nairobi in 1985, attended by women from NGOs all over the world, about how she defines feminism:

It is a question that could absorb hours and hours of discussion, as we know. As a matter of fact, many women are debating over that very question here at the Forum... In order, truly, to be an activist in a fight for women's equality, we have to recognise that the women are oppressed as women, but we are also oppressed because of our racial and national background, we are also oppressed because of our class background... I think we should join hands across races and across classes, but the specificity of our specific oppression must be recognised and acknowledged.6

In this exceptional one-hour-long documentary commissioned by the Centre audiovisuel Simone de Beauvoir in Paris, we can observe the intense polemics orchestrated by the international NGOs, alongside the official UN Third World Conference on Women in Nairobi, concerning the Palestinian struggle, female genital mutilation, contrasting viewpoints on the significations of veiling a woman's body in Iran, and listening to the speakers of transnational alliances of the LGBTQI communities. These topics were all debated exclusively by women – across races, classes and different sexualities.

Returning to France, it became clear to me some months ago, that some women's thinking in the sphere of culture are far from the thinking within this historical revolutionary moment. A lot of reactions have been published after the opinion column that stated that "men should be free to hit on women" which was co-signed by around one hundred women from the fields of cinema, contemporary art and literature (Catherine Millet and Catherine Deneuve being the ones most frequently quoted). In a response called Can Feminists Speak?7, intellectuals criticised what they considered to be the manipulation of the notion of liberty and technique of delegitimisation of minorities, typically encountered when disqualifying the actions of racialised groups. Art critics Elisabeth Lebovici and Giovanna Zapperi published another response, drawing attention to the dangers of conflating human rights, artistic freedom and freedom understood by the (French White) women who wrote the column (Lebovici & Zapperi 2018).

Many progressive institutions of contemporary art in the Northern and Southern hemispheres with programmes against racism, sexism and homo- and transphobia are struggling to operate structurally. One of them was the Centro Cultural Montehermoso Kulturunea in Vitoria-Gasteiz, that was run by Xabier Arakistain between 2008 and 2011. In 2005 Arakistain launched Manifiesto Arco 2005 demanding that public administrations adopt practical measures to implement equality between the sexes in the field of art. The public institution, the Centro Cultural Montehermoso, was restructured into a pioneering institution for the development and application of feminist policies in the fields of contemporary art. Following the anthropologist Mary Douglas' call to change institutions, and specifically applying the feminist reinterpretation of history of art through Linda Nochlin's seminal text "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" as well as Griselda Pollock's writings8, Arakistain turned Montehermoso into the first centre for contemporary art, culture, and thought to apply the references to art and culture as defined under the equality laws of the Basque Autonomous Community. How could other institutions of contemporary art in the Global North get inspired by intersectional feminist methods?

Self-reflexivity, as a method of questioning who are the public(s) or constituencies which an institution of art is addressing, seems to be extremely apt. How one formulates an address to various communities, on what premises and in what terms in an economy of exchange, these questions can allow an institution to revisit its "broadcasting" channels and the discourses used to present their projects.

Long-term affirmative actions on all levels of the institutional infrastructure – those less and those more exposed to visibility – should be applied. As the documentary film director and sociologist Amandine Gay and author of the 2017 film Ouvrir la Voix, a documentary about the self-representation and self-empowerment of Afro-descendent women living in France and Belgium, mentions: "[Following Frantz Fanon, or Aimé Césaire] one has to be able to have a dialogue about the fact that dehumanisation of the oppressed is comprised of dehumanisation of the oppressor... if men and women question one's own privileges... on one's own scale, then the situation will change...".

Above all, to practice intersectionality these examples propose that one acknowledges that a majority of all art institutions in the Global North are result of a process of coloniality of power9 and racial capitalism, which, as we know well, has been accumulating wealth through the mechanisms of racialisation and dispossession as a result of the centuries-long slave trade and above all, through the "bellies of African women".10

References:

Ahmed, S. 2017, "Introduction. Bringing Feminist Theory Home", Living a Feminist Life, Duke University Press, Durham.

Crenshaw, K. 1989, "Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics", University of Chicago Legal Forum, special issue: Feminism in the Law: Theory, Practice and Criticism, University of Chicago Law School, Chicago.

Farris, Sara R. 2017, In the Name of Women's Rights. The Rise of Femonationalism, Duke University Press, Durham and London.

Lebovici E. and Zapperi, G. 2018, "Miso et maso au pays des «droits de l'homme»", Mediapart, 22 February, viewed 3 May 2018.

Nochlin, L. 1988, "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?", Women, Art and Power and Other Essays, Westview Press, Boulder, CO. The essay was initially published in 1971.

Pollock, G. 1988, Vision and Difference. Feminism, Femininity and Histories of Art, Routledge Classics, New York.

Vergès, F. 2017, Le Ventre des femmes. Capitalisme, racialisation, féminisme, Albin Michel, Paris.