In August 2011, Ugandan artist Rumanzi Canon and I started what I called an "archival platform" for lack of a better term. To express the unfixed nature of history, we called it History In Progress Uganda, or HIP in short. In an attempt to avoid any current affairs, we decided to only engage with documentation of historical moments that are at least two decades old. We looked for collections of photographs in Uganda: in cultural, educational and governmental institutions and in people's homes, including those of photography professionals. Most collections were neglected, covered in dust, mouldy, or partly eaten by insects. We digitised the material simply by photographing the photographs. With permission of the owners, we started to share these photographs online, without any particular selection process, on a daily basis on the HIP Facebook page. We also started to present curated selections of the images in exhibitions and publications that include contemporary responses to historical material.

HIP led to research towards my practice-based PhD, and to me living some considerable time in Uganda. My role is a hybrid one, but in the end, as an artist, I develop forms (in books and exhibitions) to present collections encountered in Uganda and the micro-histories embedded in them to audiences both in and outside Uganda. L'Internationale's request for a contribution to their publication Decolonising the Archive made me trace back the progress made and some of the insights that emerged.

We all have stories about origins that help to understand what and who we are. Media also have histories. Photography has several. One of them tells the story through technology, of people using optical instruments, and an interest and insights into chemistry, adding to what was known about the projection of the world through a lens. Another story considers that painters, developing a photographic gaze, led the way, creating the necessity for the invention of photography. Both stories are set in Europe.

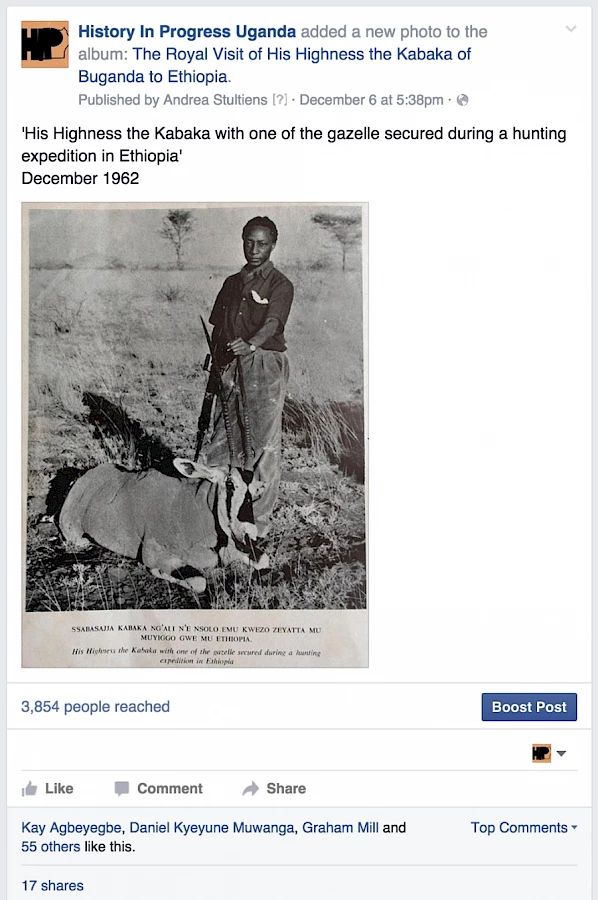

It seems to have taken a couple of decades from the moment of its inception before photography was practiced for the first time in Buganda, the Kingdom in the south central part of the territory now known as Uganda. In the early 1860s, the explorer John Hanning Speke sent his camera back to the coast while he went on to Buganda (Speke 1864, p. X). He met the Kabaka (King) of the Baganda (the people of Buganda) and showed his books with drawings whenever he felt that might be opportune. These were met, here and elsewhere during his explorations, with great interest (Speke 1864, pp. 306–7, 359, 423, 525). Just over a decade later, in the mid-1870s, Speke's colleague Henry Morton Stanley did bring his camera to the court of Buganda. A photograph was made1 of the Kabaka and his chiefs. This photograph is not known in present day Uganda, but other versions of the picture are.

There is little material proof available of a visual culture in Buganda before the middle of the nineteenth century. That does not mean there were no images. If something does not exist, then why have a word for it?

I worked for seven years in Uganda before I became aware of the fact that there is no specific word for photographs in Luganda, the language of the Baganda. The noun ekifananyi, that is related to the verb kufanana (to be similar to), can refer to a painting, a drawing, a photograph or any other two dimensional likeness. I was rather embarrassed it took me so long to work this out, since photographs held a central position in everything I was doing. On a number of occasions, people had brought me paintings when I thought the conversation was about photographs. I had failed to ask the right question.

It is easy to explain this. The official language in Uganda is English. Most people, especially in urban centres, are comfortable speaking it, even if this is a version that is locally known as Uglish. The use of Uglish is a necessity in a country with as many languages practiced within its borders. When I mentioned my "discovery" to Luganda-speaking friends, they shared my wonder since they had never given it much thought and agreed this was an interesting point. When I asked non-Ugandan friends working in the country's cultural sector whether they had noticed something odd happening in the language around images, they all said they had not.

It could be argued that a photograph in Uganda is not the same as a photograph in the Netherlands. There are of course overlaps in the way the photographs function, but they are conceptualised differently. I assume for now that this has to do with the origins of picture-making, materialised images that were initially drawings and then also photographs, in this specific culture.

In 2010, The Kaddu Wasswa Archive was published by three authors: Kaddu Wasswa himself, Arthur C. Kisitu, Kaddu's grandson, and me. Kaddu's face is on the front cover and the back of his head on the rear. The book suggests that the archive is what is in Kaddu Wasswa's head. He creates connections, and makes the documents he kept as well as the photographs he made to prove his activities, readable.

Kaddu was very proud of the result of our work and adopted me into his family. He kept referring to the man on the cover of the book as if he was someone else: as "this man" who was finally given some recognition for everything he had done and tried to do. But as time went by, he also started to share concerns. Achievements that were important to him and his people were omitted from the book. Someone brought to his attention that there was too much emphasis on failures, not finalising studies, not being able to build a clubhouse, not getting a job, not sustaining a business.

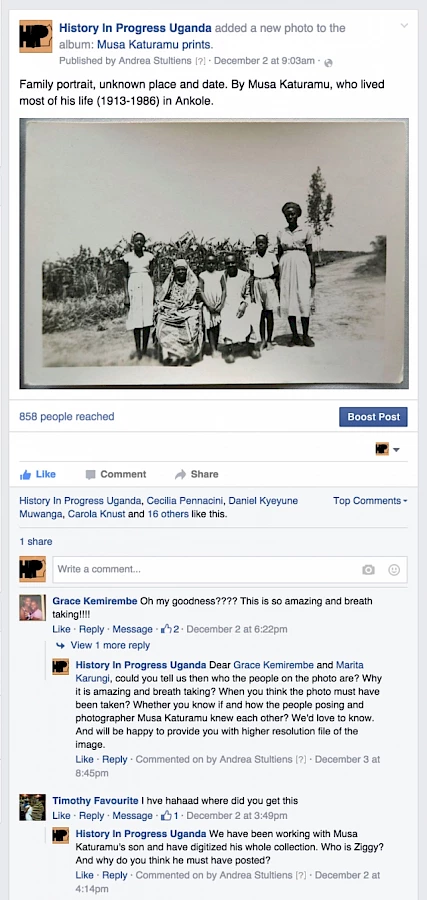

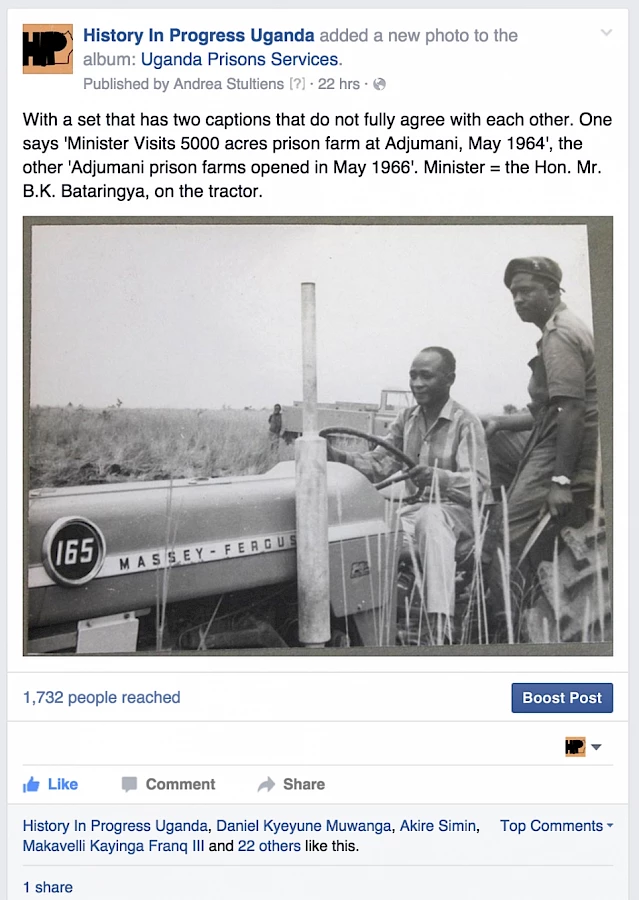

While working with Kaddu and Kisitu, I also came across other collections of photographs. Nobody I met 'knew' what the photographs were about, making it even harder for me to read them than some of Kaddu's photographs. Most of the photographs lacked information concerning who shot what, when and where. The reasons why they had been made seemed to be more obvious. There were events and weddings. There are presidents and other performers. But understanding why the photographs were made does not provide clarity on why I or anyone else should be looking at them.

HIPUganda has a mixed audience following and responding to the images shared. There are those who grew up, and used to live, in Uganda. There are Ugandans, mainly living in the capital city Kampala and other urban centres it seems. And there is a group with general interest in photography and archives. Let me brutally generalise here for a moment, based on observing the responses to photographs shared on the Facebook page. The first group is looking for recognition, to connect their memories to those of others through photographs. The second group is keen to compare pasts and presents, while the third group loves to discover beautiful images that do not necessarily say anything about historical events, but capture aesthetics in a cultural and sometimes historical perspective.

When I started to look for "old photographs", I thought that what is in archives in Uganda, contrarily to what is in the UK for instance, should give insights into all Ugandan society. How naïve (again). Most of the material relates to upper and middle class lives, before or after Uganda's independence in 1962.

The most Frequently Asked Questions when sharing a photograph on the HIP Facebook page used to be along the lines of "why is there no information with the photograph? Who? Where?" I had thought this was obvious. If there is no information, then that does not need to be mentioned. I imagined it gave the person looking at the photograph the chance to be as open as possible. I failed to see that, when a picture is shown without context, it also suggests a gap between HIPUganda who is sharing the photographs, and members of the audience who feel they are supposed to know what they are looking at. The context then is the lack of it, instead of a call to create it together. These questions resulted in a change to our strategy. The lack of knowledge as knowledge in itself is more explicitly added alongside the photographs. The little that is known is indicated, without being afraid that this might limit the freedom of association. HIPUganda and its audiences are co-creators of additions to specific histories at a time when it is no longer necessary, reasonable or acceptable, that pasts be told exclusively from outside or privileged positions.

References:

Kisitu, A.C., Stultiens, A. and Wasswa, K. 2011, The Kaddu Wasswa Archive. A Visual Biography, Post Editions, Rotterdam.

Mitchell, P. and Lane, P. (eds) 2013, The Oxford Handbook of African Archaeology, University Press, Oxford.

Speke, J.H. 1864, Through the Dark Continent, William Blackwood and Sons, second edition, Edinburgh and London.