Interior of the Tropical Museum (Tropenmuseum) in Amsterdam. Courtesy: Karel Kulhavy.

In response to the opposition's criticism of government economic policy in 2006, the then Prime Minister of the Netherlands, Jan-Peter Balkenende, called for a return to the "VOC mentality". This was a reference to the old Dutch trading spirit and entrepreneurialism of the United East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC, 1602–1798/9) – the world's very first multinational company. It unleashed a wave of criticism, since such romanticism about the Dutch Golden Age ignores the inherent historical associations with violence, slavery and colonialism. The Premier later stressed that "it had not been his intention to refer to that at all". However, it was precisely this selective approach to the country's history and his own unawareness of it, that had so offended his critics.

The VOC mentality as a characteristic of the selective historical perspective on the Dutch Golden Age has been a key feature of Dutch cultural policy for many years. The government seized on the economic crisis that broke out in 2008 as an opportunity to make far-reaching cutbacks in the cultural sector, involving such great cuts to subsidies that critics have referred to it ever since as a 'cultural slash-and-burn policy'. Although virtually no part of the cultural sector was spared the effects of the cuts, certain institutions, including Rotterdam's Wereldmuseum and Amsterdam's Tropenmuseum and National Maritime Museum (Scheepvaartmuseum), were particularly badly hit by the policy. It is worth noting that these museums are the custodians of the country's collections of colonial history. The reasons given for the cuts were said to be based on 'impartial economic logic'. The 'success' of museums is determined by the number of visitors they attract. Since critical reflection on the colonial past is hardly a great money-spinner, these museums tend to fall by the wayside. As such, this would appear to be an example of the economic crisis being used to justify an ideological shift of strategy in the nation's cultural institutions. Only the stringent cutbacks, in part masked by urgent calls for cultural entrepreneurship and financial independence, appear to be linked to a renewed insistence on defining Dutch identity and betray a wilful national loss of memory, or at the very least, a disquieting indifference towards some of the darker moments in the country's history.

Opening of the Colonial Institute in Amsterdam. Courtesy: Tropenmuseum, part of the National Museum of World Cultures.

To mark the upcoming millennium, the government had decided in 1999 to donate 100 million Dutch guilders for a complete renovation of Amsterdam's Rijksmuseum: a political gesture that meant that the Dutch population would still have "a leading museum of international standing".1 In 2003, the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (OCW) was reckoning on a budget of 272.5 million euro: by 2009, it emerged that this figure would be exceeded by almost 100 million. But it was all felt to be worth it – in 2013, the New Rijksmuseum was given a grand opening, officiated by Queen Beatrix. However, by this time, the economic crisis was in full swing and the government had announced serious cutbacks in 2010, hitting the cultural sector harder than any other sector, viewed proportionally. The government announced that the 20 million euro subsidy for the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT) was to be halted by the end of 2012. Since Indonesian independence in 1950, this former colonial institute had been a privatised institute for knowledge focusing on medicine and economic development in the tropics and was also home to the Tropenmuseum, a theatre and a library. Despite having a rich collection and history, the KIT was threatened with closure with no chance of a pardon. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which was providing the subsidy, felt unable to justify development aid money being spent on a museum. The government declared that it would only be willing to save the Tropenmuseum if it agreed to merge with two other ethnographic museums – the National Museum for Ethnology (Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde) and the Africa Museum. It was also expected immediately to comply with the revenue model imposed by government and increase its efficiency by merging the management teams. The importance of preserving a huge collection of cultural heritage from colonial history did not appear to be a factor in the debate. Moreover, the government made absolutely no reference to the museum's theatre or even the acclaimed library collection: anything not taken over by third parties was to face destruction.2 This points to the lack of an integrated government policy, since the preservation of heritage became a concern of the museum itself rather than that of government.

As the museum sector responded with horror, the populist/ nationalist Party For Freedom (Partij voor de Vrijheid, PVV) announced its willingness to agree to the closure of the Tropenmuseum. The PVV, which itself was not part of government, but was supporting a minority government made up of the conservative/ liberal People's Party for Freedom (VVD) and the Christian Democrats (CDA) in a confidence-and-supply arrangement, had made something of a name for itself for its controversial populist statements from the sidelines. On this occasion, the party's view was that the Tropenmuseum merely made its visitors feel guilty by spreading "Western self-hatred".3 For his part, the VVD State Secretary for Culture, Halbe Zijlstra, who implemented the cutbacks in the cultural sector, simply confessed to a lack of understanding of the arts: "If you have to make so many cuts, that is more of an advantage than a disadvantage. You need to be able to distance yourself. We want to achieve a major reorganisation of the cultural sector, a culture shift within culture, and that calls for an ability to look at things from an impartial perspective."4 In this case, impartiality meant that every cultural institution needed to earn at least 17.5 percent of its own revenue in order to be eligible for subsidy from 2013 onwards. The advice of the Cultural Council (Raad van Cultuur), the official government advisory body on art, culture and media, to postpone the introduction of the change to give institutions slightly more opportunity to find alternative ways of operating despite the severe cutbacks was dismissed out of hand by Zijlstra. It seemed the cultural slash-and-burn that the Cultural Council was warning about, was not actually a risk, but had in fact been the government's very intention.5

From an ideological perspective, the selective approach adopted in terms of which cultural heritage is worthy of support and which isn't, would appear to exemplify the ideas of the PVV. This radical political party is selective in its view of culture: it presents the ethnic Dutch population, whose "authentic roots" must be protected at all costs, as a minority threatened by immigrants.6 In its 2012 manifesto, the PVV placed particular emphasis on preserving local traditions while art and multiculturalism were dismissed as "left-wing hobbies".7 But it was the first government led by VVD Prime Minister Mark Rutte that was to declare that multiculturalism had failed, through its Minister of the Interior Piet Hein Donner and his 2011 policy document entitled integration, connection, citizenship ("Integratie, binding, burgerschap"). Donner argued that cultural diversity "had primarily led to division and at best to well-meaning mutual disregard".8 In view of this consensus between Rutte's first government and the PVV that held it in power, Zijlstra' minimalist explanation for cultural cutbacks that "the new basic infrastructure will no longer have room for development institutions in the field of cultural diversity" was all that was needed to pull the plug on institutions focusing on exactly that – such as the ethnographic museums.9

From a practical perspective however, it would appear that it was the VVD's focus on economic profitability that informed its selective cultural policy. In 2000, Rotterdam's ethnographic Wereldmuseum was on the verge of bankruptcy as a result of major building renovations and rapidly falling visitor numbers. Even before the economic crisis began to become a factor, the then Mayor of Rotterdam, Ivo Opstelten (VVD), decided to turn the tide by appointing cultural entrepreneur Stanley Bremer. He was given free rein to develop an entrepreneurial policy with a view to making the museum successful again, but more importantly independent of subsidy. Alongside some serious commercial measures including the introduction of a Michelin star restaurant and the hiring out of the museum's auditoria, it was not long before the entire team of curators was dismissed in the wake of the falling revenues and by 2011, as earnings continued to suffer, the radical museum director came up with the idea of selling off part of the collection. Although it clearly breached every museum's ethical code, this controversial move was only prevented by the municipal council after heated discussions in the media.10 Despite extreme attempts to commercialise it, the Wereldmuseum is virtually bankrupt and has seriously undermined its role as a museum in numerous ways. Yet, in spite of repeated signs of wrongdoing, the council (the owner of the collection) has washed its hands of the matter.

Unlike the Wereldmuseum, the National Maritime Museum appeared to have been successful in striking a balance between education and entertainment and thereby becoming less dependent on subsidies. This museum also made quite a radical commitment to cultural entrepreneurship. The museum building's recently-covered inner courtyard was hired out as a means to fund the museum and its presentation transformed from dusty displays to a multimedia experience. Although the Cultural Council expressed concern about the balance between its duties as a museum and its commercial ambitions, it also used the very same document to dismiss any notion of an academic role for the museum. Its research grants – which had until then actually enabled that balance to be achieved – were discontinued by the Ministry. This was followed by a reduction in the government's general museum contribution. Despite having previously received praise, the museum management responded to a serious budget deficit by attempting to dismiss eleven members of staff, including a curator and the senior curator of the academic programme. Although this dismissal attempt was prevented at the last moment, the situation is evidence of a lack of political interest in the museum's programme that was attempting to portray both the glory of overseas trade and the inherent downside of the slave trade.

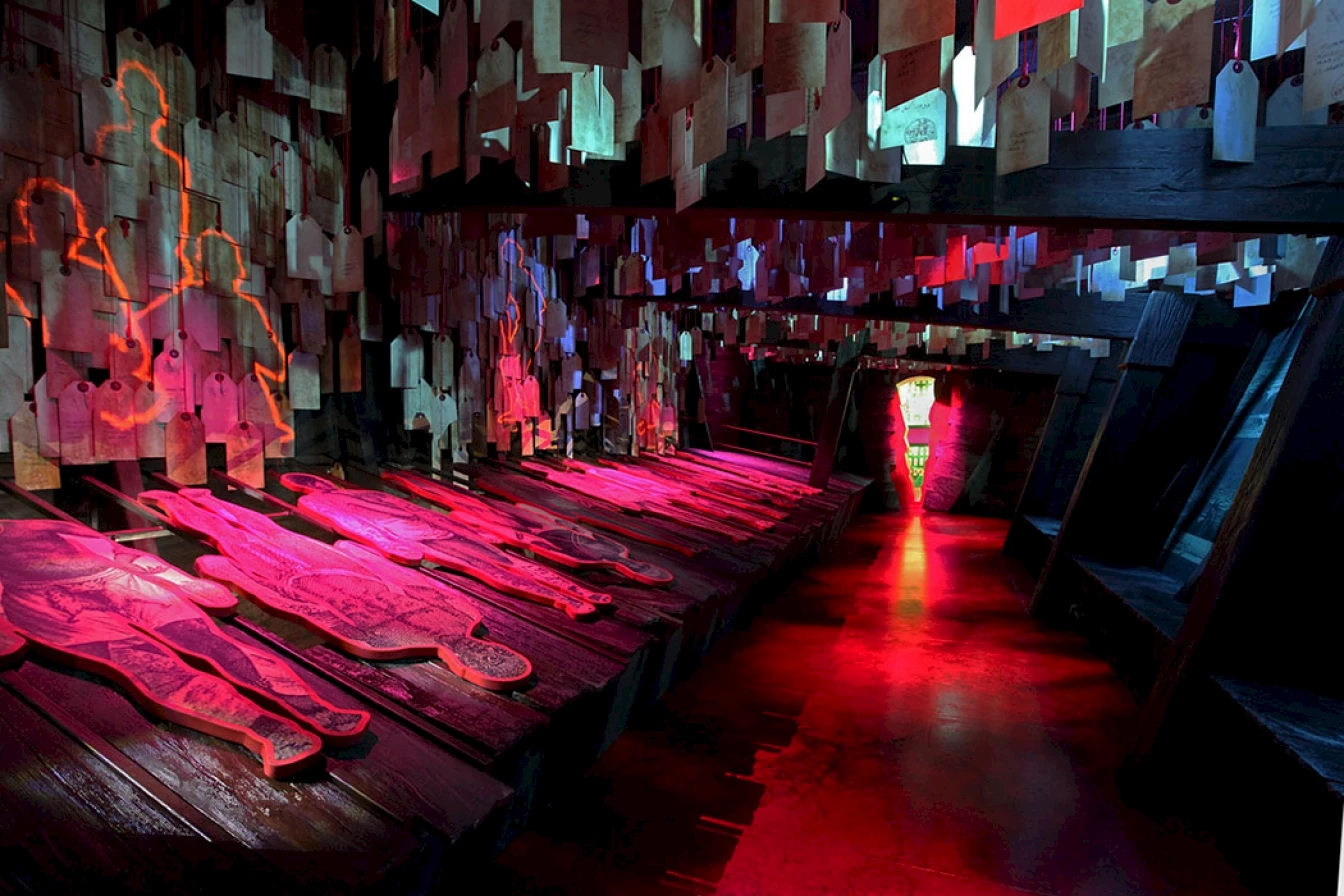

An installation shot of a slavery-exhibition in the Scheepvaartmuseum. The Black Page, The National Maritime Museum, lighting design. Courtesy: Rapenburg Plaza.

By giving an academic role to only a small selection of institutions, the government is undermining the role that museums must play in education. The VVD in particular would appear to see the cultural sector primarily as a leisure industry, whose very survival is measured by the number of visitors it attracts. This means that the principle of museums' financial independence and economic profit is taking precedence over historical value and importance. In other words, culture needs to be able to earn something for the Netherlands. Internationally, Halbe Zijlstra's new cultural policy was primarily based on using art and culture for foreign relations, literally insisting that it contributes to a positive image of the Netherlands by emphasising links between culture, trade and the economy.11 The Dutch Masters of the Golden Age are cited as examples of this. Equally, the reopening of the Rijksmuseum enabled the Dutch Golden Age to put a stop to the negative image of Amsterdam as a city of the red-light district and cannabis cafés. The government prefers to showcase national culture by means of such historic figures as Rembrandt, Vincent van Gogh and even Anne Frank. These are the standard-bearers for museums that have unfailingly been attracting floods of tourists for many years. The aim of cultural tourism and the marketing of a Dutch identity is not only to target other countries, but also to generate a collective sense of an authentic cultural identity within the country itself. The subsidies awarded for national commemorations provide further evidence of an intent to create a selective view of the country's history: the memory of the victims of the Second World War is kept alive by some 4.5 million euro every year, while the organisers of the commemoration of slavery by the National Institute for the Study of Dutch Slavery and Its Legacy (NiNsee) must reapply for a grant every single year, with no certainty that its application will be honoured.12

It simply seems that there is no room for the colonial past in Dutch public discourse. However, until very recently, the world of politics was clearly interested in the country's past and the importance of its citizens' historical understanding. In 2006 politicians Jan Marijnissen (Socialist party, SP) and Maxime Verhagen (CDA) proposed the establishment of a National Historical Museum (NHM) in order to boost the country's knowledge of its history and strengthen national identity. In Britain, Lord Kenneth Baker launched a similar initiative in 2007 for the establishment of a museum of 'Britishness', that should not only focus on the narrative of British history, but above all be a paean to British standards and values.13 Historians and museum professionals in both the Netherlands and Britain were critical of the idea of an historical canon approach, as well as the risk of the museum being used for propaganda purposes, since the project was the brainchild of politicians.14 Whereas the British initiative ultimately came to nothing, in the Netherlands, a management board was appointed and a suitable location sought. However, this ambitious project fell victim to the harsh cutbacks introduced by State Secretary Halbe Zijlstra in 2011, who felt unable to justify a new museum in the wake of cutbacks at existing museums that were, after all, already developing initiatives to showcase Dutch history.15 Although the NHM could potentially have created a more consistent home for the colonial past, both the British and Dutch initiatives were primarily inspired by the notion that multiculturalism had failed and by ongoing discussions about the integration of immigrants, globalisation and increasing public Islamophobia in the wake of 9/11. Rather than suggesting an opportunity for society to engage in some self-reflection, the desire to define a national identity would therefore seem to be rooted in nostalgia.

The Rijksmuseum was opposed to the establishment of the NHM, as it felt that it itself could, after reopening, again fulfil the role of a national historical museum by means of a mixed collection of art and historical artefacts that would offer a chronological narrative of Dutch history. However, this turned out to be heavily based on the more glorious aspects of the country's history.16 The merger of the Tropenmuseum with the Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde and the Africa Museum demanded by the government might have been devised as a counterbalance to place a clearer focus on the Dutch colonial past and historical relations with the 'Other' alongside the Rijksmuseum. Whilst Belgium has just spent 75 million euro on a thorough renovation of its colonial Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, in order, according to its director Guido Gryseels, "to reconcile itself with the past",17 no similar ideas would appear to motivate the world of Dutch politics: the sole priority was to combine these ethnographic institutions in an attempt to cut spending. On top of suggesting a strong focus on economic profitability, this would appear to be a sign of a collective failure to acknowledge the political deeds of the Dutch past. Whereas Germany has this year officially acknowledged as genocide the massacre that took place in its former colony of Namibia between 1904 and 1908,18 the Netherlands continues to describe the violence it applied during what is known as the Police Actions in the Netherlands East Indies (modern Indonesia) merely as "excesses".19 The PhD thesis by Swiss-Dutch historian Rémy Limpach recently revealed extreme violence to be a structural feature.20 By the same token, the Netherlands has never issued an official apology for the slavery in its history. A recently-published advisory report by the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination expressed concern about whether Dutch society's poor understanding of its history with slavery and its colonial past could actually be encouraging the stigmatisation of certain minorities. Several of the UN committee's recommendations explicitly target what it considers to be the Dutch government's overly relaxed attitude with regard to its anti-discrimination policy.21

Nevertheless, the way that the Netherlands deals with its colonial past does not differ radically from that of other European former colonial powers. In Britain, the British Empire and Commonwealth Museum in Bristol met its demise after being unable to attract sufficient visitors despite various successful exhibitions, publications and awards. The museum was devoted to the history of British imperialism and the effects of British colonial rule. Unlike many national museums in Britain, the museum was not publicly funded, but operated as a charity. In late 2007, the museum announced plans to relocate to London. However, it emerged in 2011 that various museum artefacts had been sold without authorisation and were therefore lost, including several that were on loan. In 2012, the museum announced that it was closing its doors and donated its collection to the city of Bristol, leading to the disappearance of the only museum explicitly devoted to British colonial history.22 In France, it was actually the colonial collections themselves that became the subject of a Grand Projet initiated by the then President Jacques Chirac: he had a brand-new museum building specially built for the purpose, Musée du Quai Branly – proudly located just a stone's throw away from the Eiffel Tower. Even if currently in this institute research has a prominent place, threre are also critical points to be made, especially at its early years. To establish the museum, the French government unceremoniously removed the collections from the Musée de l'Homme and the Musée national des Arts d'Afrique et d'Océanie in 2003, only to present them as so-called arts primitifs. Despite protests from museum staff and academics, the contexts of colonial history and anthropology were literally pushed into the margins of the museum, since nothing could be allowed to detract from the aesthetic experience of the object.23 In this case too, a commercial VOC mentality of 'take over and exploit' overrides any attempt at historical understanding.

Relevant link: photoCLEC: Photographs, Colonial Legacy and Museums in Contemporary European Culture