The Uncensored Censors: How We Say 'Appropriation' Now?

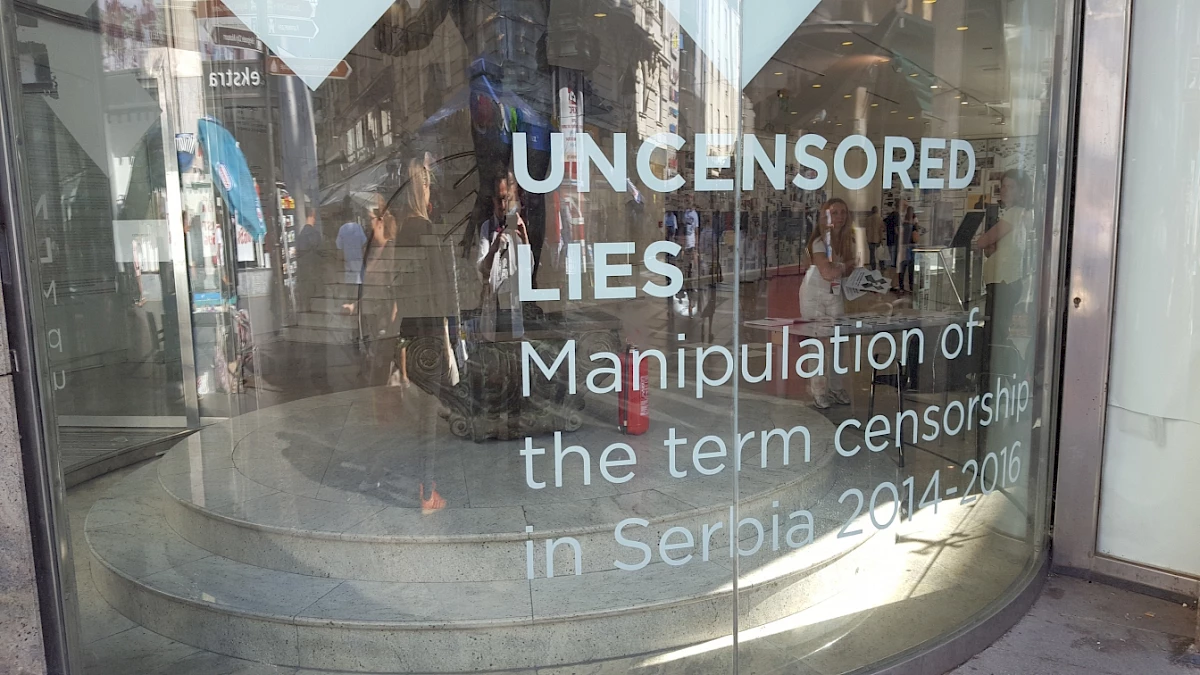

Views of the exhibition Uncensored Lies: Manipulation of the term censorship in Serbia 2014–2016, organised by the Serbian Progressive Party of Prime Minister Vučić, 2016. Courtesy Vlidi.

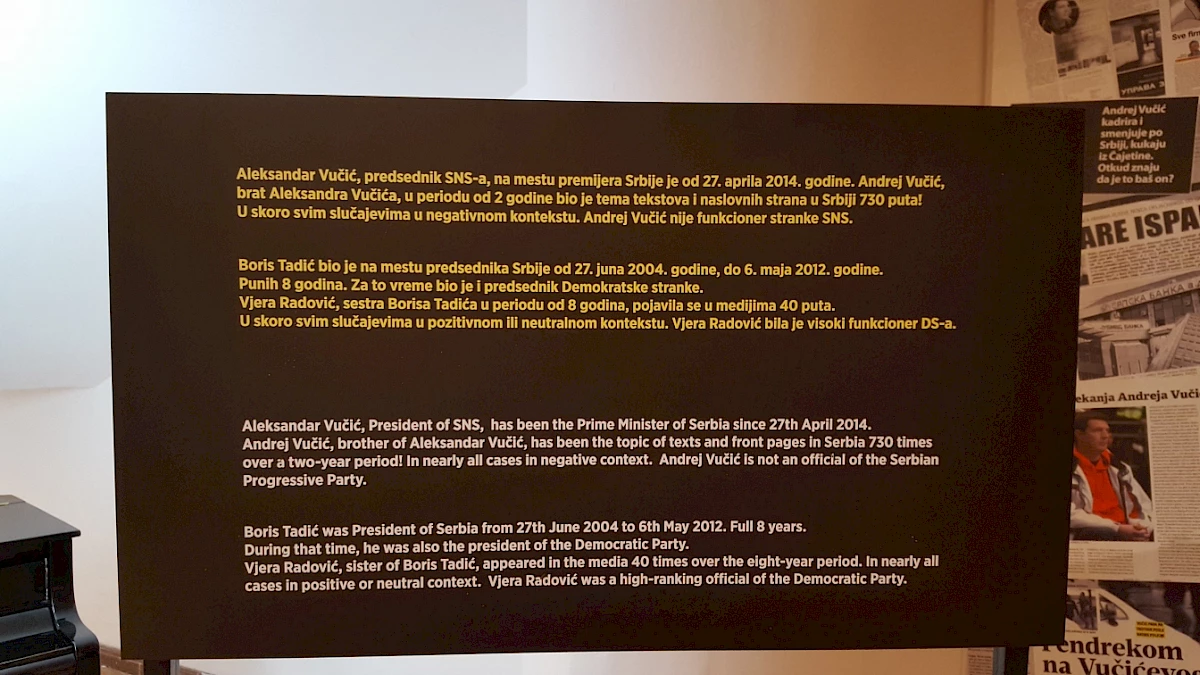

Views of the exhibition Uncensored Lies: Manipulation of the term censorship in Serbia 2014–2016, organised by the Serbian Progressive Party of Prime Minister Vučić, 2016. Courtesy Vlidi.

The citizens say, 'We are oppressed', but the ruler says, 'No, I am oppressed'. For that, we have his word and a Wall of Tweets as proof.

The previous decade was marked by disruptive changes in politics and media, introduced by the perhaps not entirely adequately named 'alt-right'. In such a short time, the ability of alt-right actors to manipulate (social) media grew to receive a somewhat mythical perception. The facts are there: the world's largest economy and biggest nuclear power is seemingly run by the runaway @realDonaldTrump Twitter account; Britain trying (and failing) to leave the EU after a campaign full of blatant misinformation and which no one is taking responsible for; and European politics resembling an endless reality show of neo-fascists vs neo-Nazis, as it has done so for some time now. And this is only the north-west corner of the world.

This text examines an attempt by the alt-right to bring their techniques and technologies to 'old' media, such as the exhibition. It is about the travelling display titled Uncensored Lies, organised in Serbia in 2016 by the then prime-ministerial, now presidential press service of the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS). To make things even more interesting, the progressive indeed regressive1 political entity behind the exhibition was constructed and promoted just before the 2010s – actually, precisely in the decisive 2008 – and a bit before critical analysis invented 'post-truth' and 'alt-facts' as significations to assist thinking about our current situation, characterised by the (global) rise of right-wing sentiment. This would be yet another trace of the certain global (dark) avant-garde practices to historically emerge from the region of the Western Balkans, and especially from the post-Yugoslav space.

Considering how the Party entered politics, the SNS is not exactly a proper alt-right; it is not one of the new players in the political arena of Europe and America after 2008, who act as reality show contestants. This is because its original brand, the Serbian Radical Party (SRS), invented the surreal reality show approach towards politics to begin with: their ideology and political style stems from the 1990s, having its origin in the language and the appearance of the nationalist politicians just post the Yugoslav wars.2 They pioneered the now well-known rhetoric about the 'persistence and suffering of Serbian people' and 'the unjust pressure from abroad'; they have also heralded the division of society to 'real Serbs' (what was toned down a bit to 'honest patriots' after they sovereignly seized power) and 'foreign traitors' (whoever happens to disagree with the Leader). There is not enough space to even list all the reasons (or 'conspiracy theories') produced to explain why their politics in reality brings nothing but fear, depression and despair, despite their 'best' efforts and intentions.

Views of the exhibition Uncensored Lies: Manipulation of the term censorship in Serbia 2014–2016, organised by the Serbian Progressive Party of Prime Minister Vučić, 2016. Courtesy Vlidi.

The Party's Uncensored Lies exhibition was an 'alt-facts-post-truth' reaction of the right wing in power to the public warnings from various actors of civil society and the public sector, including independent and non-regime journalists in Serbia as well as different foreign commentators. All these actors frequently report on the problems of censorship, the harsh polarisation of media content, and the growing media disorientation and proliferation of 'fake news'. At the same time, it is generally held that whatever connects with the Party is best not discussed in public, since everything is now connected with the Party; journalists need to be careful even with commenting on the weather or the current TV shows. The Journalists' Association writes, 'because journalists fear losing their jobs, they agree to abandon professional values. They engage in self-censorship and know which topics to cover in order to avoid conflict with authorities or editorial policies. A number of important topics are never on the agenda, while topics that serve the interests of various centers of power dominate.'3

On behalf of the 'authors of the exhibition' (signed as 'Information Service of the Serbian Progressive Party'), Vladanka Malović, a member of the 'curatorial team' who was the most prominent in communications with the media, states: 'The core task of the media who act as though synchronized by quoting each other was to present [the president] Aleksandar Vučić to the local and foreign public as a brutal censor, who cancels TV shows, closes internet portals, replaces editors and journalists by decree and forbids publishing of [inconvenient] material.' The purpose of the exhibition was 'to show that there is no media censorship in Serbia'. This curatorial thesis was supported by a documentary media collage of texts, tweets, TV shows excerpts and caricatures, in which '[then PM, now president] Vučić and other SNS [SPP] party leaders are referred to in a negative context'.4 The overarching theme of the exhibited material was President Vučić himself, and how harshly and unjustly he is attacked by all the 'free media' – much of which turned out to be personal social media accounts.

The Information Service of the Serbian Progressive Party used the design of a contemporary art exhibition, or more precisely, a surface imitation of the contemporary curatorial research approach, with piles of arty packed, remixed and aestheticised documentary material spread all over the space. They also provided all sorts of statistics about their meticulous work. We learn that the exhibition presents 2,523 examples out of exactly 6,732 pieces of negative media content about Vučić and SNS, published over the two years prior to the exhibition; the fact that the Party demonstrated the ability to track each and every piece of information and every single comment exchanged about their leaders was symptomatic of a certain pathology, but also acted as additional pressure towards anyone considering publicising a critical attitude. The message was clear: 'We watch you everywhere, all the time. We run the National Security Service now.'

Views of the exhibition Uncensored Lies: Manipulation of the term censorship in Serbia 2014–2016, organised by the Serbian Progressive Party of Prime Minister Vučić, 2016. Courtesy Vlidi.

Views of the exhibition Uncensored Lies: Manipulation of the term censorship in Serbia 2014–2016, organised by the Serbian Progressive Party of Prime Minister Vučić, 2016. Courtesy Vlidi.

The Uncensored Lies exhibition was probably the first and only occasion to bring many of its visitors (including myself) to the Progres Gallery – the name of the gallery incidentally relates to the name of the Party. This gallery is otherwise rarely open to contemporary art and experimental curatorial strategies.5 It is rather a place for the nouveau riche, established in the city centre a few decades ago to mark the end of socialist institutionalism. It usually shows truly conservative art, such as figurative painting with mythical, religious, heroic and nationalist symbolism; the kind of painting that fits well with all the marble and stucco, the brass handles and the spirit of petit monumentality provided by the space.

The display of 'media content' covered the period between 2014 and 2016. The vast majority of the content came almost exclusively from the independent media. It included approximately 2,500 cover pages, investigative reports, news columns, social media and comment pieces exposed in the form of a large collage. Much of this material was displayed on movable, didactic 'blackboards' and as huge rolls of printed paper hanging from the ceiling and falling to the gallery floor, suggesting that there is so much more to read, but mercifully leaving enough space for visitors to inspect the content. Frequently represented were the pages and headlines from Danas daily, NIN, Vreme and Newsweek, and, television-wise, the N1 cable channel. The well-known caricatures by Marko Somborac, Dušan Petričić and Predrag Koraksić Corax were also significantly present along with quotes (private and public, official and unofficial) by various media editors, EU politicians, representatives of independent institutions and simply well-known public personalities speaking about censorship in Serbian media. A special position within the exhibition was given to the 'wall of tweets'. This Twitter Wall was not some giant screen, however: the tweets by journalists, representatives of independent institutions or apparently just citizens expressing criticism towards the actual government were printed and displayed in ridiculously blown-up formats.

The scarce video material on show, collected from one critical source which broadcast on cable TV and not online, still managed to fill the whole room with sound. It was a montage, a mash-up of footage from the satirical TV show 24 minutes with Zoran Kesić, presenting probably each and every time the host mentioned the holy name of the 'beloved leader'. The entire space echoed with 'Vučić ... Vučiću ... Vučića ...', as if dozens of channels criticise the prime minister day and night, while he tries so hard to improve the political situation and living standards for Serbia and its people. Such 'post-production art' or arty designed manipulated media enhanced the construed propagandistic meaning of the exhibition: the disembodied voice of the evil 'free journalist' – surely, someone paid from abroad – calls the name of Vučić, haunting him and his supporters like a rowdy but impotent Ghost of Jealousy.

What was excluded from this news overview? It was all but impossible to find any critical (rendered as 'treacherous') media examples from the TV stations with national coverage, the dozen daily newspapers with the largest circulations, or media directly or indirectly financed by public money. In such media, as they ironically write on pescanik.net, 'Vučić remains to be the unquestionable and beloved ruler, a global leader, the job creator, protector and hero, the policeman, an European with a strong Serbian identity, always a trustworthy and credible man'.6

*

How do we call the situation in which the citizens say, 'We are oppressed', but the ruler says 'No, I am oppressed'? For the citizens of Serbia complying to this inverse image of truth, the guilt for the never-ending separation of Serbia from the Arcadian EU should not be directed to the actual government, but precisely to 'the traitors', those who only complain and send such an ugly image of Serbia to the world. And for that, they have the word of their ruler and a Wall of Tweets as proof.

Views of the exhibition Uncensored Lies: Manipulation of the term censorship in Serbia 2014–2016, organised by the Serbian Progressive Party of Prime Minister Vučić, 2016. Courtesy Vlidi.

Views of the exhibition Uncensored Lies: Manipulation of the term censorship in Serbia 2014–2016, organised by the Serbian Progressive Party of Prime Minister Vučić, 2016. Courtesy Vlidi.

The exhibition of Uncensored Lies was unmistakably part of the propaganda machine that still rules Serbia today. It was a form of appropriation and reactionary détournement of the very research apparatus that is the exhibition for the sake of political branding: it turns the original 'claims of truth' into their opposite. The visitors were invited to see the show and to 'decide for themselves' if what they saw implies the presence of media censorship by the ruling party, or au contraire, that the media space in Serbia is not only free and democratic, but saturated with (unjust) criticism towards the government. The passive-aggressive message 'come and see with your own eyes' and 'decide for yourself', as if the exhibition concept is a neutral terrain, was compulsively repeated by all instances of party communication and by the exhibition curators.

In such framing, the claim that there is 'not enough freedom' in public media is replaced by the claim that there is 'too much freedom'. This freedom is apparently being misused to attack the personal and political affairs of one man, President Vučić, who is otherwise doing so much for Serbia and its people. And because of such (naive?) insisting on the act of witnessing, it was simply too tempting not to draw analogies with one of the most appalling acts of exhibition in the twentieth century (or, at least before everything became levelled out), Entartete Kunst,7 organised in Munich in 1936 by the Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels and the painter and politician Adolf Ziegler.8

The exhibited material in both exhibitions was appropriated, or better said 'annexed' from its authors and (re)composed in an exhibitionary complex (as per Tony Bennett) that certainly none of the authors would have chosen for themselves. In the contemporary culture of samples, remixes, copy-pastes, drags and drops and mash-ups, appropriation has become a common, everyday phenomenon. What is inherent to our contemporary understanding of appropriation is the fact that it always recontextualises whatever it borrows from the 'original'. Uncensored Lies, perhaps deliberately or not – hard to say which is the 'lesser evil' here – doesn't show any trace of awareness of this fact.

You, reader, are free to draw your own conclusion from the above.

The name of the Party introduces the strategy of 'inverse appropriation' of the very term of 'progressive'. There is nothing progressive about the politics of a party that champions the rigid and conservative views on politics, culture and economy, mixed with contemporary contempt towards anything intellectual or emancipatory in character. It is the Party which finally managed to unite most politics and public service within an elaborate chain of systemic corruption. Their name is precisely the carrier of the ideology that was retroactively titled 'post-truth', a special instance of a mass disorientation strategy where words frequently – but to make matters worse, not always – mean more or less the opposite of what people could expect them to mean. As said, 'progressive' is just another word that 'followed the fate of words like avant-garde, revolution, modernism, and many others that used to be the building blocks of so-called grand narratives of (mainly) the previous century'. Jelena Vesić and Vladimir Jerić Vlidi, '1984: The Adventures of the Alternative', in The Long 1980s: Constellations of Art, Politics and Identity; A Collection of Microhistories, Valiz/L'Internationale, 2018.

It is hard to find much difference between the politics of the Italian Northern League, Austrian People's Party or the Hungarian Fidesz, placing the SNS/SPP into line with the 'new right' characteristic of post-1989 Europe. Due to their disruptive approach towards the media, it is also hard to tell them apart from the more contemporary phenomena of 'alt-right', such as UKIP or AfD or the Dutch Party for Freedom. This is why 'alt' in 'alt-right' might be a bit misleading. By observing the development of SNS/SPP, we witness the rise of the contemporary right-wing agenda brought to logical and expected consequences; there is nothing unexpected or 'alternative' in such development.

According to the 'Media Sustainability Index' report as published by IREX over the past seventeen years, Serbia received its worst rankings yet in 2018 and in all the fields monitored. According to the report, the only worse ranked countries are Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. See IREX Media Sustainability Index, 2018: irex.org.

Maja Đurić, 'Necenzurisane laži' – Izložba SNS o medijskoj sceni', N1, 18 July 2016, rs.n1info.com. Unless otherwise stated, all translations by the author.

The modest and incomplete archive of Progres Gallery clearly displays the absence of any concept or curatorial policy, except for contingency, populism and propaganda – this is a rental outlet and not an artistic venue of any significance. See progres.rs.

Shown during the Third Reich as a travelling exhibition, Entartete Kunst was a presentation of modern and avant-garde artworks from the first three decades of the twentieth century. It carried the task of proving to the 'common people' that modern art is in essence one sick, anti-German and Judeo-Bolshevism affair. While the Nazis actually confiscated most modern art to enhance their private collections or to sell it to boost their military project, Entertete Kunst served the purpose to shock the population and to make people mock and laugh at the exposed materials.

'We shouldn't be too seduced by the parallels between Goebbel's endeavour and the achievement of the Information Service of SPP. The 1937 exhibition dealt with art and with establishing the cultural hegemony, while "our" rendition is just an uninventively conducted marketing expo created by teams from "creative agencies"; those who turned conceptual art to kitsch a long time ago and ever since the Joseph Kosuth's slogan "Art as idea as idea" was turned into various Saatchi-like "idea campuses", which the young advertising mags drew the very source of dematerialised art from to use as serial material in the post-Fordist economy.' Branko Dimitrijević, "Predlog za eksponat na izložbi Necenzurisane laži" (Proposal for the exhibit at the exhibition Uncensored Lies), Peščanik, 24/07/2016, pescanik.net.