Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

In this conversation academic Rolando Vázquez discusses the notion of decolonial aesthesis with curators Teresa Cos Rebollo and Charles Esche in relation to The Soils Project. The Soils Project, currently on show at Tarrawara Museum of Art, Wurundjeri Country, Australia, is part of the eponymous, long term research initiative involving Tarrawara, the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, Netherlands and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter. A further iteration of the project will open at the Van Abbemuseum in Spring 2024 as part of Museum of the Commons. The conversation was first published by TarraWarra Museum of Art and was edited by Claire Williamson.

Charles Esche: The question of the decolonial obviously came and was born in the conditions of Abya Yala / the Americas. Maybe you could talk a little bit about what happens when it arrives in a settler colony like Australia, which is settled by different cultures, the British rather than the Spanish or Portuguese. How do we discuss this question of decoloniality in the context of Australia? How does decoloniality move from one place to another, and how does it change in the process?

Rolando Vázquez: I think it is important to recognise that decoloniality comes from the history of Abya Yala and from the colonial period that began with Spanish and Portuguese imperialism. That was a period that is distinct from other colonial periods and other forms of colonisation, like, for example, the settler colonialism of the British Empire in Australia. Decoloniality emerges as a thinking from the Global South, grounded in Abya Yala, and provides a non-western vocabulary that allows for different experiences from the Global South to relate to each other. Decoloniality enables conversations that are impossible to have within the dominant vocabulary and epistemic territories of the west.

Here we are not speaking of the languages of Spanish and English, etc., but we are speaking of their logics. Within these imperial grammars, vocabularies and disciplines, the lived experiences of the Global South under oppression cannot be spoken and cannot be thought.

What decoloniality does is to open the possibility of a conversation from and between the experiences of the Global South by enabling an epistemic and aesthetic turn. An important step in this turn is the notion of coloniality conceptualised by Anibal Quijano. Unlike ‘colonialism’, the notion of ‘coloniality’ is not a western term but an analytics that emerges from the South to study and understand the dominant system from the perspective of the oppressed.

Decoloniality, of course, has long roots in authors such as Guaman Poma de Ayala, Fanon and Glissant, but crucially its location of thought is different from the currents of critique of the west (Marx, Foucault, Deleuze, Haraway, etc.). They are looking at the system of power critically but from a western perspective and from within its epistemic and aesthetic territory. Decoloniality, emerging from experiences of the Global South, enables a conversation across other worlds that have been suppressed, offering a vocabulary to speak of the dominant system from the outside and to uncover that there is a plurality of worlds whose existence has been under erasure.

The experience of the María Lugones Decolonial Summer School has been to realise how decolonial epistemology and aesthesis enable relations across oppressions that are disabled or destroyed by the predominance of the relation to the dominant system. When we think of the dominant system in terms of its own vocabulary, concepts and thought, we are still thinking within it. Even when we are strongly against the dominant system we find ourselves bound to it. But we spend little intellectual and political energy to engage in what María Lugones would describe as knowing each other across oppressions.

The decolonial is not about becoming dominant. It’s about creating the possibility of conversation, of learning from each other across oppressions without reducing the difference of every context. This is also the analysis we learn from the political thought of the Zapatistas in Chiapas, Mexico. They say that there is one big ‘NO’ to the world based on universality that has no space for other worlds. One ‘NO’, a common opposition to the system that excludes difference. In its place, they embrace the pluriversal as a response to the one dominant system. What the dominant system did was to reduce difference, to destroy plurality.

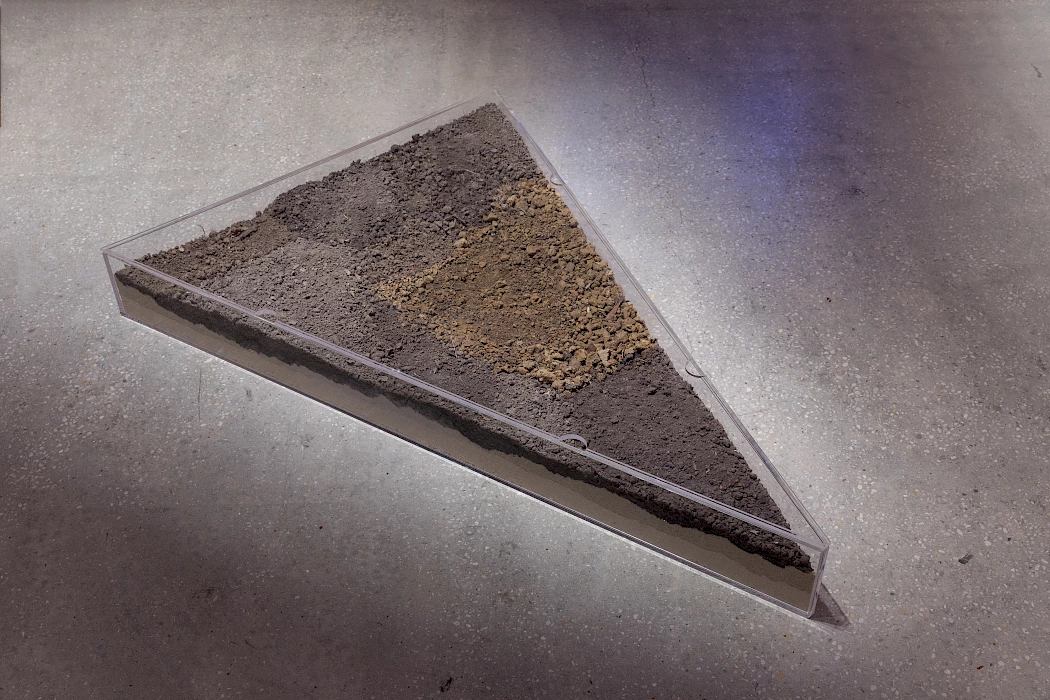

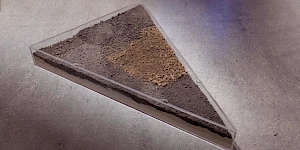

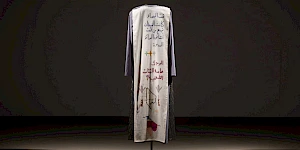

Badan Kajian Pertanahan (BKP), Cultural Acknowledgement of Land Ownership #1, 2023. Installation view, The Soils Project, TarraWarra Museum of Art, 2023. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

Decoloniality doesn’t draw a single response but, rather, enables coalitions against oppression. It says ‘NO’ to the world that has no space for other worlds and enables other worlds to coexist in the pluriversal.

The thinking of decoloniality coming from Latin America has a different route than the postcolonial response to primarily British and French colonialism. Put simply, the postcolonial is an important strategy for opening up and pluralising the notion of modernity so that other histories can fit within it, such as saying that Indian history is also modern history. However, the decolonial does not seek to open the canon of modernity to be inclusive of other ‘modernities’ in that way. Instead, it wants to overcome the notion of modernity that is inseparable from coloniality. The decolonial posture is about going beyond the modern, beyond the contemporary, and not about claiming a place in it or diversifying it.

CE: Speaking from my point of view, it’s fascinating and useful to see what occurs when decolonial theory born in Abya Yala encounters other theories or even ways of being. You talked about the postcolonial, which is part of Australia’s thinking, but I feel the decolonial has the capacity to change the conversation also in Australia or western Europe. Speaking personally, the decolonial gave me a voice in moving away from an old Marxist analysis and starting to listen and learn from conversations that begin south to south but may also take place from south to north. In the context of Australia, which is a settler colony built on genocide and erasure in the most violent way, there is a strange coexistence of north and south consciousness that might be fruitful territory for decolonial thinking.

For the Soils Project, which was born in discussions with Victoria Lynn in Melbourne and expanded through a two-week workshop in Healesville, Victoria, the concept and practice of ‘weaving’ was something we shared, but from different positions. It was introduced by Aldo Ramos from Pluriversity, who brought it from Latin America, and was then picked up by Brooke Wandin, bringing it from an Aboriginal Indigenous context, and Yurni Sadariah, bringing it from Adat (Indigenous/Customary) culture in Sulawesi, Indonesia. In the workshop, ‘weaving’ became a language that could be shared and a technique that encouraged coalition building that in turn led to discussions about what was common and what was different. It seems important that those conversations used a material that western art history marginalises as a craft. What I also find interesting, while admitting a very limited knowledge of the Aboriginal experience, is that the postcolonial idea of inclusion has pushed people to try to establish land rights within the legal structure of the Australian states despite the fact that those legal structures are firmly anchored in colonial power itself. Even the idea of the foundation of the state is something that can only exist within a concept of the colonial. Decoloniality allows us to think about coloniality as a present condition rather than existing solely in the past. It allows a questioning of the trajectory and place where change might happen, and I think it can help build coalitions with activists such as Uncle Bruce Pascoe and Uncle Dave Wandin, both of whom are working to re-establish Aboriginal land knowledges, or Zena Cumpston with her work on the use of indigenous plants. I am still in shock at the way that what you have called colonial ‘arrogant ignorance’ so easily dismissed Aboriginal knowledge of plants and destroyed the agricultural system of pre-invasion Australia. What we see now is that while plants from the northern hemisphere behave in unsustainable and often destructive ways, certainly in the long term, there is still a huge mainstream reluctance in Australia to learn from other epistemologies about their own environment.

D Harding, As I remember it (The Soils Project), 2023. Installation view, The Soils Project, TarraWarra Museum of Art, 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

RV: I think the relation to plants and to the territory you mention is key here. These concepts have been constructed by the imperial imagination for so long. In that sense, I’m quite critical of the free use of speculation and imagination, as if it would always be a good thing. We can think of colonialism as an imperial dream, and if we don’t move out of the enclosure that the imperial imagination produces, we will never overcome the empire, and hence coloniality. With whose dreams are we dreaming?

That is why the critique of aesthetics is so fundamental, because we need to begin asking: With whose imagination are we imagining the world? If we just want to adapt the imperial imagination of ‘landscape’ to the Australian context, or, the reverse, to bring the plants of the colonies to the botanical gardens and world exhibitions in the metropolises of Europe, then that is the imperial imagination expressing itself. In fact, one of the challenges of the exhibitions, both at TarraWarra and Eindhoven, is how to avoid putting plants or habitats into the museum in ways that replicate the imperial imagination of botanical gardens and landscapes. For me it’s key to ask: How can we recover the freedom of dreaming our own dreams?

Here I see the significance of speaking about weaving and how the Pluriversity, Brooke Wandin and Yurni Sadariah can connect through weaving and bypass the disciplinary material language of western aesthetics. This has the potential to respond to what we call the reduction of experience in the logic of modernity. The experience that we often get as aesthetic pleasure in modern western aesthetics and mass media is an experience based on separation from earth, community, ancestrality and cosmological time.

Pluriversity Weavers, installation view, The Soils Project, TarraWarra Museum of Art, 2023. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

What these other aesthesis do, like the weaving that the Pluriversity is bringing from the Iku people of Colombia, is enable other forms of aesthesic experience that construct relations that are based on weaving and on the verbality of the relational. They are not based on the object–subject separation, on the separation between the one who represents and the one who is represented. Weaving disobeys the system of separation and recovers relationality. The dominant subject enjoys privileges but is very poor in terms of relations. It has lost its relation to earth and the communal, to other worlds of meaning, and to ancestral time and the cosmological. Through weaving you can create an encounter of experiences and coalitions that are not possible through the experience of separation of the individual subject, the individual artist of the west.

Teresa Cos Rebollo: I think what you’re saying about weaving can also be said about other practices of relationality that we have in the exhibition. We are seeing how the Adat artists of Indonesia as well as First Nations artists in Australia are using mapping as a way to relate to their territory. These relational maps are created by walking the territory and by creating these relationships with their ancestral lands. The weaving that the Pluriversity brings from the Iku people also follows this same practice of creating relations, as a continuous process. Can you tell us a bit more about how you see mapping? Because it also has a dark side.

Aldo Ramos, Soil is a weaving of memories, 2023. Knitted threads of memories found while walking soils in Petemoro, Mexico, and the swamp at Naardermeer, the Netherlands, with a contribution from Brooke Wandin, dimensions variable. Installation view, The Soils Project, TarraWarra Museum of Art, 2023. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

RV: When looking at the dominant practices of mapping, I first picture what is traditionally a colonial practice where the mapping of territories is done in order to appropriate them. Mapping is a way to classify earth for the appropriation of territory through ownership. What this dominant way of mapping does is impose an idea of space as an abstract category over place, over ancestral territories. The map becomes a representation of space that we could call placeless. It is actually a map that is only possible by being separated from place. It is usually viewed from above, considering the ownership of earth and not a relation to earth. The question is how to subvert that, and how to recover a way of mapping that is not about separation and ownership, that is about placing or emplacing, where place becomes a relation to time, to the ancestral, where a place relates to the communal and gives us the possibility of being positioned in relation, the possibility of recognising that we are in a place, that we inhabit a place instead of owning it.

The view from above of imperial mapping displaces us into abstraction. In one of my articles I speak about the ‘Blue Marble’ photo of the whole earth from the Apollo missions. What that achieved was the total reduction of earth to an object of the abstract gaze that sees itself outside the world.

But the cartographic exercise you are talking about is more like a counter-mapping. It tries to uncover the place, to go against placelessness and oppose the abstraction of a territory as just a measure of property on paper. Instead, it opens the possibility of ‘positioning’—to be in a place that has memory and history and is in relation with other places. Rodolfo Kusch, the Argentinian philosopher, says that people in the deep Americas, the ‘America profunda’, express their way of being in the world as being placed (‘estar’ in Spanish). The modern way of thinking in the world is understanding being as projection, as unplaced or unpositioned (‘ser’ in Spanish).

What I have to emphasise here is the danger of thinking of place only in physical terms, because place is time as well. For ‘Indigenous’ peoples, territory is an ancestral place, not a place in space. It is a place that has a time and that is ancestral. The territory’s memory and ancestrality is where we come from and where we will go back to. Territory is thus not just a physical thing in matter, in materiality. Dominant cartography reduces territory to an object that can be made into a title of ownership. Decolonial aesthesis is about moving from owning to owing, something that becomes clear in the relation to territory and the difference between space and place. Instead of using cartography for owning through the frame of capitalism, we move towards a form of cartography of owing, that is, one that enables us to recognise that we come from a place that is ancestral and that precedes us.

Brooke Wandin and Megan Cope, biiknganjinu ngangudji – see our Country, 2023, and Megan Cope and Keg de Souza, Soil Stories of Coranderrk, 2023. Installation view, The Soils Project, TarraWarra Museum of Art, 2023. Courtesy of the artists / Courtesy of the artist and Milani Gallery, Brisbane. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

CE: The majority of the public who are going to come to TarraWarra or to Eindhoven are white, with their roots in colonial practices. And I wonder how you see the possibilities of communication with that public and what role the cultural field might take in that. There's usually a tendency with art exhibitions that address these questions for a defensive reaction to come from the mainstream art community, the critics or many white visitors. The responses I’ve witnessed often fall either into guilt and self-pity or an aggressive rejection of the subject as ‘politicised’ or ‘not artistic’. But what I feel we are speaking about here is the building of a new relation and, as you said, a new imagination with earth and each other that would benefit everything. How do you see this knot of problems as it relates to the white community and, particularly in Australia, to that extraordinarily displaced community that is entirely a result of colonialism? Do you see ways, from your own experience and your understanding of decoloniality, in which this antagonism could be addressed or produce more constructive relations?

RV: There are many issues here. One is the question: For whom are we doing this work? I think on the one hand, these exhibitions should be for those people who have historically been deprived, and the institutions should respond in the manner of restitution. I also think it’s essential that there are things that should remain opaque for people who are not from those territories. One of the violences of the white gaze, especially in its logic of the exhibitionary format, is to force everything towards transparency—defined in terms of being legible and digestible for that gaze. When things don’t appear as transparent to the white gaze, and are not digestible or consumable, they are rejected because the condition for exhibiting those other worlds is that they must be consumed by the white gaze. This perpetuates epistemic and aesthetic violence and renews the classical anthropological approach of collecting the worlds of others for consumption. We are seeing that decoloniality is being more and more instrumentalised for creating exhibitions that should be consumable for the white gaze.

Upholding the right to opacity, using Glissant’s words, is a serious issue. It is important to understand that there are some things from the Mayan, the Iku or the Wurundjeri that are not for the consumption of the white public. And there are, of course, other aspects that need to be shown, as they are important for those communities as forms of epistemic and aesthetic restitution. This exhibition project must ensure that those communities are not forced to make their material digestible and transparent to a gaze that will not understand it. The right to opacity is an important response to the forced transparency of white institutions and the misuse of the decolonial to uphold the mastery over the diversity of the world.

Moelyono, Tandak Samira, 2023. Synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 190 x 270 cm. Courtesy of the artist.

The other point is that you have a constituency for these museums that is mostly white, and this project should respond to that. Here it is key to position the publics, for example, by speaking about the white gaze and signalling the question: With whose eyes are we looking and through whose eyes are we being made to see? In this way, the publics become conscious of their position in history.

We might encounter white guilt as a reaction. It shows that the publics are suddenly touched by something that shakes who they are or that reveals things of which they are not aware. They then revert to guilt as a way to preserve their focus on their individuality, their single self. Guilt becomes a mechanism to sustain a form of indolence, of indifference towards others by focusing on the self. Instead of opening towards others, and experiencing that humble liberation of being positioned and realising that their privileges are built in relation to the suffering of others, they turn back to their enclosed but dominant self.

Instead of generating guilt, I think it would be wonderful if this type of exhibition could bring across the poverty of the position of whiteness—and it is crucial here that we address and understand whiteness as a social-historical position and not as a racial category. While it might be the most powerful and privileged position in terms of material wealth and political power, it is for sure a very impoverished one. María Lugones and Toni Morrison help us to think of the condition of privilege, particularly of white masculinity, as grounded in a power over others, of making others inferior. It is a subjectivity that manifests itself through the dominant difference vis-a-vis the colonial difference. Whiteness is very impoverished in its experience of the world and its relation to others because it believes the false idea that the individual is self-sufficient. I think once whiteness understands that it lives in an enclosure and in the reduction of experience, it can see the great benefits of engaging with the decolonial and the plural connection to other worlds, of becoming more than a single self. In my pedagogies, I see my white students here in the Netherlands going through a process of humbling and recognition of how their condition of privilege is also one of extreme poverty in terms of being separated from earth, the communal, their own ancestral memories and the cosmological. They then begin to connect to worlds that are still in relation and see the possibility of becoming human in other ways. So I think in the colonial equation or the colonial difference between modernity and coloniality there are no winners. There is dominance and oppression, but the dominant side is a very poor thing that had to be dehumanised in order to become the dominant self. Its condition of indolence and indifference towards the suffering of others enables its own privileges and pleasures.

CE: What has been interesting about The Soils Project for us is the way that we in Eindhoven and at the Van Abbemuseum have started to position ourselves in relation to the place we are in, rather than trying to maintain the universalising space that is the model for the museum. At the same time, I have to say this is one of the hardest things to do because our infrastructures and our imagination are so invested in being placeless and autonomous—we are almost irredeemably modern in that sense. I hope that Soils, even in the title, indicates an attempt to ground ourselves in other ways. I want to add that Victoria Lynn at TarraWarra has been working on this for much longer than us and working to position the Museum in relation to the Aboriginal community in the small town nearby. She was able to ease our relations with communities that are rightly very cautious about the demand for transparency and what they share because it usually led to their removal and erasure. Through TarraWarra, we learnt so much because we could talk and relate on relatively good terms. I hope we can begin a similar process in Eindhoven with Soils, developing dialogues with farmers and citizens who have been neglected in the search for a placeless aesthetics of ‘quality’ and individual genius. This is where, for me, the decolonial becomes a real working tool with which to put theory into practice.

Beyond Walls, REMEMBER THE SOIL: Diasporic Perspectives on Soils, 2023. Lecture-performance with Armando Ello, Jeremy Flohr, Glenda Pattipeilohy and Suzanne Rastovac. Presented at TarraWarra Museum of Art, 20 August 2023. Courtesy of the artists.

Part of the relation to the institution here, however, is also the question of restitution. It is often understood in terms of the material restitution of objects that have been stolen, which is of course legitimate, but I think decoloniality understands it in broader terms. Can you give us your thoughts on restitution?

RV: As you said, restitution has come primarily from the debates around ethnographic collections and the restitution of material heritage. What we have been doing in this last year or so is advocating to go beyond material restitution to address epistemic and aesthetic forms of restitution. A contemporary art museum doesn’t have looted objects because there was a strict separation between the ethnographic and the art museum, but the realisation that I explore in my book Vistas of Modernity is that the whole history of modern and contemporary art is tied to colonial history and has appropriated aesthetic resources from all over the world to create its canons and collections. It has clearly been complicit in the silencing of other aesthesis, other temporalities, while gatekeeping the space for the contemporary. A key example here is what came to be called ‘primitivism’ in modern art.

Colonial violence was not just looting objects but also erasing, silencing and imposing a single mode of representation. So for me the spaces that are supposed to hold the modern or the contemporary must engage in a process of aesthetic and epistemic restitution, in part by transforming the vocabulary and the ways in which we think about what is valid or what is art. I hope that Soils is a small step towards that.

TCR: One thing that Charles and I are thinking about a lot is something we learned from the concept of lumbung and what Ruangrupa very generously brought to western Europe in documenta 15. This idea explores how the ecosystems of sustainability can be shifted from the idea of everything pointing back to the institution, and understanding its job as brute survival and growth, towards a different relation with those places that produce the material that it might want to show, interpret or mediate. How can we sustain or support the sustainability of communities elsewhere upon which we are dependent? Soils very much wants to focus on that.

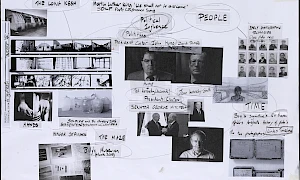

RV: I want to talk about Patricia Kaersenhout’s work Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner Too? and the way an exhibition can have a politics of restitution by connecting local communities and assembling conversations that are integral to this question. The work is a wonderful example of how an intervention in the museum can enable communities to come together—communities that are often dispersed and certainly disregarded by the museum or art world. In addition, I think, speaking of epistemic restitution, the work is about questioning a western canon and how decolonial aesthesis makes possible the emergence of constellations of art histories that have historically been peripheral to the dominant narrative. Epistemic restitution has a lot to do with uncovering those constellations. They don’t need to be invented, they are there, but they are never narrated together and appreciated for the depth of their critique. I would see that uncovering as an act of epistemic restitution as well.

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production

The Studies Center of Museo Reina Sofía will publish an open call for four residencies of artistic practice for projects that address the emergencies and challenges derived from the climate crisis such as food sovereignty, architecture and sustainability, communal practices, diasporas and exiles or ecological and political sustainability, among others.

-

–tranzit.ro

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

–M HKA

The Lives of Animals

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at M HKA that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ is a series of sound installations by Özcan Ertek, Fulya Uçanok, Ömer Sarıgedik, Zeynep Ayşe Hatipoğlu, and Passepartout Duo, presented at Salt in Istanbul.

-

–SALT

Sound of Green

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ at Salt in Istanbul begins on 5 June, World Environment Day, with Özcan Ertek’s installation ‘Sound of Green’.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Open Call: Research Residencies

The Centro de Estudios of Museo Reina Sofía releases its open call for research residencies as part of the climate thread within the Museum of the Commons programme.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

–SALT

The Lives of Animals, Salt Beyoğlu

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at Salt that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Plant(ing) Entanglements

The series of sound installations Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them ends with Fulya Uçanok’s sound installation Plant(ing) Entanglements.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production. Research Residencies

The projects selected in the first call of the Sustainable Art Practice research residencies are A hores d'ara. Experiences and memory of the defense of the Huerta valenciana through its archive by the group of researchers Anaïs Florin, Natalia Castellano and Alba Herrero; and Fundamental Errors by the filmmaker and architect Mauricio Freyre.

-

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

Related contributions and publications

-

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Pollution as a Weapon of War

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimate -

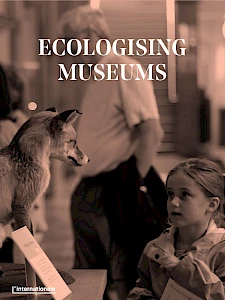

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Pollution as a Weapon of War – a conversation with Svitlana Matviyenko

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Françoise Vergès – Breathing: A Revolutionary Act

Françoise VergèsClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Ana Teixeira Pinto – Fire and Fuel: Energy and Chronopolitical Allegory

Ana Teixeira PintoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Watery Histories – a conversation between artists Katarina Pirak Sikku and Léuli Eshrāghi

Léuli Eshrāghi, Katarina Pirak SikkuClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: The Arrow of Time

Catherine MorlandClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

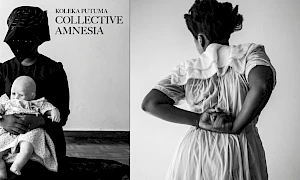

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

Reading list: October School. Reimagining Institutions

October SchoolSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimateMSU Zagreb -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

Algumas coisas que aprendemos: trabalhando com cultura indígena em instituições culturais

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteEN ptLand Relations -

How to Keep On Without Knowing What We Already Know, Or, What Comes After Magic Words and Politics of Salvation

Mônica HoffClimate -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations -

The Object of Value

SlinkoInternationalismsLand Relations