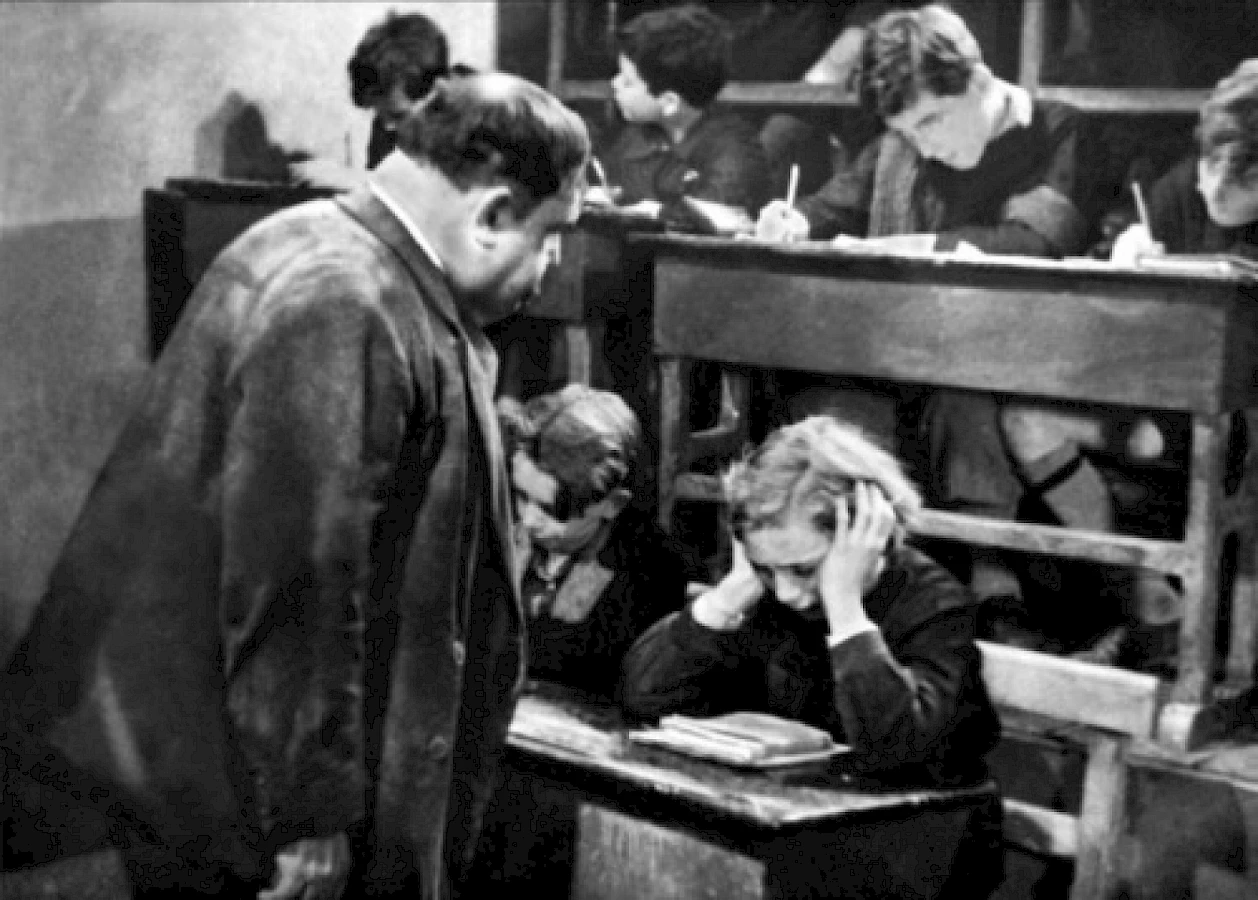

Excerpt from the film Zero for Conduct, 1933.

"My boy, the disciplinary committee has agreed, under pressure from your soft-hearted teacher [...] to excuse your behaviour. Especially as you have spontaneously decided to offered your apologies. Apologies which are worthless unless repeated before your peers. We are waiting. Come now, what do you want to say?" Tabard answers: "Sir, I say bull!" In the next scene, the boys are no longer sitting obediently at their desks but running amok in the dormitory of the boarding school. And Tabard, raising a flag, proclaims: "War is declared! Down with teachers! Down with punishment! Up with revolution!" In this memorable scene from Zéro de conduite (1933), Jean Vigo encapsulates the moment at which a disciplinary system comes up against its point of rebellion.

This second episode begins with a military parade of militiamen, tanks, and weapons of war in Havana. Fidel and Raúl Castro salute the marchers. Behind them, we can make out the poet Nicolás Guillén. The martial images alternate with footage of Susan Sontag speaking in a library: 'Is it the militarisation in Cuba? Maybe that too. If homosexuals in such countries are identified with women, i.e., as weak elements, and the country's ideology is focused on strength, and strength is associated with virility, then male homosexuals are viewed as a subversive element. It's an element that in itself implies that power isn't the only goal of adult life.' Later, when asked about 'the silence of certain left-wing groups', she answers: 'I think one of the left's weaknesses has always been a difficulty in dealing with questions bearing on moral and political aspects of sex. [...] The discovery that homosexuals were being persecuted in Cuba shows, I think, how the Left needs to evolve. It's not just a serious case of injustice that must be exposed, but something that compels people to take note of a lapse in the attitude of the so-called left that goes back a long way.' This interview is part of Conducta impropia (1984), a documentary by Néstor Almendros and Orlando Jiménez Leal about the persecution of homosexuals in Cuba.

A third episode, this time in Ernesto Daranas' film Conducta (2014), takes us back to the classroom, to a primary school in Havana where a meeting is taking place between a teacher, the director, some inspectors and sundry civil servants. The group is discussing whether to send a particular boy to a 'school of conduct', a supposed 're-education' centre for minors with criminal backgrounds or living in situations of extreme social vulnerability. In the fictional film, the teacher, Carmela, defends young Chala, who lives in a highly precarious situation, in the care of an alcoholic mother. Carmela: "The school of conduct will be another mark against him in life. It alienates, whether we like it or not. I was his mother's teacher, I've been his teacher for the last three years, I know him better than any of you." Inspector: "But we can't begin such a serious process and then back down three weeks later." Carmela: "You're thinking about what it will do to your reputation. I'm thinking about what it will do to the boy's reputation." Inspector: "Carmela, you know you are held in great esteem, but there's been a series of problems in your classroom. You have to realise that we can't allow it." Carmela: "Excuse me, but you don't allow anything in my classroom. I started teaching here before you were born." Inspector: "Perhaps that's too long." Carmela: "Not as long as the leaders of this country. Do you think that's too long?"

A similar idea of conduct runs through these three scenes of confrontation with the arbitrariness and violence of disciplinary systems. And we could add a fourth episode: The Cátedra de arte de conducta, which was active in Havana from 2002 to 2009. This educational programme conceived and produced by Tania Bruguera as a project for political and aesthetic change and a space for collective discussion and social action in Cuba takes its name from those very same 'schools of conduct'. But the glossary of the project adapts the definition to its own ends: "In Cuba, institutions which intend to reform or rehabilitate minors with social conduct problems, that is, disability to respect and obey the norms and rules established by the social systems." One of the main fields of work of the programme and its participants was to challenge those rules or laws, testing their margins and blind spots. Many of the works and exhibitions produced as part of Arte de Conducta revolved around barter, the black market, the literal or subversive application of the law, and the activation or disclosure of social relations. Through workshops, debates and exercises, the projects brought into play numerous critical tools for acting in the gap between legality and legitimacy.

The Cátedra de Arte de Conducta officially wound up in 2009, the year in which Tatlin's Whisper #6 infiltrated the Havana Biennial. I like the idea of seeing both projects side by side, with their different temporality but a similar desire to bring about subjective and political change. For Tania, ending the educational programme also meant creating a void that was supposed to generate new desires. When Claire Bishop wrote that "the aim is to produce a space of free speech in opposition to dominant authority (not unlike Freire's aims in Brazil) and to train students not just to make art but to experience and formulate a civil society," she was referring to Arte de Conducta, but we could also read it in relation to Tatlin's Whisper.

Excerpt from the film Zero for Conduct, 1933.

Recently, this space for freedom of speech has been restaged in numerous venues and museums around the world. The action that was censored in Havana in late 2014 has spread to New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Rotterdam, Eindhoven, Paris, Rome, and other cities. In a gesture of solidarity with Tania Bruguera, Danilo Maldonado and all those facing charges for exercising their right to freedom of expression, the organisation Creative Time coordinated a global day of action on 13 April, and it has since proliferated around the world. The contagion effect has not yet reached Cuba, where the government's tight control over information prevents its viral spread through squares and networks. Information is a threat to a system that operates like a kind of autoimmune disease, attacking its own social body rather than protecting it. Nonetheless, as in Zéro de conduite, a disciplinary regime based on fear and punishment can boil over.

Translated from Spanish by Nuria Rodríguez Riestra