An Extended Lecture on Tree Twigs. Toward an Ecology of Aesthetics

Horse chestnut leaf from John Ruskin’s "Lecture on Tree Twigs", 1861.

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1818, oil on canvas, 98.4 x 74.8 cm, Kunsthalle Hamburg, Hamburg.

Here he is. Ecce Homo. Caspar David Friedrich's Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, painted in 1818, is the box cover image for the software of modernity. It is a complex thing; simultaneously a picture of the individual's will to mastery over nature and also his insignificance in the face of it. Wanderer reveals the rift at the heart of the modern era from which we need to escape.

Here we see our mountaintop journeyman, distinct from the world below, defining himself apart from nature and the messy quotidian world beneath the clouds. His back is turned to us, although he is possibly with us or even is us. He faces the horizon and looks longingly to an imagined future that is pictured in his mind alone. This is the artist as super-seer, sovereign genius and truth seeker; taking us to places we otherwise would not imagine to go. This is the artist avant-garde at the start of a journey into the unknown, leading us with hope into the perfect light.

Friedrich's painting is the introduction into modern romantic art history, a history presented as an unfolding, sequential development of form and ideas operating, for the most part, in parallel to the day to day world of politics and economics, albeit indexed to the historical context, but all the while distanced from it, above it—a witness to it, a critic of it, but never an accomplice.

Unknown artist, Portrait of Immanuel Kant, 18th century.

The software engineer behind this packaging is Immanuel Kant. Through the dual architecture of purposeless purpose and the disinterested spectator he transformed art into a bespoke aesthetic system, operating in an autonomous zone that reflects the world from a safe distance, a beautiful thought experiment which gave privilege to the eye above all else, and a tool that would be complicit in separating man from nature, art from daily life, for the next two hundred years.

As the nineteenth century progressed, art under this Kantian model was increasingly framed by the triangulation of artist-spectator-connoisseur and, combined with a rising capitalist, industrial economy and the withering away of religion, this architecture rose to form the twin temples of the art market and the museum. This ensured that art was maintained in a privileged system of representation, reflection, and consumption in opposition to the pre-modern concept of art as the enhanced utility and ritual of human activity (and the objects thereof now rendered obsolete in the museum itself).

Now we find ourselves at the tail end of the modern era, the twin edifices of market and museum look increasingly precarious within the unraveling of economics and politics in our late technological age. On a local level the public support of an art world that is by self-definition 'useless' and autonomous is faltering. The best claims for art now are made to us in terms of regenerative economics, numbers of hotel 'bed nights' sold, added value, our compliance in an attention industry, but increasingly this is less convincing as it becomes clear the true beneficiaries are somewhere else, not in our neighbourhood.

That art has found itself marooned in this way is for the most part a consequence of the compartmentalization of the arts initiated by the age of industry and capital. 'High index' user groups within our society have shaped art to their best advantage to create cultural capital and generate wealth. The market-driven spectacle economies of our major museums, whilst consumed widely, ultimately serve the highest percentiles. Elsewhere other arts, such as craft, architecture, and design have followed other trajectories, as we know 'demoted' to popular, folk, amateur, or functional arts. At various moments these arts (once referred to as low art) are absorbed into the higher index economy, but predominately at the behest of those higher up the food chain.

The bifurcation between High and Low is now apparently a thing of the past, but this has merely been replaced with a far more nuanced system of control, approval, and consensus commensurate with the complexities of the market. What not so long ago was termed High Art has mutated but maintained a trajectory away from common usership, continuing to serve the interests of its main stakeholders—although we might now describe it as cool, critically engaged, or important art.

This case is of course most acute in the world of the fine arts, which has become the one most removed from ordinary use (in part a requirement for its index of commercial value). For example, regardless of who controls the system, most people know how to regularly use music, film, or architecture in a way that most would not consider applicable to art. We can happily understand that we can use music to stimulate a mood or to dance to it within the ritualized behaviours of our culture, as part of the way we live, at a wedding or on New Year's Eve. The static gallery exhibition, art installation, or performance is not accommodated into our regular life patterns in the same way, though it can be done. This would certainly mark out an individual as a culture vulture of a particular metropolitan bent. Its forms are constructed by a highly refined set of users, who for reasons of money and power have a keen interest in not allowing contemporary art to become too popular.

Subsequently art has drifted away from being commonly understood as something of social value; the wider populace have embraced art or rather applied artfulness in other ways such as gaming, programming, gardening, craft, selfies, Taylor Swift fandom, and creating content for YouTube. It is noticeable that these forms of art shift more toward the spectrum of prosumerism, making, and usership, where meaning is generated collectively, whilst still operating within a wider market.

There is a sense that something quite different is beginning to happen, as the economic system that has supported autonomous art for so long appears to be collapsing, or at least under threat with the increasing division between the haves and the have-nots becoming vocalized. The cracks are also showing in the walls of public art museums. These museums are not valued enough by the majority and as the cuts come they are first in line. The sector makes its claims on economic grounds: regeneration, visitor attraction, added value, but it is not enough. An art embedded in all our lives, in consistent usership, would survive much better.

The compartmentalization of culture, division of labour and society, has brought us seemingly to the verge of annihilation: economic, political, and ecological. It is in such times of high anxiety that we call upon the idea of history to console us, but also to find tools and stories that help us to think of a way out.

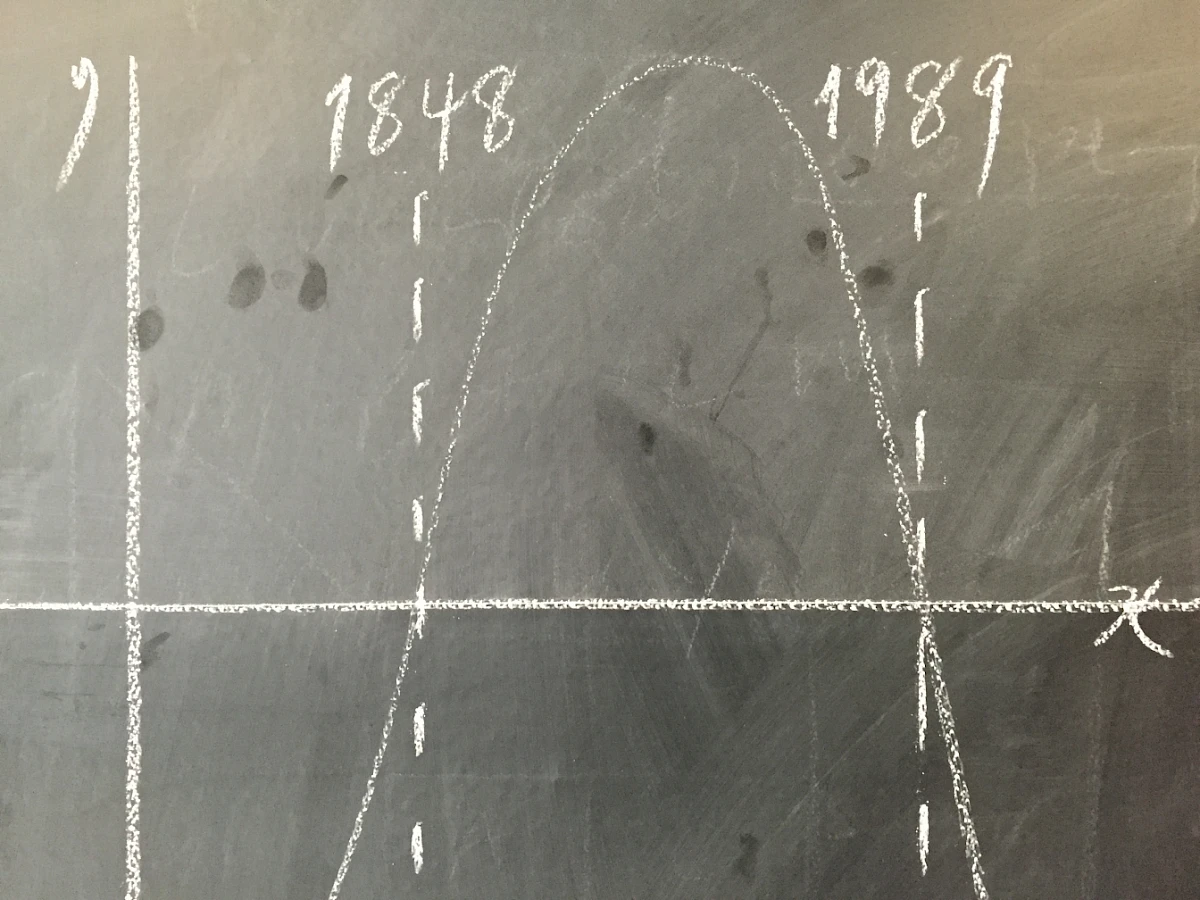

Graph showing a positive parabolic curve intersected by the x axis at 1848 and 1989.

Let us picture a parabolic curve to represent modernity, in which the x-axis shows an unfolding linear time (or for that matter universal space-time) and the y-axis an index of power, certainty, and perhaps wealth. The curve rises from the start of the nineteenth century and descends toward a point we now occupy. We could draw a horizontal line across that intersects the rising curve firstly at the European revolutions of 1848 and meeting the falling curve in the year 1989, the moment the iron curtain falls, free market capitalism wins the day, the Internet begins to weave itself into our lives and very softly, the beginning of the 2008 crash is born. Its apex would sit somewhere around the time between Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907), Einstein's Theory of Relativity, and the end of the First World War.

If we describe ourselves now on the tail end of the parabola, in some kind of transition between waves, somewhere in decline or somewhere before an uncertain something else, what is the narrative we construct to steer us through? What if we were to suspend the idea of linear, one-directional history and go back to Friedrich and 1818, look again around us, look under the clouds and on the ground, what would we find and what other routes could we discover?

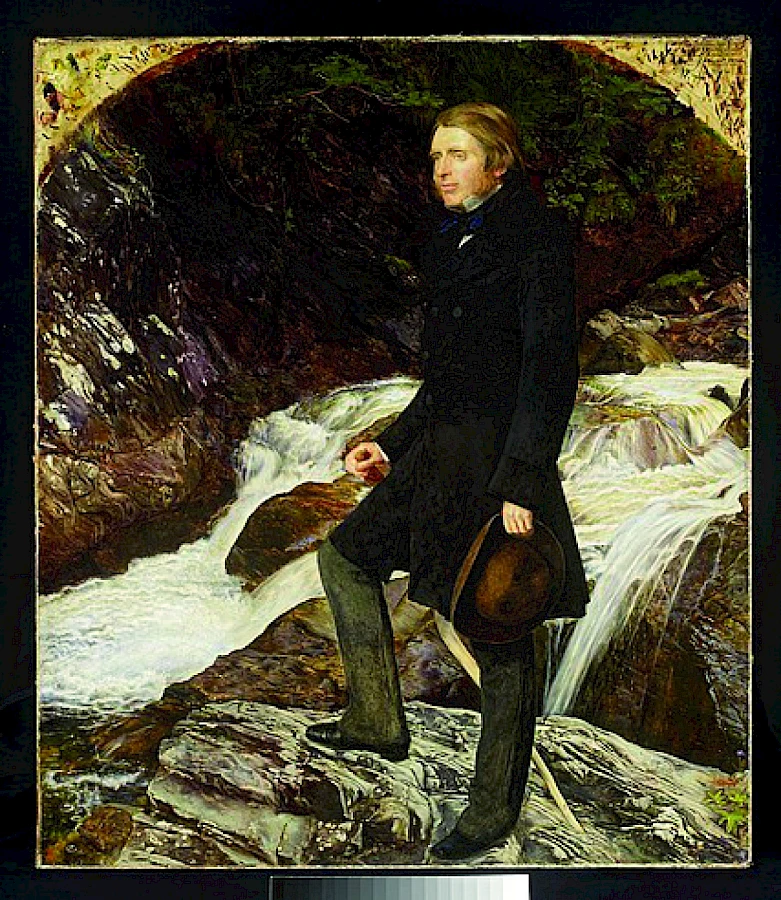

Sir John Everett Millais, John Ruskin, 1853, 78.7 x 68 cm, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, Oxford.

John Ruskin was born in London in 1819, the year after Friedrich painted the Wanderer. Ruskin is an awkward character; his complexity, contrariness, and contradiction don't sit well with the single, linear story of art we have inherited. He appears more often as a kind of phantom or a series of cameo appearances: the eccentric and troubled critic who promoted Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites.

Growing up against the backdrop of the Machinery Question (the Industrial Revolution) Ruskin was the principle voice of conscience, calling for the humanizing of society through art and natural ecology.

Self-described as both Conservative and Communist (the curious movement of Anglican Socialism can be reserved for another day) he was prolific as a writer, artist, and social reformer, railing against the systematization and efficiency of society through the economic, social, and technological machinery of the industrialists. Unable to be constrained as simply a commentator on art, he gained wider fame for his fervent public critique against the inhumanity of the age in voluminous publications and highly performative public lectures. (Interestingly, as one of the first genuine celebrities of the modern age, his housekeeper would later sell his image rights for branded goods, souvenirs, and books.)

His vision was not the fashionable quest for an ideal future constantly remade by systematic growth, capital, and individual success, but a humanity based in living artfully, cooperatively, sustainably, and truthfully within an ecology of perpetual change. As such he insists we must understand art, not as an end in itself, but as process, the manner of work undertaken—as a tool to effect social, physical, and spiritual betterment. Throughout his life his work took him away from the limited field of art discourse, building a holistic view of the world in writing and also through teaching, action, lectures, social projects, painting, agriculture, architecture, and craft. In hindsight it isn't too hard to think of him as the world's first social practitioner.

His influence is still felt across our age within the best intentions of modernity, the moments when we have pushed art beyond the museum into traction with the world, inspiring the Arts and Crafts Movement, with all the twists and turns of its legacy from farming communes, the Toynbee Settlement to Frank Lloyd Wright and the Bauhaus. He established farms, education programmes, conservation projects, and instigated political and social reform. Through his texts and public lectures his influence is felt through education for all, the Labour Party, environmentalism, equal rights for women, the minimum wage, The National Trust, Welfare State, the preservation of Venice, Gandhi, and Rudolf Steiner.

Underpinning Ruskin's work is his holistic vision of culture as nature. Learning to see nature in all its truth was a first principle of a moral life, rather than succumbing to the idealized and perfect forms of the post-Renaissance. This is the bedrock of this vision and the study of geology, flora and fauna, mountains, waterfalls and rivers—their constant variation and 'imperfection' is essential to constructing a humane and honest society. It is a scheme in which man and his actions do not operate above and beyond the natural world, but within it, contingent on it, subject to the same laws and conditions.

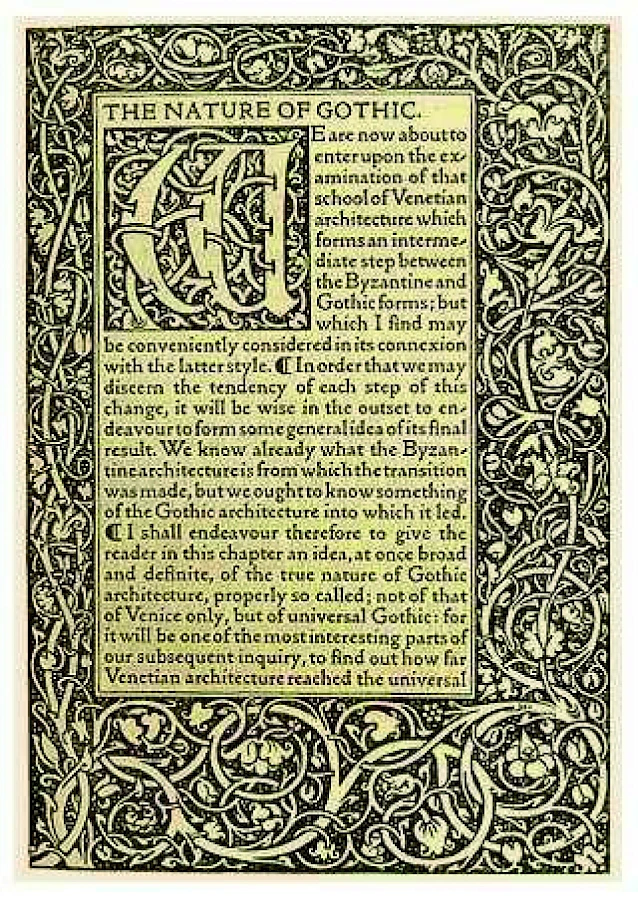

Portfolio illustration from John Ruskin’s The Stones of Venice (1851–1853).

From 1851 to 1853 Ruskin published The Stones of Venice, his three-volume treatise on Venetian art and architecture as a commentary on society and labour conditions. Here he discusses the Byzantine, Gothic, and Renaissance periods as a parable of decline. Against the prevailing trend for building our civic architecture, homes, engine houses, and factories in the logical and mechanical forms of the Renaissance, Ruskin championed the highly unfashionable medieval Gothic, for its natural variations, ethical craftsmanship, and social conditions that supported it. In the chapter "The Nature of Gothic" he forces the point home:

"We want one man to be always thinking, and another to be always working, and we call one a gentleman, and the other an operative; whereas the workman ought often to be thinking, and the thinker often to be working, and both should be gentlemen, in the best sense. As it is, we make both ungentle, the one envying, the other despising, his brother; and the mass of society is made up of morbid thinkers and miserable workers. Now it is only by labour that thought can be made healthy, and only by thought that labour can be made happy, and the two cannot be separated with impunity."

Stones of Venice presented for the first time a complete view on the relation between art and life as a perpetual and necessary struggle with human imperfection."We may expect that the first two elements of good architecture should be expressive of some real truths. The confession of Imperfection and the confession of the Desire of Change."

You could not summarize the modern dilemma more succinctly than this. As we dream of a perfect world within reach through technological progress, this turns to out to be a dystopia that drives change anew.

His vision presents a critique of capitalist society's ambition to resolve human imperfection through standardized production and government. However, Ruskin suggests that instead of worrying about a predetermined outcome we should focus on the process, aesthetics, and ethics by which we live and this will shape our society through responsive organic design as it grows and mutates. In this way we must live life artfully and experience our work not as toil for reward, but as an inherent part of a total social and ecological system of life and work.

In the Arts and Crafts Movement Ruskin envisioned such a system, yet inevitably the prevailing impetuousness and social conditioning of the market system meant that the movement was ultimately coopted into the emerging consumer lifestyle, exemplified by William Morris's ultimate fate as producer of luxury goods, rather than becoming an effective agent of reform.

The Coniston Mechanics Institute and Literary Society, c. 1872.

We can contrast the development of an industrialized cultural machinery with Ruskin's persistent but somewhat flawed attempts to create genuine alternatives to those on offer. These include his education programme for Winnington school for girls, museums for the working classes, road building projects for his Fine Art students at Oxford University, and the agrarian communes of the Guild of St George. In the Lake District village of Coniston, where he resided from 1871 until his death in 1900, he encouraged the development of the local mining and farming community around the Coniston Mechanics Institute as a hybrid centre for community, art, and education.

The Mechanics Institute movement was created to support the rapid technological expansion of Britain. It was to teach the workforce in the new emerging technologies, sciences and arts, toward building innovation, creativity, growth, and a healthier more contented population.

The institutes were conceived as both instrumental and altruistic. Whilst driving the nation forward as a global superpower through education, skills, cooperation, and entrepreneurship, they inadvertently created the crucible for true democracy: instigating voting rights for workers, unionization, equal rights for women, education for all, etc. The institute movement can be cited as the reason the United Kingdom avoided revolution, because this education for all instilled the belief that they could bring progressive change through their own evolution of the system from within.

By 1850 there were over 700 institutes in Britain with equivalent numbers in the United States and the Commonwealth Nations. In Ruskin's own Coniston Institute he shaped local culture according to his philosophy of art as living: a combination of hand, heart, and head. The institute had a community bath house, library, assembly hall, kitchens, collections of art, and artifacts (for educational use not spectatorship) and workshops which hosted Home Craft Industries—an Arts and Crafts school for miners, farmers, and their families who learned through making, drawing, wood carving, metal work, and lace. Products of the school were humble, competent, not especially refined but 'good enough.' This created an internal sustainable economy for the village to supplement and enhance their labour on the farms and in the mines. In contrast to the publicized success of the Arts and Crafts, this was a truer reflection of Ruskin's philosophy: working in ordinary life for ordinary people, as a fellowship, as part of the ebb and flow of daily living and learning.

Ruskin became an increasingly popular performer in the 1850s, filling halls with up to 2000 people on national lecture tours. He frequently used them to goad and provoke the industrialists and politicians running the Victorian empirical machine. For example a lecture on cloud forms in painting could easily descend into a vitriolic attack on the greed of the mill owners and the pollution of the skies.

Subjects were pointed. More often his talks were like sermons: performative and illustrated with props and numbered lecture diagrams drawn by himself, the artists, and his household. These were thrown around the stage in the manner of a wayward nineteenth-century PowerPoint.

In 1861 Ruskin was invited to give one of the prestigious lectures at the Royal Institution, the great theatre of science where luminaries such as Michael Faraday, Humphry Davy, and Henry Cavendish had presented their discoveries to the world.

However, on this occasion Ruskin chose to present on the apparently more humble subject of tree twigs. To the slight bemusement of such a refined audience, he proceeded to give an account of the growth of trees and their leaves, and in particular drawing attention to the unfolding development of the horse chestnut tree, describing in detail the extent to which each individual leaf in its individuality and imperfection, none the less finds its way to full growth in relation to a cohesive whole, in the interests of the complete tree.

The theme of the night is elaborated in greater detail in the chapter "On Leaf Beauty" in the earlier pages of Modern Painters (1843–1860). Here on this night the real point is simply made: that man, his actions, and arts are not predetermined, universal, manufactured, and perfect, but an inherent part of a perpetual system subject to continual changes within the prevailing conditions, part of, and in dialogue with, the total ecology of nature. In this scheme the arts (including technology), are not distinct from nature, but a process intertwined within the very fabric of the universe.

In a wider context Ruskin speaks extensively about how to acquire, and how to employ art only for social effect, arguing that England had forgotten that true wealth is virtue, and consequently art is an index of society's wellbeing. As such individuals have a responsibility to consume wisely, stimulating beneficent demand. Economics is not simply fiscal, but in its original sense 'good housekeeping' and governance of the natural and cultural ecology over which we have custody. In this way we can look again at Ruskin as the first true environmentalist and a principle voice to untie the binds of spectatorship and division.

Exhibition 'Museum of Arte Útil', Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, 2013.

Arte Útil has become a quasi-movement that incorporates the group Asociación de Arte Útil initiated by artist Tania Bruguera. It has convened a growing international network of people who have the ambition to reintegrate art into society, away from an artist-centred, market-oriented paradigm, into an effectual manifestation of creative collectivity. This is a proposal of art beyond pictorial representation that works in the world, as part of the nature of the world, on a 1:1 scale. This, as Bruguera states, is art as a verb.

My involvement in this constellation of activity came through developing projects at Grizedale Arts in the English Lake District village of Coniston, where, serendipitously, Ruskin lived out the last thirty years of his life. The art projects conceived there came through a desire to reassert the idea of the artist as contributory citizen, working beyond the confines of the art world (Coniston is a place, like most, where the Art World has no currency) and to work in ordinary life, in this small rural community. Here we worked with artists and non-artists to make not art, but things more artful, to respond to the needs and urgencies of our fellow residents. The aim was not to give artists the freedom and space for individual expression, but contrarily utilize artistic competencies to the needs of our constituency. The results included a community shop, the restoration of the Coniston Institute, the annual harvest festival in the church, a new cricket pavilion, a farm, making cheese, running the Youth Club, a new public library—employing art processes to enhance daily life, rather than taking art from the autonomous realm and translating it into life. The results, for the most part not recognizable as 'art,' were welcomed by our community because they could be valued for what they did, what they contributed to conditions on the ground in tangible, useful ways. In the development of this way of working it became clear that the art did not lie in any particular object or thing, but in the way processes (a shop, festival, library, etc.) were changed by the application of artists' thinking. The key was how artfully something was done, rather than whether it was art or not.

This work drew us into working relationships with likeminded souls such as Bruguera, writer Stephen Wright, and the team at the Van Abbemuseum, all of us striving to escape the architecture of a system that was increasingly failing to take part in the evolution of society and merely looking to preserve the status quo, repeatedly, emptily acting out the rituals of the radical: 'Zombie Modernism.'

On the back of these conversations the criteria of arte útil were honed and used as a measure by which to asses projects that could be accessioned into the archive and Museum of Arte Útil—a repository of over 500 case studies that includes social enterprises, schools, therapy rooms, tools for illegal migrants, bullet-proof skin, and housing projects.

The common criticism of useful art or arte útil (or even arte utile as proposed by Pino Poggi in Italy in the 1960s) is that it is subservient to a neoliberal agenda, or even 'not art'—simply providing the services traditionally supplied by the state and now being withdrawn within a framework of a right wing ideology.

John Ruskin, Rough Sketch of Tree Growth: Macugnaga, 1872, pen and ink, watercolour and body colour over graphite on pale grey wove paper, 22.8 x 16.6 cm, Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, Oxford.

However, we could argue this view is mistaken on the grounds that arte útil comes from the ground up, creatively responding to urgencies within constituencies, more often as an anarchic critique of unfavourable social conditions. Furthermore it might be more strongly argued that nothing kowtows to the neoliberal agenda more than the idea of individual creative expression, reinforcing the sovereign artist, cut free of any moral obligations to operate within the complex ecology of our day to day grind.

At the same time this negative critique of arte útil also reinforces the system of division engineered two hundred years earlier that serves the market so well, polarizing positions into them and us, art and not art.

A more productive critique could be that arte útil in its current form is still quite divisive, separating art projects that are 'useful' from those that are not. For me one of the key propositions that comes out of the Lexicon of Usership is that we can be liberated from the idea that art is simply a set of things in the world defined by the triangulate of artist, connoisseur, and spectator and move toward a more accurate and universal concept of art as way of doing something, in which we can talk of the degree to which something is art, rather whether it is art or not, art as coefficient not designated form.

Such a way of thinking where art is defined as a process implicit in all human activity, to one degree or another (yet still at times creates art products) would subsequently allow us to reintegrate useful and useless, high and low art, neo-conceptualism with folk art, music and architecture, sculpture and craft. It would be a holistic system operating in four dimensions, where the degree to which something is art would be dependent on a complex of multiple factors, which we could visualize as vectors between multiple points within the matrix of all activity. Therefore Kew, the Shangahi Yu Garden and seed bombing could all be described as arts, in relation to traditions of gardening, but occupy quite different coordinates within the frame, albeit within the interconnected system we inhabit.

Criticisms of arte útil have also exposed the difficulty that many have had with the idea of the word use, which in itself has been misused with its negative implications. However, (as language clearly illustrates that meaning is created by use) this is a word that should be reclaimed, reused as, at present, the best positive term to articulate a way of thinking art anew.

If arte útil can only exist in isolation, or as a counter to the mainstream romantic conception of art, it limits its chances of a wholesale impact that would reintegrate and reclaim the value of art for broad society—and of course maintain the danger that it could be re-captured by the market system as a movement alongside Futurism, Constructivism, and Pop—also movements that strove like many to bring art back into life.

Therefore to negate this, it seems a vital project to conceive a holistic theory of art that would accommodate both arte útil and the post-Kantian history we have inherited. This would mean a recalibration of 'aesthetics' as a complete system of transformation, no longer an idealized autonomous system based on the fallacy of dis-interested spectatorship, and transform it into an integral part of our way of living founded in the reality of interests behind every action and thought in nature.

John Ruskin, Kingfisher, c. 1870–1871, pencil, ink, watercolour and gouache, 25.8 x 21.8 cm, Tate Britain, London.

In such a rather bewildering and expansive conception we can also engage with the proposition that all art is, and has always been, useful to someone somewhere—even Kant himself provided the break clause of purposeless purpose, to acknowledge the necessity of function. Clearly the world of art before the market and industrialized production was one embedded in ritual, craft, design, architecture, and enhancement. But we can also articulate a matrix of usership around even the most traditional autonomous objects. This would include, for example, the manipulation of Abstract Expressionism in Cold War politics, museum education programmes to substantiate public value and funding, to the sensory stimulation and association triggered by the forms of a Mondrian or Morris. There are constellations of users around any given art process or object, which offer benefits in varying degrees. Even in a museum the broader usership encompasses the staff, the Friends Association, the school groups, the lovers' meeting, the aesthete or connoisseur, to the drug user who furtively finds his way to the top floor bathroom. To date it has been the wealthy who know how to use art best: for social status, wealth management, demonstration of power. Equally at other points in the ecosystem we might look at other forms of art as mechanisms to gain sociopolitical effect: graffiti art, union banners, amateur water colours. Indeed we could go way beyond the plastic arts to include music, theatre, cinema, horticulture, cooking, and in fact all human activity as constructions of interconnecting uses and users.

Portrait of Saint Bonaventure (1221–1274).

Confessions of the Imperfect was the companion exhibition to the Museum of Arte Útil held at the Van Abbemuseum one year later. Taking its title from Ruskin's Stone's of Venice, the ambition was to begin to articulate a wider vision of aesthetics as part of an alternative history of art, from Ruskin and the French Revolution to the Arab Spring. It presented a story of the use value of art, its application as a tool for social change and the ensuing network of organic, chance relationships laced through our present understanding of modern times.

In asserting a history of use value it also acknowledged the primary intention of many modernists to change the world, whilst proposing that these intentions have been downplayed by the dominant narrative of artistic form and content. Here we could say the emphasis is not on autonomy, but on the degree to which we can apply art to our day to day life processes, the degree to which something is artful: its coefficient of art.

Horace Vernet, Barricade on the rue Soufflot on 24 June 1848, 1848.

As articulated earlier our inherited understanding of aesthetics is firmly rooted in the German philosophical tradition at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, creating the conceptual framework that sought to detach art from the animal instincts of self-interest. However, a reevaluation of the subject would inevitably go back through pre-modernity to times when art was more or less synonymous with general 'human activity' and 'technology' (techne in Ancient Greek).

A key text in this story is On the Reduction of the Arts to Theology written by Saint Bonaventure in the thirteenth century. Although composed as a text to propose a path to a greater understanding of God, it may also be reread as a path to an understanding of the world through the senses. In it he presents a schema in which the arts, that is human action, is always situated in an ordered system of 'lights', a matrix of sensory perception, process, and action, and in which art encompasses a complete spectrum of human activity, from seeing as an act itself, through to politics to armour making: "Every mechanical art is intended for man's consolation or for his comfort; its purpose, therefore, is to banish either sorrow or want; it either benefits or delights."

Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin rides a horse during his vacation outside the town of Kyzyl in Southern Siberia on August 3, 2009. AFP PHOTO/RIA-NOVOSTI/ALEXEY DRUZHININ/ADDITIONAL CROP VERSION.

Here is a view of the world that positions all human activity within an aesthetic regime, in which all actions, decisions, perceptions are contained within the flow of sensory data, and in which aesthetics now becomes the field of operation and transformation.

Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (MIMA), Middlesbrough.

Related contributions and publications

-

Back to the Future. Confessions of the Imperfect: 1848 - 1989 - Today

John Byrne -

What's the Use. Constellations of Art, History, and Knowledge

-

Autonomy Cube

Nick Aikens, Trevor Paglen -

Use, Knowledge, Art, and History. A Conversation between Charles Esche and Manuel Borja-Villel

Charles Esche, Manuel Borja-Villel