Architectural Dissonances/Dissonant Architectures – Editorial Introduction

Laércio Redondo, video stills, Façade, video projection on plexiglass screen, 3 min, loop, 2014.

Laércio Redondo, Le Corbusier 1936, cast bronze, approx. 4 x 180 cm, 2014. Photo: Mario Grisolli.

Born of the Enlightenment, modernity was built on the values of reason, progress, growth and science. But its self-presentation as universal and transparent has been, and must continue to be, challenged; the product, too, of the intertwined forces of capitalism, slavery and empire, modernity has a ‘darker side’.1 Decolonial arguments show how the narrative of modernity works to impose the rhetoric of ‘salvation’ (through civilisation, progress, development, growth) and the logic of (resource) extraction upon peoples and lands. And the rhetoric of salvation is what makes the logic of extraction possible. Whether justifying colonization because it brings the salvation of civilisation, or modernization because it brings the salvation of progress; positing development as salvation in the era of decolonization after World War II, growth as the salvation of market-based democracy, or neoliberalism as salvation after the Cold War, the persuasive discourse of salvation continues to have multiple coexistent designs within the current rhetoric of modernity.2

In the 2019 essay ‘From Welfare to Warfare: Exploring the Militarization of the Swedish Suburb’, Irene Molina, a professor of Social and Economic Geography at Uppsala University, foregrounds the process by which the stigmatised Swedish suburbs, largely framed via racialised representations of criminality, violence and vulnerability, have been militarised through the Million Programme (Miljonprogrammet). The Million Programme was realised through the modernist project of Swedish functionalism, an integral component of the Swedish welfare state. Molina traces how the Million Programme operates within the rhetoric of salvation and the logic of resource extraction to effect gentrification and leverage sites of market speculation and investment. As such, the colonial continuum makes itself present.

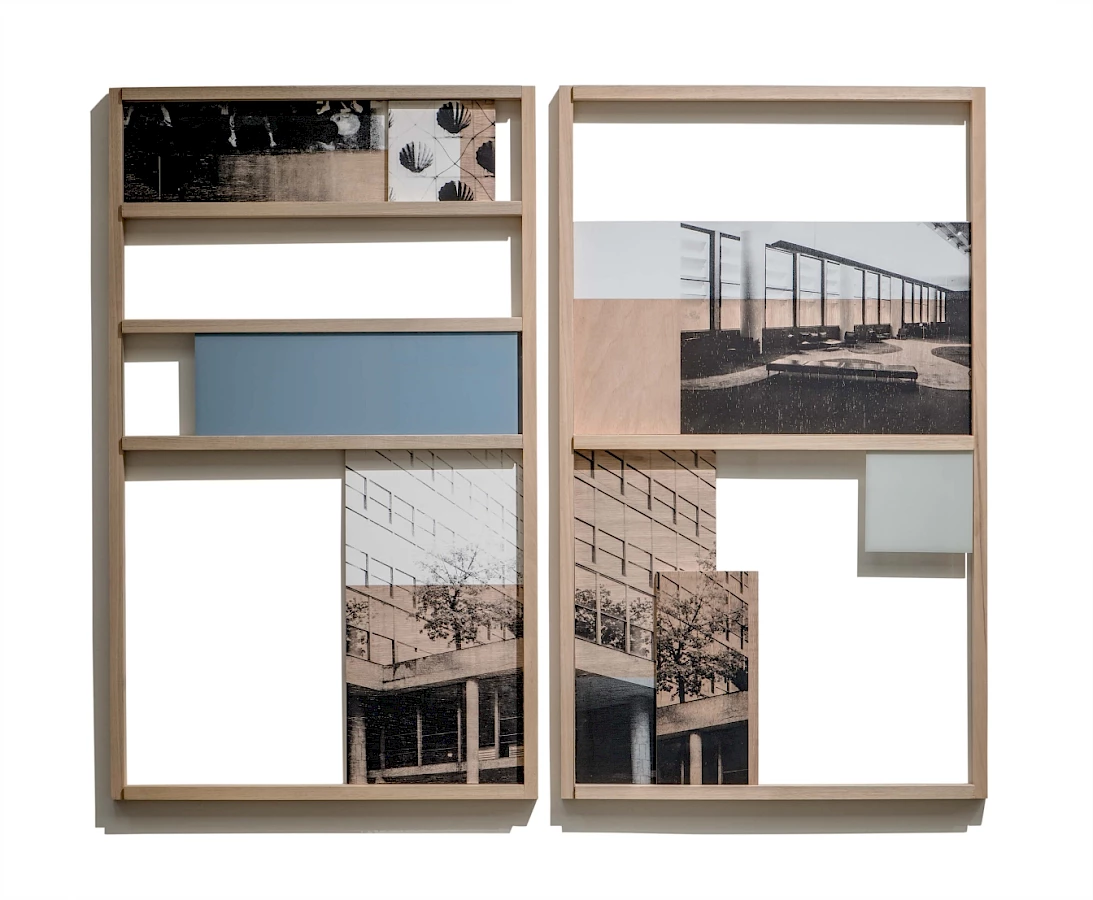

Laércio Redondo, These Times (MEC/D.N.E. 1937–1957), silk-screen on plywood, approx. 245 x 190 cm, 2014. Photo: Mario Grisolli.

Drawing on the work of Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Molina observes how, via the logic of colonization, control and surveillance are normalised in these neighbourhoods, and how this supports a culture of impunity.3 She demonstrates how these processes of militarisation may be seen to work in tandem with colonial practices, processes, technologies and assemblages of securitisation at various socio-spatial scales to create a prevailing environment of distrust, fear and suspicion and a lack of belief in the institutional legitimacy of state institutions, producing and reproducing spatial, racial and socio-economic segregation as a consequence. Moreover, Molina shows how it is in this built environment that the colonial continuum makes itself present, and how architecture itself – as discipline, practice and discourse – operates as the critical domain where colonial violence is produced and perpetuated.

As the legitimacy of cultural and state institutions is increasingly called into question, it becomes urgent to examine not only architectural but also artistic and cultural practices more generally. These institutions have, over time, produced, upheld and made possible the operations of the rhetoric of salvation and the logic of extraction, in the name of the rational, transparent, civic and scientific values of modernity and the nation state. Culture is the terrain where our societies’ norms, values, beliefs and habits are reproduced: the cultural institution is therefore a crucial site for interrogation.

Laércio Redondo, Façade, diptych, 100 x 60 cm each. Monotype/wood, plywood, glass and silk-screen, 2014. Photo: Mario Grisolli.

Over the past few years, art institutions and institutions of higher learning across the globe have begun the important task of confronting their own colonial legacies and are trying to make their organisations better reflect the diversity and multiplicity of voices that have been excluded for so long. However, it is important that in the process they should also reflect on the institution’s own ‘culture of practice’, which may sometimes go to replicate colonial behaviours and attitudes. Institutions must decentre Eurocentric views and not just include, but also give value to those narratives that have been ‘othered’ until now. It is not just about inviting Indigenous and other marginalised peoples into the institutions – the institutions must also seek to reimagine themselves entirely.

For us at Decolonizing Architecture + L’Internationale Online, this means reflecting on the ways we are embedded within institutions of higher learning in art and architecture as well as on the ways we engage with, and relate to, other cultural institutions; our cultural practices and modes of thinking and being. This publication offers some reflections on, and interrogations of, some of the connections and relations between modernism and colonialism, and speculates on some possible approaches to architectural demodernization.

Laércio Redondo, Façade, 100 x 60 cm each. Monotype/wood, plywood, glass and silk-screen, 2014. Photo: Mario Grisolli.

One question that emerges is how society itself might be reimagined through spatial practice – beyond the universalist constraints conceived within modern architecture and projected into a distant utopian future. At the core of modernism lay the idea that the world had to be fundamentally rethought. Focusing on elements of daily life such as housing, furniture, domestic goods and other key cultural forms, modern architects set out to reinvent them for a new century. But modernity exists within a binary relation that involves the erasure, disqualification and degradation of other approaches and world views. Decolonial approaches seek pluralities of transformation of everyday life, occurring day by day.

The demodernizing task for us, then, involves not only imagining other modes and forms of architectural and artistic practice, but also reflectively recovering and foregrounding modes and forms of thinking, being and doing, which have been erased, forgotten and devalued, with reference and reverence to that which came before – as nothing is ever ‘new’.

Laércio Redondo, Façade, 100 x 60 cm each. Monotype/wood, plywood, glass and silk-screen, 2014. Photo: Mario Grisolli.