Art as Action

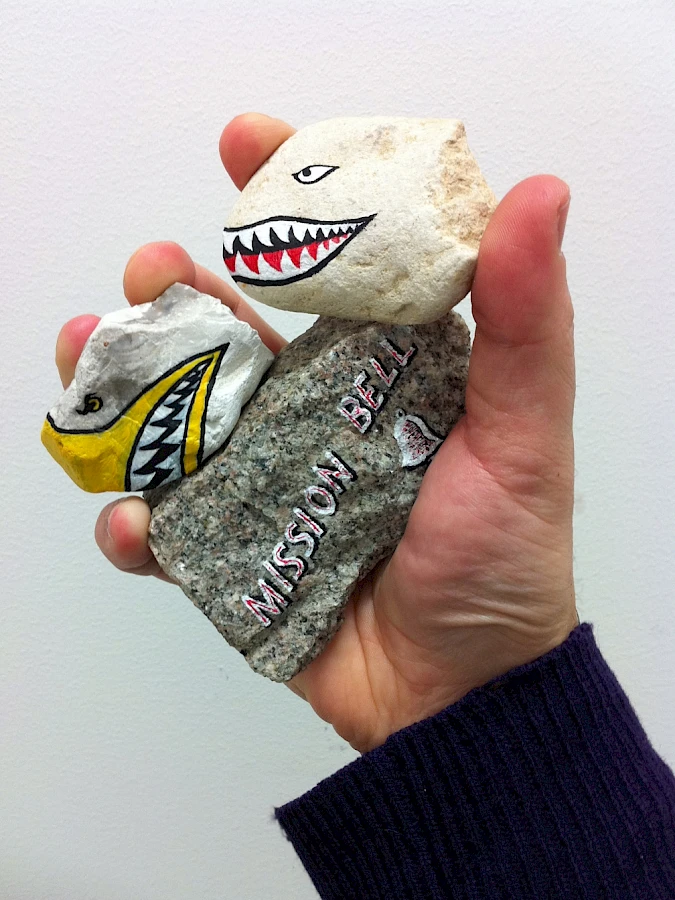

Ahmet Öğüt, Stones to Throw, 2011. Installation, mail and public art project; painted stones, plinths, photographs, FedEx bills. Locations: Lisbon and streets of Diyarbakir. Courtesy of the artist.

An exhibition entitled Art as a Verb at Monash University Museum of Art recently considered the many ways in which contemporary art is engaged with action. The exhibition presented the opportunity to reflect on a set of verbs that have arisen in the context of the protests surrounding the 19th Biennale of Sydney in 2014: 'act', 'boycott', 'withdraw', 'protest'. We will argue that as the distinctions between art, action and activism become increasingly intermingled and complex, these terms can be seen in renewed ways. A verb typically requires a subject and an object – it represents a relational position within a sentence. Similarly, a dialogue can only exist between two or more people or positions. To carry the linguistic metaphor further, like a verb in a sentence, art is a fragment within a larger whole. Moreover, art as action becomes part of a cosmopolitan present (Papastergiadis 2012): artists today create works, installations, conversations and situations that provide a space for the dialogue between culture and politics. Such works don't just 'represent', they act; they create spatial and temporal situations in which culture and politics intermingle in living, unfinished and relational ways.

In the field of art and politics, two principal changes have arisen in the last decade. First of all, the ever-present and increased circumstance of international political turbulence that has seen the movement of hundreds of thousands of refugees worldwide; the spirit of anti-globalisation that has created groups such as the Occupy Movement; and the courageous populations who have risen up against fundamentalist and oppressive regimes, such as during the Arab Spring. The increasing accessibility of social media has facilitated this renewed activism and turbulent environment. Secondly, contemporary art has shifted towards more relational, collaborative and collectivist projects, which are entangled with these changes in society. This essay does not seek to document all of these shifts, but rather highlight some of significant instances; for we can no longer see art and politics in simple binary terms – political/ non-political; withdraw/ participate; support/ protest; silence/ activism. Rather, there is a collaborative public sphere that is both political and artistic.

Art coupled with action has a long history and here we highlight just two trajectories. Australia has a unique, living Indigenous heritage that has relevance to this discussion. Let us consider three specific instances. First, in 1963, Yolngu artists from Yirrkala in Arnhem Land used their art form to petition the Federal Government about the excision of their land. The Yirrkala Bark Petitions were in English and Yolngu language and asserted that the Yolngu people owned the land over whichever mining leases for bauxite had been granted to British and French companies. These petitions are widely accepted as the first formal submission of native title.1

Second, it has been argued that the very act of painting in Indigenous 'country' entails a political action, for the painting expresses rights to homelands, a connection with ancient beliefs and represents an economic reality in terms of creating a viable source of income for a community. The son of one of the signatories to the petition, Galarrwuy Yunupingu, wrote: "We paint to show the rest of the world that we own this country, and that the land owns us. Our painting is a political act." (Yunupingu 1993)

Third, there are several significant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists whose work in multimedia, photography and painting expresses firm views on Indigenous issues. In 2010 Brisbane-based Indigenous artist Vernon Ah Kee created the video, Tall Man, based on the Palm Island riots of 2004 that emerged in the wake of the death in custody of Cameron Doomadgee. Lex Wotton, who has also been a subject of Ah Kee's painting, was incarcerated for initiating the riots (Reilly 2011). The four-channel video is a montage of footage taken by both participants and police during the riots. It is edited with no narrative voiceover. Instead, these amateur videos commingle across the four screens, as the riot evolves. Tension is high, emotions are palpable and the artist becomes an enabler for this story to be told.

These three examples – a historic bark petition, a significant comment by an Aboriginal elder and a video installation – are a selection (and not a continuum) of instances that demonstrate the diverse ways in which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists are cultural activists. This is true of artists from remote and regional communities whose work expresses, mostly through symbolism, an intricate balance of wisdom and land ownership, as well as artists working in the metropolitan centres, who often critique racism and address native title and dispossession of Aboriginal people. Action is embedded within these artworks. They carry within them a deep recognition of Indigenous beliefs and a troubled colonial history, along with a contemporary aesthetic expression. In a context where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health, education and living standards remain so far behind the Australian average, such cultural works are a call for change. In addition, they relate to a wider international zeitgeist, which has seen increasing visibility of indigenous rights and resistance to global corporate dominance. Artists such as Ah Kee have developed their work within a global context, in the sense that their aesthetic is in dialogue with international contemporary art. This second trajectory of art coupled with action can be traced back to the twentieth century avant-garde. It is critical to note that such strategies by Indigenous artists in Australia parallel and extend the innovations led by artists that range from Joseph Beuys to Thomas Hirschhorn.

In the Australian context during the 1970s, artists were involved in many protests. At the opening of the 1977 Biennale of Sydney protesters voiced their views both inside and outside the Art Gallery of New South Wales during Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser's speech, objecting to the cuts that had been made by his government to many sectors of society, including the arts. Between 1977 and 1979, there was widespread advocacy and lengthy negotiations between a working group of artists and the Biennale for both the inclusion of more Australian artists and the 50% representation of women artists in the exhibition (Gardner & Green 2013).2 These protests led to changes in the 1980s, such as the establishment of the Artworkers Union and the general advocacy for artists' rights and their representation on various boards. Some of those involved included Peter Kennedy and other artists associated with Inhibodress in Sydney, Vivienne Binns and members of the feminist art movement, Ian Milliss and Ian Burn and their involvement with the union movement, Michael Callaghan's poster collectives and the activities around the Tin Sheds Gallery at the University of Sydney. A similar set of concerns was evident in Melbourne, particularly in 1975 when 200 artists did a 'sit-in' at the National Gallery of Victoria in protest against the removal without consultation of a work by Domenico de Clario. They too advocated the need for the institution to be "re-structured physically, financially and administratively to make it responsive to the needs and interests of artists and the public in an expansively democratic way".3 During the 1970s the protests were focused on artists' rights and a call for artists' representation, involvement and participation in the decisions of the institutions of art.

Since the rise of the political unrest and anti-globalisation movements of the last decade, artists have focused on the public sphere with a renewed sense of urgency. They are heirs to these previous periods of activism, but, as the curator Manray Hsu has argued, there has been a shift in the ways in which artists and activists participate in what he calls "informal politics" (Hsu 2008). For Hsu, artists have the opportunity to "reclaim politics" in their ability and desire to consider human values in the public sphere. He suggests that attitudes in the street – the presence of migrants, refugees, public protests and the like – are where we can find politics. In his contribution at the recent Melbourne Art Fair forum, entitled "Going Public – Asian Perspectives on Contemporary Art", Hsu asked: "why do we find it so surprising when the public seeks to occupy public space?"4 Public space is part of a civic society. It is a space that experiences diverse uses, including mobility, media, assembly and exchange. Public space includes the cultural and societal chains of connections that occur in and through it. Working from the perspective of the public sphere, rather than the institutions of politics, the artist has the capacity to energise, multiply and reconfigure institutionalised perspectives on human values. In this context, art comes to be an exchange of ideas, an assemblage of imagery and, as such, is an active participant in the public sphere.

In 2014, in the 19th Biennale of Sydney You Imagine What You Desire, the Kurdish artist Ahmet Öğüt participated with a work entitled Stones to Throw (2011). He decorated stones with motifs derived from the comic book-style paintings that were created for military aircrafts between the two World Wars. He posted the stones to his hometown in Turkey, where children are regularly arrested for throwing stones at the military, and what remained in the exhibition were the FedEx bills and one solitary stone. Once they arrived in his hometown, the stones were discarded. Stones are thrown in the context of conflict. Aircrafts are painted in preparation for war, genocide and invasion. Images are circulated with the ease of a FedEx flight. But the people who received these images don't have such mobility and can't access global economic advantages. By creating this loop, the artist gives expression to conflict, economic globalisation, street art and activism. The work is at once an act, an action, a response and a set of relations. Inspired by the informal street politics of Kurdish children, the work activates public culture.

Ahmet Öğüt, Stones to Throw, 2011. Detail view from installation at Cockatoo Island, 19th Biennale of Sydney, 2014. Photograph by Ahmet Öğüt.

Öğüt was one of forty-six exhibiting artists who wrote to the Biennale Board expressing their concern about "a chain of connections that links to human suffering; in this case, that is caused by Australia's policy of mandatory detention". These artists were protesting against the principal sponsor Transfield's links with offshore detention centres.5 For these artists, the Biennale was their public sphere; a platform where they could agitate. They had a broad objection to both the policy and Transfield's involvement in it. Their letter could be seen as an extension of the methods of art as action outlined above. In a Biennale that defined itself in terms of 'desire', it is not surprising that many of the artists made art that gave rise to the consideration of human values. Their works variously make a contribution to how we understand notions of action and reaction, architecture and shared public spaces, surveillance and containment, conversation and interaction, collaboration and cosmopolitanism, social inclusion and exclusion, death and survival. This is not done with didacticism, but through methods that are situational and assembled.

Moreover, the letter did not distinguish between the role of the artist and the role of the Biennale, as they regarded the exhibition as a site for their work. They wrote: "We appeal to you to work alongside us to send a message to Transfield, and in turn the Australian Government and the public: that we will not accept the mandatory detention of asylum seekers, because it is ethically indefensible and in breach of human rights; and that, as a network of artists, arts workers and a leading cultural organisation, we do not want to be associated with these practices."6

The Biennale responded with the following: "The Biennale's ability to effectively contribute to the cessation of bi-partisan government policy is far from black and white. The only certainty is that without our Founding Partner, the Biennale will no longer exist. Consequently, we unanimously believe that our loyalty to the Belgiorno-Nettis family – and the hundreds of thousands of people who benefit from the Biennale – must override claims over which there is ambiguity."7

On receipt of this letter, several artist meetings were held in Sydney and Melbourne, and much dialogue occurred online through social media and a blog maintained by the journal Discipline, in order to analyse the complex relationship between the human suffering of refugees, art, corporate sponsorship and the symbolic role of a biennale in the global city.8 Nine artists chose to withdraw from the exhibition. In the weeks leading up to the opening of the exhibition, this two-fold demand concerning Transfield and the asylum seeker policy developed into a much larger protest led by activists who threatened to "stop the ferries" to one of the Biennale's main venues, Cockatoo Island. The Biennale chair and Director of Transfield Holdings, Luca Belgiorno-Nettis, resigned from the Biennale (citing the damage that was being caused to the Biennale) and the Biennale announced it was severing all ties with Transfield. After this announcement, seven of the nine artists who had withdrawn from the Biennale re-entered the exhibition, as they felt that they could then continue with their artwork.

It is worth reiterating the responses to these actions, since they were mostly extremely negative. Leading politicians immediately went on talkback radio and admonished the artists. Malcolm Turnbull, Minister for Communications in the Australian Government accused the artists of "vicious ingratitude"; the Attorney-General and Minister of the Arts, George Brandis, wrote a "strongly worded letter" to the Australia Council for the Arts indicating that he would seek to punish any arts organisations which reject corporate funding on the basis of ethics. He requested that the Council redraft the policy concerning the links between government funding and corporate sponsorship. The Council is still apparently working on the 'wording' (Marr 2014, p. 27). Brandis further stated that the Biennale board had been 'bullied' by the artists. These comments succeeded in skewing the debate. Rather than focusing on asylum seeker policies, the media focused on the vexed question of culture and sponsorship. Museum directors, cultural commentators, and visiting Biennale curators and journalists were united in their fear that: a) the Biennale would not survive; and b) sponsors would withdraw support from risky contemporary art centres and exhibitions – such is the reliance on private funding for the arts. The ensuing discussion was almost entirely about the economics of arts funding. When the issue of asylum policy arose, a common refrain was: why accept government grants for artists if you do not agree with the government (thirty-three of the forty-six signatories were not even Australian citizens), somehow ignoring the fact that: a) the government earns income from the citizen's taxes; and b) arts funding is at arm's length.9 In short, a large part of the discussion bordered on the hysterical, such was the shock at Transfield's departure from the Biennale.

In effect, the artists wanted a shift: from Transfield's Biennale to the artists' Biennale. In this, there are echoes of the protests of the 1970s. In some cases a plea was made for a requirement that the composition of the Board also reflect the contribution of the art world (by the inclusion of an artist, art critic, curator and / or an arts academic) and not, as is currently the case, exclusively patrons of the arts (Papastergiadis 2014). In the 1970s the Board included curators, arts administrators and the patron. The current Board of the Biennale is unlike most other arts institution boards. In addition it should be noted that on 9 September 2014, Transfield Holdings sold its shares in Transfield Services, divesting the founding patron's financial benefit from off-shore mandatory detention (Taylor 2014). Shortly, after this 'sell off' a new scandal concerning the abuse of refugees was made public.

Along with this request for institutional change, the artists demonstrated that public culture located in public spaces belongs to all of us and is intimately connected with a set of civic values. In one sense, this was not revolutionary but simply required the Board to govern with a civic charter (as many boards in the not-for-profit sector do). There was the further belief that mandatory detention contradicts these same basic civic values, which include the right to asylum and with that, dignity and respect. In the context of the changes in art over the last decade or more, the artists in the Biennale are in collaboration with the social fabric and the public sphere, not separate from it. Their work, ideas, comments, writings and research make an active contribution to that sphere, which has been referred to as the "cosmopolitan imaginary" (Papastergiadis 2012). The Biennale forms part of this sphere, where there are intersections of politics, diverse views and multiple cultural expressions.

The artists took different positions in the debate: some chose not to sign, others signed, some permanently withdrew, others returned, and some chose to use the privilege of participating in the Biennale to alter their works and create pieces sensitive to the detainment of asylum seekers. It is worth pausing to consider the act of withdrawal in this context. The word 'withdraw' was deliberate. 'Boycott' was not referred to in the letters, despite being frequently reported in the press. We would argue there is a difference of degree between the two words. To withdraw their works was an act of departure but it was coupled with the insistence that this withdrawal be signposted in both the exhibition and website in the form of a trace. To withdraw is to create a pause that interrupts the normal flow of associations. In this spirit the signatories requested negotiation and collaboration. They saw the 'withdrawal' as an action that, like a verb, was in relation to opposing points of view. Boycott on the other hand appears to be a much more non-negotiable position, and one that seeks to close dialogue down.

The withdrawal by nine artists created this negative space, both within the imaginary and in the exhibition itself. In creating this space, a new set of processes emerged between the artists themselves, the community and the Biennale. The Biennale protests showed that the realms of politics and creativity are not separate but entangled processes that are always in the province of a 'verb'. As such, the desire was not to shut the Biennale down, but to embrace the public nature of a public event.

Celebrated Australian author Thomas Keneally recently lamented that "we no longer live in a society, we live in an economy" (Keneally 2014). On this occasion, the Biennale artists were widely portrayed as actors in an arts-funding soap opera, rather than as the active participants and enablers that they are in a complex public sphere. However, artists make worlds, sometimes in collision with one another, but their art is a world-making activity. Artists contribute to civic society and create and enrich connections that are not always found in daily life. Their "line in the sand" was, on this occasion, too significant to remain silent. They challenged the Biennale, Transfield and, to an extent, the Government to reconsider the human suffering that is mandatory detention. It seems that this action has had no impact on the governance models of the Biennale of Sydney. Despite all the criticism that the membership of the Board of Directors was not representative and out of touch with the community, all the new appointments continue to reflect a corporate agenda. This is a dangerous global trend. The action taken during the Biennale of Sydney is by no means exclusive to Australia, with colleagues in biennial exhibitions around the world – Istanbul in 2013 and Gwangju, São Paulo, St Petersburg, and Moscow in 2014 –expressing their respective concerns with equal conviction.

Bibliography

Erdemci F. and Cruickshank A. 2014, "Art does not come from a clean white room: Biennales, corporate sponsorship and dirty money", Broadsheet: Contemporary Visual Art + Culture, Adelaide, vol. 43, no. 2, June.

Gardner A. and Green C. 2013, "The Third Biennale of Sydney: 'White Elephant or Red Herring?'" in Turner, C., Antoinette M. and Stanhope Z. (eds.), Humanities Research, The Australian National University, Canberra, vol. XIX, no. 2, viewed 5 September 2014, http://press.anu.edu.au

Hsu, M. 2008, "Manray Hsu taking a political position", interview with the author, Artlink, vol. 28, no. 4.

Keneally, T. 2014, Q & A, ABC TV, 26 May.

Marr, D. 2014, "Freedom Fighter", The Monthly, September, p. 27.

MacGregor, L.A. 2014, "Surely we want more debate not less", Daily Review, 25 February, viewed 16 July 2014, http://dailyreview.crikey.com.au/liz-ann-macgregor-surely-we-want-more-debate-not-less/

Mendelssohn, J. 2014, "Artists' victory over Transfield misses the bigger picture", The Conversation, 8 March, https://theconversation.com

Ögüt A. and Begg Z. 2014, "A question of ethics: The Biennale of Sydney and artists' protest", Broadsheet: Contemporary Visual Art + Culture, Adelaide, vol. 43, no. 2, June.

Papastergiadis, N. 2012, Cosmopolitanism and Culture, Polity Press, Cambridge.

Papastergiadis, N. 2014, "Transfield and the Board of Sydney Biennale Just Don't Get It!" and "Zoom Out and See the Bigger Picture", Discipline, issue on the Biennale of Sydney 2014, Melbourne

Reilly, M. 2011, "Vernon Ah Kee: Tall Man", review, ArtAsiaPacific, issue 73, May/ June, p. 136.

Taylor, A. 2014, "Biennale artist takes some credit for Transfield share sale", The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 September, viewed 16 September 2014, http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/art-and-design/biennale-artist-takes-some-credit-for-transfield-share-sale-20140911-10flol.html

Yunupingu, G. 1993, "The Black/White Conflict",Aratjara: Art of the First Australians, DuMont Buchverlag, Cologne, pp. 64–65.