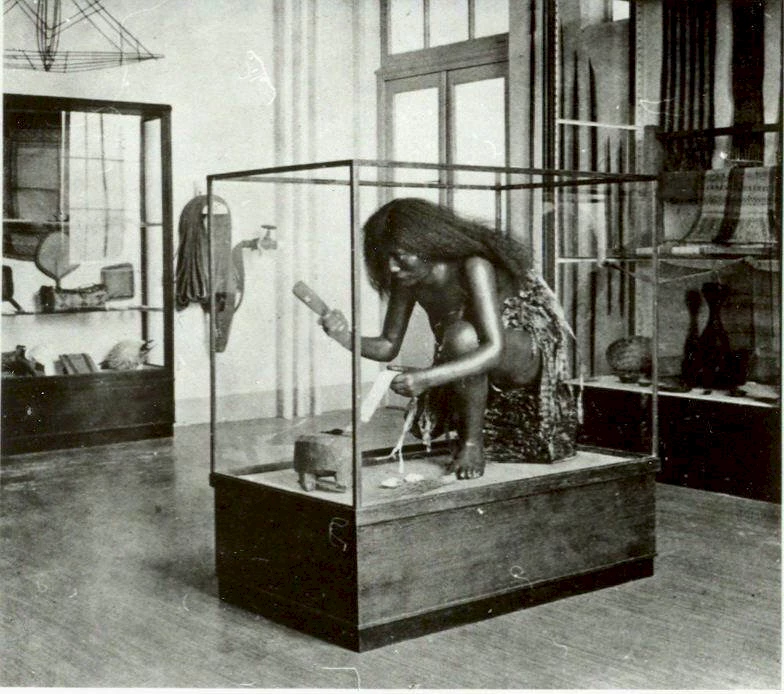

Historical exhibition display in the Museum für Völkerkunde (today Weltkulturen Museum), Oceania section. Weltkulturen Image Archive. Photo: Hermann Niggemeyer, date unknown.

MATERIALITY1 AND THE UNKNOWN, DATING, ANONYMITY, THE OCCULT

Collections have an anthropomorphic, fetishist feel to them. They are both about our failings and about our successes. They signify relations between things and ideas, between the inheritance of meaning and its erasure over time. In its singularity and ubiquity, the ethnographic museum can be seen as a household of foreign matter, of stuff that is diasporic, immigrant, domestic, bourgeois, effusive, feral, reclusive, rehabilitating, convivial, consumerist, curious, concerned, failed, and obsessive.

In the past, ethnographic museums not only collected the everyday, they sought out representations of life's unknowns. The unknown, unchartered, unexplainable, even the uncanny were part of the anthropologist's fascination with the Other and his bugchasing desire to put the status quo at risk.

In the late 1920s, Michel Leiris wrote: "I would rather be possessed than talk about the possessed", and so in 1931, he left Paris behind, along with its conventions and correctives of everyday life, and embarked on a collecting expedition that would take him from Dakar to Djibouti, seeking a transducer into the unknown.

At certain moments, this unknown is believed to be contained in the material object. But it is an unknown that needs to be possessed too, crazed yet controlled, tamed and classified. This process tended to take place back to base, through administration, writing and photography. In Europe, ethnographic objects were given a date – as if they had been orphaned and needed to be parented anew – founded on when they were acquired, purchased, or even looted, but not when they were originally produced. The question was rarely asked at the moment of appropriation. Instead, it was the time of coupling, the relational moment with the colonial, which became a marker.

Exhibition view: El Hadji Sy: Painting, Performance, Politics, 2015. El Hadji Sy: Portrait du Président, 2012. Acrylic and tar on butcher’s paper, 190 x 200 cm. Collection of the artist. El Hadji Sy: Le Puits, 2014. Acrylic and tar on jute sacking, 245 x 280 cm. Collection of the artist. With stools, collected by Meinhard Schuster and Eike Haberland 1961, Papua New Guinea, wood. Collection Weltkulturen Museum. Photo: Wolfgang Günzel.

Exhibition view: Foreign Exchange (or the stories you wouldn’t tell a stranger), 2014. Photographs of the collection (1960–2013) plus new works by Marie Angeletti, Otobong Nkanga, Benedikte Bjerre. Photo: Wolfgang Günzel.

If these objects were once deemed auratic – in other words, they held you under their spell – once back in Europe they quickly lose their original fascination, acquire patina, even anachronism, and appear past their sell-by date. Over time, the custodian's collection in its outrageous heterogeneity transforms into a pedestrian series of household articles, which purport nevertheless to be tools of enquiry. There are hierarchies of objects too, just as there are hierarchies of people, and of continents. These pyramids of classification, those nomenclatures that proffer capital onto things, those masterpieces that reoccur (Benin, Baule, New Britain...), and the photographs that are taken in studios all help to boost what is missing and produce the necessary commodification.

If, today, mass collecting for ethnographic museums has necessarily come to a standstill, which institutions today are still able to place a purchase on life's unknowns? What might a contemporary ethnographic collection look like? Would it be the entire contents of a department store full of the world's functional items and luxury goods with their mixed cultural heritage, skewed authenticity, and multiple producers? Or has the acquisition of life's unknowns shifted from the earlier speculative and occult interests of ethnographers and their museums to the rising market in globalising collections of contemporary art? What do we do with what exists and is in storage?

Research Assemblage, Weltkulturen Labor, 2011. Photo: Wolfgang Günzel.

STAGNANT COLLECTIONS VERSUS DYNAMIC SCHOOLS OR MUSEUMS

Writing in the 1920s when the blood pressure of collecting was at a high, Carl Einstein, the German theoretician of African art, contemporaneous with Walter Benjamin and Aby Warburg, argued against the idea that objects from the past possessed an inherent kind of material and sentimental immortality. He claimed this view contradicted the historical process and represented what he called a "terrible legacy", which "falsifies the past (...) and sprinkles fiction and dead perceptions into the present". Einstein sought to nurture an intellectual lifeline between the museum and the research institute. In his view, the greatest strength of a collection lay in its mobility. In other words: in the intentional act of switching the position of exhibits back and forth from analysis and interpretation to public visibility.2

Einstein claimed that the itinerancy of objects within collections would make people look again, better understand what they saw, and take apart what they believed or assumed. Collections would reflect extremes of intellectual exploration and exhibitions would speak of human experience and knowledge. Otherwise, he claimed, museums would become nothing more than "preserve jars", and "anesthetize and rigidify into a myth of guaranteed continuity, into the drunken slumber of the mechanical".

What Einstein was suggesting was that the museum's engine room lies in the recognition of its research collection: "In dieser vergleichenden Sammlung vor allem müssten Vorlesungen und Führungen veranstaltet werden; wie die gesamte Schaustellung durch Lehrer verlebendigt werden muss. Hier ist der Punkt, wo die lebendige Bindung zwischen Museum und Forschungsinstitut einzusetzen hat, soll das Museum nicht durch das Fachpopuläre nur Schau und nicht Lehre gewahren." Today, nearly one hundred years after Einstein's quasi-manifesto for a dynamic museum,3 it does not take much to recognise to what degree these public institutions have become entrenched within the corporate culture of consumption on an increasingly global scale.

Recently the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris was described to me as being similar in remit to a television broadcaster such as Arte, or a publishing house like Taschen. The role of its exhibitions is to provide well-produced, colourful, attractive, and topical visions of the world with a touch of popular exoticism. After all why would one battle against industrial forms of populist trans-cultural entertainment? Indeed, the same museum in Paris runs one of the most interesting research branches in Europe, headed by French scholar Frédéric Keck who studied under Paul Rabinow. Keck is a specialist of contemporary animal-engendered epidemics who spent two years engaging with the 100-year-old Claude Lévi-Strauss before he died. Yet at the Quai Branly, the cohabitation of partner forms of curating knowledge – one for the purpose of public exhibiting, and the other ideational and charged with advanced developments, which remain largely backstage – is taken to an extreme. Critical reception is divided – some complain about Jean Nouvel's dark cavernous coloured concrete scenography, whilst applauding the museum for its excellent médiathèque, library, photographic archives, digitised collections, international symposia, and close collaborations with global academia. Rather than symbiotic, these two strands appear lodged in a hiatus that contradicts the stored capital of this museum: its extensive ethnographic collections.

What kind of meaning does one want to produce today on the basis of such collections, collections that appear to have reached the dead-end of research? What role do they play in relation to universities? What modus operandi can be introduced today so that these heteroclite, anachronistic objects from the past are recharged with contemporary meanings? If museums have to fight against routine, habit, and conservatism, what kind of working method can we develop to reactivate the reservoirs they hold once more?

To think of ways of curating, caring for and reconfiguring an ethnographic collection in 2014 is urgent. Instead of obfuscating access to these important objects due to an ideology of conservation, one should remediate them in a meaningful way. This is important because it helps to establish new ways of defining collections, breaking down the earlier hierarchies between high and low, between masterpieces and those artefacts relegated to everyday life. As anthropologist Paul Rabinow suggests, "The exercise is how to present historical elements in a contemporary assemblage such that new visibilities and sayable things become actual inducing motion and affect".4

Exhibition view: Foreign Exchange (or the stories you wouldn’t tell a stranger), 2014. Installation by Luke Willis Thompson: Skull Mask (Lorr), collected by Carl Gerlach 1879, New Britain, human bones, plant fibres and paint. Collection Weltkulturen Museum. Photo: Wolfgang Günzel.

REMEDIATION

In the first, perhaps more contemporary sense of the term, 'to remediate' means to bring about a shift in medium, to experiment with alternative ways of describing, interpreting and displaying the objects in the collection. To remediate also implies to remedy a deficient situation, for example, the ambivalent resonance of the colonial past (Rabinow 2008). The earlier assumption of epistemological authority does not extend comfortably within the post-colonial situation. One can no longer be content to use earlier examples of material culture for the purpose of depicting cultures, ethnic groups, thereby reasserting the logos of ethnos or an existing range of outdated anthropological themes. Of course, we respect and critically integrate earlier narratives and analyses written by anthropologists and area experts, just as we take on the existing testimonials that originate from the producers and users of these artefacts. But we can also expand the context of this knowledge by taking the artefacts once again as the starting point and stimulus for contemporary innovation, aesthetic practice, linguist translation, future product design, and triggers for emergent museums. But how does one demystify them, activate a loss of aura? How does a collection "regain consciousness" or create presence anew?

As one knows, bullë matter, is first of all wood. And since this becoming-immaterial of matter seems to take no time and to operate its transmutation in the magic of an instant, in a single glance, through the omnipotence of a thought, we might also be tempted to describe it as the projection of an animism or a spiritism. The wood comes alive and is peopled with spirits: credulity, occultism, obscurantism, lack of maturity before Enlightenment, childish or primitive humanity. But what would Enlightenment be without the market? And who will ever make progress without exchange-value.

(Derrida 1993/1994)

To remediate the ethnographic collection is to engage with that mix of discomfort, doubt, and melancholia, the caput mortuum phase of alchemical regeneration, transforming these objects into a contemporary environment and thereby building additional interpretations onto their existing set of references. This initial experimental phase yields new ideas for works that operate as prototypes, as stimuli for subsequent elaboration. They are unfinished collections just like the ethnographica is unfinished in its semanticity. In this sense, the new prototypes interpellate the various models of concept and form embodied within the artefacts from the museum's collection.

Exhibition view: Foreign Exchange (or the stories you wouldn’t tell a stranger), 2014. Installation by Peggy Buth. Photo: Wolfgang Günzel

THE RESEARCH COLLECTION

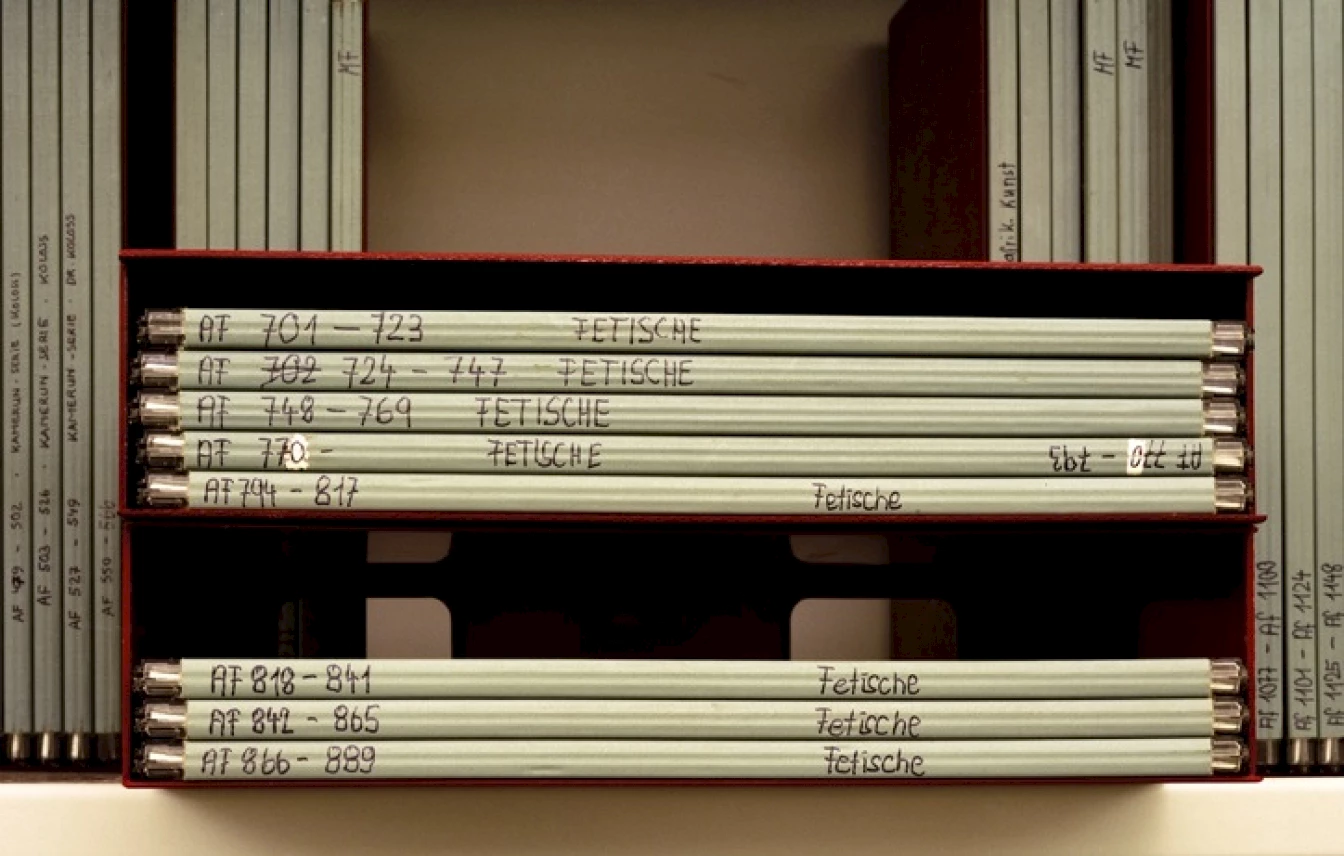

No research collection can be a viable commodity for long. The spectral chain is broken once its decoding procedure has been superseded and relegated to a past enquiry. Nevertheless, the objects in these collections – in particular those associated with ritual and therefore doubly fetishistic – retain something, and that something is what people search for in the museum. They search for transportation, for the steamship, the airplane, or the hologrammic virtual log-on into the mystical enigma. Their use-value may be interesting, but as Karl Marx and then Jacques Derrida pointed out, that is not how the numinous character of the material object is constituted. "The commodity is even very complicated; it is blurred, tangled, paralysed, aporetic, perhaps undecidable (ein sehr vertrachtes Ding)" (Derrida 1993/1994).

There is a kind of failure that subtends the ability of this mass of ethnographic objects to be commoditised. These objects are failures because they can never be us, be an unquestioned part of our referentiality. As such their referentiality is not expended. They are contested and will continue to be contested. And the argument for their future restitution is undeniable. Distance is what makes them what we want from them. We want them to be a contrast medium to what we know.

The Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt which I have been directing since 2010 has a store of 70,000 such objects. In this case, the resistance to commodification becomes all the more apparent and persistent. Why would one object dominate? If one does dominate, it is because of a market in tribal art. The existing conservatism of the tribal art market with its implicit top twenty – in which a piece from Nok or Benin was at the top of the scale and a set of woven rattan fish traps from the Sepik at the bottom – no longer retains its ideological status. The associated apparatus of display, including genres of lighting and photographic imaging, are critically reviewed when thinking of post-ethnographic presentations.5 If one breaks that market lineage, the provenance that fetishises who owned what when, who stroked which sculpture, or introduced it into their frame of reference, brought it into a relationship of affinity and transported through it – like a Ouija board séance on the table that Marx and Derrida refer to as the figurante in a play – then something begins to happen. The commoditised tribal art object suddenly shows up its naked, orphan-like status, its anachronism, out of timeliness, simply out of joint. These are fugitive works of art in fugitive collections. For an object is a migrant too with its partial knowledge, partial identities, and incompleteness (Sassen 2009).

One could argue that the claims for restitution, for returning the millions of objects to where they once came from is currently the most active form of commodification that is taking place. The relic diplomacy surrounding these artefacts insist that the material objects should be returned to the source communities even if these are so radically displaced that no one can be sure that a receiver will be there – other than the market.

Rut Blees Luxemburg, Afrika II (Fetishes), 2013.

WHAT TO DO? THE SEED OF A MUSEUM UNIVERSITY

As Joseph Beuys said in 1975, "I want to turn museums into universities that have a department for objects... The museum could offer the first model for a ongoing (or permanent) conference on cultural issues" (Beuys and Haks 1993).6

I have spent four years exploring the presence of historical objects in ethnographic museums. It has led me to claim their potentiality for a contemporary form of artefact-led or collection-centred cross-cultural interdisciplinarity, a situation of enquiry that might even lead towards something which I dare to call a museum-university, a hybrid formulation of an art college, a university, and a museum, geared to accommodate new professional formations on the basis of an investigative reactivation of contentious and disputed historical collections.

If one breaks down the elements that require attention today and might constitute the foundation of a new type of working location, the following elements spring to mind:

1. The – quite literally – millions of objects collected from around the world that sit in the stores of the ethnographic museums of Europe. Germany – I would estimate – has about 4 to 5 million. If this is multiplied by what is in storage in Britain, France, Belgium, Portugal, Austria, Italy, Spain, there is a serious quantity of phenomenally important "art works" of ingenuity and meaning. (We will not enter the polemic of ethnographic object versus the art work or craft here).

2. A further area of attention is the flourishing of new sectors that combine disciplines and seem to have no institutional roof other than annexing universities or art school departments: cultural studies, curatorial studies, critical colonial studies, post-colonial studies, critical race and anti-colonial studies, and various museum studies in addition to the redefinitions of existing partner discourses in art history, art, anthropology, area studies (e.g. South-East Asian or African Studies). These new sectors are emerging on a global scale. It is no longer just occurring in Birmingham as was the case when Stuart Hall and Dick Hebdige created Cultural Studies and brought attention to subcultures and diasporic histories in Britain. Today, you can study cultural and curatorial studies or museology, for example, in numerous cities on the African continent, in South East Asia, India, Japan, Latin America, and probably China too.

3. Finally, there is the issue of collecting. The visibility and contemporaneity of collections lies today with private initiatives and personalised museums. In contrast, cities in which state museums once flourished after their respective countries' independence (e.g. Jakarta, Delhi, Lagos, Dakar, to name just a few) are hindered when it comes to activating a renaissance of their cultural institutions, which are regarded today as ideologically outdated, unable to pull in visitors, and generally dilapidated. The civil service of museum professionals compounds the difficulties that exist in engaging younger generations of museologists and curators within these national or municipal venues.

Otobong Nkanga talking about her work during the Think Tank '…persecuted, mourned, pitied, photographed, collected…', 16–17 May 2013, in preparation for the exhibition Foreign Exchange (or the stories you wouldn’t tell a stranger).

At the Weltkulturen Museum, we have developed an experimental methodology, which I believe is not only possible within the post-ethnographic museum but can be applied to other museums with varied historical collections. It depends on how one views the possibility of knowledge production within a museum and defines hierarchies within collections. To test this way of working with collections by engaging with a former colonial museum of anthropology aggravates questions of access, ownership, restitution, conservation, and oblivion that may also apply to other museums but to a lesser degree.

The potential of a research collection is that it is contingent on experiment and dialogue yet quickly loses its currency. As such it remains oddly outside of market forces yet characterises and punctuates the exploration of the moment. This process is connected to production and therefore to the emergence of a new collection, one that quite literally grows out of care and attention to historical antecedents.

The unfinished works produced in the Weltkulturen Museum's Labor evoke what one might define as the prelusive moment. Prelusive qualifies the object or experience that triggers a principal event, action, or performance. Often associated with composition and structure, the prelusive phase is the instance of anticipatory and transformative thinking that can lead to the early shaping of ideas and the subsequent creation of a new body of work.

The Weltkulturen Museum builds up an unfinished collection of emergent works of art or literature created on site, in its laboratory. These works reflect an intimate fieldwork situation, and an acute interaction by the guest artist or scholar with the specific context of the museum and its artefacts, photographs, people, situations, and exhibitions. It is about decoding the tacit knowledge of objects by using small in-roads rather than mainlines within existing anthropological discourse. The Labor in the museum is "pre-operational". It is a green room for production. It provides the researcher with a framework for living, sleeping, working, thinking, reading, producing – a kind of domestic inquiry that takes on night-work and adjusts to the domestic scale of a villa.

At the end of each residency, the artist or scholar gifts an example of this new emergent work to the Museum. By entrusting the museum with these new prototypes based directly on objects from the collections, guests pass on another form of relational knowledge to students, colleagues, and members of the public. This process can provide the framework for an innovatory form of education within the museum that communicates the extremes of intellectual exploration, a conceptual and reflexive exercise in things as yet unknown.

In this way, we can view the different artefacts from past collections as vehicles of cultural translation today, operating in the tension and traction between pedagogy and performativity: pedagogy with its "continuist, accumulative temporality" (Bhabha 1994, Chapter 8) and performativity that engages with the recursive language of creative adjustment. This may help us to redefine the condition of mobility that Carl Einstein referred to in relation to the museum's research collection.

This is the seed of a new museum-university, constantly working with external impulses and redrafting the concept of generalism and the democratic intellect towards a non-standardised education, independent and self-organising, a subjective, permeable, fragile institution.

Bibliography:

Bhabha, H.K. 1994, The Location of Culture, Routledge, New York.

Beuys J. and Haks F. 1993, Das Museum – Ein Gespräch über seine Aufgaben, Möglichkeiten, Dimensionen, FIU Verlag, Wangen.

Derrida, J. 1994, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International, trans. Peggy Kamuf, Routledge, London and New York, original work published 1993.

Einstein, C. 1926, (Berliner Völkerkunde Museum), quoted in Uwe Fleckner, Carl Einstein und sein Jahrhundert. Fragmente einer intellektuellen Biographie, Akademie Verlag, Berlin, 2006.

Einstein, C. 2004, Various texts translated by Charles Haxthausen, October 107, MIT Press, Cambridge, Winter.

Leiris, M. 1934, L'Afrique Fantôme, Gallimard, Paris.

Rabinow, P. 2008, Marking Time: On the Anthropology of the Contemporary, Princeton University Press, New Jersey.

Sassen, S. 2009, "Incompleteness and the Possibility of Making: Towards Denationalized Citizenship?", Cultural Dynamics, vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 1–28.