"Decolonising Museums" through the lens of the collections and archives of the members of L'Internationale

Clémentine Deliss' article "Collecting Life's Unknowns" was a starting point for this EPUB publication by L'Internationale Online, reflecting upon the collections and archives held by the members of the confederation. Referring to Deliss' remark about the research potential of collections, MACBA addresses The Green Detour, a nine-volume comic by Francesc Ruiz in which he uses popular culture to create alternative narratives around emblematic moments in Egypt's cultural history. M HKA writes about the Vrielynck Collection of antique cameras, optical toys, film posters and other cinematographic paraphernalia: through a series of artists' interventions, the museum examined the potentialities of this collection for researchers and artists. Van Abbemuseum explores the parallels between anthropology and contemporary art in an installation by Michael Rakowitz, The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist. Moderna galerija presents the work Lenin – Coca-Cola by Alexander Kosolapov and related artefacts to discuss art as an invention by Western culture and predict the shift from work of art back to artefact.

–Christiane Berndes, Curator and Head of Collections Van Abbemuseum

Michael Rakowitz, The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist, 2009–2010. Plywood, packaging and newspapers from the Middle East, graphite on vellum, audio, dimensions variable. Collection Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven.

FROM THE COLLECTION OF THE VAN ABBEMUSEUM, EINDHOVEN

Contemporary art and ethnography

Could the contemporary artist be the new anthropologist? This question came to mind while reading Clémentine Deliss' text "Collecting Life's Unknowns", and finding connections with works in the Van Abbemuseum collection. This context leads us to highlight The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist (2009–2010), an installation by American-Iraqi artist Michael Rakowitz that was acquired and installed at the Van Abbemuseum a few years ago.

The work is centred on the looting of artefacts from the National Museum of Iraq, Baghdad, in the aftermath of the US invasion in April 2003. It was only after severe criticism from the international community that the government came to help. Approximately 15,000 objects – the oldest dating back to around 4000 BC – have been destroyed, or stolen and sold on the black market. At the moment about 7,000 are still missing. The installation consists of papier-mâché reconstructions of the missing artefacts made from the packaging of Middle Eastern foodstuff and local Arabic newspapers. Rakowitz lives in the United States but has roots in Iraq. Using the University of Chicago's Oriental Institute database and Interpol's website, he created the copies together with a team of assistants. These are displayed on a long table that borrows its form from Aj-ibur-shapu, the ancient Babylonian Processional Way through the famous Ishtar Gate. The title of the installation, The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist, is derived from this name.

Thus, the second element of Rakowitz's installation links the looting of 2003 to a story from the beginning of the twentieth century which is told in the framed drawings hanging on the walls. Carl Einstein, the German theoretician of African art mentioned by Deliss as the advocate of the Dynamic Museum, wrote about his ideal museum where "collections would reflect extremes of intellectual exploration and exhibitions would speak of human experience and knowledge". During excavations in 1902, the German archaeologist Robert Koldewey discovered the Ishtar Gate, one of the eight gates to the inner city of Babylon constructed on the north side by order of King Nebuchadnezzar II around 575 BC. Koldewey transported this Gate to Berlin, where it is still on view as one of the highlights of the Pergamon Museum. The gate that was photographed and posted on the Internet the most by US servicemen stationed in Iraq is a 1950s reconstruction on a ¾ scale compared to the size of the original.

A third element in the work is the story of Donny George Youkhanna, who was director of the museum during the time of the invasion and the looting in 2003. Dr. Youkhanna was also a member of the band called 99%, that covered songs by the UK heavy metal and hard rock band Deep Purple. One of their songs, "Smoke On The Water" from 1972, is played continuously in the installation. It is interesting to position the popularity of Western pop music against the near-total financial and trade embargo established by the United Nations Security Council on the Iraqi Republic, starting four days after Iraq's invasion of Kuwait and until May 2003. Security measures were taken by the United States to defend government buildings against looting in the aftermath of the invasion, but they left cultural institutions like the National Museum to their fate.

Rakowitz's work addresses the migration of goods in colonial and postcolonial times, creating and destroying identity through power, law and value systems. By recreating the missing objects from worthless packaging and newspapers and with the help of different modern information systems, Rakowitz transfers them into the discourse of contemporary art, where they testify about the complex exchange between different cultures within a globalised world, our world.

–Christiane Berndes, Curator and Head of Collections Van Abbemuseum

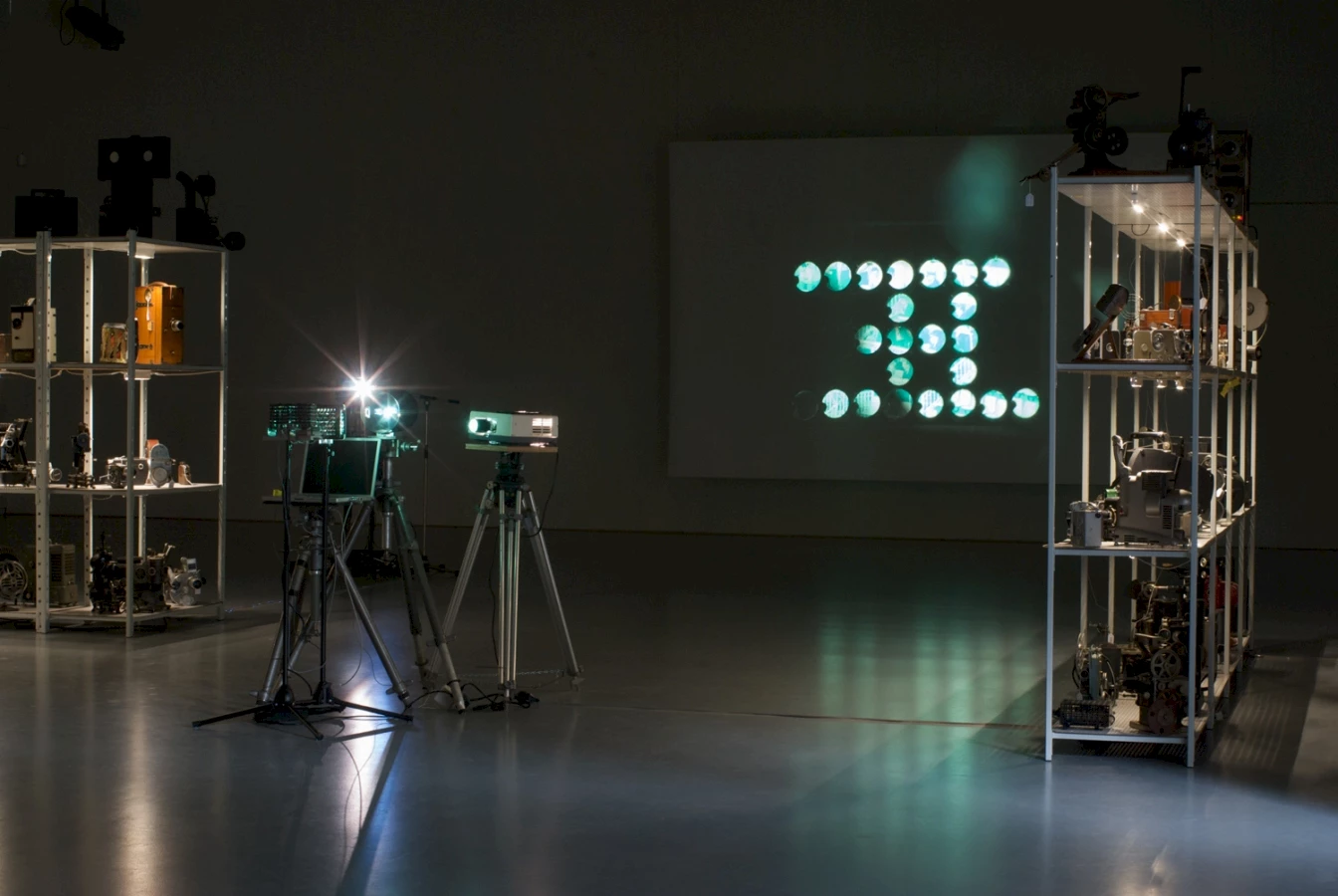

2011 EXHIBITION, Julien Maire, Mixed Memory, FOMU. Collection M HKA, Antwerp.

2011 EXHIBITION, Julien Maire, Mixed Memory, FOMU. Collection M HKA, Antwerp.

2011 EXHIBITION, Julien Maire, Mixed Memory, FOMU. Collection M HKA, Antwerp.

2011 EXHIBITION, Julien Maire, Mixed Memory, FOMU. Collection M HKA, Antwerp.

FROM THE COLLECTION OF M HKA, ANTWERPEN

Contemporary art and remediating a collection of media-archaeological objects

In her text "Collecting Life's Unknows", Clémentine Deliss explains the term 'to remediate' in relation to recharging ethnographic collections with contemporary meanings, to experiment with alternative ways of describing, interpreting and displaying these heteroclite, anachronistic objects. Alongside a collection of contemporary art, M HKA also has the Vrielynck Collection, a collection consisting of media equipment. What is a museum of contemporary art supposed to do with a collection of antique cameras, optical toys, film posters and a large amount of other cinematographic paraphernalia? M HKA regards this collection as an area of study for researchers and artists; a collection which can play a crucial role in giving us a better insight into our visual culture. Between 2011 and 2013, the Vrielynck Collection was the source of research for a series of exhibitions curated by Edwin Carels with artists such as Julien Maire, Zoe Beloff, and David Blair.

In 2003 the former Centre for Visual Culture, now Cinema Zuid and part of M HKA acquired the Robert Vrielynck Collection with the aid of the Flemish Community. Robert Vrielynck was a solicitor from Bruges who also cultivated a collector's reflex for any object relating to the history and technology of moving pictures. He acquired various models of camera obscura, magic lanterns and 16mm cameras, as well as early video equipment. This rich and somewhat eclectic collection also includes a large number of film posters. A smaller section of the collection consists of so-called pre-cinema devices, a term which is increasingly being replaced by that of media archaeology.

By granting the M HKA this collection, the Flemish Community gave it a proper home for the first time. Moving it from an improvised storage space in a garage to the climate controlled rooms of a museum also changed its significance as a whole. Not only did a private collection become public property, but a fanciful, idiosyncratic amalgam of cinematographic equipment now entered the realm of contemporary art. According to Carels, "The camera, which freed painting from its obligatory realism and at the same time immensely increased the impact of the artistic image because it enabled such rapid reproduction, now has become a museum object itself – or at least it shares the same waiting room, the museum reserves".

It would be an admission of weakness to treat the media-archaeological objects in the Vrielynck Collection as a separate category, as an outsider within the whole discourse of the museum. The relationship between art and visual culture is as obvious as it is problematic, particularly now that not only filmmakers and video artists make prominent use of the camera as a medium, but all manner of other artists too. In 1935, in his classic essay "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction", Walter Benjamin published a critical ode to both the photographic and film cameras – and especially their impact on our perception on historical, social and sensory levels.

The antique equipment and artefacts deserve better than to simply be put into storage as examples of instruments from various episodes in visual culture that now definitively belong to the past. However, the museum prefers to regard the collection not simply as something to be stored but as a reserve, an area of study for both researchers and artists. Indeed, eliciting new interpretations is precisely the underlying strategy that regularly recurs in M HKA programmes: artists are invited to use the collection to produce an 'intervention'. Consequently, and in association with the curator Edwin Carels, the museum set up a series of three exhibitions in which contemporary artists were invited to shed their own light on the Vrielynck Collection.

VRIELYNCK COLLECTION #1

Julien Maire – Mixed Memory

09.02–05.06.2011

The first in the series was an exhibition by Julien Maire, Mixed Memory, in which Maire incorporated elements of the Vrielynck Collection into three of his installations. Maire works at the crossroads between installation art, performance and media art. For many years he has focused on reviving early projection techniques with the aid of modern technology. The extinction of analogue images – in favour of digital images – endows the cinema apparatus such as it has found in the Vrielynck Collection a new status: these objects of a history-in-progress have suddenly become archaeological. The complex mechanisms that configure analogue images have been replaced with digital equipment. In his work Julien Maire clearly enters into dialogue with history and media, paradoxically enough by designing a new technological apparatus. Through his manipulations he raises questions regarding the characteristics of the image, the viewer's position and visual strategies in the digital age. By combining past and current technologies, in the exhibition he did not show 'relics', but rather reactivated them. For his presentation at M HKA he brought together instruments in which he incorporated objects from the Vrielynck Collection. In one of his installations titled Memory Stations, he manipulates anonymous films and stills in a special way. He reconstructed a collective memory that is part human, part technological.

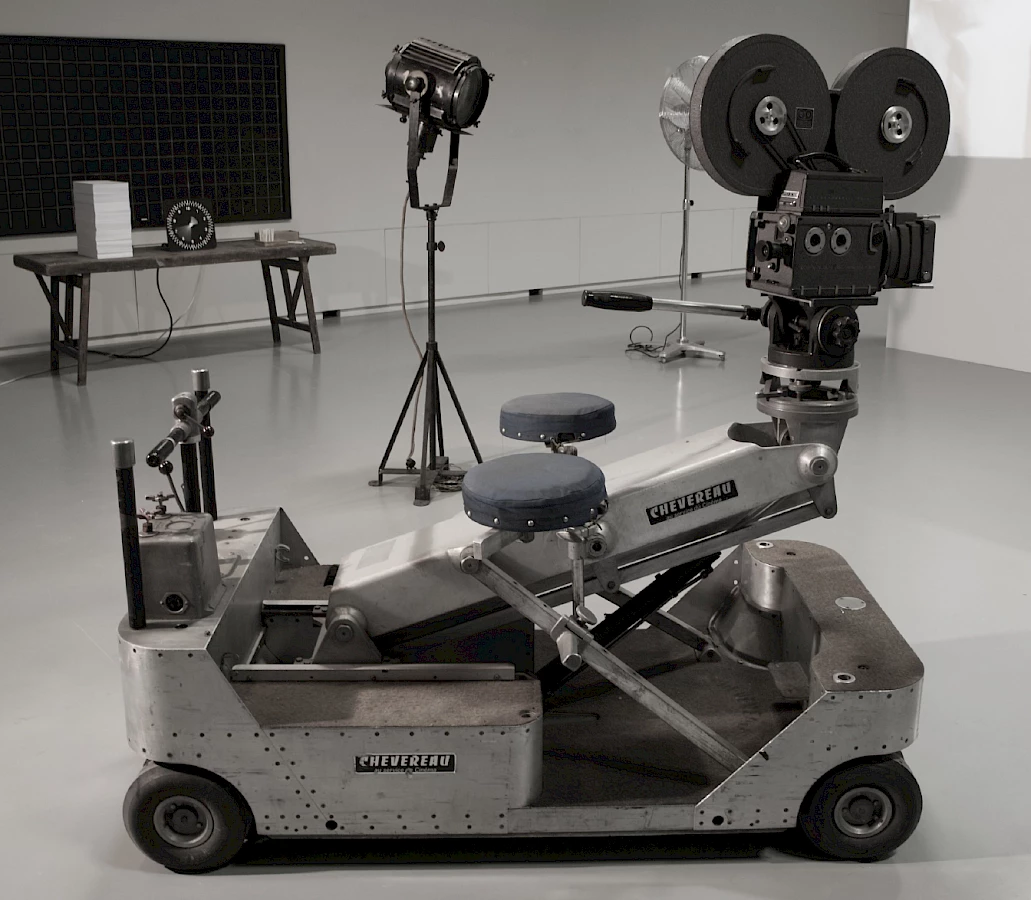

2012 EXHIBITION, Zoë Beloff, The Infernal Dream of Mutt and Jeff, FOMU. Collection M HKA, Antwerp.

2012 EXHIBITION, Zoë Beloff, The Infernal Dream of Mutt and Jeff, FOMU. Collection M HKA, Antwerp.

2012 EXHIBITION, Zoë Beloff, The Infernal Dream of Mutt and Jeff, FOMU. Collection M HKA, Antwerp.

VRIELYNCK COLLECTION #2

Zoe Beloff – The Infernal Dream of Mutt and Jeff

16.02–03.06.2012

Zoe Beloff was the second artist the M HKA invited for an intervention in the Vrielynck Collection. In her work, Zoe Beloff looks for ways of depicting the unconscious processes of the mind. In doing so she tries to connect with the technology of the moving image. The title – The Infernal Dream of Mutt and Jeff – refers to a 1930s Super8 film that she found during her research in the archives of the Vrielynck Collection featuring Mutt and Jeff, two down on their luck characters from America's longest running comic strip. This comical cartoon film is exemplary of the way moving images influences the mind. Industrial and educational films from the 1940s, 50s and 60s provide another starting point for her installation. In addition to a video triptych and a film, which were re-contextualised in an installation that recalls a mid-twentieth century film studio set, Beloff incorporated objects and equipment from the Vrielynck Collection. In a separate area, these audio-visual media were being put into context. By means of a series of drawings, she examined how in the past utopian visions of social progress were linked to film equipment, industrial management and modernism.

2013 EXHIBITION, David Blair, LATT Vrielynck Collection. Collection M HKA, Antwerp.

2013 EXHIBITION, David Blair, LATT Vrielynck Collection. Courtesy: Collection M HKA, Antwerp.

2013 EXHIBITION, David Blair, LATT Vrielynck Collection. Courtesy: Collection M HKA, Antwerp

2013 EXHIBITION, David Blair, LATT Vrielynck Collection. Courtesy: Collection M HKA, Antwerp.

VRIELYNCK COLLECTION #3

David Blair – The Telepathic Place: from the Making of 'The Telepathic Motion Picture of The Lost Tribes'

07.06–08.09.2013

David Blair was the third artist that M HKA invited to interact with the Vrielynck Collection. The basis was provided by The Telepathic Motion Picture of The Lost Tribes, an expansive research project that is like in a flashback to the reconstruction of a lost film production in Manchuria, the doomed epic entitled The Lost Tribes. The media artist David Blair juggled with archive images, animation and live action to create a pseudo-scientific film in which he explored the boundaries between fact and fiction, truth and invention. His intention was to show that history is always a construction that is never definite but always changing and which requires new interpretations. In addition, the project was an allusion to the effect of nostalgia on our consumption of information.

For this exhibition Blair incorporated a large number of objects from the Vrielynck Collection displayed in five rooms and combined this with a series of paintings, assemblages and short video animations from his own archives; they all add to the evocation of the history of The Lost Tribes. A hypnotic soundtrack transported the viewer into the delirious dream of an unhinged archivist, "an infinite universe, a filmic pantheon full of political ideologies that readily dissolve into a non-linear experience of time" (E. McMehen).

A Million Pictures: Magic Lantern Slide Heritage and the Common European History of Learning

Currently M HKA is participating as "associated partner" in the project A Million Pictures: Magic Lantern Slide Heritage and the Common European History of Learning. This project brings together researchers, curators, archivists and artists to develop new ways for people to connect with the history and heritage of the magic lantern and its slides. In collaboration with the University of Antwerp, M HKA will contribute to this project by making the Vrielynck Collection accessible for research, to produce interesting forms for re-using heritage to expand our knowledge and insight on magic lanterns and lantern slides. The museum will also accommodate or co-organise presentations that make the results of this research public. In this way the project will contribute to the development and remediation of the Vrielynck Collection.

–Jan De Vree, Curator at M HKA, Antwerpen

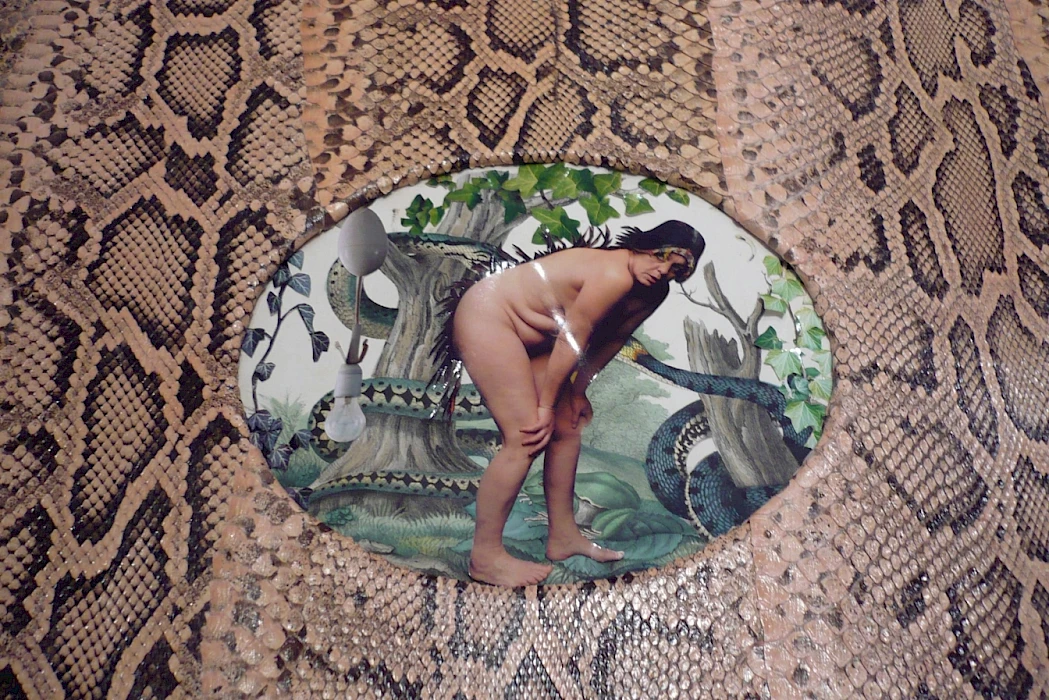

Ines Doujak, Evviva il coltello! (Es lebe das Messer!) [Long Live the Knife!], 2010, performance. Set of scenic elements, consisting of a book and a suit mask carved in metal core, with which you can activate a performance. Metal, textile, paper, snakeskin. Book: 73 × 57 cm / Suit 180 × 43 × 41 cm / Mask 79 × 62 cm. AD05878. Collection of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid.

Ines Doujak, book cover, Reina Sofia Museum collection in 2010, produced by the artist in order to participate in the temporary exhibition The Potosí Principle. How Shall We Sing the Lord’s Song in a Strange Land? Photographers: Joaquín Cortés / Román Lores. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (Archivo fotográfico).

FROM THE COLLECTION OF MUSEO NACIONAL CENTRO DE ARTE REINA SOFÍA, MADRID (MNCARS)

Ines Doujak

Evviva il coltello! (Es Lebe das Messer!)

[Long Live the Knife!]

With reference to Clémentine Deliss' use of the term 'remediation',1the selected work by Ines Doujak (Vienna, 1959) questions the museum and its visitors since it explores the colonial and ethnographic technologies used to shape major narratives, thus triggering an examination of their potential decodification.

From a feminist viewpoint, Doujak's work analyses the bio-political shift in historical-social narratives, often rooted in explorations of the colonisation and primitive accumulation processes that signal the start of modernity and culminate in modern capitalism. The work's title refers to the adulatory words people would shout upon hearing a castrato sing an aria, a highly esteemed form of music in the European colonial period – for nearly ten years, the eminent castrato Farinelli used song to alleviate the depression suffered by Philip V. The expression Evviva il coltello! [Long Live the Knife!] refers to the knife that maimed the singer entrusted with captivating the courts from the old continent.

While the elements that comprise the work can be displayed as an installation, it is through performance that they are ultimately set in motion. In this instance, a countertenor, in attire that conceals his face behind a mask but exposes his stomach and genitals, chants excerpts from the book Confesionario para los curas de Indios con la instrucción contra sus ritos y exhortación para ayudar a bien morir, written during the Viceroyalty of Peru and made public through the Council of Lima in 1585. The book's subject matter was a major instrument in the mechanism of bio-political control exercised over the New World, regulating the body's pleasures and its relationships with nature. The countertenor pretends to read aloud from a book which is covered with snakeskin, a symbol in Amazonian and Andean cultures representing the belief that the world was created from the song of an anaconda. In contrast in Christian culture, the snake is associated with sin, death and destruction.

In Europe and the colonies, female or feminised bodies operated as instruments to produce wealth and behavioural control, while the extermination of indigenous cultures or the acculturation of their peoples was a bio-political process, not just ideological or religious. Doujak formulates an opera from which to confront the "civilising" power of European classical music and the evangelising doctrine, using the sexed and disturbing image of a masked countertenor as a metaphor for muted historical accounts as she places the viewer in an uncomfortable space verging on abjection.

–Lola Hinojosa, Head of Performing Arts and Intermedia Collection, MNCARS, Madrid.

Lenin—Coca-Cola by Alexander Kosolapov and Related Artifacts. Painting, oil on canvas, 1980-2000, objects, publications, film-footage, related to “Lenin” and “Coca-Cola”, various dimensions and materials, 2011. Photo: Dejan Habicht. Courtesy Moderna galerija, Ljubljana.

FROM THE COLLECTION OF MG+MSUM, LJUBLJANA

Lenin – Coca-Cola

by Alexander Kosolapov and Related Artifacts

With the establishment of the first art museum more than 200 years ago, all of the artefacts from the past included in museum collections became transformed into works of art. Even today those artefacts have at least two layers of meaning: one defined by their original purpose (sacred painting, for example), and another acquired in the art museum by being declared as art. Art museums, organising works chronologically and by national schools played a decisive role in establishing the History of Art structured by the same principles. Ever since, all the more recently produced artefacts included in the art museums have been originally conceived as works of art. In other words, all those paintings, sculptures, objects, photographs, collages, ready-mades, installations, performances, etc. that emerged within the field of art museums and art history have claimed one layer of symbolic meaning – to be understood, interpreted and exhibited only as art.

Since it has become apparent in recent years that art is not some universal category but basically an invention of the Western (European) culture, a "child" of the Enlightenment decisively shaped by Romanticism, it might be worthwhile contemplating other possibilities to interpret and exhibit artefacts conceived and treated, until now, as art. One way of doing this would be a gradual detachment from the notion of art and an attempt to look at an artwork as a (hu)man-made specimen, as an artefact of a certain state of mind or cultural/ political milieu. This approach should not be one of a passionate believer and admirer of art, but one that is the diagnostic, almost cold approach of an ethnographer. In order to fully establish this "dispassionate" position, some of the existing art museums would have to gradually transform into anthropological museums about art. These would represent a new kind of museum that would enable the de-artisation of existing works of art into non-art artefacts, the way the desacralisation of religious paintings and objects changed their meaning when they were moved from churches into art museums. Until this (de-artisation) happens, it might still be possible to apply this approach to individual works of art within art museum exhibitions and displays, as in the case we discuss in this instance.

Here is a work of art in the form of a painting by Alexander Kosolapov entitled Lenin – Coca-Cola, dated 1980, in the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova in Ljubljana. Its iconography would be recognisable to most of the public since it is a combination of two well-known and contrasting icons of twentieth century mass-culture. One is a portrait of Lenin (Vladimir Ilich), leader of the first socialist revolution out of which emerged, in 1917, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), one of the countries that most shaped the history of the twentieth century until its demise in 1991. In spite of an early death in 1923, his image, often carried on red banners, has become one of the most recognisable symbols of the international communist movement. Another globally recognised symbol is the Coca-Cola logo, perhaps the most popular soft drink in the world today. First introduced in 1886 in the United States, it is now sold in more than 200 countries and its white letters on a red background have become a central symbol of globalism and consumerism, as one of the ultimate achievements of liberal capitalism. Exhibited here primarily as an artefact, the painting is displayed with various randomly selected objects and film footage from mass culture, related either to "Lenin" or to "Coca-Cola", which are also exhibited as artefacts. They should provide some information on the broader political and cultural context necessary for a better understanding of the iconography behind the painting, the respective symbolisms and the contradiction and irony of merging them into a single image. There is no way of predicting how far into the future Lenin and the meanings of his image will be remembered, nor Coca-Cola as a drink and its logo for that matter; but we could be almost certain that on their slow journey into oblivion the meaning of these two symbols will definitely be transformed in a way we could not anticipate today. When that happens, the original meaning of this painting will disappear, and if it physically survives and finds a new purpose, the painting will acquire an entirely new interpretation. By exhibiting the painting together with other related artefacts, we might, up to a point, prolong the preservation of its original meaning. But in the long run, there is a good chance that even this attempt would have only limited and unpredictable effects.

–Walter Benjamin, Berlin, 2011.

Walter Benjamin is an art theoretician and philosopher who in his article "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" (1936) addressed issues of originality and reproduction. Many years after his tragic death in 1940, he reappeared in public for the first time in 1986 with the lecture "Mondrian '63–'96" in Cankarjev dom in Ljubljana. Since then, he has published several articles and given interviews on museums and art history. His most recent appearance was a lecture "The Unmaking of Art" held in 2011 at the Times Museum in Guangzhou, China. In recent years, Benjamin has become closely associated with the Museum of American Art in Berlin.

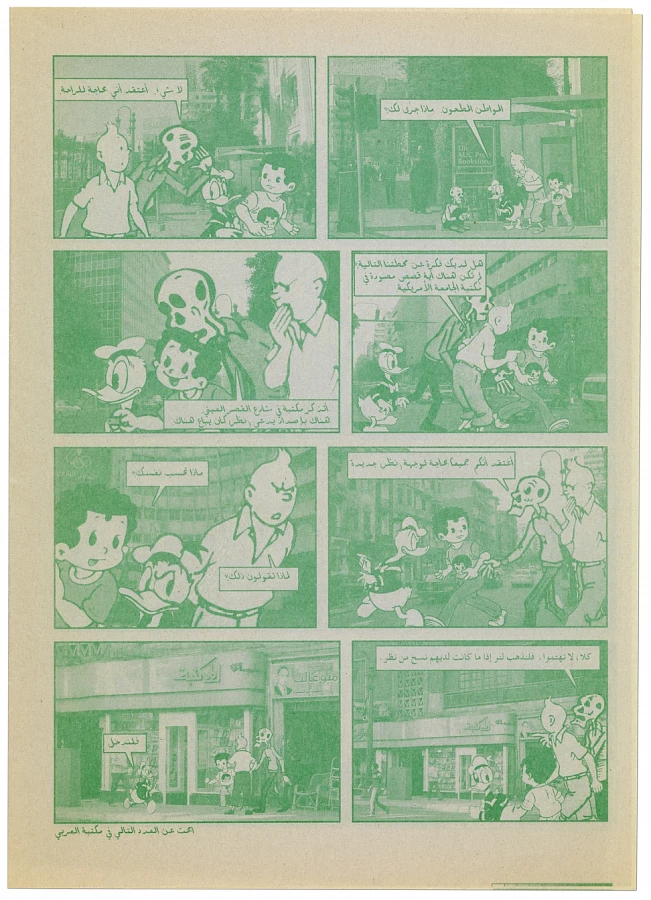

Francesc Ruiz, The Green Detour, 2010. Printed ink on paper 9 four-pages publications, various dimensions. MACBA Collection. MACBA Foundation Photographer: Gasull Fotografia.

FROM THE COLLECTION OF MACBA, BARCELONA

Francesc Ruiz, The Green Detour (2010)

Clémentine Deliss' text "Collecting Life's Unknowns" talks about the potential of the "research collection" and "that it is contingent on experiment and dialogue yet quickly loses its currency. As such it remains oddly outside of market forces yet characterises and punctuates the exploration of the moment." Collections today are situated in this ambivalence. As a museum that collects, it is impossible to disassociate ourselves from the market, while our practice of incorporating artworks into our collection consists in research that contributes to the understanding of a diverse history and evolving present. This research places the collection in a continuous state of change, as the works are subject to the interpretations of curators, to relationships with other works with which they are shown, as well as to the diverse perspectives of each viewer.

The Green Detour (2010) by Francesc Ruiz (Barcelona, 1971), is a nine-volume comic that connects several hotspots of Cairo's city centre and invites readers to literally follow the steps of the characters in the story, with each new instalment providing the coordinates for the following point of distribution. The protagonists – Donald Duck, Tintin, Samir, and 'the Crushed Citizen' – explain emblematic moments in Egypt's cultural history (with references to imperialism, orientalism, government propaganda, and censorship, respectively). As the story progresses the characters move through scenarios with strong political symbolism, question their own status as fictional characters, and wonder whether it is possible to break free from their authors and publishers. This work was produced during a residency at the Contemporary Image Collective in Cairo, where it was exhibited a few months before the mass demonstrations in Tahrir Square.

Using the genre of the comic, Ruiz elaborates works that can be considered site specific because they are always related to the historical and cultural contexts in which they are commissioned. Aware that popular culture is not found in libraries, his fieldwork takes place outside the conventional academic circuits. Contact with informants, visits to flea markets and specialised bookstores, are a few of the research methods that the artist used to understand the history of comics in the Arab world and generate a counter-narrative that resulted in The Green Detour.

In this work, Ruiz relates an untold history with a critical perspective employing the tools of popular culture. In this way, the artist liberates the comic from its traditional popular context and converts it into a critical apparatus. Given its inherent contra-culture nature and capacity for unconventional distribution, the comic becomes a platform for alternative narratives and generator of new debates and emancipatory practices.

Museums today are no longer temples for relics but are flexible entities in a permanent state of transition. The work of Ruiz allows us to explore the intersections between diverse disciplines, recuperate a part of oral history, understand the context of the Arab Spring a few months before the uprisings, discover Cairo through the gaze of another, and other readings that may be generated with time and the constant dialogue with other works in collection. As such, The Green Detour allows for a break with old hierarchies and establishes new ways to define our collections. Deliss described this as "building additional interpretations onto their existing set of references."

"Who can speak about anything in every moment? I am interested in the fact that certain events take place and that whoever speaks about this is not necessarily the person who should speak about this." Francesc Ruiz

ONLINE REFERENCES:

Work currently on display in the exhibition in Desires and Necessities. New Incorporations to the MACBA Collection.

Interview with Francesc Ruiz (28') on Radio Web MACBA:

Part 1 and 2

Interview with Clémentine Deliss on Radio Web MACBA:

Part 1 and 2

RELATED UPCOMING EVENTS AT MACBA:

Workshop with Francesc Ruiz, Sexy comics for all ages (2 December 2015).

Rosoum Project (a collaboration with BCN Producció'15) (23–27 November 2015).

The views and opinions published here mirror the principles of academic freedom and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of the L'Internationale confederation and its members.