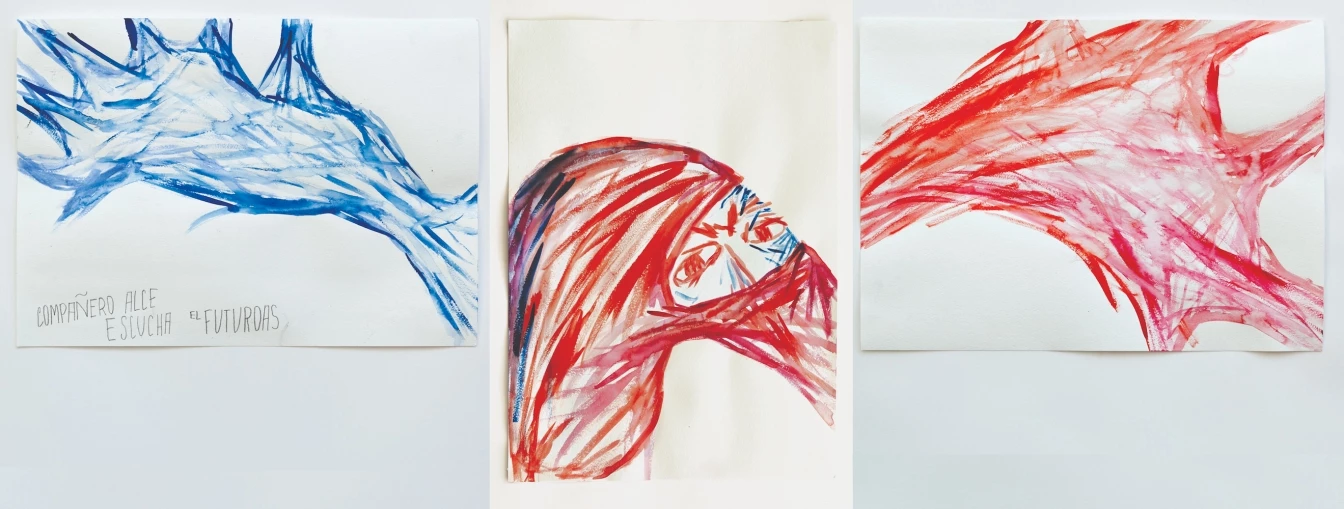

Nikolay Oleynikov (Chto Delat), Comrade Moose, 2021, watercolor on paper. From the series And the Embassy Sails On, 2021. Courtesy the artist and The Gallery Apart, Rome.

I encountered Zapatismo, as it emerged internationally in the mid-1990s, in Milan, where I was a frequenter of the autonomous social centers, some of which were directly involved with solidarity campaigns in support of the insurgent people of Chiapas, whose famous ‘Ya basta!’, declared on 1 January 1994, echoed across continents, reverberating with revolutionary hope among communities engaged in struggle, and militant groups, in the West as well. The vast mobilization of other communities, a part of Mexico’s civil society, and the immediate international response were key elements of the interruption (at least momentarily) of the military repression of the Zapatistas, only two weeks after their levantamiento (insurrection). Since then, the Zapatistas’ maintenance and cultivation of a channel of communication with comrades beyond Mexico has been a key part of their strategy. Widely sharing their vision, processes and struggles, they have aroused trans-territorial attention in moments of danger, generating a vast sense of admiration, and even devotion; challenging and informing our praxis, and inviting our solidarity to manifest unconditionally and on their own terms.

At crucial times – after periods of silence, retiring to protect their processes of building autonomía (autonomy) away from any external interference,1 or going underground in the Selva Lacandona to face the ongoing low-intensity war and counter-insurgency perpetrated by the state, the paramilitary and the narcos – the Zapatistas would reach out with an invitation, generating waves of responses among activists, artists and intellectual circles. Caravans would be organized from Italy (as from many other places), and people would join the Zapatistas in Mexico. This was the case, for example, when a contingent of Tute Bianche (literally, ‘white overalls’) and many other Italian activists participated in the March of the Color of Earth from Chiapas to Mexico City.2 At other times, comrades would collect funds and help to build infrastructure, offering skills or bringing medical aid required in the Caracoles, the Zapatistas’ autonomously governed territories.3 Upon their return home, assemblies would be held to share and report back from that far, fierce, almost legendary world where heroic Indigenous men, women, children and elders, campesinos (farmers) wearing masks to become more visible, kept on declaring their opposition to Empire, to the nation state, to the patriarchal, racist, colonial, capitalist system, reclaiming their land and the right to their own ways of life – to dream their own dreams of a world that contains many worlds.

Murals representing Zapatistas and their symbols of the paliacate (bandana), the balaclava and corn, tagged with their mottos, started to appear in the Italian urban landscape, as fair-trade commerce was organized to distribute Zapatista coffee. Many of our autonomous centers’ infoshops became populated with publications of their literature, mostly of Subcomandante Marcos’s letters, fables and communiqués. Once his books began to circulate, and his mysterious, ‘holographic’ figure and postures (riding a bay horse, smoking a pipe through his pasamontaña (balaclava)) became iconic, together with his fervent, sharp and unique literary style, the Zapatistas’ words permeated our imaginary, resonating deeply between the Italian leftist, antifascist, anarchist legacy, and the traditions of autonomía – linking wor(l)ds of resistance, while offering another necessary perspective; a language full of poetic metaphors, inclusive of many relations beyond those of living human beings. This became progressively evident, and more so during the mobilization of what, within alter-modernity struggles, was called the No Global movement. In 2001, this mobilization tragically culminated at the infamous G8 summit in Genoa, where thousands of peaceful protesters were met with aggression and the young activist Carlo Giuliani was killed by the police. On that occasion, the opening message of the protesters clearly borrowed the language, narrative, form and structure of Zapatista discourse and invocations.4 Now, twenty years after that moment, we have seen how the war of counter-insurgency against life has spread and intensified across the globe, including in the so-called Global North.

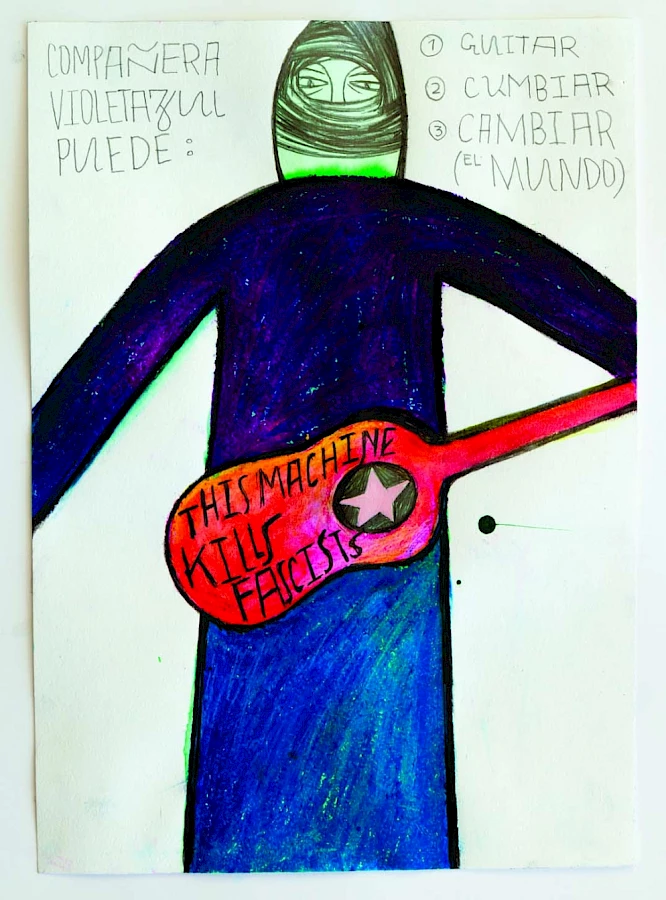

Chto Delat (realized by Nikolay Oleynikov), Flag #1: To Negate Negation (Carlo Giuliani), 2021, mixed media. From the series Navigation Signal Flag System. Set #3: Some Signals Registered from Chiapas, 2021.

In their peculiar way of practicing and enhancing internationalism via a generous literature, the Zapatista both warn and nourish the political thinking of those of us who have started to understand their project of sustained revolution. The Zapatistan conjunction became a lens through which we reflected upon the complexities of the neoliberal and neocolonial organization of the world, and its dramatic effects upon different territories and ecosystems – that which they also name and frame as the Fourth World War.

Zapatismo inflamed our practices, with a ripple-effect rarely achieved by other insurgent groups. With the experience of those who, over the years, would serve as international observers, or participate in the semilleros (seminars), escuelitas (little schools), CompArte or ConSciencia festivals; in the encounters with and between women in struggle; through publications and the constant work of translating, transmitting and building solidarity networks, the dialogue with Zapatismo grew, producing what we like to call a ‘resonance’: not an imitation of their example, which could not be repeated, but a refraction, a reverberation, a listening-with; a collective thinking-feeling through struggles, ‘a habit of assembly’.5

What it means to be in resonance with Zapatismo has now become clearer, both in retrospect and with the new perspective that their visit to Europe opened up, reigniting political energy and transnationally connecting self-organizations. Together with those working politically at the intersection of cultural and knowledge production, in the arts or in education, within and against formal institutions, and with those invested in building community and creating spaces of learning and political mobilization, we ask:

What is the Zapatistas’ lesson? How can we learn with and through Zapatismo, in order to orient our inquiries, to be in service of a larger movement, to repair what has been broken, to remember that which has been forgotten, to position ourselves, to attempt to reverse power, to decolonize our practices and the places we inhabit, maybe preparing to exit them?

Within this frame, and as we live a moment of ecological catastrophe that calls us to produce trans-territorial forms of organizing and a paradigm shift on both a local and a planetary scale, it is worth observing how the wave of Zapatismo reached so many, with different worldviews and knowledge systems; amplifying the possibilities for a locally rooted and globally connected movement. How did Zapatismo become this Northern (Southern?) star, shedding light on the darkest night, offering hope and guidance, even in contexts so different and so far away from Chiapas?

Of course, there is an obvious sense of awe and inspiration that comes from their exemplary practice, their rigorous discipline, their insistence upon truly democratic and horizontal processes, their political cohesiveness, in building another possible world, away from patriarchal, colonial, racist, capitalist ways of life. I am not alone in arguing that the Zapatistas’ usage of art, their poetics, their accessible yet evocative language, has something to do with their ability to successfully transmit their struggle, mobilize affect, and create a wide political awareness and support system. The Zapatista methodology is exemplary: inherently pedagogical and performative, it is concerned with the spread of ideology within the younger generations; the expansion of the skills of each member of the community, and of the spirit of compañerismo (companionship, comradeship, camaraderie), the emergence of a collective subjectivity, to reinforce community belonging – a sense of comunalidad (communality). Their way of being, thinking, knowing and relating is reflected through and built upon a corpus of textual, visual and performative narratives that reinforce, reinstate and celebrate the path of autonomía. The transformation that seems to happen upon meeting the Zapatistas has to do with their unique capacity to inspire and move not only our intellects and our political awareness, but also our hearts and spirit; maybe our own capacities to re-member and connect.

Nikolay Oleynikov (Chto Delat), Compas=Comrades, 2021. From the series And the Embassy Sails On, 2021. Courtesy the artist and The Gallery Apart, Rome.

Twenty-eight years after their uprising, almost forty years after the time spent clandestinely in the Selva Lacandona, the Zapatistas are still resisting and re-existing, and they have a lot to say and to teach us. In the middle of a pandemic, exactly 500 years after the conquest of Mexico by Spanish colonizers, unpredictably, a Zapatista delegation came to visit us in Europe – the first chapter of a journey set to continue on to all the other continents. What did this visit signify? What was the message that they came to deliver, considering they had always invited us to build Zapatismo on our own, in our own territories and with our own tools?

They came to ‘embrace our struggles’, to share their story and to prompt us to commit to defending life. With a sense of urgency, and clearly on a mission to acquire knowledge of, and establish a deeper connection with, those in struggle, their voyage is a call to action; a way to turn around and reach back into history, retrieving those knowledges that have resisted erasure and oblivion. After centuries of defiance and resistance, the Travesia por la Vida is another form of resurgence; an invitation to share a larger struggle, one that unites the people and the lands of the south-west of Mexico with those everywhere else on our planetary home.

During the encounters held in Austria and Italy with activists, farmers, displaced people, and independent journalists (no invitation from governmental representatives or mainstream media was accepted), we were touched by the way in which the Zapatistas recollected their trajectory: a well-prepared and structured narrative, starting with the story of the oppression of their ancestors; a retelling of their Uprising; the various stages of building autonomía, its organization regarding governance, education, health and justice; and the practice of compañerismo – a chronicle collectively shared and diligently repeated upon each different encounter. Within this recollection, the Zapatistas repeatedly acknowledged the support of their compas (comrades) outside of Chiapas, as an important aspect of their resistance. While many of us welcomed them with reverence, they approached us with yet another humbling lesson: a statement of reciprocity; a reminder of our interdependence, the necessity of solidarity and togetherness, the importance of sharing struggles and circulating knowledge about them with mutual respect. They spoke about this relationship as ‘learning with each other’ and ‘building comradeship’ and included copious examples of mistakes and failures, insisting on the necessity of learning from errors and the practice of practicing.

We are seeing seeds of Zapatismo spreading, permeating our soils and blossoming in the cracks of Empire, from center to periphery. The announcement of the gira (tour, journey) the arrival of ESQUADRON 431 on the shore of Spain, followed by the rest of the Zapatista delegation ‘invading’ Europe, to use the language of Don Durito,6 produced a ‘miracle’ – one of coordination, as various organizations in disparate places committed to receive the Zapatistas, took decisions together and co-organized their visits, from August to December of 2021. Aligned, beyond their differences, in a spirit of care and service beyond regionalism, activists previously fragmented and dispersed across the old continent connected to work together; co-managing a crowd-funded budget, finding a common strategy, new protocols and agreements. We witnessed an awakening, as an effervescence of circles and assemblies miraculously formed to co-host the Zapatistas: local, regional assemblies in each country; national ones for each state; and a European one, in close connection with the Commandancia Zapatista – a beautiful, large, slow caracol (literally ‘snail’, ‘seashell’),7 spiraling up in concentric circles, with an opening at its end. It was certainly not without challenges, nor without pain, contrasts and maybe even conflicts; yet a collective moment of fierce care and translocal mobilization did happen – a process the results of which may still have fully to materialize. We prepared for the visit and welcomed the ambassadors from Chiapas with such commitment, a joint effort requiring energy, time, work, finances and other resources. How, then, can we continue to organize together in our many, here and now, prolonging this Zapatista moment?

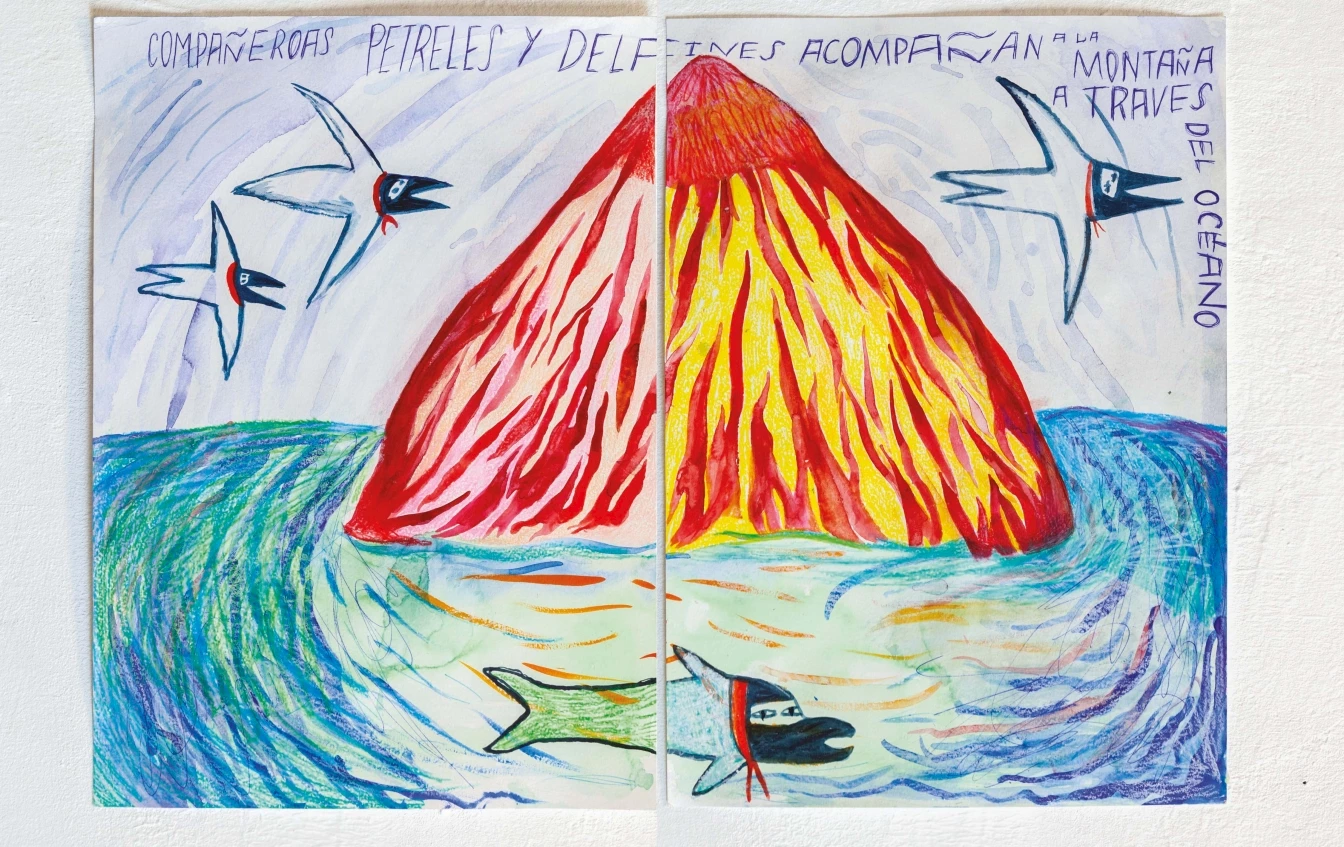

Chto Delat (realized by Nikolay Oleynikov), Comrades Petrels and Dolphins, 2021. From the series And the Embassy Sails On, 2021. Courtesy the artist and The Gallery Apart, Rome.

Notes on Chto Delat’s artistic resonance with Zapatismo

When we first learned about the visit of the Zapatistas, the Russian artistic collective Chto Delat and the Italian group at Free Home University had just completed the film People of Flour, Salt and Water (2019), the second in Chto Delat’s Zapatista trilogy. With many open questions still in mind, we imagined a segue from the film into a book in which to interrogate notions of displacement and belonging. It was within this frame that Zapatismo emerged for us as a form of belonging: a home (or a homecoming) for our hopes and our imaginaries; a belonging that is also a becoming, a desire for the not here yet. When the gira was announced, we expanded the initial chapter on Zapatismo into a larger conversation with some of our comrades from different places, whose contributions are now collected in When the Roots Start Moving: To Navigate Backward, Resonating with Zapatismo (2021) – an editorial collaboration between Archive Books and Free Home University. Invested in politically grounded, collective artistic inquiries and forms of embodied pedagogy, both Chto Delat and Free Home University (with Nikolay Oleynikov belonging to both collectives, bridging people, sites and ideas) consider art a tool for investigating reality; for creating community; for sharing affect and politics. Our hearts beating for the Zapatistas, our visit to Chiapas together provided the common ground for our further collaboration and investigations. Zapatismo was the light we tended to, revealing possibilities for other ways of living, creating space for our own questions, and offering an example from which to drive inspiration and strength – yet without romanticizing or objectifying their movement, their community, their stories or their struggle. And even then, even with all our flaws, we got implicated in this reverberation.

In 2016 and 2017 we shared the life-altering experience of witnessing the Zapatistas’ everyday resistance and re-existence. Our visit to the Caracoles also made evident how hard it is to suspend judgment and avoid the temptation to reduce what we see to what we already know (or think we do), through using the same language, categories and habits of mind we rely on to make sense of the world. The Zapatistas’ widespread, meticulous, capillary-level undoing-and-doing-otherwise troubled and changed our ways of seeing and thinking in manners hard to describe. We were astonished by their deep commitment to organizing just and equitable social infrastructure, where democracy, freedom and dignity are at the center; by how responsibilities are distributed, via the system of cargos, as in shared duties, with power never concentrated in the hands of just a few authorities;8 and by how everyone had a direct engagement in the life of the community. We had to question, scrutinize and rethink our own politics. We had to listen.

The occasion that brought us there was Chto Delat’s first solo show at Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) in Mexico City (2017). The collective initially proposed an investigation into political and artistic connections between the Russian and Mexican revolutions. Eventually, this included the Zapatista insurgency and its influence on activists in post-Soviet Russia. The museum’s curators were skeptical about the relevance of Zapatismo at that point, whether locally or internationally, arguing that the movement was dormant and so probably less politically significant than before. But Chto Delat insisted: they wanted to see with their own eyes. Eventually, they obtained support to accomplish their research.

Chto Delat (realized by Nikolay Oleynikov), Zombie-Communist Team vs. Bird-Girls from Selva, 2017, mural. Courtesy MUAC, Mexico.

Accompanied by Oleg Yasinsky, the very first translator of Subcomandante Marcos’s work into Russian, to help them with both cultural and linguistic translation, they managed to spend time in the Zapatista territories, meeting with researchers, artists, activists and people in the support-base communities. They participated in the assemblies and were even granted permission to interview Subcomandante Moises. Beatriz Aurora, an artist very close to the Zapatistas who contributed to the movement’s striking visual narrative in the early years, was key in introducing Chto Delat to the artists of the CompArte Festival, which led, one year later, to their participation in Chto Delat’s show at MUAC, emblematically titled ‘When We Thought We Had All the Answers, Life Сhanged the Questions’; for the very first time, Zapatista art was included in a museum run by the state and associated with the public university.

Back in Saint Petersburg after their first visit, Chto Delat proposed to the fellows of their School of Engaged Art a study session on Zapatismo. For months, the group read Marcos’s books and studied what they call ‘Zapatista Spanish’, a sensitive, poetic idiom that embodies the Zapatistas’ political vision. To fully grasp the Zapatista cosmopolitics using post-Soviet categories was a challenge: so much had to be rethought again and again, so as not to slip into the fault lines of representation; cultural or stylistic appropriation; the temptation to transpose the Zapatistas’ powerful words and images, or to transform their struggle into an event.

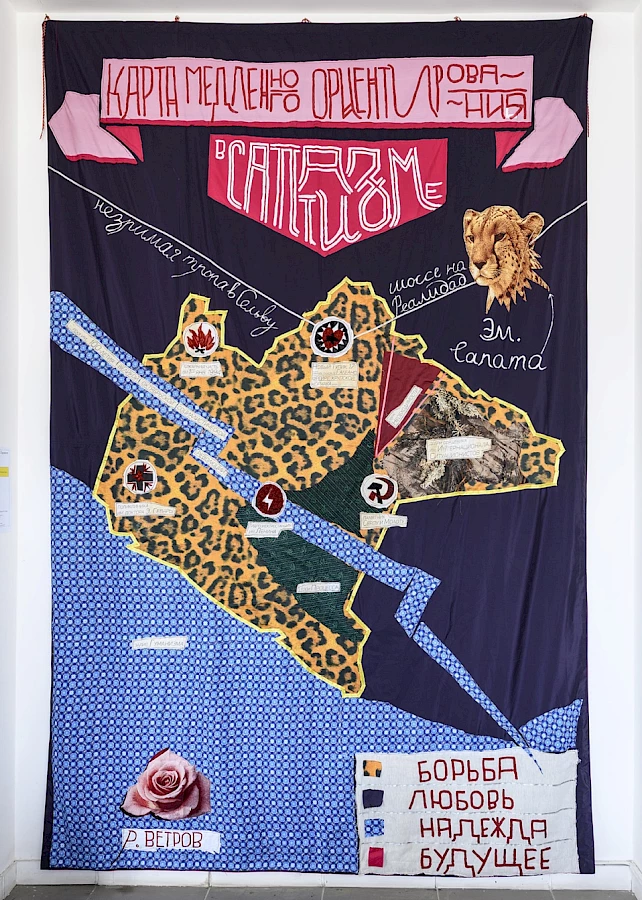

The investigation continued in the form of a ‘learning film’, The New Dead End #17: Summer School of Slow Orientation in Zapatismo (2017), that produced, and was produced by, a collectively embodied process of both living and creating together. The film, as often in Chto Delat’s work, develops on multiple levels: showing the process of creation, narrating the personal stories of the participants, while simultaneously building a fictional story. As spectators, we are carried in a space-time of living-thinking-feeling together, as the group questions the possibilities for Zapatismo in Putin’s Russia; reflecting on what could be translated; readapted to their own struggle; and what type of Zapatismo could emerge in an urban, non-Indigenous context. They imagined (with great intuition, a dream that turned into a premonition) that the Zapatista were coming to establish their embassies in the West. Then, recuperating an old Russian tradition of didactic street art, using the device of a mobile puppet theater, they wandered around a village in the Russian taiga, giving life to critters from the pluriverse of Zapatista fables, or using other puppets to personify their ideas. A year later, Chto Delat returned to Chiapas to share the film in San Cristobal de la Casas, and also at CIDECI, the Centro Indígena de Capacitación Integral, during a multilingual assembly that lasted several hours, with the intention to collect feedback before the final editing of the footage into a montage of separate episodes.

Chto Delat, The New Dead End #17: Summer School of Slow Orientation in Zapatismo, 2017, film still.

Some time after, those encounters produced a new, important moment: the acquisition of Zapatista art pieces by another museum, this time in Madrid – the very capital of the kingdom that conquered Latin America, including Mexico – the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (the Reina Sofía). There, in the summer of 2021, the Zapatista delegation spent time with Picasso’s Guernica (1937), the anti-war masterpiece par excellence, and the director and colleagues in various departments co-organized the Zapatista Forum together with other organizations, including ours. In the exhibition that opened in November of that year (on view until at least 2023) titled ‘Vasos Comunicantes’ (‘Communicating Vessels’), presenting different sections of the Reina Sofía’s collection together with the new acquisitions, the Dispositivo 92 assemblage asks: ‘¿Puede la historia ser rebobinada?’ (‘Can history be rewound?’).

In this part of the exhibition, Chto Delat literally shares space again with the Zapatista artists, in Slow Orientation in Zapatism (2017 – ongoing), an installation that reinstates the magic of their first encounters in Mexico, and their relation of resonance, reception and comradely transmission.9 Here, the Zapatista pieces, three sculpted and decorated canoes and paddles, are juxtaposed with Chto Delat’s video interview with Subcomandante Moises, mounted in the wooden puppet theater used by the artists in their film Dead End #17. In it, quite interestingly, the canoe rowed and steered by backward-facing, balaclava-wearing film participants is a recurring element of many scenes. Maybe this was a fortuitous coincidence, or a lucky transposition. More probably, it was great intuition on the part of Olga ‘Tsaplya’ Ergorova, film director and editor of the group, as it was only after filming that we learned that, for the Aymara people, the canoe represents the cycle of time, and that to reach the future one has to navigate backward, facing toward the past.10 We quote this teaching in the subtitle of our book: When the Roots Start Moving: To Navigate Backward, Resonating with Zapatismo (2021).

As the Slow Orientation in Zapatism continues, and as the museum retransmits ‘the Zapatista signal systems received, to which we respond’ – to use the words of Dmitry Vilensky,11 another member of the group – threads of these old/new constellations appear. It feels somehow significant to trace back this interweaving of people, places, ideas, connections, struggles and actions set-in-motion; manifesting in different spaces and temporalities, through various constituencies. It is also important to note those instances in which museums, as historically and inherently colonial institutions, become pedagogical sites and spaces for encounters that offer occasions to deconstruct colonial narratives, through gestures of repair. In the museum as well as in the university, the intention to rewind (revisit? retell? reframe?) ‘history’, and to correct hegemonic forms of cultural invisibilization, extraction and epistemicide, is an absolutely urgent and necessary trajectory to pursue.

As for the Zapatistas, the acquisition of three of their cayucos (canoes) by the Reina Sofía – something that surprised their more dogmatic followers and was celebrated by those who believe that European museums can and should make space for other worldviews – provided a further opportunity to articulate their politics. The Zapatistas announced their will to donate the anticipated 25,000 euros offered by the museum, which they called an ‘incomprehensible’ compensation, to Open Arms, a Spanish NGO that rescues migrants in danger in the Mediterranean.12 It’s clear that such a sum could have benefited the infrastructure of their communities, yet the gesture (certainly a collective decision) is in line with their pursuit of navigating and undoing the system. They engage in a relationship with the state museum for the sake of building bridges, but then show themselves ready to exit the tentacular mechanisms of capitalism, by re-routing the financial transaction.

When we speak of decolonizing the museum, when we criticize how art has become co-opted by the financialization of the art world, when we invoke a post-capitalist future with a rethinking of international solidarity… the Zapatistas seem to do it all.

Nikolay Oleynikov (Chto Delat), Prof Corn – Queen of the Fields, 2017. From the series And the Embassy Sails On, 2017. Courtesy the artist and The Gallery Apart, Rome.

Once one starts to think-feel with Zapatismo, it is forever. During the 2019 Free Home University summer session, Chto Delat realized their film, People of Flour, Salt, and Water (2019), the second in their Zapatista trilogy. Here too, Marcos’s fables and the Zapatistas’ thirteen demands were deployed to open a conversation about struggles with migrant subjects, war survivors, land defenders, organic farmers and young activists trying to make sense of the world. Here we are in the South of Italy, among hectares of dying olive trees attacked by the Xylella fastidiosa bacteria as their immune system is weakened by extensive monoculture, the use of chemicals and consequent loss of soil biodiversity. But we are also in a territory re-baptized ‘Salento Zapatista’ by the activist Christian Peverieri, invited to join our session to share his experience in the caracoles and the relation between Italian social movements and Zapatismo. It is here in Salento that Casa delle Agriculture was formed by some young activists who came back to the land of their grandfathers, generating a community of practices around natural farming and the communalization of lands and means of production, experimenting with forms of community-supported agriculture (and whose example is now followed by many in the region). Their struggle against agribusiness, the use of chemicals, the privatization of seeds and the new forms of slavery and exploitation, of both labor and land, has been affirmed through educational activities, participatory events, ongoing research and campaigns, as well as the gatherings, celebrations, art festivals and residencies program that Free Home University has contributed to since 2014. All of this was also what intrigued Chto Delat, contributing to their proposing a learning film process here, as they felt a resonance with the campesinos from Chiapas and their milpa (literally ‘maize field’, cultivation plot).13

As artists and film-makers Silvia Maglioni and Graeme Thomson have observed:

Chto Delat describe [this] work as a learning-film. But who is the subject and what is the object of this learning?

One has the impression that the learning process not only involves those who take part in the collective experience but questions the very concept of what constitutes research, a film, a production. While there are clear echoes of the Dziga Vertov Group and a kind of Brechtian pedagogy, at the same time, the film travels far beyond their mock-stentorian classroom mode. Though ludic in its approach, it becomes a transformative experience for those involved and for the camera, which is affectively always with the people in a process within which the viewer, too, can learn.14

Chto Delat, Learning Station #2, Free Home University / People of Flour, Salt, and Water, 2021. Fragment of the installation New kinetic melodies: on miracles, disasters and mutations for the future, 2021. Photo: Giorgio Benni. Courtesy the artists and The Gallery Apart, Rome.

Chto Delat’s third Zapatista film, About the footprints, what we hide in the pockets and other shadows of hope (2020) is a recounting of a public performance and a learning process led in Greece by Chto Delat with the Solidarity School of Piraeus, a volunteer-based initiative that supports migrants and asylum seekers. The artists proposed a selection of texts by Subcomandante Marcos to the participants and their teachers, as tools to learn Greek with; of course, they all learned a lot about Zapatismo, too. During the session, the group was visited by Stavros Stavrides, an activist, urbanist, writer and professor at the School of Architecture in Athens, who shared about the solidarity actions organized and undertaken by Greek activists in Chiapas, including the building of a school. He underlined how the relation between movements opened up a new space for thinking and learning about autonomy and translocal anti-capitalist struggles, both in material ways and on the level of the political imaginary. A local master puppeteer, Stathis Markopoulos introduced the group to the tradition of shadow theater, and the voice of Durito, the famous beetle who appears in many of Marcos’s fables, explaining the fundamental ideas of the Zapatistas, was integrated into the performance that resulted from this process, along with personal stories of the participants’ coming from different countries to live in Greece. As curator iLiana Fokianaki writes:

For the current conditions of Greece, with a government that is introducing a police state, has increased extraction and fracking, and is abolishing the last remnants of a meager welfare state, all while being openly anti-LGBTQI+, anti-feminist, and anti-migrant – the words of the Zapatistas seem necessary. How will they be perceived by migrant communities that struggle to survive in an increasingly racist society? … How can we think of life in a harmonious coalition with Land and Earth? … What is the role of culture in a process of liberation – and how much agency can art have when assuming the role of the vehicle (or the toolbox) towards ideological emancipation?15

The relation of being-in-resonance with Zapatismo that Chto Delat collectively practice – a reflecting-with, a call-and-response, perhaps an echoing, or a reverberation of questions across completely different contexts and geographies – is clarified in their text ‘Unlearning in Order to Learn (with a little unseen help from the Zapatistas)’.16 Here too, they underline, they don’t seek to imitate, replicate or appropriate the Zapatistas’ art and lexicon, but rather to open conversations with it, using it as a lens to self-reflect and to instigate a dialogue with those fighting against or suffering from various forms of oppression. This is evident in all the films in the Zapatista trilogy (as in all of the copious productions in and through which they have engaged with Zapatismo), in which the medium becomes a dispositif that allows a process to happen, and at the same time, to be witnessed and aesthetically formalized. Zapatismo is, in their work, a proposition: almost an ice-breaker, to speak about different struggles; a way for us to check in and exercise our own values and capacity for transformation; a way to reimagine what world we want to live in, and how we can organize to make it possible. Art, on the other hand, is a tool that brings people together; in which new scenarios can be imagined, articulated and tested, and new forms of collectivity can come to life, however temporarily.

Nikolay Oleynikov (Chto Delat), Compas=Comrades from the series And the Embassy Sails On, 2021. Courtesy the artist and The Gallery Apart, Rome.

Through the various processes and investigations that led to these productions, Chto Delat have come to identify what they call a ‘Zapatista method’, a series of principles and guidelines that they transpose into their art-making approach, which is always a process of building of community, a rather porous and rhizomatic one, and an exercise in political prefiguration. This is well explained by Chto Delat member Olga ‘Tslapya’ Egorova, whose witty text ‘Making Films Zapatistically’ shows how profoundly the group’s artistic methodology has been influenced by Zapatismo.17 Their work, openly shaped by Brecht, Godard and Russian art history, has become imbued with the notorious Zapatistas’ anticlimactic and ironic tone; populated by animals and other critters, as well as by visual and lyrical elements that are not just quotations or references, but formal devices among the many visual, somatic, theatrical, political and didactic tools that the collective has developed throughout its eighteen-year existence. Within their practice, these are not only artistic tools but (with Ivan Illich) tools of conviviality, and instruments for building social infrastructure – comunalidad y convivencia (communality and co-living, or better a ‘living with’).

What does it mean to be Zapatista outside of Chiapas?

This was a recurring question that, for a long time, swirled in our head. It was Subcomandante Moises who provided an answer: To fight! To never give up! Never surrender! Never sell out! Never corrupt! At whatever cost, to liberate this world – this is to be Zapatista! – this is to be Zapatista!’18 This is how we keep moving on the foggy road, caminando preguntamos, asking as we walk, as the Zapatista star illuminates our path.

Chto Delat (realized by Nikolay Oleynikov with SHVEMY sewing cooperative), Map of Slow Orientation in Zapatismo – Paris version, 2017, mixed textiles (sewn), vinyl paint, 300 x 200 cm. Photo: Giorgio Benni.

‘Autonomía’ for the Zapatistas is a political process of self-government in which they have engaged ever since their insurrection in 1994, when they declared war against the state, and their exit from capitalism and patriarchy. Refusing the mal gobierno (bad government) brought about by representative democracy, they oppose it with an assembly-run decision-making process in which the assemblies, or Juntas de Buen Gobierno (Councils of Good Government), delegate groups whose rotating members manage tasks of governance for the community. Autonomía is a never-ending project, an ongoing process of pursuing autonomous living, a trajectory that nevertheless has, in their experience, manifested through quite an effective system of self-governance. The term is shared by other leftist circles, anarchists, libertarians and Indigenous people that reclaim their right to their own forms of life, independently of State, Empire and Capital.

See, for example, Chiapas Support Committee, ‘The March of the Color of the Earth’, 20 March 2021, available at chiapas-support.org (last accessed on 17 October 2022).

‘Caracoles’ literally translates as ‘snails’, ‘shells’, ‘conches’, or ‘spirals’, all of which symbolize traits of Zapatismo such as slowness, the circles of their assemblies, the open-ended process of autonomía, and so on. Specifically, ‘Caracoles’ also indicates the autonomously governed municipalities, or regional seats, of the Zapatista government, formerly known as Aguascalientes. There are now twelve Caracoles, administrative centers that govern by applying the seven principles of Mandar Obedeciendo (ruling by obeying) through assemblies and their autonomous systems of education, economy, health and conflict resolution. See ‘Palabratorio’, in When the Roots Start Moving: To Navigate Backward, Resonating with Zapatismo (ed. Alessandra Pomarico and Nikolay Oleynikov), Archive Books and Free Home University, 2021, p. 235.

See Christian Peverieri, ‘Travel to Salento Zapatista’, in When the Roots Start Moving, pp. 141–42.

Manuel Callahan, in conversation with comrades and friends at one of the online Testing Assemblies organized during the 2020–21 Covid-19 lockdown.

Don Durito is a fabulous beetle, quoted by Subcomandante Galeano when he announced the tour. See Subcomandante Marcos, Conversations with Don Durito, New York, Autonomedia 2005, available at schoolsforchiapas.org (last accessed 14 October 2022).

Cargos, literally ‘weights’, ‘loads’ or ‘charges’, are responsibilities given by the assembly to a few (rotating) members of the community, who have to serve by volunteering for these tasks. In reciprocity, the community helps support the family of those charged with the duty, providing food or working on their milpa (literally ‘maize field’, cultivation plot; see also fn. 16). The system of cargos draws on traditional Indigenous forms of organizing leadership and authority that are strictly connected to a sense of service to the community, rather than power over it.

See Chto Delat, ‘Slow Orientation in Zapatism: When we Thought we Had all the Answers, Life Changed the Questions #2017’, chtodelat.org (last accessed on 23 September 2022).

Dmitry Vilensky in Episodio 7, Dispositivo 92, Puedes la historia ser rebobinada, 2021 (digital video interview), available at museoreinasofia.es (last accessed on 3 October 2022).

Sam Jones, ‘Mexican rebels donate museum money to refugees’, The Guardian, 12 September 2022, available at theguardian.com (last accessed on 18 November 2022).

The milpa is the basic system of ancestral cultivation in Mexico. Corn is grown with herbs and fruits such as epazote, chili peppers, squash and beans, creating a micro ecosystem for mutual collaboration and protection from pests. In Zapatista territories, there is a collective milpa for the community and a smaller milpa for each family.

Silvia Maglioni and Graeme Thomson, ‘The Fate of an Insect that Struggles Between Life and Death Somewhere in a Nook Sheltered from Humanity is as Important as the Fate and the Future of the Revolution’, in When the Roots Start Moving, pp. 129–30.

Chto Delat, ‘Unlearning in Order to Learn (with a little unseen help from the Zapatistas)’, When We Thought We Had all the Answers, Life Changed the Questions, Mexico, MUAC, UNAM/CAAC (2017), available at chtodelat.org (last accessed on 23 September 2022).

Olga ‘Tslapya’ Egorova, ‘Making Films Zapatistically’, in When the Roots Start Moving, pp. 193–99.

Subcomandante Moises in conversation with Chto Delat and Oleg Yasinsky, transcribed in ‘The knowledge of the struggle, and the struggle of knowing’, in When the Roots Start Moving, p. 72.