Emerging Innovative Artistic Practices as a Response to the State of Siege

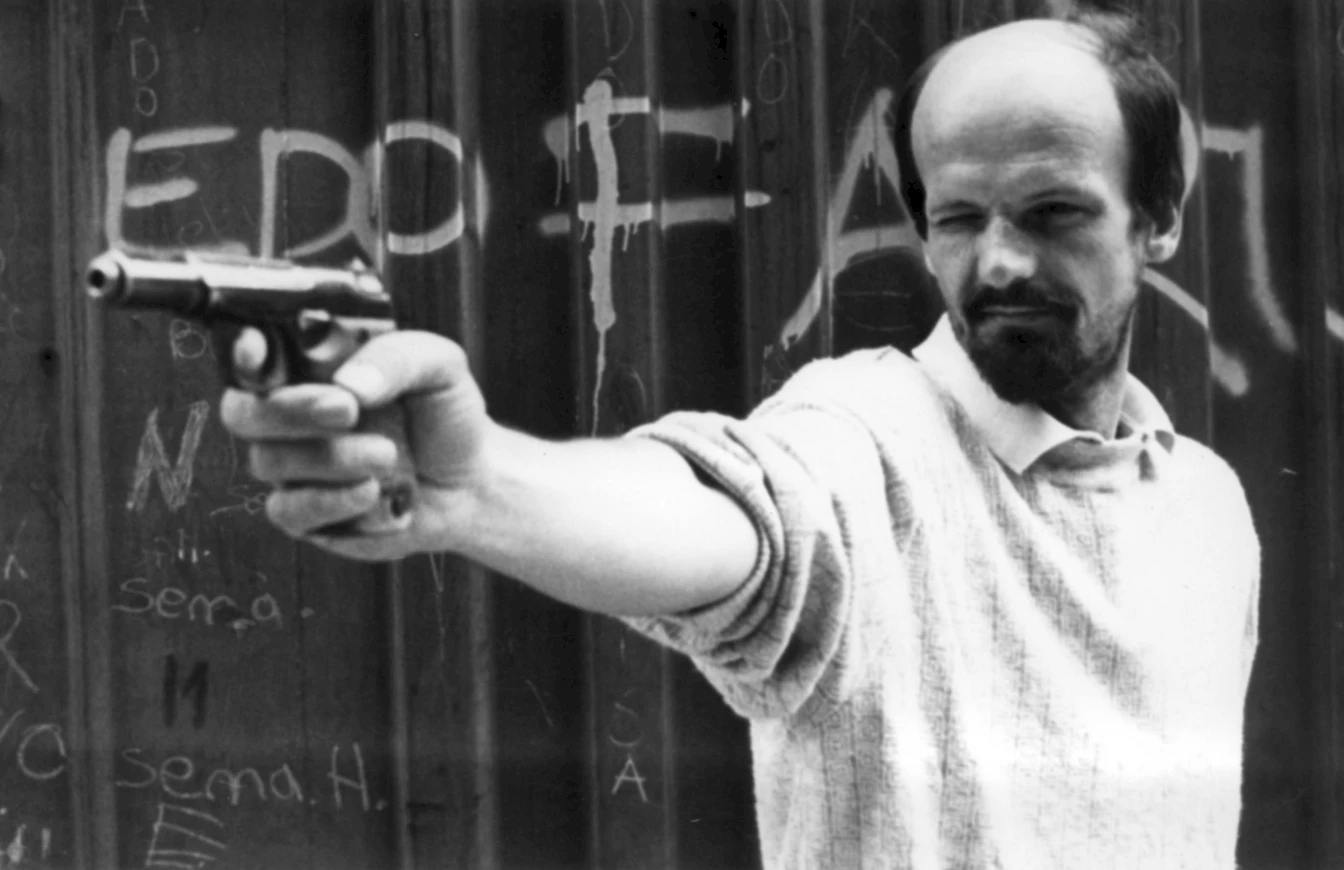

Xeroxed photograph of Pregrad Čančar’s documentation of performative action May 15, 1992 (artists Zoran Bogdanović and Ante Jurić) with Jurić’s textual intervention. Source: War Art Diary of Ante Jurić (1992–1994), archive of the Art Gallery of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Courtesy: Ante Jurić and Art Gallery of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The siege1 of Sarajevo (1992–96), often referred to as the longest siege in modern history, manifested as carefully orchestrated violence against the built environment and those who inhabited it during the military-strategic control and paralysis of the city, transforming their everyday lives in ways that seemed unimaginable at the end of the twentieth century. Nevertheless, in this defenceless and vulnerable city – enclosed, cut off, reduced to bare survival and constantly exposed to death – a persistent and defiant spirit of resistance was created that was particularly evident in the sphere of culture. There was a proliferation of theatre performances, concerts, film screenings and art exhibitions, and an increased participation in cultural life which was often perceived as a form of resistance in itself, as people consciously decided to risk their lives to attend events and so to continue with normal life or, we might say, to create that illusion, even under the conditions imposed.

Theatre played perhaps the most important role in this context, with plays performed on a daily basis.2 But the visual art scene also flourished, as about a hundred solo exhibitions and dozens of group shows were held in various locations within the city, including versatile non-exhibition places and ruins. The exhibitions, especially the openings, became sites for gathering and communication; locations for interaction, dialogue and exchange, or places where social space was produced; where artists, cultural workers and visitors became active participants in the processes of cultural resistance and opposition. For local artists, working mainly in traditional media, the new conditions imposed by the siege brought to the fore new strategies. The lack of materials and spaces in which to produce and exhibit their work necessitated adaptations and new approaches to their established ways of working. In relocating and reconfiguring the display of their works, and in re-examining object-based practices in response to the new circumstances, they became more experimental, performative and installation-based, as well as more socially relevant. This essay examines these artist-led actions and curatorial practices, site-oriented or site-referenced interventions in the urban fabric that moved beyond the confines of the art world, as moments of rupture that broke down barriers between social and aesthetic orders and overcame the formerly entrenched approaches and structures of institutional art spaces. The discussion focuses on progressive, experimental events that took place in destroyed and damaged buildings or brought art into open public spaces, as ‘situation-specific’ initiatives here examined as tactics of opposition.3 However, in order to understand their significance as determined by ‘the impetus of place, locality, time, context and space’,4 as well as their sociopolitical potential to respond directly to the forms of control and oppression imposed, it is important first to reflect on the physical, sociopolitical and psychological aspects of the siege, and of bodily resistance to the murderous war-machine.

The Siege of Sarajevo

In the first months of war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo was encircled by the military forces of the Bosnian Serbs, assisted by the heavily armed Yugoslav People’s Army as well as Serbian and Montenegran paramilitary troops. Immobilised, blockaded and subjected to the strategic disruption and destruction of its urban fabric, including of the infrastructure that allows modern life to exist, the city resembled a ruin; ‘enduring between persistence and decay’.5

The state of siege reduced the citizens of the closed and isolated city to a struggle for bare survival, without water, heat, electricity, or food. They were surrounded at all times by the heavy artillery and snipers whose omnipresent gaze controlled their lives and deaths, operating to discipline and punish the body, much like Foucault’s panoptic function of power.6 This controlling gaze came not solely from the outside, from the Olympic mountains and hills surrounding the city, but also from the inside, from occupied Grbavica at its core.7 Ever alert, the gaze of the sniper was inscribed in Sarajevo’s urban body as the control mechanism of behaviour, space and movement. It was present in each of its segments and internalised in the bodies of its inhabitants. Punishment was mostly carried out on those bodies that dared to move within the areas of constant surveillance in the snipers’ field of vision – intersections, squares, bridges – or to group, gather, interact and communicate, to get involved in the processes and situations that make up the essence of the urban.8

The discipline and punishment of the city and its inhabitants, however, differed from the panoptic perfection of power since it was not imposed to the point where the complete disruption of the behaviour of, and of communication between, the controlled subjects was realised. Rather, this particular form of panopticism exemplified Foucault’s ‘functional inversion of the disciplines’ because the power structure that circumscribed the place, aiming to control relations among its targeted subjects, in fact produced oppositional practices.9 Such practices could be described using Michel de Certeau’s notion of tactics, for they subverted the modes of subordination through ‘isolated actions’ that challenged the strategies of surveillance and control.10 According to de Certeau, tactics are operations of weak but active agents that disrupt the strategic ordering and control of the everyday life.11 Considering the nature of the siege of Sarajevo, everyday activities such as walking, searching for food, water or wood for cooking and heating, could be described as tactical in character because they also included the invention of new navigational routes through the oppressed urban space. For the spatially and temporally isolated city, marginalised and deprived of communication with the outside world, artistic practices whose unpredictable momentary actions and interventions in open public space, including manoeuvres ‘within the enemy’s field of vision’,12 were particularly significant tactical practices for opposing and resisting the mechanisms of repression, isolation and social conditions imposed, reviving the city’s sense of urbanity and improving quality of life.

Resisting Bodies: Artistic Interventions in Public Spaces and Ruins

The first artists who replaced their studios with the street and engaged in one of the most radical performative actions were Ante Jurić and Zoran Bogdanović, who consciously exposed their bodies to the agents of surveillance and punishment and defied the strategic practices of the panoptical machinery. Their action of collecting and rescuing remnants of the Central Post Office (one of the most beautiful Viennese Secession buildings in Sarajevo), after it was set on fire in a military diversion on 2 May 1992, took place at the intersection of two streets that lay directly in the snipers’ field of vision, one of which continues over the Čobanija Bridge to the other side. In this action, entitled May 15, 1992, they engaged in pulling and collecting burnt wooden beams, debris and fragments of destruction from the heaps of rubble while Predrag Čančar photographically documented their action. Thus, through the means of their bodies the artists confronted the panoptic spatial order, bringing to the fore that which had been repressed and destroyed. Čančar’s fixing of moments of this lively process was not external to the work; the photographer was inside of the action, himself an active participant in the subversion of panoptic power, as his moving body and his camera also consciously performed for the ‘eye of the spectator (killer/sniper)’ that was monitoring the space of their movements.13

From today’s perspective, it is not clear if Jurić and Bogdanović intended to display the photographic record of this provocative and radical action in exhibitions or catalogues, as something to be seen by audiences afterwards. Nor is it clear if the artists perceived it as live art/performance, or just as a process in which the sculptural material created by an act of destruction was collected for exhibition. The documentation was only ever exhibited in the context of the work of Čančar, in an installation commemorating the vandalistic destruction of the beautiful post office building. Unfortunately, these photographs can no longer be accessed; they subsequently disappeared from the archive of the Art Gallery of Bosnia and Herzegovina, where Čančar worked as a photographer. A fragmentary record of the action May 15, 1992 can still be found in Jurić’s War Art Diary, consisting of the artist’s collection of sketches, personal documents, letters and newspaper clippings, along with Xeroxed copies of (Čančar’s) photographs of the action complete with the artist’s own conceptual, textual interventions.

Predrag Čančar, Post Office 2 May 1992, 1992, Spirituality and Destruction exhibition, St Vincent Church, Sarajevo, 1992. Photo: Milomir Kovačević.

For Jurić and Bogdanović, sculptors who before the war had worked within institutional confines, taught at the Academy of Fine Arts and exhibited their works in official gallery spaces, the use and performative transformation of street spaces into working spaces and galleries brought new approaches to the fore in their practice.14 The effect of the temporality of their presence in these new spaces, where the aesthetic qualities and formal limits of their object-based works were inevitably challenged, was to move them towards the dematerialisation of their art.

The intention of these two artists, who prior to that point had worked in their area of competence, holding true to the aesthetic autonomy and formal qualities of the artwork, had been to collect authentic sculptural material and exhibit it in a gallery setting. However, their exhibition entitled ‘Spirituality and Destruction’ (1992), in which Čančar’s installation composed of the photographs of their action was also included, actually took place in the interior of the damaged Church of St Vincent de Paul. Even though some of the exhibited works, created from the remnants of destruction at the Academy of Fine Arts, were directed by the Modernist conception of the artwork, that is, that of Art Informel, the physical conditions of the damaged church interior directed them, quite spontaneously, to find alternatives to Modernist art and its usual, institutional setting. Bogdanović’s ‘Art Informel-type relief drawings’, made of embers, broken pieces of glass and sand glued onto paper, were now placed on the scarred church walls.15 Juxtaposed with the scorched beams, shards of metal structures and various other kinds of rubble from the burnt-out Central Post Office, together with spatial interventions by Jurić that highlighted the physical conditions of the damaged Catholic church (wrapping the church altar in white sheets, sweeping the dust and fragments of broken stained-glass windows), the works established meaningful relationships with the site, by which they became formally directed and determined, framed by its environmental context. Transformed into a temporary exhibition space, the church became a point of departure revealing its physical, social and political context.

Spirituality and Destruction, exhibition opening, St. Vincent Church, Sarajevo, 1992. Photo: Milomir Kovačević.

These artist-led, spontaneous, ad-hoc, time-based initiatives challenged not only the modes of display practiced in institutional gallery spaces in Bosnia and Herzegovina before the war, but also the prevailing art practices that, prior to the war, had been limited to traditional media. But while they did bring to the fore anti-establishment, anti-institutional approaches, this is not to suggest that they acted wholly in opposition to the mainstream since, in need of validation for their work, the artists invited Azra Begić, curator of the Art Gallery of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Sadudin Musabegović, dean of the Academy of Fine Arts, to write texts for their ‘Spirituality and Destruction’ exhibition. Furthermore, Begić delivered the exhibition’s opening speech. Thus, the dislocation of their practice from pristine gallery spaces into spaces of destruction came rather from a need to respond to the destructive machinery of war, or, in the words of Jurić, to ‘present the reality … and document prevailing destruction’.16

Ante Jurić, Sarajevo Shot, 1992, Courtyard of the Academy of Performing Arts, Sarajevo, 1992, Courtesy: Archive of the Obala Art Centre.

A work that similarly responded to mechanisms of violence and repression, but that was foreign to Jurić’s practice up to that point, was his performance Sarajevo Shot, conceived of in reference to the 1914 shooting in Sarajevo of Gavrilo Princip and directly evoking this historic event as a warning ‘to the world, of the potential danger of a new Balkan World War’.17 Though he re-enacted it several times, the first performance took place in November 1992 in the courtyard of Sarajevo’s Academy of Performing Arts, where Jurić fired several bullets from a pistol at a tin surface supported by sandbags.18 The second enactment of this performance was planned to take place at the actual site of the 1914 ‘Sarajevo assassination’, but in the event it was too dangerous. While it is true that in his writings, sketches, drawings and elaborations of artistic ideas one can still find a preoccupation with the ‘aesthetic process’ – that of materials and their transformation, in which performance can be seen as a process of object creation or as ‘a phase of real creation’, after which ‘an object with memory of an event remains’ – this work clearly indicates Jurić’s de-emphasis of sculptural concerns and his journey towards the dematerialisation and de-aesthetisation of art.19

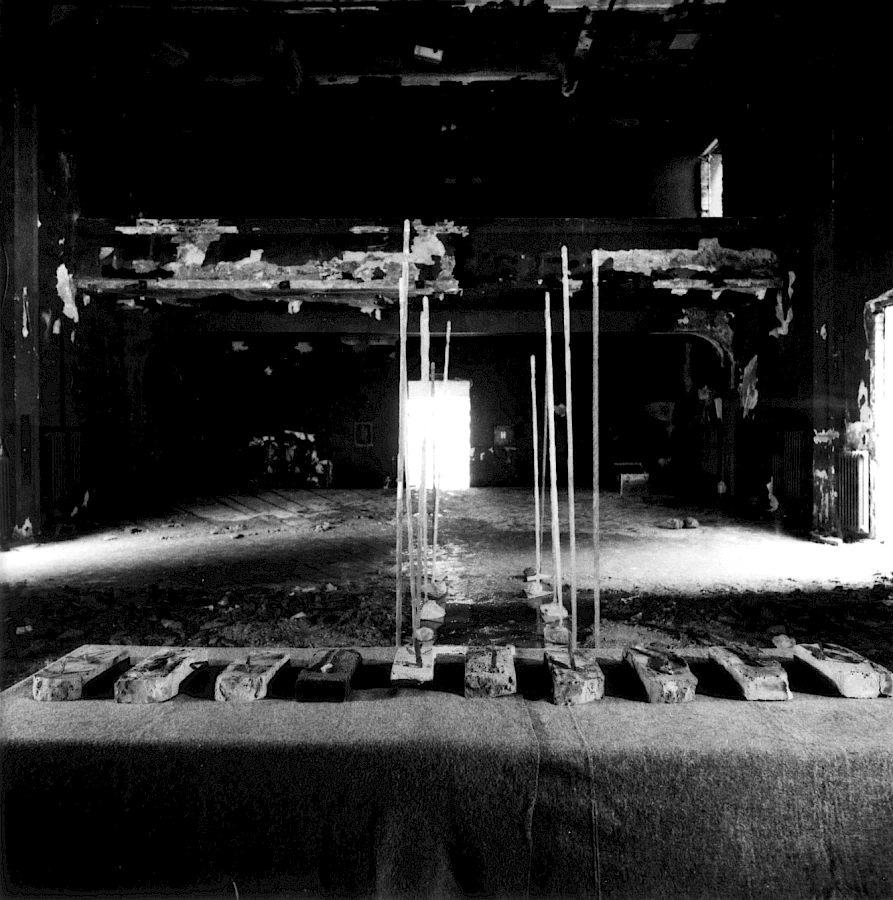

Ante Jurić, Muddy-Edged Form Leaning on White Canvas and the Wall in a Ruined Space of Sutjeska Cinema, 1993, Sutjeska Cinema, Sarajevo, 1993. Courtesy: Archive of the Obala Art Centre.

Just few months after the exhibition at the Church of St Vincent de Paul and after the enactment of his first performance, Jurić created a work that was bound to the materiality of the site. His installation Muddy-Edged Form Leaning on White Canvas and the Wall in the Ruined Space of Sutjeska Cinema, made for the ‘Spirituality – Destruction – Rematerialization exhibition’ (1993) in which Bogdanović also participated, was clearly a site-specific work, its identity composed of a unique combination of physical elements: the shape, length and texture of the damaged walls, along with shovelled debris and dirt.20 ‘Spirituality – Destruction – Rematerialisation’ was just one of the exhibitions organised by the Obala Art Centre between December 1992 and March 1993 in the devastated Sutjeska Cinema, which had reached the final phase of its renovation and transformation into the Obala Open Stage space just before the war began. In fact these events, presenting the work of Nusret Pašić; Zoran Bogdanović and Ante Jurić; Mustafa Skopljak and Petar Waldegg; Sanjin Jukić; Edin Numankadić and Radoslav Tadić respectively, were closer to temporary interventions than they were to exhibitions in the classical sense. Each usually ended after the opening, when the artists would remove the works to protect them from rain, snow, and further decay in what remained of the building. The devastated space of the former cinema therefore functioned as intended, as an open stage, but one where artists intervened in the very substance of its ruin with their works and installations, interacting and communicating not only with exhibition-goers but also with passers-by because the desolate cinema, located on one of the most dangerous intersections, was used as a passage that sheltered people from the sniper’s gaze.21

Situating exhibitions in such places thus created spaces of public interaction and participation in which spatial, bodily experience was extremely important to the overall experience of spectators (though not necessarily of equal, individual importance to each of the works shown). It was this interactive ‘phenomenology of Presence, a spectatorship that unfolded in “real time and space”’,22 which gave these artistic/curatorial practices a ‘theatrical quality’, as defined by Michal Fried, through the emphasis of ‘stage presence’, or the condition in which objects/bodies were placed in situations.23 The idea of an exhibition’s own performativity may certainly be applied to ‘Witnesses of Existence’ (1993). A group show that reunited the eight artists in the same space, it was itself conceived as scenography ‘for a series of performances assembled into a theatrical whole’.24 There, highlighted by spotlights and sound, the artists successively and dramatically revealed their presence in the darkness, achieving stage effects for their works and their own bodies.25

In relation to the space, its audience and the duration of their experience, the exhibitions held at the ruined cinema corresponded to its condition and effects of ephemerality, transience and flux. In places so subject to the contingent, artists’ works themselves could only be seen as temporary spatial situations – works such as Kemal Hadžić’s Sarajevo Caryatids (1995). In 1995, these photographs of beautiful young Sarajevan women, each leant against a burnt pillar of the National and University Library, were exhibited in the scorched ruins of the library itself, accompanied by a performance by ballerinas from the National Theatre. Before it was brutally destroyed with incendiary grenades in August 1992, the National and University Library had housed over 1.5 million volumes, including rare books and manuscripts.26 Hence, the physical condition of what remained of the building – a hollowed-out structure in the continual process of disintegrating, deteriorating as it fell apart – affected both the work displayed and the conditions of its viewing. At the ‘Sarajevo Caryatids’ exhibition, the performative aspect of this ruin was literally enacted when leftover pieces of brick fell from the remaining dome structure, breaking the glass atop the photographs where they leant up against the damaged pillars in the library’s hexagonal central space.27

In addition to the performativity of the exhibition (as in the case of ‘Witnesses of Existence’ and, in a different way, that of ‘Sarajevo Caryatids’), one can also speak of the performative in the context of traditional media such as sculpture, which gained a new dimension during the siege of Sarajevo. In the month of August 1994, Alma Suljević prepared her monumental sculpture Centauromachy, made of steel, the remains of a burnt tram and its tram platform, for a ten-day journey around the city.28 Unfortunately, it was not possible for this work – symbolising the battle between civilisation and barbarism and commemorating the deaths of those who lost their lives on May 2 1992 in one of the biggest battles in the city, when this tram was set ablaze – to go on its journey as planned and so to challenge the imposed spatial conditions.29 It nonetheless represents the manifestation of an idea of the theatricality of a monumental sculptural project and its (potential) performative reclamation of public space.

In wartime, it becomes almost impossible to make a clear distinction between art in a public place, and art as a public space, that is, between a sculpture that is public only in terms of its size, scale and free access, and one that refers to its location and thus intervenes in the very social fabric of the city, both physically and socially.30 Enes Sivac’s Equilibrists (1994), a composition of wire sculptures of three human figures, one cycling, one flying and one jumping – was directed at wartime destruction both visually and metaphorically, including through the performative act in which it obtained its final appearance.31 Wrapped in paper, the sculptures were erected above the Miljacka River in the immediate vicinity of the burnt-out Central Post Office, of which only the shell remained. On the opening night of the exhibition in which they were presented, Sivac set the paper-wrapped Equilibrists on fire.32 In this performative inauguration one can recognise an iso-anthropomorphism of nature and architecture: the river symbolising impermanence and transience, the ruins evoking deterioration and bodily decay.

The Miljacka River itself became a surveillance zone during the war, its banks and bridges an arena for snipers from the surrounding hills. Sarajevans ran when crossing the river, taking swift steps which may have been what was alluded to by ‘Overtaking the Wind’, the title of Sivac’s exhibition. Also in 1994, Bojan Bahić and Sanda Hnjatuk, members of the Art Publishing group, protested the fact that, in the war, rivers had become ‘imposed walls’.33 In their action This is not a Wall!, citizens participated in the writing of banners on the Drvenija Bridge. These messages of peace were thrown into the river and launched downstream.34

These art practices, in which objects and bodies were placed in situations where the presence of the artists was a necessity for the materialisation of the work, involved not only contextual and spatiotemporal traits, but also the participation of the viewer. However, the spectatorship that unfolded in besieged Sarajevo’s open public spaces involved the body’s exposure to death, especially when taking into account that such gatherings were ‘forbidden’ – that is to say, targeted. Thus, the devastated buildings played a special role in the sense that they were analogous to open public spaces, making engagement in such spaces something radical – because it resisted the control mechanisms aimed at banning movement and gatherings.

As such, the subversive quality of these disruptions to the panoptic mechanism of power was also in their ability to generate relations that opposed strategies of surveillance and control. Attendance at these site-related or site-oriented exhibitions surpassed other cultural events since communication was grounded in multiple levels of discursive interaction between artist, site, and audience, and between members of the audience themselves. The exhibition openings initiated gatherings, communication and dialogue, producing zones of human relations. Visitors gathered around warm tea, exchanged information and engaged in discussions about ways of surviving in a besieged city. This communication between artists, cultural workers, exhibition visitors and casual passers-by who came to the openings unknowingly, produced alternative forms of socialising, social relations and community identifications. Through participation in these events, micro-communities were created, albeit they were never fixed and complete. Rather, they were always in the making, a process of creation, communication and the sharing of ‘the common human condition’, recalling Jean-Luc Nancy’s notion of community as occurring where ‘the common condition is at the same time the common reduction to a common denomination and the condition of being absolutely in common’.35

Nusret Pašić, Witnesses of Existence, 1993, Sutjeska Cinema, Sarajevo, 1993. Courtesy: Archive of the Obala Art Centre.

The experience of survival in the besieged city, reinforced by the physical condition of the ruined spaces that corresponded to the city’s annihilation, brought together diverse people in a process in which, through their interaction and communication, social space was produced. In these specific sociopolitical circumstances and spatial situations, artists and audiences became engaged in social processes in which the artist was not only the author of the work, but also an equal member of the community, using elements of socially engaged practices to make interventions in the social fabric. Such events were able to empower, regenerate and produce a social body that showed resistance and attempted to change and humanise the reality of war. This emancipatory potential was a significant and distinctive quality of the artistic and curatorial transformation of ruins into temporary exhibition spaces.

The Emancipatory Potential of Artistic Practices in Spaces of Destruction

The siege of Sarajevo initiated artistic actions and curatorial projects that resisted mechanisms of surveillance and control; through the performative appropriations and reclamation of public spaces as spaces for people, and the revitalisation of ruins as alternative art spaces. These practices also challenged the prevailing art forms in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as pristine gallery spaces and their conventional exhibition formats. Art limited to traditional media and absent of social and political context was replaced by subversive momentary actions, performances and performative spatial interventions that introduced alternative modes of creating, exhibiting and viewing art. Overturning the traditional relationship between artist, artwork and spectator, these emerging time-based and context-bound experimental, non-institutional, artist-initiated and independent-curatorial artistic practices evolved in resistance to the state of siege, and in response to the needs of the current conditions and circumstances.

Because in war, everything becomes temporary, momentary, subject to transformation and decay; from the urban social fabric to the human body, tortured, massacred, mutilated to the point of being unrecognisable. The reality of life changed to such an extent that it was almost impossible to maintain the autonomy of art. Due to the lack of everything, including materials, space to work and neutral, clean white gallery walls, artists challenged both conventional artistic means and the notion of the eternal and timeless nature of a work of art. It was inevitable that, during those years, art would move away from the sphere of aesthetic autonomy. In place of the isolated status of the work of art embodied in the ‘white cube’ gallery concept came the placement of the object or body in non-gallery spaces of destruction that directly indicated the physical, psychological and socio-political state of siege. Thus, with the use of nontraditional artistic means and materials resulting from destruction (debris, remnants, waste), interventions in devastated buildings initiated events and situations in which not only the temporal and spatial status of the work of art was transformed, but in which ruins were transformed into spaces of communication and socialisation, spaces of participatory practice and the creation of micro-communities that resisted mechanisms of surveillance and control.

It was the siege that brought art into life, in the spaces of these practices, making it more accessible and more meaningful. Artistic interventions in the damaged and destroyed buildings inevitably became site-related and contextually determined works, situations in which shared experiences and community identifications spontaneously occurred not directed by some curatorial or artistic agenda. In fact, in the exhibitions and artists’ actions discussed in this essay, there was no curatorial imperative – the artists were in direct control of the display format, and the organisations that assisted them with the technical and logistical aspects did not impose a curatorial agenda. The only exception to this was the curated exhibition ‘Witnesses of Existence’, whose later restaging in different places and outside of the besieged city proved, in any case, that it was its site- and context-specificity that provided the show with socio-political dimension.

The End of Subversive and Progressive Art Practices

After the war ended, the majority of the artists discussed in this essay returned to their areas of expertise, as well as to the practice of mostly showing their works in pristine gallery spaces. The Obala Art Centre, which had organised all the exhibitions in the ruined space of the former Sutjeska Cinema, had also founded the Sarajevo Film Festival in 1993 and, as this gradually evolved into the best festival in the region, the art centre consequently redirected its activities towards it. Its Obala Art Gallery, which had been actively working towards developing the independent art scene, stepped aside when the Soros Centre of Contemporary Art (SCCA) was founded in 1996, with a policy of ‘supporting those phenomena in contemporary art that transcend/expand existing media boundaries and frameworks’.36 Led by Dunja Blažević, the SCCA played a significant role in establishing a new art scene whose artists, mostly young and emerging ones, visibly departed from the dominant aesthetics of Modernism. The centre’s annual exhibitions, mostly organised in public spaces, represented a conscious curatorial intention to delve into the sphere of the socio-political. However, considering that the SCCA was part of the network of Centers of Contemporary Art established in former socialist countries by the Open Society Foundation and financed by wealthy American investor George Soros, one could say that this alternative art scene also served the foundation’s neoliberal social, political and economic agenda.

The infiltration of neoliberal capitalism into the sphere of culture marked a defeat of the radical potential of art; triggered during the siege, but dissolved in the processes of transition. The transition, viewed as ‘the ideological construct of dominance’37 whereby neoliberalism infiltrates the spheres of economics and politics, including cultural politics, has marked a new approach to power relations, characteristic of corporate neoliberal capitalism and the appearance of new information and communication technologies, which may be explained with Gilles Deleuze’s concept of the society of control.38 In the case of Sarajevo, if we were to attempt to connect Deleuze’s understanding of social control with Foucault’s theory of the panoptical disciplinary society, we would have to deal with the distinct specificities of the spatial establishment of control and power. Because, while in the war the body was subjected to the panoptic machinery of surveillance and punishment through spatial determination (siege), transitional capitalist domination over corporeality is exercised in abstract space, by means of new technologies, corporations and markets, where control is ‘continuous and without limit, while discipline was of long duration, infinite and discontinuous’.39

Exhibition opening in Sutjeska Cinema, Sarajevo, 1993. Courtesy: Archive of the Obala Art Centre.

Most of the artworks discussed in this paper were presented at the exhibition Realize! Resist! React! Performance and Politics in the 1990s in the Post-Yugoslav Context at the Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova (MG+MSUM), 24 June – 10 October 2021, curated by Bojana Piškur with guest curators Linda Gusia, Jasna Jakšić, Vida Knežević, Nita Luci, Asja Mandić, Biljana Tanurovska-Kjulavkovski, Ivana Vaseva, Rok Vevar and Jasmina Založnik. See also A. Mandić, ‘The Performative as Resistance to the Violence of War and Transition’, in Realize! Resist! React! Performance and Politics in the 1990s in the Post-Yugoslav Context (ed. Bojana Piškur), Ljubljana: Moderna galerija, 2021, pp. 99–123.

During the four-year siege, the Chamber Theatre (Kamerni teatar) alone organised over a thousand theatre performances, and in the very first months of the siege the Sarajevo War Theatre (SARTR) was founded. See Sarajevski memento: 1992–1995, Sarajevo: Minstarstvo kulture i sporta Kantona Sarajevo, 1997.

Claire Doherty uses ‘situation specificity’ to describe the ways in which contemporary artists respond to and produce place and locality. Claire Doherty, ‘Introduction/Situation’, Situation: Documents of Contemporary Art (ed. Claire Doherty), London and Cambridge, MA: Whitechapel Gallery and The MIT Press, 2009, p. 13.

Infrastructure such as transportation, sewerage and communication systems, as well as energy, power and water supplies. On ruin as ‘fragile equilibrium between persistence and decay’, see Brian Dillon, ‘Fragments from a History of Ruin’, Cabinet 20, Winter 2005–6, available at cabinetmagazine.org (last accessed on 10 May, 2022).

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of a Prison (trans. Alan Sheridan), New York: Vintage, 1995, pp. 195−228.

Grbavica is a residential area located on the west bank of the Miljacka River, in the heart of Sarajevo. During the siege it was occupied and isolated from the rest of the town, and it functioned as a sniper’s nest.

Henri Lefebvre, The Urban Revolution (trans. Robert Bononno), Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

On the functional inversion of the disciplines, see M. Foucault, Discipline and Punish, 210–11.

Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (trans. Steven Rendall), (Berkley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1988), p. 37.

Jurić’s textual intervention into one of the Xeroxed photographs of the action reads: ‘Creative process with presence of the eye of a spectator (killer/sniper), 15 May 1992.’ Ante Jurić, War Art Diary of Ante Jurić (1992–4), archive of the Art Gallery of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Jurić’s statement of this action consists of a Xeroxed copy of one of Čančar’s photographs, annotated with the text ‘Streets are our galleries’, and ‘Streets are our working spaces’, Jurić, War Art Diary of Ante Jurić.

Duhovnost i destrukcija (Spirituality and Destruction), exhibition flyer consisting of a folded sheet of paper with texts by Azra Begić, Sadudin Musabegović, statements by Ante Jurić and Zoran Bogdanović, and biographical data on all three artists, 1992.

Jurić, ‘Sarajevski manifest’ (Sarajevo Manifest), 2 May 1992, War Art Diary of Ante Jurić.

Jurić, ‘Pucanje u material’ (Shooting at Material), 17 November 1992, and ‘Sarajevski pucanj 1992’ (The Sarajevo Shot of 1992), 13 June 1993, War Art Diary of Ante Jurić.

This was Jurić’s first enactment of Sarajevo Shot. The second performance resounded at the opening of the ‘Witnesses of Existence exhibition’ in 1993; the third one took place the same year, in front of foreign journalists at the Holiday Inn Hotel; the fourth was performed at the City Gallery Collegium Artisticum in 1994.

On the identity of site-specific work, see Miwon Kwon, One Place after Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity, London and Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004, p. 11.

For more information on exhibitions in Sutjeska Cinema, see A. Mandić, ‘Exhibitions in Damaged and Destroyed Architectural Objects in Besieged Sarajevo: Spaces of Gathering and Socialization’, in Martino Stierli, Mechtild Widrich (ed.), Participation in Art and Architecture: Spaces of Interaction and Occupation, London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2016, pp. 107–26; and A. Mandić, ‘The Formation of a Culture of Critical Resistance in Sarajevo’, Third Text, vol. 25, no. 6, 2011, pp. 725–35.

James Meyer, ‘The Functional Site; or, The Transformation of Site Specificity’, Space, Site, Intervention: Situating Installation Art (ed. Erika Suderburg), Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000, p. 26.

Michael Fried, ‘Art and Objecthood’, in Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (ed.), Art in Theory 1900–1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, Oxford, UK & Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1999, pp. 822–34.

Tanja and Stjepan Roš, ‘Exhibition design “Witnesses of Existence”’, Svjedoci postojanja (Witnesses of Existence), (exh. cat., digital version), Sarajevo: Galerija Obala, 1993.

See Dubravko Brigić's film Svjedoci postojanja (Witnesses of Existence), TVBiH, June 1993.

András Riedlmayer, ‘Erasing the Past: The Destruction of Libraries and Archives in Bosnia-Herzegovina’, Middle East Studies Association Bulletin, vol. 29, no. 1, July 1995, p. 7.

Nermina Omerbegović, ‘Sarajevska kentauromahija’ (Sarajevo Centauromachy), Oslobođenje, 5 August 1994, p. 7; Angelina Šimić, ‘Kentauromahija se nastavlja’ (Centauromachy Continues), Oslobođenje, 14 August 1994, p. 7.

This sculptural composition was supposed to be dragged around the city’s tram route, including through the part of the city known during the war as ‘Sniper Alley’. However, for safety reasons, on the day when it was supposed to leave the tram depot, the artist postponed its journey until more peaceful times.

For the distinction between art in a public space and art as a public space, see Kwon, One Place after Another, pp. 56−65.

This sculptural composition was presented at the exhibition ‘Preticanje vjetra’ (Overtaking the Wind), 24 August 1994, at the summer festival ‘Beba univerzum’ (festival authors: Haris Pašović and Suada Kapić). See Muhamed Karamehmedović, ‘Kreacije pozitivne budućnosti’ (Creation of Positive Future), Oslobođenje, 31 August 1994, p. 7.

Testimony of Enes Sivac, in Suada Kapić, The Siege of Sarajevo 1992–1996, Sarajevo: FAMA, 2000, pp. 802–7.

National television (BHTV) coverage of the action, available at youtube.com (last accessed on 5 June 2022).

Jean-Luc Nancy, ‘La Comparution/The Compearance: from the Existence of “Communism” to the Community of “Existence”’ (trans. Tracy B. Strong), Political Theory, vol. 20, no. 3, August 1992, p. 371.

Dunja Blažević, interview with Dunja Blažević, Kultura i oblici, Sarajevo vol. 1, no. 2, 23 December 1997, p. 3.

Srećko Horvat and Igor Štiks, ‘Welcome to the Desert of Transition!: Post-Socialism, the European Union and a New Left in the Balkans’, Monthly Review, vol. 63, no. 10 (2012), p. 40.

Gilles Deleuze, ‘Postscript on the Societies of Control’, October, vol. 59, Winter 1992, pp. 3−7.