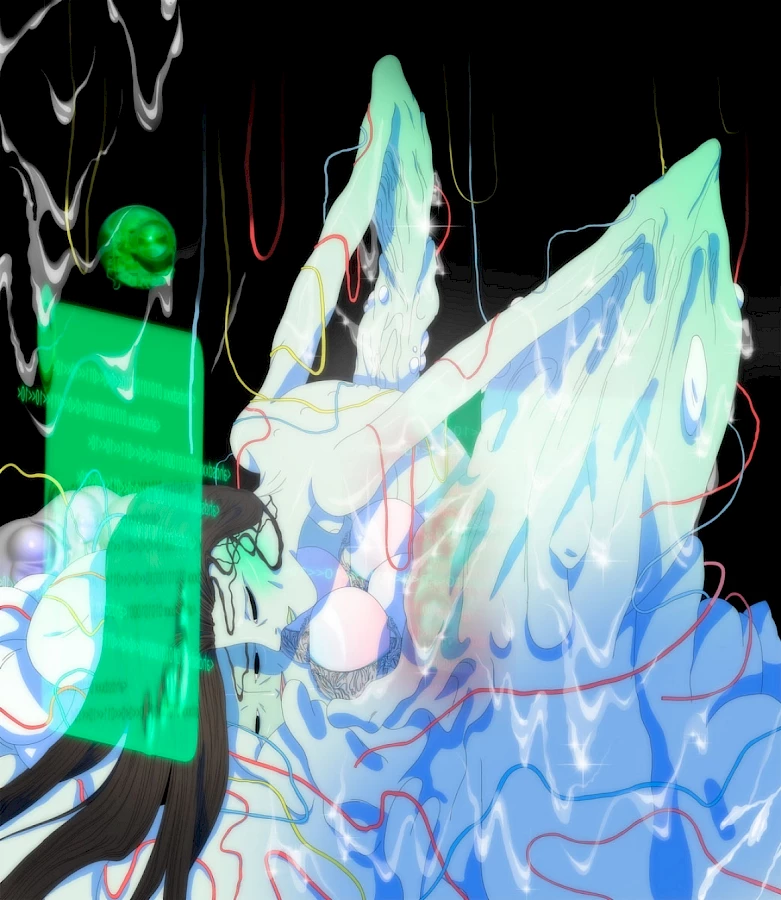

Andrés Tena, Precipitation, 2020. Ink drawing, digital colour and 3D forms.

The drone flew over the cemetery almost every night. She opened the windows of the room, letting the almost imperceptible hum fill her bones. The warm air mixed with the stench emanating from the piles of bodies, and the compost, that like a paste interwoven from all those infected organisms, carried a dense and bittersweet odour that plunged her into a light ecstasy, similar to that which she felt when she masturbated on sleepless days.

Since she had been working for various countries in different time zones to her own, a few weeks ago she had received a call that informed her that she had been selected to participate in a clinical trial with a recently synthesised and biblically named nanodrug. The treatment should already have started to take effect, but her insomnia and anxiety continued.

While she watches the drone retreat towards the new cemetery being built on the other side of the highway, she closes the windows and again enters the website that her friend had sent, in which the figures continue to rise, tallying the deaths in real time. A spasm runs up her spine and she switches off the screen. The room is tiny; barely a bed, a table, and a threadbare rug left by the previous tenant. Since the looting began nobody remained in the building. Only her. She had watched her neighbours ascend and descend the old staircase, vacating their houses, hiring trucks to help them move and start another life in any part of the country in which no more cemeteries were being built. She looked down at her hands, as if by focussing on the scratches across her palms she could recall something of what had happened the day it all began. Her mind is totally blank, a sticky white, like milk dripping hot between her fingers.

The hum of the drone passes again outside her window. She looks at it, as though the vehicle has eyes, and it stops for a few seconds directly in front of her face as if it was trying to tell her something. When the drone disappears she feels a piercing sound, like a goose screech, embedded in her eardrum. She fears she is beginning to hallucinate again and takes her raincoat, closes the window, and exits to the street.

This was her second trip to the clinic and this time the queue snaked around the entire building. They were all like her, women between 30 and 50 years old, with white skin and nervous tics. Mostly humanities graduates who had lost their jobs and ended up being recycled by the machine learning sector. Taggers, segmenters, annotators, they call them tukers or ghostworkers. She is agitated and can’t stop sweating. Although she knows that those who are going to treat her are not doctors, seeing herself in a clinic surrounded by men in white coats terrifies her. Every so often, a woman ahead of her turns to look at her sideways. You were there in the last looting of the north cemetery, she asks, barely moving her lips. At the door someone calls her name, and without responding to the woman, she walks hunched over towards the revolving door.

Inside the building the piped music calms her. There is something soporific about the lights and sounds in these corridors lined with waiting women. When her name is called again she gets up from the plastic chair with all her limbs numb. The consultation barely lasts five minutes. The man in the white coat doesn’t even look at her, and she lies, saying that she has been sleeping perfectly all week, that the treatment appears to be working. They tell her that even so, it is still recommended that they double the dose and that she would have to return to the clinic within two weeks. As she is rounding the corner to return home on public transport, suddenly she stops being able to see. The sensation is as though her iris is being pressed with alcohol-soaked gauze, as if her eyes were sweating acid. Before she can react, she has lost consciousness. Upon awakening, the woman from the clinic who had spoken to her while she awaited her turn holds her hand and strokes the wounds on her palm. They are neither in the street, nor her bedroom, nor in any place she has been before, but she recognises the stench of decomposing bodies. They must be close to a cemetery. Without understanding why, she breaks down in tears, feeling as though her whole body is melting. She becomes water, and floods the bed, the room, the hallway, while contemplating the face of the woman who scratches desperately at the walls, trying to reach the ceiling before drowning.

She cannot remember how she had managed to escape, or even if it had been real, but she still feels that gaze fixed in the well of her eye socket. She had had to close the eyelids of the drowned woman before the flood submerged her as well. It is that gaze that guides her now to that street, that building, that open door. As she crosses the landing she decides that she won’t return again to that clinic, the hallucinations are getting worse every time.

Inside everything appears normal, a family home. The furniture and bed are in their place, there is a chair in the middle of the room, the blinds are all drawn. She sits down and upon looking at her hands realises that the wounds on the palms have disappeared. Confusion dulls her chest. She doesn’t want to cry again for fear of what might happen. She clenches her jaw hard and bites down on her tongue, wanting to know if her body can still feel pain. She stains the floor with blood, and on bending down sees something hidden under the bed. There are four urns for ashes, the cheap kind, those from before. In the distance the howl of sirens can be heard rebounding across the walls of the room, and she feels she has to take the urns without knowing where to take them. Nor if she can manage all four alone, or if maybe it would be better to carry all the ashes in a single bag. The sirens feel closer and closer, hounding her. She hugs the urns to her chest and closes the door.

Back on the street, despite her hurry, she moves carefully to avoid spilling the ashes all over the pavement. She hears the buzz of a drone, feels it so close that she is at the point of giving up, running away and abandoning the remains of those strangers under a car. But she knows it’s impossible, that if she leaves the ashes they will want to catch her, that after the interrogation she will be taken to the hospital, that once inside she would be locked up until they do the tests, and that if she tested positive she would lose absolutely everything. And she knows that she would test positive. She would find herself again in a shabby room, without natural light, on stiff sheets that still smell like their previous corpse, pierced by the protesting wails of the multitudes that wait at the door of that place to ask for any kind of information about the health of their infected relative, or lover, or friend. The recollection of her previous admission intrudes on her thoughts as she runs faster, clutching the urns to her chest. Feeling that she can’t breathe, hot bile filling her throat. The hum of the drone is so close that the prickling between her legs becomes unbearable. She has to get to a cemetery, the only place she might be safe.

When they discovered that the cadavers of those who had died in the first wave of epidemics more than fifty years ago were emitting toxicity that infected the living, they decided to set fire to all cemeteries. That was how everything started. Professionals couldn’t explain why the contagion had returned so many years later, but the climactic factor seemed significant. The rising temperatures, coupled with the conditions in which the wave of biodegradable burials had developed, seemed like a concatenation of likely causes. The historians maintained that it was the paradigm shift with respect to death that took place during the early 21st century that imploded the benefits of an eco-sustainable funeral industry that wasn’t sufficiently developed. These companies grew so fast that numerous instances of negligence were committed in predicting the long-term polluting emissions that would be the result of this new type of cremation and burial. The technologies were not sufficiently developed, but the demand and the extremity of the situation was such that in many cases the regulations that already existed were contravened. The fires provoked a wave of popular revolts. Family members, friends, lovers, disobeying the sanitary hygiene measures, raided the cemeteries to be able to disinter their loved ones before the fire took with it all their remains. Many others also allowed themselves to be burned there, with their own, confining themselves in the churchyards while the flames laid waste to everything.

It was during those initial weeks that the contagions soared, paradoxically obliging them to build new necropolises as the old cemeteries were systematically demolished. In the chaos of looting, self-immolations, hospitalisations, funerals, and furtive mourning rituals, a website appeared on which many wrote their testimonies, uploaded videos, and offered recommendations so that their raids could be as organised and clandestine as possible.

From this more primitive community emerged what would soon become an organised network. Meanwhile, the death toll continued to rise. Then began the processes of territorial sectorisation and their consequent migrations. There were specific zones destined to house the new health and funeral infrastructure, while the majority of the population moved to safer enclaves, which in turn caused fierce confrontations. The network took advantage of this feeling of lack of control and began to organise themselves to occupy the vicinity of the graveyards and so guard the corpses inside.

The authorities deemed that everyone would end up being infected, and preferred to simply wait. They made the strategic decision to let die. They believed that by allowing them to be close to their buried loved ones they could better control the chain of infection. Now, the only important thing was that the drones made sure no one could move beyond the old cemeteries.

The internet was a dump. She could spend hours tracking down and accumulating sediments of old information, which, although it had nothing to do with what was happening now, made her feel more alive. Digital diagenesis. She was the only one of her family who survived, and for her time had stopped there, in that year. That’s why it took weeks for her to find out what was happening. It was through that website: someone had left her a message, they were searching for her. She had gotten so thin that her bones ached from spending so many hours glued to the chair, pounded by guilt. At first it was unbelievable, until, like everyone, she had to get used to the particles of ash that veiled the sky and irritated the nostrils. Now it was always night. She didn’t respond to the first message, nor the second, nor the third. She had thought herself safe because nobody knew that the urns were in the house, in the old sideboard in the living room, displayed where her sisters’ sports trophies had been. The urns were of imitation silver plastic decorated with flowers and fruit, with handles similar to porcelain teacups. In the beginning she had occasionally opened them by inserting the tip of her nose, as if breathing on the ashes with the heat of her body could make them resuscitate. With time, the urns only reminded her of the months that had passed until she could reclaim her dead. They had travelled kilometres to be cremated in another district because by then the city’s crematoria had already collapsed. They did not let her travel, and that wait devoured her inside.

The fourth message arrived just as she was hiding the urns under her bed. She had begun to have recurring nightmares in which the police would knock on the door, destroying everything until they found the urns to confiscate them, leaving her alone again, without her dead and without her ashes. This time the message is very different, saying simply: IT WAS NOT YOUR FAULT, THEY KNOW IT, GET UP AND GO. It is at that precise moment, with her body glued to the urns and the dust accumulated for months under the mattress, that the image of the night in which her mother said she had been infected flashes into her mind. This is a memory buried so deep in her skin that at first the details are blurred, until its clarity falls heavy on her chest, searing her internal organs. They had all been waiting in that room, the television was on as usual and broadcasting the live news. They could hear the sizzle of oil frying in the kitchen next door, and her father had just walked in the door. They decided that it was better for the others to go to the house in the village, but she insisted that the roads were already closed and that they would never arrive. When her mother opened her mouth that night, she already knew how it would end. She felt that she had known it long ago, as though her entire life had meaning only to squeeze it out in that precise moment. But she didn’t imagine she would never get to say goodbye.

When she arrived, everything seemed calm. The situation was no longer exceptional, and those who surrounded the old cemeteries had started to make life there, between the niches, as if it were a town square. Accustomed to the stench, to the blackness of the sky, to the churned and muddy sands, the landscape seemed to echo some mediaeval scene. Every day they received fresh flowers, and some women braided them into ornaments that they hung from the roofs of the pantheons of the wealthiest deceased. These tombs, that were already unoccupied, now functioned as storage where they accumulated what was necessary to support the future enclosures. This was the oldest cemetery in the city. She, believing that she was just visiting, arrived with nothing, but when the women recognised the prophecy in her face they began to kick hard against the earth. They gave her a wooden shovel and with their gaze invited her to dig, as was tradition, her own grave. She would have to spend her first night there, buried alive, surrounded by the skeletons of ancient corpses, the bacteria and creatures that reproduce in the deepest strata. She is so thin that she can’t even hold the shovel, much less make a hollow in the earth, but nobody can help her. It will take hours. She rests from time to time, gazing hypnotised at that hole that is the reverse of her own body. The physical effort immerses her in a trance that takes her far, far away: she stops hearing the murmurs of those who flock around her, curious and impatient, she stops feeling the cold at the tips of her fingers and the soles of her feet supporting her weight. All her limbs are numb. Barely anybody is left awake when she finishes. She brushes off the mud that has clung to her clothes, washes her hands and face, and hums to herself as she introduces first one leg, then the other, and then the torso, until the nape of her neck senses the damp earth. There, looking up at the sky deformed by ashes, she feels suspended, in a kind of sway, as if her guilt had finally been interrupted. The few remaining who keep vigil start to toss fistfuls of earth onto her chest, her knees, her face. The grains of sand feel like little lashes on her skin, until she is completely covered. Hearing their footsteps receding, she squeezes her eyes shut tight and opens her mouth. Into the seam of her lips slip pebbles and bits of clay. She wants to gag, eating all that earth. Down below she has developed an all-consuming hunger.

She has spent more than two days interred. Although she can hear movement above and voices calling her, she remains unmoved. As if she were really dead. Before, on other occasions, she had recreated this situation, imagining her death from the outside, holding on to the relief that lightened the weight of her body when the blood stopped pumping. Caressing herself while the last exhalation emptied her insides of guilt, extricating that guilt that had ended up being the only thing that filled and crushed everything. She has her eyes closed and mouth full of sand when she feels fingers breaking through the soil until they collide with her eyelids. Those fingers belong to hands that forcefully disturb the earth covering her thin body, and to arms that pull at her hips, pulling her out so roughly and softly. The fingers open her mouth and mingle with the saliva and mud on the surface of her tongue. A second body joins the effort, managing to make her abandon that hole that is her resting place. She resists with impassiveness, letting gravity crush her again against the soil, closing her eyes tighter each time. She perceives the shadows of various bodies surrounding her curiously, whispering, as if cooing to her. She doesn’t understand what they want from her, or why there is so much anticipation. You are an omen, they say, the mourner, your grieving has consummated the epidemic. She doesn’t want to listen to them, she doesn’t want to have anything to do with all these people who worship her as if she were a miracle, but they won’t leave her be. She is not a miracle. Miracles do not exist. She just wants to take her urns of fake silver and bury herself. Go home and lie under the bed, embrace them, and disappear. A drone flies over the cemetery.

She begins to hear screams, as if the screeching of a flock of geese has embedded itself in her eardrums. She feels an enormous heat coming down from the sky, jets of fire devouring the branches of the trees, the braided flowers, the statues of virgins and angels. Fire hoses now filled with kerosene explode over the cemetery like fireworks. Everyone around her is running, yet she cannot move. She only feels the orange, so intense that it locks her feet to that exact spot, right next to her tomb. The human stampede slams against the walls of the enclosure. They have been locked inside, in that bonfire that forces them to climb the cypresses and run in concentric circles, in a desperate and useless choreography against death. And she, in her remaining time, understands what is happening, that this is the last of the cemeteries with infected corpses. Amid the screams she sees a woman with her hair in flames approaching. She runs, and as she staggers her burning hair traces a sparkling trail. She carries four urns decorated with fruit and flowers in her arms, and shakes her head insistently so that the fire cannot reach the ashes. They are about to touch, she can almost grasp the urns with her fingers when she feels that her legs too are on fire, and that the woman with the burning hair is melting in front of her. Flesh disintegrates faster than plastic, but before it burns, she watches as the ashes fall and spill onto the earth.

Translation from Spanish: Madeleine Stack

The views and opinions published here mirror the principles of academic freedom and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of the L'Internationale confederation and its members.