Solidarity in Arts and Culture. Some cases from the Non-Aligned Movement

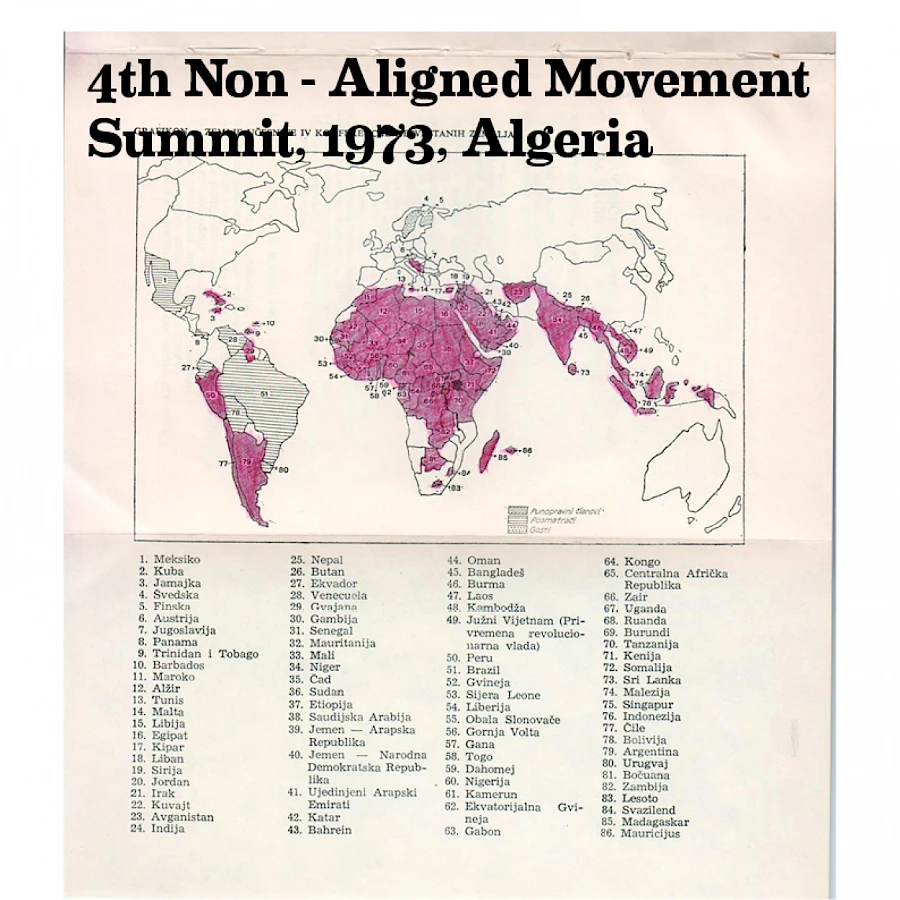

The map published in the book: Ranko Petković, Teorijski pojmovi nesvrstanosti, Rad, Belgrade, 1974.

The Non-Aligned Movement1 (NAM) functioned as a social movement in the international system, a third way between the two blocs, aiming to change the existing global structures and to create a more just, equal and peaceful world order. It was, in its essence, an anti-imperialist, anticolonial and antiracist movement (Singham & Hune 1986, p. 1).

The NAM thus represented the first major disruption in the Cold World map. While the 1961 Belgrade Summit was mostly an Afro-Asian and Yugoslav project, the movement acquired worldwide dimensions with the inclusion of Latin America2 a few years later. The fate of this constellation of energies is probably one of the least understood phenomena of our times, but it is certain that its disappearance from the world's political stage is directly linked to the rise and victory of neoliberalism, especially after 1989.

Great importance was given to art and culture in cultural politics influenced by the NAM and specific types of socialism. I will focus on transnational solidarity projects such as the Museo de la Solidaridad in Santiago, Chile, the Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Art and the Week of Latin America in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, and argue that this was solidarity as a national project. Political solidarity within the NAM, economic solidarity between the "Third World" (which was stimulated by the New International Economic Order in the 1970s), and cultural solidarity3 were not only in line with the official approach and pragmatic goals set by the non-aligned governments, they were an expression of a much wider historical and political moment of peoples' struggle for decolonisation and liberation in the world.

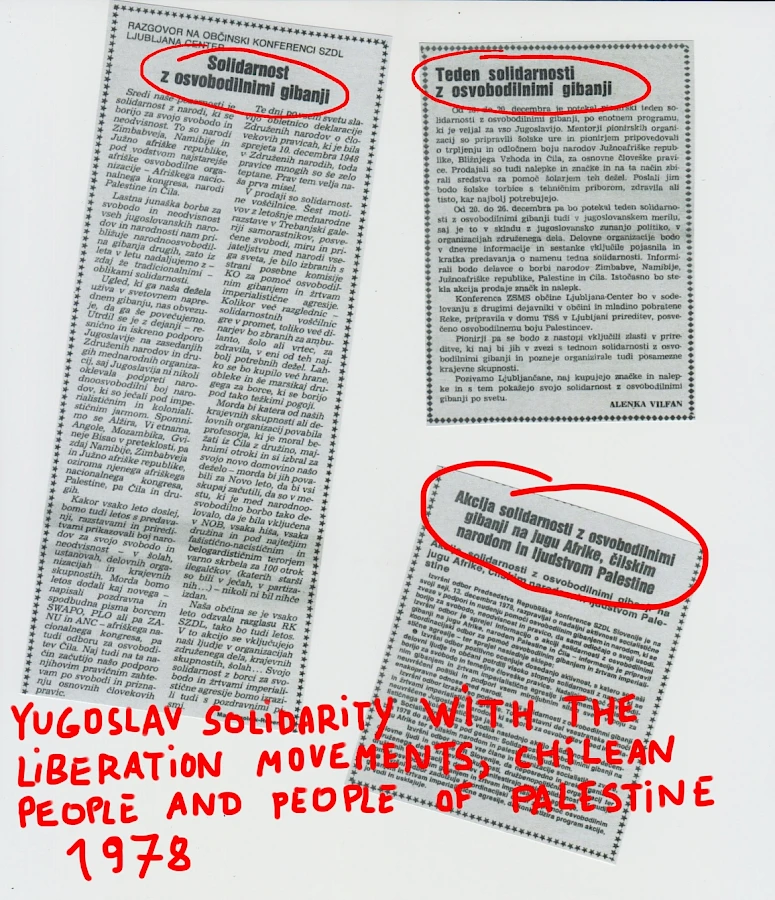

Various newspaper clips from Slovenian press, 1978, Archives of Moderna galerija, Ljubljana.

Fifty years ago, Yugoslavia was still a relatively prosperous socialist, non-aligned country with a fairly well-developed economy, following principles of self-management. In 1970, Salvador Allende, the Unidad Popular party candidate, was sworn in as the first elected Marxist president of Chile. The Chilean Path to Socialism – socialismo chileno – was widely admired in some parts of the world. At the Non-Aligned Summit in Algeria in 1973, Chile became a full time member (for less than a year).

Words like solidarity, fraternity, equality, peace, and fight against imperialism, colonialism, and apartheid resonated at the NAM summits, at UNESCO seminars on culture, at political rallies around the world, in museums... It also seemed as though art and politics were united in their quest to create utopian models adapted to social and political changes. It is no coincidence that experimental museology and concepts such as the integrated museum, the social museum, the living museum, and the museum of the workers were widely discussed in the so-called Global South.

There seemed to be a specific "socialist inspired internationalism". In 1956, at the UNESCO conference in New Delhi, shortly after the 1955 Bandung conference, representatives of the Third World (or "the South", south as a critical geopolitical entity) dedicated themselves to promoting alternative routes of cultural exchange (Gardner & Green 2013), different from those in the First and Second Worlds. A wave of new biennials sprung up in NAM countries like in Alexandria, Medellin, Havana, Ljubljana, Baghdad, for instance. Amilcar Cabral, anti-colonial thinker and political leader from Guinea-Bissau wrote: "people are only able to create and develop the liberation movement because they keep their culture alive despite the continual and organized repression of their cultural life and because they continue to resist by means of culture, even when their political and military resistance is destroyed" (Cabral 1983, p. 6). The 1970 Lusaka NAM resolution in Zambia stated: "World solidarity is not only a just appeal, but an overriding necessity; it is intolerable today for some to enjoy an untroubled and comfortable existence at the expense of the poverty and misfortune of others".4 In 1972, a UNESCO seminar was organised in Santiago, at which museum workers discussed a new type of a social or integrated museum that would link cultural rehabilitation with political emancipation. It would be socially progressive without being ideologically restricted by any political representation. At the 6th Conference of the Non-Aligned Countries in Havana, Cuba, in 1979, Josip Broz Tito, president of Yugoslavia, spoke of the "resolute struggle for decolonisation in the field of culture".5 The emphasis was on questioning intellectual colonialism and cultural dependency. The idea was not only to study the Third World, but to make the Third World a place from which to speak. "Location" ("a horizon beyond modernity, a perspective of one's own cultural experiences" according to Enrique Dussel) was the philosophical theme addressed in 1974 when the "South-South Dialogue" between thinkers from Africa, Asia, and Latin America was initiated. The first meeting was held in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania.

One common issue shared by the NAM states was the question of cultural imperialism. Secondly, there was a need to create different modernities; the so-called "epistemologies of the south" (de Sousa Santos 2016), as an understanding of the world that was larger than the Western understanding of the world. The NAM had made cultural equality one of their most important principles very early on, at the Cairo conference in Egypt in 1964. This meant, on the one hand, that a number of African and Asian countries sought to regain works of art which had been taken out of their countries during colonial times and put in various museums in New York, London, and Paris, and on the other hand, that people who had been denied their culture in the past started to realise the emancipatory role it played in their lives. The cultural development of decolonising countries became as important as their economic development. Importantly, this culture was no longer meant only for the elites; art and culture were to be accessible to all. We could even say this was a kind of epistemological solidarity.

A new world information and communications system was formed, so called The Non-Aligned News Agencies Pool,6 which worked as an international, collaborative cooperation between Third World news agencies whose main objective was to decolonise the news, provide its own mass media channels and to offer counter-hegemonic reports on world news concerning the developing nations.

THE CASES

The concept of non-alignment became the main component of Yugoslavia's foreign policy as early as the late 1950s. Socialist revolutions had a lot in common with anti-colonial and anti-imperialist revolutions, which made the Yugoslav emancipation in the context of socialism particularly significant. As Singham and Hume put it: "It was Tito who revealed to the Afro-Asian world the existence of a non-colonial Europe which would be sympathetic to their aspirations. By bringing Europe into the grouping, Yugoslavia helped to create an international movement" (Singham & Hune 1986, p. 52). President Tito traveled to various African and Asian countries on so-called "Journeys of Peace" (for example his famous visit to Western African countries on the Galeb (Seagull) ship in 1961) to support their independence and to express solidarity with the newly independent countries. These "solidarity" travels subsequently acquired a strong economic (and cultural) dimension and resulted in new spheres of interest and exchange amongst NAM countries (architecture, student exchange programmes, trade fairs, industrial design, art exhibitions).

In 1984, The Josip Broz Tito Gallery for the Art of the Non-Aligned Countries was inaugurated in then Titograd, Yugoslavia, with the aim to collect, preserve and present the arts and cultures of the non-aligned and developing countries. The document was adopted at the 8th summit in Harare, Zimbabwe, and soon after the gallery became a common institution for all the NAM countries. Unfortunately, their goal to create a Triennial of art from the NAM countries never happened because of the war in Yugoslavia. Nevertheless, the collection still exists today and includes over 1000 works, mostly donations from all over the world.

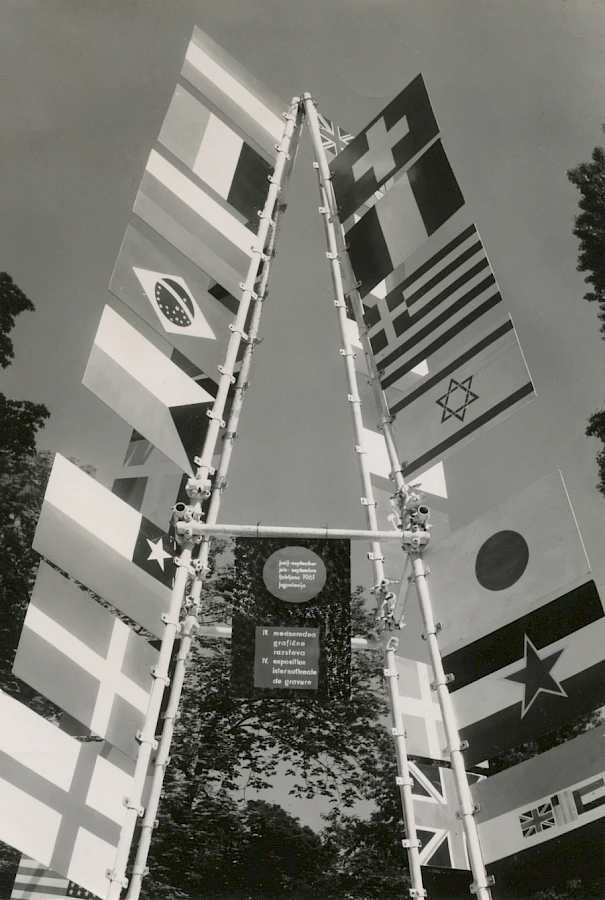

Exterior installation, 4th International Exhibition of Graphic Arts, 1961, Moderna galerija, Ljubljana. Photo courtesy: Moderna galerija, Ljubljana.

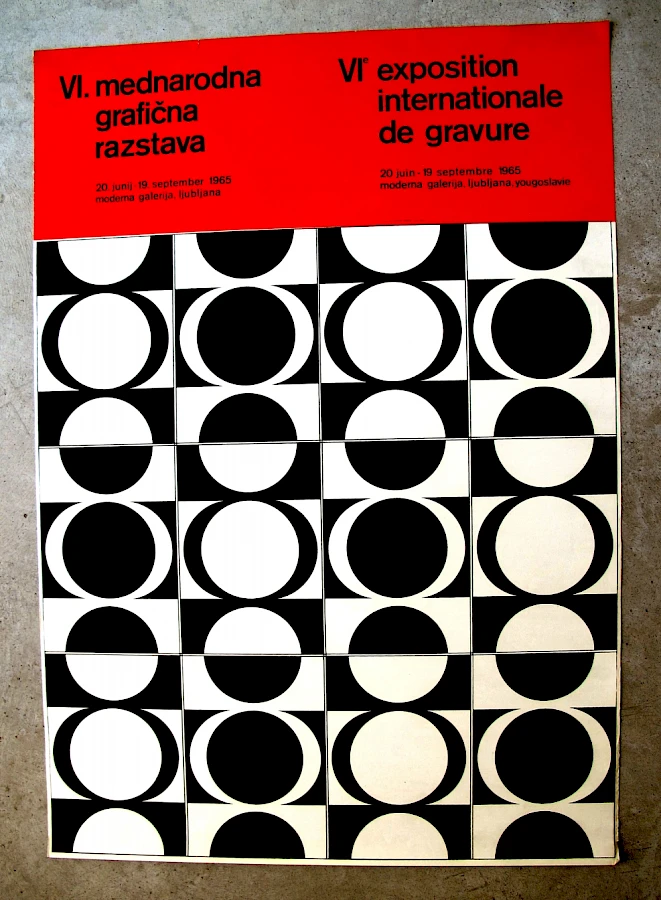

The Ljubljana (International) Biennial of Graphic Arts started in 1955 at the Moderna galerija. This biennial was specifically linked to the non-aligned cultural politics. It was founded by a long-time director of the museum, Zoran Kržišnik who saw this as a possibility "for a projection of values such as the presence of freedom, modernity, democracy, openness and so on in society" (Grafenauer 2013). In an interview, he pointed out that he had shown President Tito that the Biennial of Graphic Arts was actually a materialisation of what was being referred to as openness, then seen as non-alignment. The approach for acquiring works for the exhibitions was twofold: on one hand, the biennial jury made their own selections in order to get the best representatives of, for example, the Ecole de Paris, and on the other, some countries were offered direct discretionary invitations so they could present whatever they wanted without interference.

Installation view with the international jury, 5th International Exhibition of Graphic Arts, Moderna galerija, Ljubljana, 1965. Photo courtesy: Moderna galerija, Ljubljana.

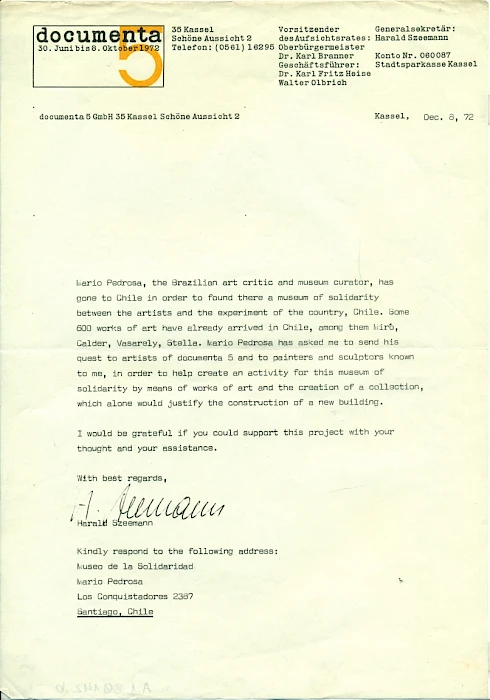

Consequently, the biennial exhibited "basically everything, the whole world" especially after the first NAM Conference in 1961. The jury included representatives of museums such as the Guggenheim, the Tate Gallery, Moderna Museet in Stockholm, the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo, as well as the curator critics Pierre Restany, Harald Szeemann, William Lieberman and others.

Ivan Picelj, poster for the 6th International Exhibition of Graphic Arts, 1965, Archives of Moderna galerija, Ljubljana.

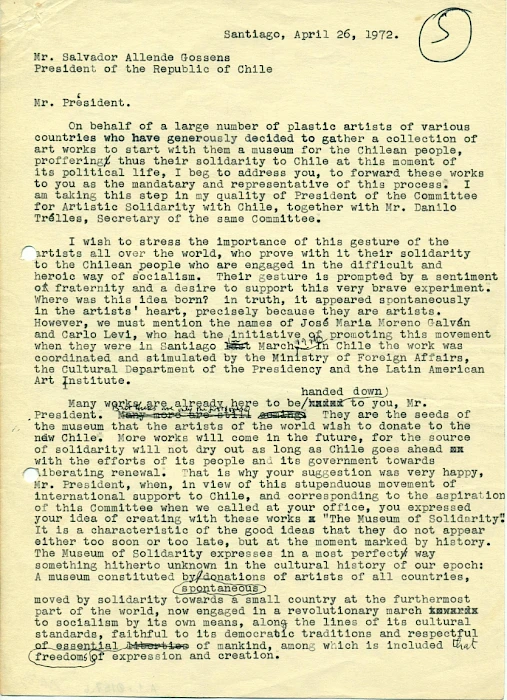

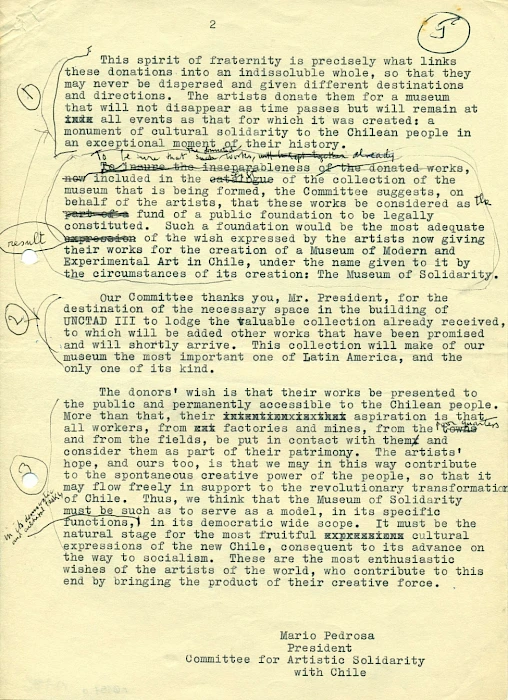

In Chile, the Museo de la Solidaridad was born in 1971 out of the visionary idea of a handful of individuals later named the International Committee of Artistic Solidarity with Chile, with Mario Pedrosa, a Brazilian art critic in exile there, serving as its president.

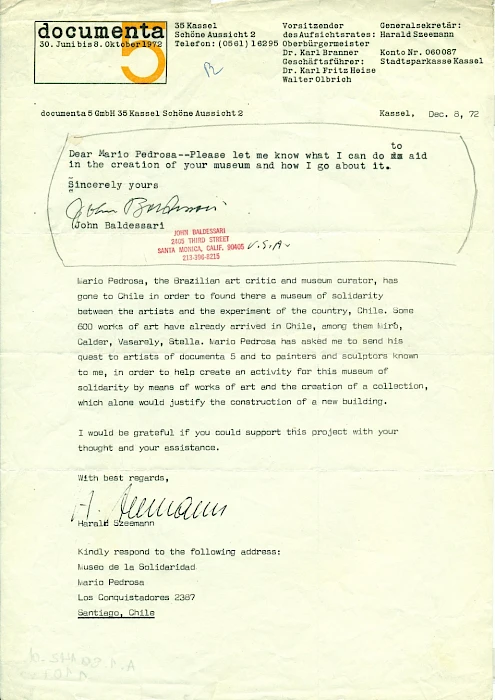

Among the committee members were Dore Ashton, an art critic from the United States, Pablo Neruda, poet and ambassador of Chile in Paris, Edward de Wilde, director of the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, Giulio Carlo Aragan, Luis Aragon, and Harald Szeemann. The founding idea was articulated in April during "Operation Truth", when President Allende invited international artists and journalists to "understand the process that his nation was living". He sent an appeal to artists to support the new path Chile was taking by donating works of art. Donations from all over the world started to arrive, 600 works in the first year of the museum's existence alone, in a heterogeneous mixture of styles: Latin American social realism, Abstract Expressionism, Geometric style, Art Informel, experimental proposals, and conceptualist works. Harald Szeemann, who was at the time directing documenta 5, sent a letter to all the participating artists asking them to donate works of art to the new museum in Chile.

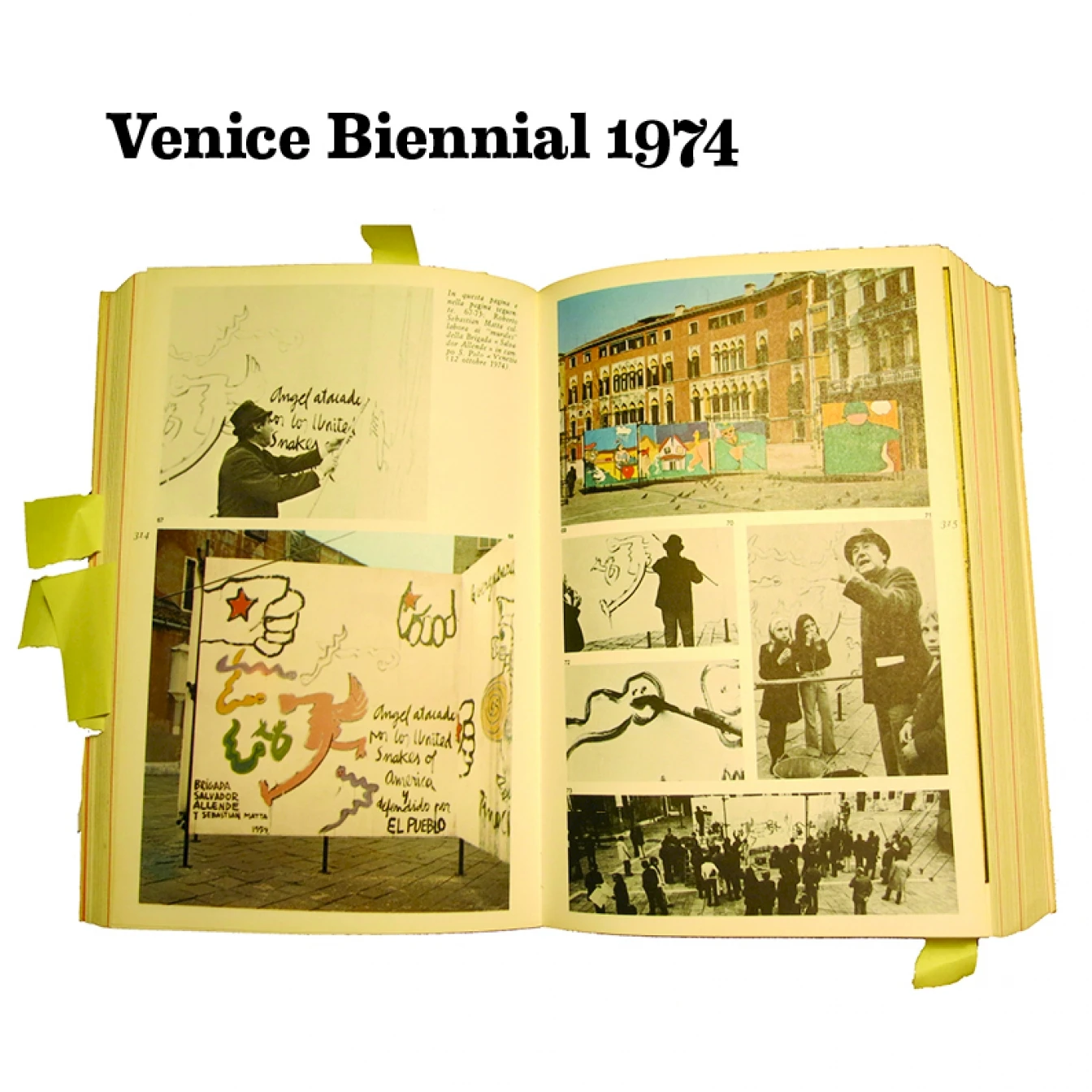

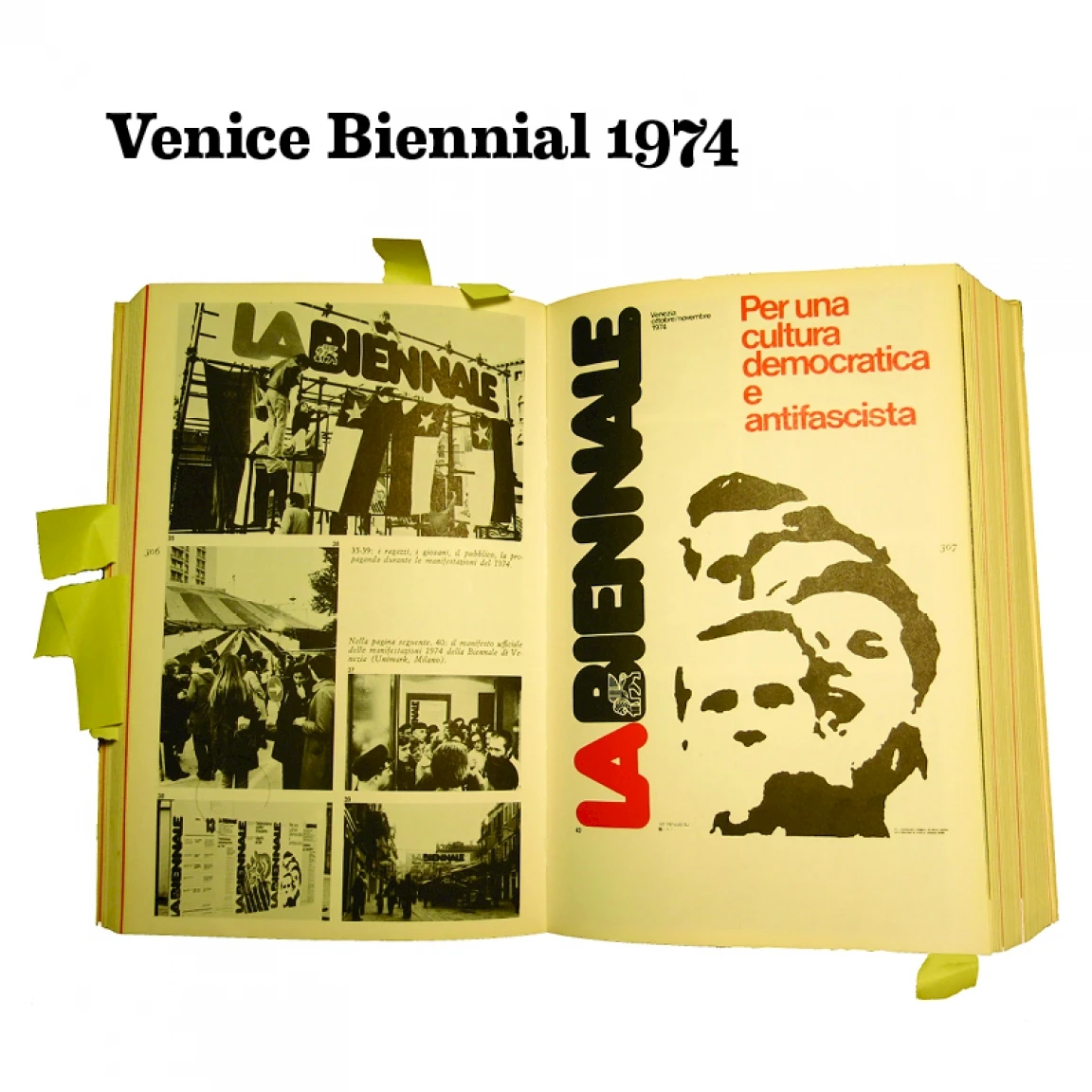

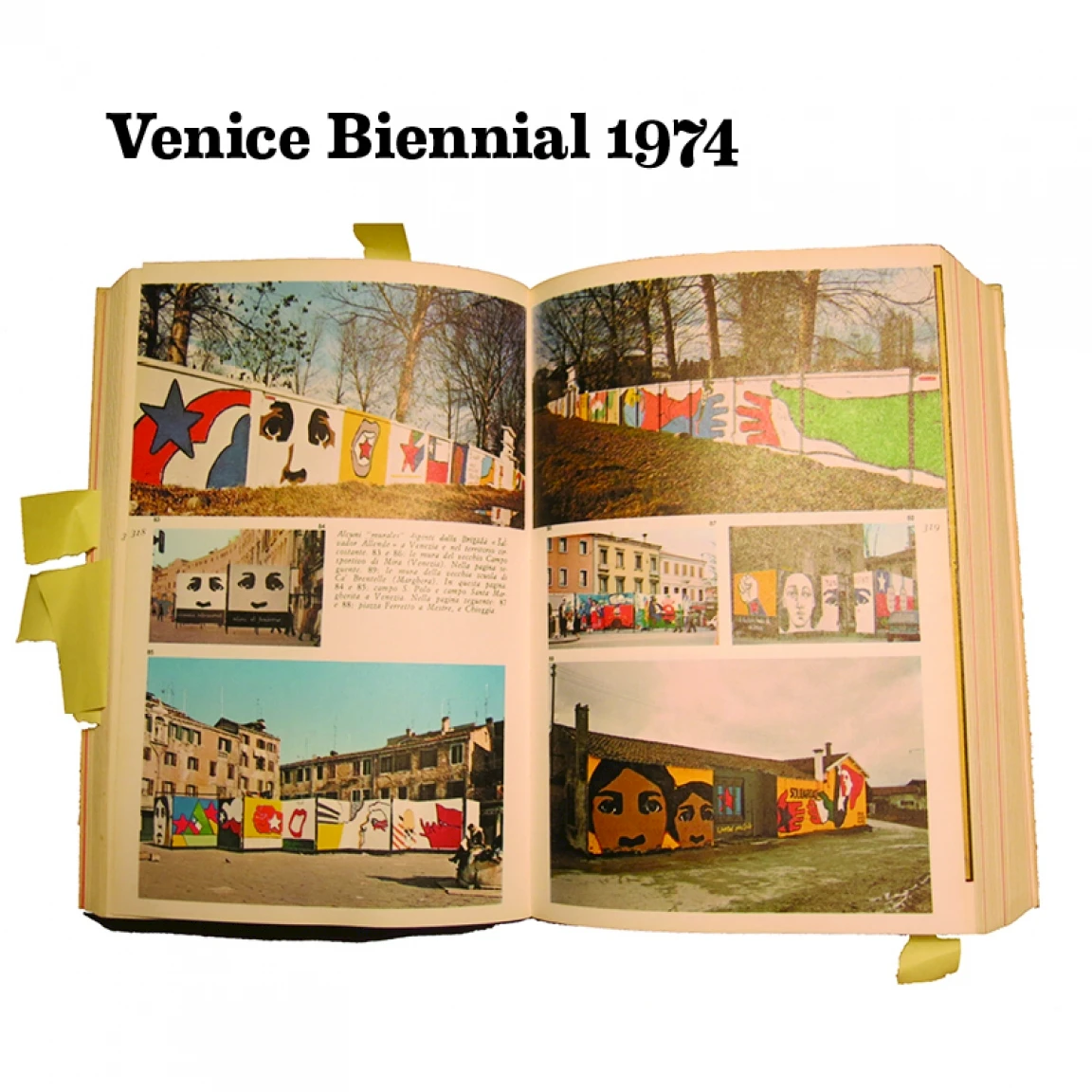

La Biennale di Venezia, Annuario 1975 / Eventi del 1974.

La Biennale di Venezia, Annuario 1975 / Eventi del 1974.

La Biennale di Venezia, Annuario 1975 / Eventi del 1974.

The act of donation was a political act in itself. It was also a museological experiment; "a network of people from the world of culture who contributed works, ideas and connections toward the shaping of a museum that was not hierarchical, but transversal and polyphonic" (García Pérez de Arce 2014, p. 45).

Justo Pasto Mellado summarised the situation thus: "While in other parts of the world, some works by the avant-garde bring into question the legitimacy of museums, in those places where the history of museums is incomplete, the desire for one becomes an absolute imperative" (Mellado 2008).

This museum was in tune with cultural democratisation underpinning the party politics: to bring art out of the museums and into non-specialised spaces. This was done through approaches such as the "Tren popular de la cultura", the "casas de la cultura", traveling shows in tents, protest posters, murals (Brigada Ramona Parra), etc. Pedrosa spoke about the connection between art and workers, especially Chilean copper miners. President Allende seemed to understand the new mission of museums when he exclaimed at the museum inauguration in 1972: "This is not just a museum anymore. This is a museum of the workers!"7

This museum experiment ended abruptly in 1973 with Pinochet's coup d'état. Throughout the dictatorship, the art collection remained in the basement of the Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of Chile, which was in the hands of the military. Dore Ashton was declared persona non grata and Pedrosa had to go to another exile, to Mexico. Some works were lost, and some destroyed.

Letter from Mário Pedrosa to President Salvador Allende. April 26, 1972. Solidaridad (Fonds), Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende Historical Archives, Santiago.

Subsequently, the world reacted. The 1974 edition of the Venice Biennale was atypical: with a "clear and distinct antifascist choice of direction" (Archivio, p. 72). The Permanent Working Group of the Biennale dedicated a series of artistic activities to the freedom of, and solidarity with, Chile. These took place all over Venice, in the industrial suburbs, parks, factories, garages, sports grounds... and involved films, music, performances, an exhibition of posters (in the Giardini and in the Italian pavilion), discussions, and sixty-two murals painted by the Salvador Allende International Brigade.

Circular note from Harald Szeemann inviting artists from documenta 5 to donate to the Museo de la Solidaridad. December 8, 1972. Solidaridad (Fonds), Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende Historical Archives, Santiago.

Along similar lines was the Week of Latin America (Vesić c. 2012/2014) in 1977, in the Belgrade Student Cultural Center, which consisted of a series of art events dedicated to burning political issues (debate about military regimes and the politics of non-alignment in Latin America) with an emphasis on art practices that "closely connect artistic and revolutionary acts". The Salvador Allende Brigade painted a mural entitled Solidarity.

This should not be considered as some kind of exoticism of the past, nor should it harbor nostalgia of the movement itself, as we know that many NAM states were quite far from the principles the movement promoted. From today's perspective, the concepts of nation-states, identity politics, and exclusive national cultures, which appeared in cultural political agendas at the time, can be seen as highly problematic. The concept of solidarity also needs to be treated with caution: with whom are we solidary and how are we solidary? How can we avoid the "white savior complex" (Spivak 1988)? And what should be done with the fact that Syria, Pakistan, Libya and most African states are still members of the NAM?

Nevertheless, the movement should not be forgotten in so far as it envisioned forms of humanism that took as a starting point the life of peoples and societies that had been forcibly placed on the margins of the global economic, political and cultural system. The struggle against poverty, inequality, and colonialism in the world system coupled with trans-national solidarity could be useful in a reconsideration of the history and legacies of the NAM today, at a time when colonialism has become more than evident once again.

In culture we are already doing that at some level by being involved in various networks, alliances, museum federations, knowledge production platforms, etc. These do not consist only of cultural operators, but join forces with social movements, grass-roots organisations and many others. They take into consideration the question of how relevant these ideas are to the development of international solidarity in the sphere of culture, transversally linking it with politics. Simultaneously new models of being together in the world, are envisioned, models that would enable us to live and not merely to survive, to paraphrase Svetlana Alexievich (2016, p. 30).

References

Alexievich, S. 2016, Second Hand Time, Fitzcarraldo Editions, London.

Archivio storico delle arti contemporanee, 1975, La Biennale di Venezia, Annuario 1975 / Eventi del 1974, Stamperia di Venezia, Venice.

Cabral, A. 1983, Return to the Source: Selected Speeches by Amilcar Cabral, Monthly Review Press, New York.

de Sousa Santos, B., 2016, Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide, Routledge.

García Pérez de Arce, I. 2014, "Museo de Solidaridad /Museum of Solidarity Santiago, Chile, The Polyphonic Museum of Salvador Allende", in Politicization of Friendship, Moderna galerija, Ljubljana.

Gardner, A.; Green, C. 2013, "Biennials of the South on the Edges of the Global", Third Text, vol. 27, no. 4.

Grafenauer, P. 2013, in The Biennial of Graphic Arts - Serving You Since 1955, on the occasion of the 30th Biennial of Graphic Arts Ljubljana.

Jakovina, T. 2011, Treća strana Hladnog rata, Fraktura, Zagreb.

Mellado, J.P. 2008, "Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende: the History of a Collection", in exhibition catalogue Lo Spazio dell'uomo, Fondazione Merz, Turin, viewed 7 March 2025.

Petković, R. 1974, Teorijski pojmovi nesvrstanosti, Rad, Belgrade.

Singham, A.W.; Hune S, 1986, Non- Alignment in an Age of Alignments, The College Press, Zimbabwe.

Spivak, G. 1988, "Can the Subaltern Speak?", in C. Nelson and L. Grossberg (eds.), Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, University of Illinois Press.

Vesić, J. c. 2012/2014, "The Week of Latin America: Murals by Salvador Allende (Ramona Parra) Brigades – 'Non-Aligned' Street Art", part of Parallel Chronologies. An Archive of East European Exhibitions, viewed 26 September 2016.