Tear Down the Statues of Columbus

Detail of the statue of Christopher Columbus in Barcelona, Laslo Varga

We should be infected with the rage of the anti-colonial and anti-racist movements and dismantle the symbolic platforms that underpin our Euro-white superiority.

‘By the way, sir, even if a statue of gold was made of Columbus, don’t think that the ancients paid him like this in his own time.’ Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, La natural historia de las Indias (‘The Natural History of the Indies’)

– Toledo, 1526, fol. xx

The recent anger around the statues and monuments that perpetuate the memory of colonial history may seem out of time and out of place; unbecoming of ‘advanced societies’. They are relics of the past, we are told, lacking in mnemonic scope or ideological content and their cultural and artistic value must be respected and protected as part of our heritage. Focusing on their supposedly vulnerable and innocuous appearance is one of the most effective ways of naturalizing the status quo across our modern regimes. From their pedestals, the old statues subtly and silently affirm the legitimate repositories of memory, even though their content has been long forgotten. The monuments confirm, seemingly without apparent violence, the order of privileges and exclusions transmitted over time. This angry revisionist fury is annoying and undignified because it transgresses the limits of that sacred, anachronistic and aesthetic sphere, where we place the founding myths of our system in such a way that they remain unquestioned and protected. It is for the same reason that the ‘tribal’ rites ostentatiously reactivated by the new right also cause much perplexity and anger – as they were also believed to be out-dated and should better be modestly removed from public view. Periods of intense crisis such as the one we are living through have the virtue of pulling the veils back and dispelling mirages. The power of attraction and repulsion is restored to apparently dormant symbols, which become like time-capsules condensing the meaning of historical processes that were as fierce in nature as they have been long-lasting in consequence.

Réplica, Daniela Ortiz, 2014. Video courtesy of the artist.

The case of the Christopher Columbus statues, a frequent object of both current celebrations of and protests against monuments in general, is an exemplary illustration of the way in which these landmarks operate in public space. Columbus stands seemingly indifferent, from the top of a central Madrid roundabout, witnessing ‘by default’ the military parades that mark the National Holiday every October 12, relieving institutional speech makers of having to make any direct mention of his person or meaning. The huge flag that has flapped at the statue’s side for a few years now, rivals the monument in height, filling the square with general symbolic meaning and making any precise reference unnecessary. What is explicit is that the leaders and the conservative parties have chosen this site to stage their performances of unity and their defence of the homeland, as have the far right, whose increasingly frequent demonstrations gather under the cry ‘Spain is broken’. These expressions of the neo-fascist tendency to invoke the ghosts of supposedly ‘glorious’ moments of the past, manage, despite their emptiness and imposture, to make visible the historical reasons that link profoundly the colonial world with the social and political order of the present.

Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit Madrid, Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez Peña, 1992. Photo courtesy of the artist.

The Peruvian artist, Daniela Ortiz, demonstrated this when she performed, among the Spanish crowd gathered before the Barcelona statue on October 12, 2014, the position of the kneeling and submissive Indigenous figure that appears sculpted next to the Catalan religious figure Bernat Boïl, who was a companion to Columbus on his second trip. Her performance made the cheerful flag bearers uncomfortable by revealing the racist and colonial component of the Spanish pride they celebrated. The artist nodded to the action carried out twenty-two years earlier by Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez Peña, in the context of the Fifth Centennial celebrations. Posing as ‘two undiscovered indigenous people’, both artists exhibited themselves caged before the curious and credulous gaze of tourists in the ‘seventies’ Discovery Gardens in Madrid, right next to the statue of Columbus. Far from being a singular event, petrified in the monuments, the artists demonstrated through parody that the colonial act of ‘discovery’ has been repeated and uninterrupted right up into the present. In this way they implicated the touristic spectacularization of the 1992 celebrations as a prelude to the intensification of extractivism and acculturation that would occur throughout globalization.

The fact that these actions converged on the figure of Columbus is, however, far from the result of a linear process free of contradictions. Since monuments affirm definitive and indisputable principles and values, ready to be collectively assumed or eventually rejected, it is worth paying attention to the shifting sands on top of which the statue stands, and explore how and why they have come to take on the meaning that we give them today.

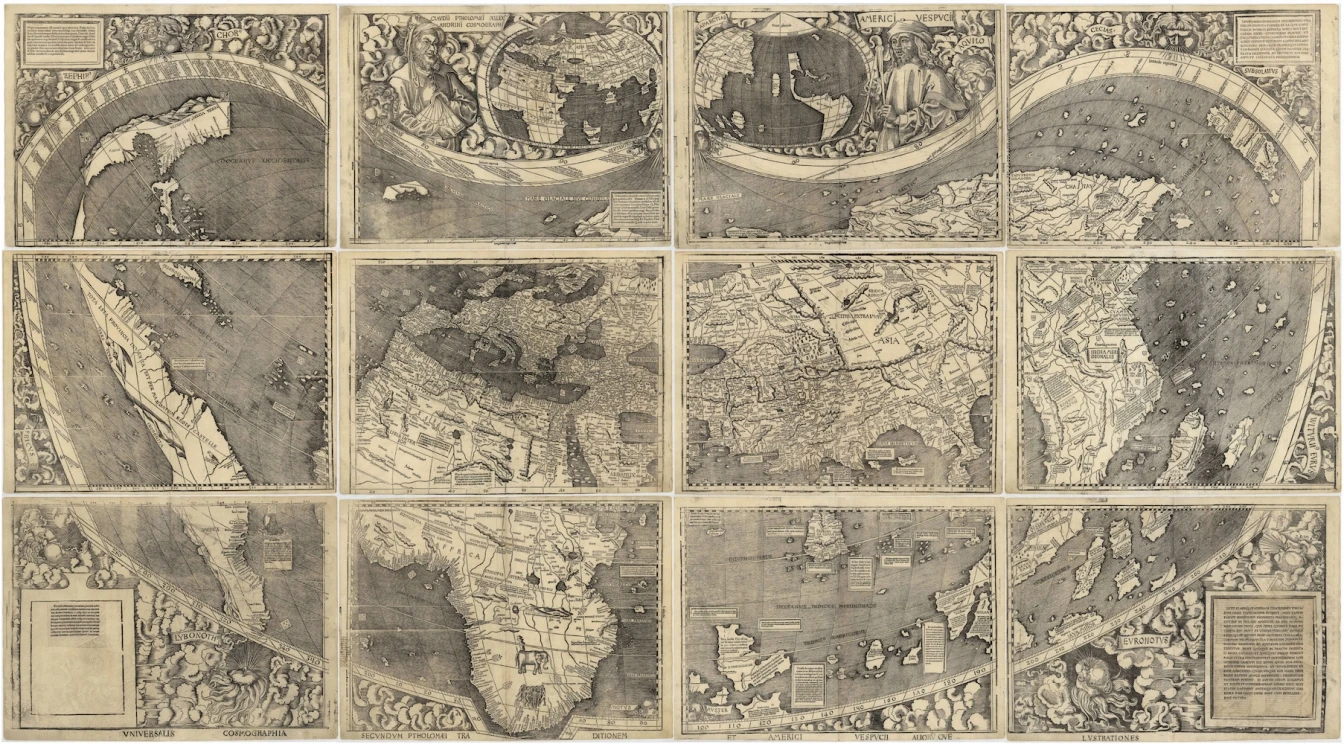

Universalis Cosmographia, Martin Waldseemüller, Strasbourg, 1507

Columbus had to wait almost four hundred years for Spain to make him the type of statue that Fernández de Oviedo evoked when addressing the emperor. At the beginning of the sixteenth century there was no monumental tradition in Spain capable of translating the chronicler’s Romanist rhetoric. If there were, it would hardly have been applied to Christopher Columbus ‘the discoverer’, given his arrest and the harsh litigation that enfolded him and his heirs over the wealth and government of ‘the Indies’. Such celebration was incompatible, in any case, with the Crown’s absolute ownership over the event and its implications, which did not allow for the bestowal of glory on anyone other than itself. The shadow projected on the figure of Columbus favored rather Américo Vespucio, who was recognized as Ptolemy's successor by Waldseemüller in his famous Universalis Cosmographia of 1507. Meanwhile, the coastal map of the recently baptized ‘America’ began to be crowded with Lusitanian and Castilian-Leonese emblems, according to the agreements signed between the two crowns in Tordesillas in 1494. Waldseemüller was not unaware of the role of Columbus in the discovery. However, that envoy of the Castilian monarchy could not be considered to be the modern equivalent of the Alexandrian geographer.

The proverbial confusion around Columbus regarding the nature of his discovery: ‘the Indies’ is a good metaphor for the contingency of a story whose fame was to be obscured in the writings of the royal chronicler Lucio Marineo Siculo, Opus de rebus hispaniae memorabilius, published in 1530. Neither the dates, nor the number of ships, nor the very name of Columbus appear correctly registered. That same text included the spurious episode of the discovery of an ancient Roman imperial coin on an American beach, irrefutable proof apparently of the old world’s historical dependence on the New World. The Genoese’s story would not be consolidated as a result of the will to tell an epic narrative of the Spanish conquest of the New World, but rather as the first version of many stories derived from the ‘adventures, misadventures and conflicts’ that accompanied an immeasurable and unspeakable process, to use the terms of the time. Despite the diaries and letters accumulated over his travels, the story of Columbus really begins to unfold after 1497, the year in which the monarchy decide to cancel his contract and Diego Columbus has to travel to Rome to speak to Julius II in support of his brother. The humanist Pietro Martire, in charge of establishing the official version of events, was persuaded by Columbus to finish the first part of the history in Latin as soon as possible, and to include information about the discoveries that Columbus himself had fed him. In fact, after the death of Columbus, the story only survives thanks to the publication of his De orbe novo in 1516.

Columbus Landing at Hispaniola, etching by Theodor de Bry illustrating the work by Girolamo Benzoni, Americae pars quarta. Sive, Insignis & admiranda historia de primera occidentali India à Christophoro Columbo, Frankfurt, 1594.

Twenty years after the death of the admiral there was a nulled attempt to resurrect Columbus as a foundational hero of the empire, worthy of being known by every ‘good Spaniard’. In 1526, in the same letter addressed to the Emperor Carlos that opens De la historia de las Indias, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo affirms, as its argumentative principle:

As is well known, Sir Christopher Columbus, the first admiral of these Indies, discovered them in the times of the Catholic Monarchs Don Fernando and Doña Isabel, grandparents of Your Majesty, in the year 1491 years [sic] [...] This service is today the greatest that any vassal could undertake for his prince and it is so useful to their kingdoms, as is well known. And I say so useful, because speaking the truth, I do not consider a man Castilian or a good Spaniard if he does not know this.

After the rhetoric that adorns this introduction, Oviedo aspired to forge a hegemonic narrative with very little chance of success. His emphasis on the epic dimension of the Columbian enterprise revealed a void at the heart of the conquest that became all the more evident the further the military invasion and the sordid human and material exploitation of the so-called ‘Indies’ progressed. To fill this gap, Oviedo offered the emblematic figure of Columbus as a prefiguration of himself, with all the ambivalence of an early colonial subject: on the one hand, Columbus was to personify the spirit of the monarchy, by birth and service, and, on the other hand, he was to represent, having been a member of the first generation, the Spanish settlers landing on the continent in 1513. Despite the irreconcilable differences between Oviedo and his contemporary Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas, both were in agreement regarding the epistemological and moral abyss that was the conquest, and both established the figure of Columbus as a node from which to weave a possible history. From Oviedo’s point of view, the recovery of Columbus as the sole and legitimate discoverer was as necessary for the empire’s thinkability as was the representation of the natural world that unfolded before the newcomers’ eyes and that he was preparing to take up in his work. As we know, Oviedo failed in his efforts in more ways than one. Cortés, and not Columbus, was to be the undisputed hero in the texts of Ginés de Sepúlveda and Lope de Gómara. Both imperial authors took much from Oviedo’s writings, but stopped when they reached the figure of Columbus, dissolving his role in the discovery with confusing circumstances and a haze of contradictory testimonies.

Allegory of America, Jan van der Straet, ca. 1587.

When the figure of Columbus reappeared several decades later in Theòdore de Bry’s famous illustrations of the conquest of America, it did so through the enemy Lutheran’s engraving chisel and in the context of the so-called ‘black legend’. Dressed as a soldier under the orders of the queen, lance in hand and sword at the waist, he is portrayed subjecting naked and naive indigenous peoples to the authority of the Spanish crown. This representation, distinct from the image of the ‘navigator’ to which we are accustomed, was a more fitting mirror image and the only one appropriate for the admiral and all those who followed him to the Indies, according to the Spanish narrative. By contrast, the narrative of the courageous entrepreneur and wise cosmographer that his heirs wanted to leave behind in that collage of stories that is La historia del Almirante (‘The Admiral's story’), was ultimately signed by his son Hernando and ended up being addressed to Italian readers. It was translated and published in Venice in 1571. Nevertheless, in Jan van der Straet’s famous drawing, America (ca 1575), it is Americo Vespucci who appears, waking up and naming the ‘new world’, personified by a naked woman reclining in a hammock. While America, barely standing up, only has her eroticized body, the cosmographer – standing before her – bears the symbolic attributes of the European civilizing force. Here present are not the lance and sword, as in Bry's Columbus, but an astrolabe and a flag with the cross.

In the discourse of the Hispanic nation, Columbus was not going to be awarded the star role that Camões gave to Vasco de Gama in Os Lusíadas, nor would Columbus gain the fame later bestowed on him within the imaginary of the young American republics, or the nascent Italy of the Nineteenth century. In fact, Columbus had to wait until 1846 to be the protagonist of the Canto épico sobre el descubrimiento de América (‘Epic Song about the Discovery of America’), whose author –Narciso Foxá– was an adopted Cuban, born in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Monument to Columbus, Genova, various artists, 1846-1892.

Monument to Christopher Columbus, Madrid, detail by Jerónimo Suñol, 1881-1885, uncovered in 1892. Image: Antonio García, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

The first European monument to Columbus was erected in his natal town Genoa that same year, in 1846, on the threshold of Italian unification. Columbus is represented as a person without military emblems leaning on a sea anchor. At his feet sits a naked Indigenous woman, although in this case her hands are full: a cross on the right and on the left a cornucopia. On one side of the pedestal, in large Latin letters it reads: DIVINATO UN MONDO LO AVVINSE DI PERENNI BENEFIZI ALL 'ANTICO (‘having imagined a world, he found it for the perpetual benefit of the old world’), demonstrating clearly the economic and extractive nature of the process initiated with the discovery in the minds of the compatriots. The additional nationalistic meaning of the monument is inscribed over the front: FOR CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS. THE HOMELAND. The visionary Genoese Columbus, once ‘unjustly’ imprisoned by the Spanish monarchy, now personified the powerful spirit of the new bourgeois nations that at that time aspired both to get rich and to free themselves from the chains of tyranny. It was in the context of this new patriotic-capitalist phase that Columbus recovered the starring role ‘usurped’ by Vespucio.

When the monuments were erected a few decades later in Barcelona and Madrid, it would be with a certain institutional laziness: the Columbus iconography was adapted to the ideological patterns and historical references of the time. Although bourgeois liberalism tried to make its way into a culture rooted in the Ancient Regime, our country continued to be more focused on venerating saints and virgins than leaders of the country. Remember that on October 12, Spain continues to celebrate the Virgen del Pilar, patron saint of Spain and of the Civil Guard.

Monument to Christopher Columbus, Madrid, detail by Arturo Mélida, 1881-1885, uncovered in 1892. Image: Jay Cross, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

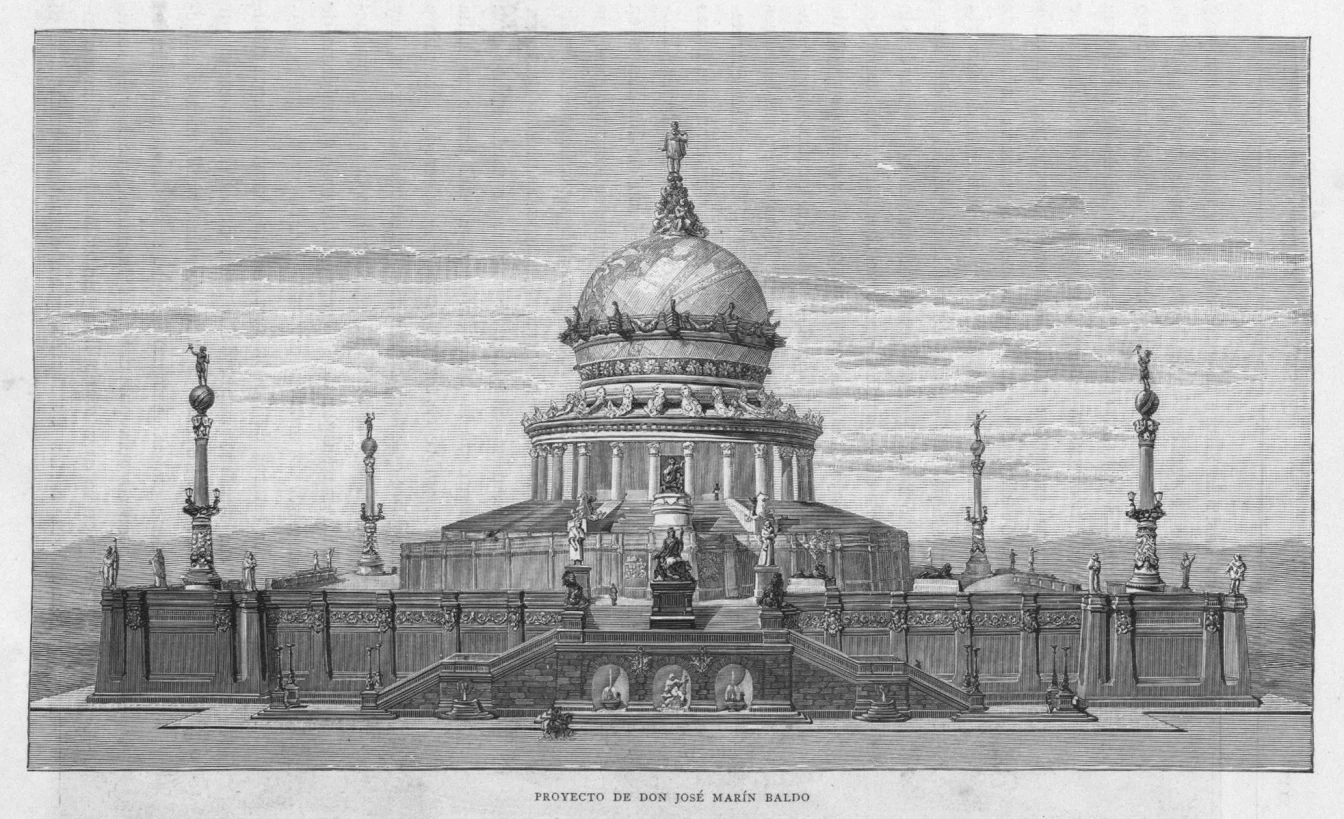

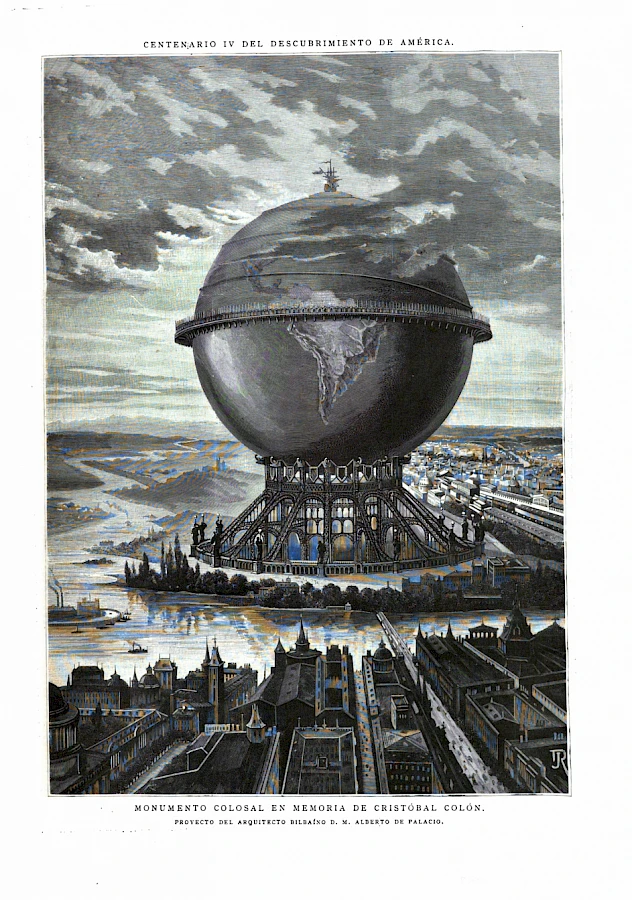

In the turbulent context of the First Republic, the federalist Barcelona City Council wanted a monument to Columbus to preside over the so-called Plaza de la Junta Revolucionaria, placing the intrepid hero as the antithesis of Spanish centralist nationalism. When fifteen years later the revolutionary fervour was suppressed, the Barcelona monument ended up being built at the end of Las Ramblas. The public interest was little in comparison to what was initially imagined. Murcian architect José Marín-Baldo had even less success. After training in Paris, he proposed the construction of an expensive cenotaph inspired by the Roman imperial mausoleums. He unsuccessfully presented the project again to Isabel II and later showed it in the Universal Exhibition of Philadelphia in 1876, to critical acclaim but ultimately it never manifested. The project proposed by the Basque architect Alberto de Palacio had a similar trajectory. The work was presented at the Columbine World Exhibition of Chicago in 1893, with the architect attempting to emulate the Eiffel Tower, built by his mentor for the 1889 Paris Exhibition. His enormous monument returned Columbus to the role that Waldseemüller had previously denied him: the maker of a new image of the world, now modern and technological; a world ready to be dominated according to the limits put in place by ideas of capitalist progress. The design was a 300-meter high metallic globe to be located on an architectural complex with libraries, museums and entertainment venues. In its true modernist expression, the project even came with an economic viability plan that referenced income from tourism. As in the case of Marín-Baldo, the recognition on the part of the United States did not result in the materialization of such an excessive project. It was also rejected when he proposed to build it in Madrid’s Retiro Park, next to the Crystal Palace that he himself had built a few years earlier for the colonial festivities of the 1887 Exhibition of the Philippines.

Monument to Columbus, José Marín-Baldo, 1876, part of José María Asensio, Cristóbal Colón : su vida, sus viajes, sus descubrimientos, p. XLV. Barcelona (1888?). José Marín-Baldo (1826-1891), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The image that would finally crystallize would be neither that of Marín-Baldo's classic hero, nor that of the pioneer of a worldly future, imagined by Palacios, but rather another historicist and explicitly self-referentially Hispanic. When the Madrid of the Restoration erected the monument located on the Paseo de Recoletos, it would do so with more economically and conceptually modest dimensions. The statue was placed on one of the disproportionate Gothic pedestals of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain and in accordance with the efforts to restore a degraded image of the metropolitan monarchy in full decline. His figure, ecstatically gazing towards the sky with open arms, mimics that of our mystic nationalists. The relief showing a chained Columbus that covers the pedestal of the Genoese statue was here replaced by allusions to the monarchy and the Catholic religion. The coat of arms, which was awarded to the admiral by the monarch and reads in Gothic letters ‘TO CASTILLA AND LEÓN A NEW WORLD GAVE COLUMBUS’, was given a privileged place. Despite such efforts at ideological translation, the handing over of the project to the City Council, which coincided with the fourth centenary of the discovery, was carried out without much fuss. Due to a change in fate, the ‘Discovery Pavilion’, which was to recover at last the Spanish-Colombian narrative from the history of science and technology at the ‘Expo 92’, suffered a devastating fire just two months before the opening of the ‘fair’ in Seville. This aspect was thus starkly eliminated from the celebrations from the fifth centenary.

Colossal Monument to the Memory of Columbus, Alberto de Palacio, illustration of La Ilustración Española y Americana XXXII, p.117, 1890. Image credits: Alberto Palacio, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The story of Columbus was destined from the beginning to accrue the meaning that the Spanish Monarchy gave de jure and de facto to the discovery, with the exception of Oviedo and Las Casas’ vain attempt to give meaning to the senseless expedition that ended up going beyond even the parameters inherited from the Crusades against Islam. The story has been told from very different points of view. Columbus’ ‘hagiography’ was plotted first in defence of the interests of his heirs and, only after a long hiatus, was it picked up by American pro-independence republicanism, from the South Antilles to the raging United States of North America, where the individualistic and pioneering spirit of Columbus found much affinity. Later, coloured with patriotic pride, Genoa claimed Columbus in the ideological context of the unification and the Risorgimento. The capitalist colonialism of the late nineteenth century once again began to see itself in the figure of a white, enterprising man of European origin, ready to dominate the world through his supposed racial, cultural and technological superiority. The ‘re-Spanishization’ of Columbus, as I have reconstructed here, was relatively late, imposed defensively and the result of many negotiations with different versions of the story that had once been generated precisely to separate ‘the discovery’ from Spanish national discourse.

It is interesting to note that despite the violence and racist inequality that prevails in the United States, the monuments to once revered Columbus are gradually being eliminated through the implementation of democratic decisions being made in city councils from Los Angeles to New York, passing through Denver, Phoenix, Albuquerque or Minneapolis. Recently, the statue of Columbus and Isabella I of Castile was removed from where it once presided over the California Capitol rotunda. This move was part of a general withdrawal of images that are offensive to the indigenous populations, to the extent that these statues celebrate their genocide. It is the result of a long process of anti-racist activism and protest and the defence of civil rights that speaks to us of the plasticity that North American society still maintains.

In 2010, coinciding with the second centenary of Latin American independence, the Principio Potosí (‘The Potosí Principle’) exhibition opened at the Reina Sofía Museum, a temple of post-dictatorship Spanish modernity. The German-Bolivian curatorial team tried to definitively crack the ‘egg’ of Columbus by showing that there is a single and uninterrupted process of expropriation and exploitation that continues into the present and on a global scale. Dismantling the rationalist myth of progress, they pointed out that the substance of what we call ‘modernity’ was forged in the process of ‘primitive accumulation’ that was initiated violently by the Spaniards in the mines of Potosí in the sixteenth century and is perpetuated by capitalism today. In this way, they undermined the enlightened foundations of the independence narratives that were celebrated at the time. Following Enrique Dussel, the modern subject is configured as ego conquiro through a dialectic of previous domination inseparable from the supposedly Christianizing and civilizing mission of Spain and the West. Having burst the seams of the Enlightenment project, modernity would reveal itself in all its baroque, eccentric, mestiza and violent rawness, although not devoid of disruptive and emancipatory ferments.

The contemporary anti-colonial and anti-racist movements know, as do the curators and artists of The Potosí Principle, that the enterprising and cosmopolitan Columbus and the soldier Columbus at the service of Spain are two sides of the same coin; constitutive parts of a process that has carved our social space out using the chisel of domination and that has depleted the planet as a whole. The ‘barbaric’ act of tearing down the statues, whether metaphorically or literally, should infect us with some of their rage and lead us to dismantle once and for all the symbols that support our White European superiority, an essential and urgent gesture if we want to imagine and build a liveable world.

Exhibition view of 'The Potosí Principle. How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?', Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, 2010. Photo by Joaquín Cortes and Román Lores.

Article originally published in Spanish in 'CONTEXTO Y ACCION', 25 March 2021 https://ctxt.es/es/20210301/Firmas/35353/derribo-estatuas-Colon-racismo-colonialismo-blanquitud-Jesus-Carillo.htm

Translated to English by Rebecca Close.