Temporal Collage and Producing Escape: What is the relationship of modernization to boat living?

Harun and Jamie departing from St Pancras Basin aboard Zoar, 2020. Photo by R. Nordin.

What is the relationship of modernization to boat living in London today? The fundamentals of narrowboat living in Britain have changed minimally over the course of the twentieth century: burning firewood or coal for heat; a metal bucket hanging overboard for keeping dairy items cool rather than electrochemical refrigeration; being itinerant, slow travel… Tractor engines may have replaced horses towing boats (hence the term ‘towpath’; there are still bridge pillars on Regents Canal scored by the ropes of the past), and the installation of solar panels has become more common since the 1970s, but otherwise, there has been a constancy in boat design and boating practice. This is in contrast to the changing construction practices and new materials accompanying successive waves of architectural ideologies and styles over the last century – through Modernism, Postmodernism and Neo-Futurism, to wherever we presently find ourselves.

Infrastructural and transitional modernization projects, such as the development of the National Grid (the first and ongoing system operator of Britain’s electricity and gas supply, which initially installed 26,000 electricity pylons by 1933), in turn altered the aesthetic of the British landscape and expanded the lexicon of the country’s visual imagination. London’s sewage system had been completed just sixty years earlier: two thousand kilometres of brick tunnels taking raw waste directly from houses with a further 130 kilometres of interconnecting sewers. It is easy to cast these subterranean structures carrying effluence as a spatial and mental shadow to the picturesque network of canals and rivers above ground, but current protests against the pumping of raw sewage into the waterways today recognise their intersection. The sewer system was funded by the government whereas the canals were largely paid for by private syndicates. The construction of the canals began in the seventeenth century to capitalise on demand to ferry produce between ports, such as London and Bristol (those receiving and sending products to and from colonial territories), and inland British industrial centres, such as Birmingham or Coventry. Nonetheless, the emergence of both systems was part of a transition from traditionalist and localised solutions to master-planned, national-scale structures. Once trains superseded canals in their speed and efficiency by the end of the nineteenth century, the waterways slowly became redundant as a network for trade. From this perspective, boat living on the British canals is a byproduct (and beneficiary) of a defunct distribution system, one that came to an end in the late stages of the Industrial Revolution.

The railways and the National Grid were both accelerators: of the movement of bodies and products, in the case of the former; and of production and communication time – for those with the means to exploit it, through new access to electricity in commercial, industrial and domestic spaces – in the case of the latter. Yet these contributors to modern living in Britain as we know it – access to power, effective sewers, improved rail and road travel – did not directly affect the conditions of boat living.

Slipping through the net of these key drivers of modernity, so narrowboat living becomes para-modern. On the water, the tasks of more than a century ago continue to be enacted – dealing with one’s own waste, for example, and vehicle maintenance. More so than ever, boat living in London is a counterpoint to the city’s verticalities (think not only of the high-rise, but of mounds of capital) and the outsourcing of the labour of living provided by modern infrastructure.

On an aesthetic level, the casual roping of boats to one another, or pinned to the winding towpath, defies the archetypal modern grids of car-park spaces or ‘new towns’ like Milton Keynes, harking back to earlier spatial orders like pre-nineteenth-century cemetery plots. The higgledy-piggledy arrangements of boats are mirrored by their roofs; the practice of communal, DIY/DIWO repair and upkeep might evoke both steampunk and a Hollywood vision of the post-apocalyptic. The sci-fi trope of hacked twentieth-century cars is not so distant from the improvised repatching and rewiring of a boat’s interior and its ageing systems.

Nonetheless, the image of self-sufficient, contained isolationism associated with being off-grid is inaccurate for boaters today (perhaps it always was). Living on water does not mean you are not a beneficiary of infrastructural systems: electronic devices are charged from the mains of coffee shops, pubs, studios or work places wherever possible; items are ordered online to an address on land; Calor Gas canisters arrive via delivery car, and so on. Moreover, the interconnectivity of our bodies through air- and waterborne diseases emphasises how our health does not solely depend on the strength of our immune systems but on the people around us; effective waste and hygiene management, reducing spreadable disease, is vital, no matter what kind of community you live among. The para-modern is a permeable condition.

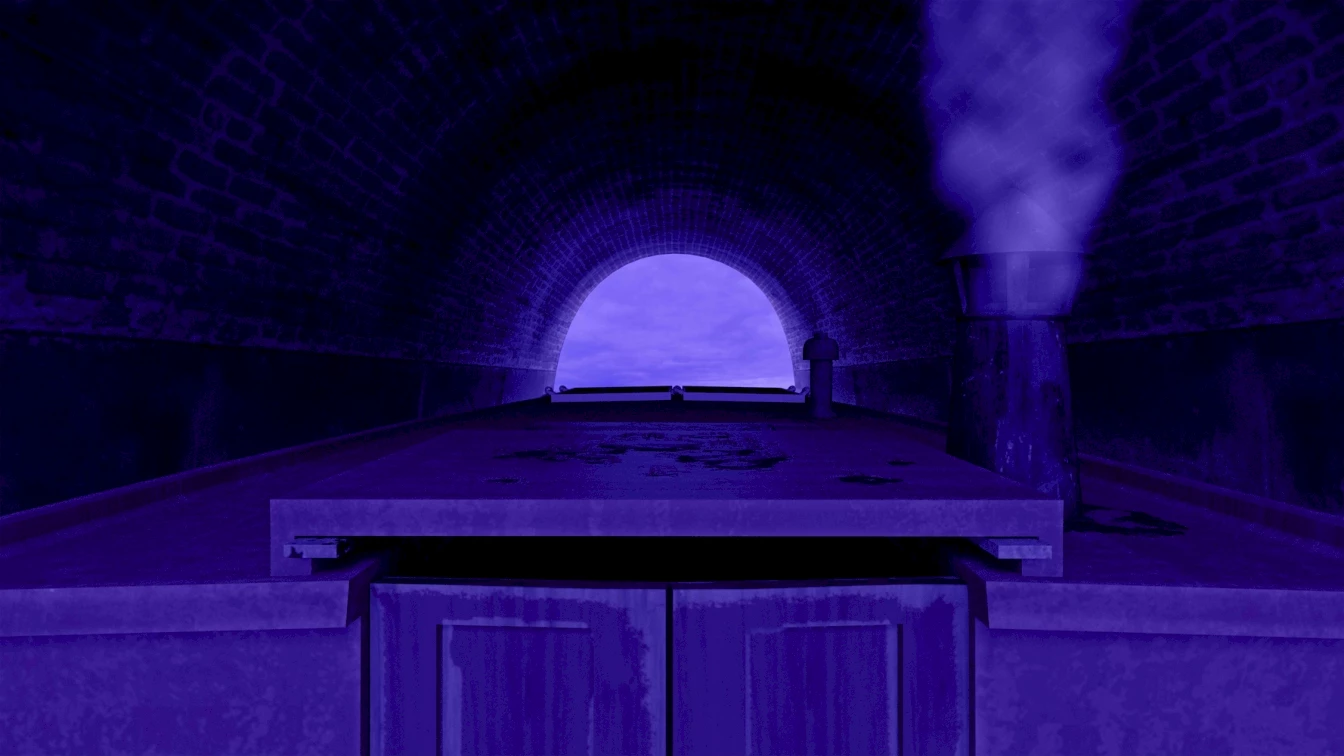

Harun Morrison, Zoar Returns (digital still), 2021.

Long before Le Corbusier declared, ‘A house is a machine for living in’, in his 1920s publication Towards an Architecture, narrowboats had functioned as such. Narrowboats and canals are the products of engineers as much as architects; they embody the edict ‘form follows function’. Yet narrowboat design would never embrace the monochromatic and moral aspirations of textbook modernist building. If demodernization involves, according to historian Yakov M. Rabkin, the ‘lasting degradation of material, health, and cultural conditions in a formerly modernised society’ and ‘a return to “premodern” forms of life and collective identities’, boat living cannot be demodernized, because it never really became modern.1

Boat living exemplifies a way of life as a site of temporal collage. Across generations, a bric-a-brac of technologies accumulate in the narrowboat: tractor engine, solar panels, stove, Wi-Fi router, radio, plastic cassette toilet. Contemporaneity seeps into boat living through its administration: the registering of vessels, the licences, fees and databases that catalogue the various maintenance and safety surveys – all those less visible organising structures that regulate living on the water in the twenty-first century.

Demodernization is typically theorised as happening in specific places: across industrial towns in the post-Soviet landscape or among the collapsed factories and their interdependent workforces in Detroit. It is the violent reaction to extractive growth elsewhere. In his essay ‘From Demodernization to Degrowth’, Bertrand Cochard posits a ‘subjective demodernization’ that is self-initiated, conceptual and internal, rather than imposed on citizens through extreme economic forces beyond their individual agency: ‘Demodernization as decolonization is only about refusing all the associations of thoughts (e.g., identification between growth and development) that modernity ingrained in our minds.’2 Cochard suggests that demodernization does not need to be a top-down imposition at a point of crisis, but rather can be a transitory process we consciously move through, in the same way that decolonization can be understood as an unceasing practice rather than a final destination or event. Refusal of a final destination parallels the boater as ‘continuous cruiser’ – the administrative name for the type of boating licence I have, where you have no fixed mooring and are obliged to move fortnightly. Boat living and art-making offer an imaginative, regenerative space to cultivate a self-instigated and internalised ‘subjective demodernization’.

Harun Morrison, Zoar Returns (digital still), 2021.

I attempt to dissect the idea of temporal collage through my autoethnography as a boater on my narrowboat liveaboard, Zoar, originally built in 1975. I have owned this boat since 2019, having lived on and off the water for the past five years, previously on another narrowboat, Bruno. I am currently exploring these reflections through the development of a video game, Zoar Returns. Pictured are stills from the short trailer for this game-in-the-making. Zoar is the unmanned protagonist, modelled on my boat. The locations in the animation include St Pancras Basin in Kings Cross, Maida Hill Tunnel on Regents Canal, and an aerial shot of the narrowboat passing the Banana Warehouse in Digbeth, Birmingham. It takes after trailers for video games on YouTube in the simulation genre, such as 18 Wheels of Steel, a trucking game, and Microsoft Flight Simulator. The blue light in the tunnel alludes to a line describing ‘ultramarine skies’ from a translation of Rimbaud’s poem ‘The Drunken Boat’ (1871), in which the inner voice of an unmanned vessel shares a transcendental vision as it slowly fills up with water. ‘The Drunken Boat’ can also be thought of as a kind of simulation (though not an interactive one) – the simulation of the imagined consciousness of a boat in delirium. The virtualisation of boating that the game promises is an attempt to decouple the spirit and theory of boat living from the actuality of being on the water; giving space to the conceptualisation of boat living as practice, and loosening the ableist narrative around good seamanship.

In spring 2021, while developing the trailer, I converted my boat into a camera obscura. Images of the waterways outside were projected into the blacked-out boat’s interior through a window reduced to a pinhole, while light-sensitive paper enabled me to capture these images, later developed manually in the boat-turned-darkroom. These two modes of image-making – contemporary digital animation and the centuries-old camera obscura – play out my sense of the mixed temporalities of boat living. While the animation depicts the boat from the outside, the photographs are produced inside it, so that the boat’s interior comes to contain its exterior.

These representations affirm boat living as itinerant, composite and pluralistic, alternatively understood as a shifting set of relationships: the interplay between the water and the non-human life (vegetal and animal) that surrounds and supports the boat; the manmade infrastructures of the canal and river network; the human relations between the boaters; and the administrative and legal frameworks that regulate boating and determine its relationship to the land and to mobility. There was little space for the itinerant under modernist visions of futurity, besides an emphasis on the modularity of building structures or the movement of bodies in cars. Even in the Walking City (1964), a playful proposal by Ron Herron of Archigram where giant built platforms move around on telescopic legs, it is the structures – rather than humans – that are set in motion.3 Modernization has forced nomadic Indigenous peoples across multiple geographies to assimilate into the sedentary modes of living enforced by privatised and anti-civic policies and ideologies of the built environment – think the reduction of commonland, defence architecture, the removal of water fountains and public toilets.

On the UK inland waterways today there are rising tensions between their administrative body, the Canal & River Trust and ‘continuous cruisers’ like myself, leading to many protests including those organised by the National Bargee Travellers Association, ‘who seek to represent the interests of all itinerant live aboard boat dwellers.’4 Recently, these debates have involved the reduction of mooring space for continuous cruisers over those with permanent moorings (which generate more income), ultimately curtailing the historic culture of travelling live-aboard dwellers.

There are an estimated 600,000 Roma, Scottish, English and Irish Travellers in the UK who have faced generational discrimination that persists today. I intuit this to be partly rooted in the way dominant society perceives their mode of living as an existential threat to orderliness and stability; an erroneous logic that moralistically equates sedentariness with good standing. Nomadic and itinerant lives have different relations to accelerated world-building in the twenty-first century than in pre-industrial eras. To be itinerant in the built-up zones of westernised nation states is no longer necessarily motivated by seasonal change or the pursuit of particular herds of animals. Could it be that the itinerant, subjective demodernizers, by resisting the totalising capture of modern infrastructure, produce escape? Not escape as an act of feigned magic, but as a perpetually unstable yet cultivated condition? If we recognise itinerancy as a state of desire, which should not be socially or legally repressed, then the spirit of boat living might be practiced in settings beyond the canals, whether this be in video games, in a municipal housing complex or on a desert mountain.

Harun Morrison, Boat as Camera, 2021. Eastside Projects, Birmingham. Documentation photo by Stuart Whipps.