The Noise of Silence or ¿Por qué no te callas? (Why don't you shut up?)

Ines Doujak, Not Dressed for Conquering / HC 04 Transport, sculpture, 2010-ongoing. Courtesy of the artist.

*Spanish King Juan Carlos I to Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez at the 2007 Ibero-American Summit in Santiago, Chile.

Mis-representation1 and vulgar reductionism are increasingly common forms of censorship in Europe at a time when a loss of nerve has led to critical judgment being replaced by the tyranny of opinion. The sculpture Not Dressed for Conquering / HC 04 Transport, part of the project Loomshuttles / Warpaths (2010-ongoing), was subjected to censorship at the 2014 Biennale in São Paulo and attempted censorship at the MACBA in Barcelona in March this year. This censorship constituted a denial of the history which the work explores: the continuum of colonialism from the past to the present, specifically that of Spain in Latin America, and the involvement of Nazis in the sub-continent's era of dictatorships. In Spain, history itself is still repressed. Demanding to be heard, the voices of the dead of the Civil War demanding to be heard were in effect censored by the right wing People's Party government in 2011 when it abolished the Office of Victims of the Civil War and the Dictatorship, which coordinated the exhumation of the remains of those who disappeared.

As an Austrian artist, one is especially aware of the dangers of selective historical amnesia. This was articulated for us by the writer Elfriede Jelinek when she quote the Brothers Grimm fairytale of the obstinate girl whose hand keeps growing out of the grave and protests against being dead. Thus she became a metaphor for the victims of genocides who resist the disappearance of our cultural memory. "We are living on a mountain of corpses and pain", Jelinek wrote (1995). Or listen to the talking knee of a certain Corporal Wieland killed at the battle of Stalingrad, as recorded by Oskar Negt and Alexander Kluge in Die Patriotin coming back to set the record straight: "I have to clear up a fundamental misunderstanding, namely, that we dead are somehow dead. We are full of protest and energy" (Negt and Kluge 1979).

In the sculpture, the alive and the dead are not separated in different roles but desperately nested into each other so that the moments of overlap and encounters cannot be neatly confined. The border between the present and history, between objects and bodies, between the three bodies are blurred, and what we might see is not several parts but one.

Around the same time in the 1970s, while Juan Carlos I was being groomed by the dictator Franco to make the necessary adaptation of the state after his death, Domitila Barrios de Chúngara was a leader of the Housewives' Committee in the Siglo XX mine camp in Potosí. After she was invited to attend the United Nations' International Women's Year Tribunal in Mexico in 1975, she became well known. On 28 December 1977, she joined the hunger strike launched by four miners' wives – Aurora de Lora, Nelly de Paniagua, Angélica de Flores and Luzmila de Pimentel – and their fourteen children, in the offices of the Archbishop of La Paz demanding that the government democratise the country, withdraw army troops from the mine regions, and grant unrestricted amnesty to political and union leaders. They were backed by priests, workers, students and peasants who kept joining the hunger strike. Together with the waves of protest that spread through the country, they succeeded in forcing the military dictatorship of General Hugo Banzer Suárez to step down and call general elections. She died in 2012, having lived to see a democratic Bolivia, despite further coups and repression. Even though she was persecuted, jailed and tortured, she was never silenced.

One such coup, that of 1980, financed by drug traffickers and narco-dollars, led by colonels Luis García Meza and Luis Arce Gómez, left a trail of dead and wounded. Paramilitaries, recruited by Klaus Barbie, were used by the colonels to help them take over. Barbie, the Butcher of Lyon, reached Latin America with the aid at different points of the US Army's Counter Intelligence Corps, the Vatican, and the "Werwolves". As well as being implicated in the cocaine-arms trade, he was appointed to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel within the Bolivian Armed Forces, as a reward for having been a lead teacher of torture techniques for Bolivian dictatorships.

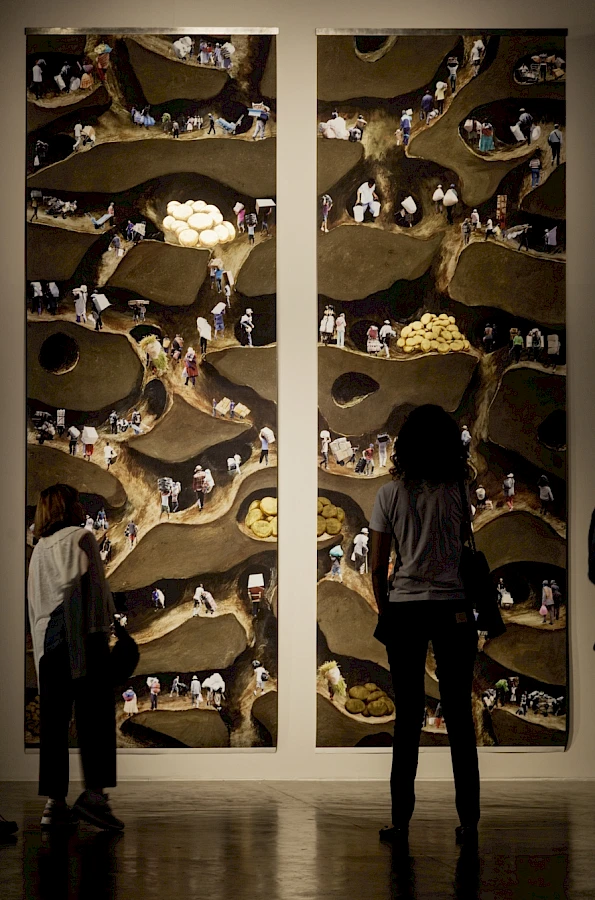

Ines Doujak, Not Dressed for Conquering / HC 04 Transport, cloth design, 2010-ongoing. Courtesy of the artist.

80 million people were living in the Americas in the 15th century. By the middle of the following century, only 10 million of them were left. Eight million died in the silver mine of Potosí alone, Indians, who as Karl Marx described, lived only to "disappear from the face of the earth" (Marx 1906). From then on, silver bankrolled the Spanish monarchy for the next 200 years; kick-started European capitalism; and provided what was needed for the extension of European colonialism to Africa and Asia, a commodity desired by its rulers and traders.

In the essay Discourse on Colonialism published in the early 1950s, Aimé Césaire described the conflict between the colonisers and the colonised: "What am I driving at? At this idea: that no one colonizes innocently, that no one colonizes with impunity either; that a nation which colonizes, that a civilization which justifies colonization—and therefore force—is already a sick civilization, which irresistibly, progressing from one consequence to another, one denial to another, calls for its Hitler, I mean its punishment" (Césaire 1972).

The Afro-Colombian journalist Rosa Amelia Plumelle-Uribe followed Césaire's outline of the colonialism-National Socialism continuum. In White barbarism: of colonial racism and racial policies of the Nazis, she noted: "The dungeons in the fortresses on the West African coast remind one of crimes against humanity much like the remains of Auschwitz do; slave labor on the sugar plantations of the New World is comparable with the forced labor of the concentration camp inmates" (Plumelle-Uribe, 2004). She denounced how the black-skinned victims of colonialism and their descendants are still discriminated against by the descendants of the perpetrators.

The bed of broken German army helmets, the figure of a werewolf and the cornflowers so favoured by Adolf Hitler, and modern day neo-Nazis and deputies of the Austrian Freedom Party, in the sculpture, highlight this historical trajectory and takes it further into the neo-colonialism of now.

Hitler used the pseudonym "Wolf" on occasions, and "Werwolf" was the name given to the Nazi guerrilla force developed from 1944 onwards. On 23 March 1945, Joseph Goebbels gave the "Werwolf Speech", in which he urged every German to fight to the death. At the end of the war, "Werwolves" were used as part of a Nazi "underground railroad", facilitating travel along escape routes, the so-called "ratline" used by Nazis like Barbie.

Ines Doujak, Taquile, photography, 2006. Courtesy of the artist.

The sculpture belongs to the long-term and ongoing investigation Loomshuttles / Warpaths which explores the complex relations of cloth, clothing and colonialism from earlier to contemporary forms of globalisation. It is part of an installation containing many parts, among them a cloth design showing present day human load carriers from all parts of the world in a network of ant tunnels with caves where golden eggs are piling up. This cloth was made into bags, as a critical expression of the current use of David Ricardo's early 19th century Law of Comparative Advantage. The law is a piece of dismal conjuring suggests that Free Trade is good for everyone, even though there never was anything free at the time in a world of invasions, colonies and slavery, and when today bilateral and regional trade agreements between the more and the less powerful are the norm. Free market ideology serves to re-legitimise colonial hierarchies and, from a North European point of view, decolonisation in Latin America basically means access to markets for Western capital and its financial infrastructure, investments on the cheap, and cheap raw materials.

My work aims to contradict neoliberalism's constant response to the crimes of colonial exploitation: "oh that was then"... I am particularly concerned with the role of Spain in Latin America then and now. A NOW in which Banco Santander is the dominant banking network on the continent. This is not insignificant when it is finance capital that is the orchestrator of neoliberalism. In the 1990s, Spain became the biggest foreign investor in the continent after the United States. Faced with both increased competition within Europe and seeing the opportunities presented by the Latin American "debt crisis", Spanish companies snapped up privatised cash-strapped Latin American banks and utilities at fire-sale prices. Since the 2007-8 crisis, Spanish investments in and revenues from the continent have increased three times. It has been called "the re-conquest" and involved a marketing campaign led by a constant visitor to the continent, the former King Juan Carlos. Occasionally this has hit the headlines as when the King, used the "tu" form, as if to a child, to tell President Hugo Chávez to shut up. The boiling point had been when Chávez – with some justification – called Spanish People's Party Prime Minister Aznar, an enthusiast for the Iraq invasion of 2003 and former member of the Falangist youth organisation, a fascist. Not coincidentally, this occurred at a time when the Spanish neo-colonial expansion was confronted with Latin American demands for the re-nationalisation of utility and energy companies on the grounds that they were being asset stripped. Since then, despite Spanish diplomatic pressure and threats, such re-nationalisations have taken place in Bolivia and Argentina.

And the Wolf is still present as is shown by an attempted coup in Venezuela in 2002, and the "modern" coup d'états carried out in Honduras (2010) and Paraguay (2012) in which democratically elected governments were ousted without overt military violence by the power of money and its media without eliciting any condemnation from the West.

This is the now.

An artist should not have to explain her or his work. But the recent instances of prurient mis-representation, self-interested righteousness, and what I would call the tyranny of lazy opinion, forced me to give this account of what has gone into the work to counter what I believe are the unstated but real limits of what art is allowed to do and which constitute the censorship that has become prevalent in a world of the neoliberal monologue.

References

Jelinek, E. 1995, Die Kinder der Toten, Rowohlt Verlag, Berlin.

Negt, O. and Kluge, A., 1979, Die Patriotin, Texte/Bilder 1–6, Zweitausendeins, Frankfurt am Main.

Marx, K. 1906, Capital. A Critique of Political Economy (Das Kapital), Charles H. Kerr and Co., Chicago.

Césaire, A. 1972, Discourse on Colonialism, trans. J. Pinkham, Monthly Review Press, New York and London.

Plumelle-Uribe, RA. 2004, Weisse Barbarei: Vom Kolonialrassismus zur Rassenpolitik der Nazis (White barbarism: of colonial racism and racial policies of the Nazis), Rotpunktverlag, Zürich.

David R. 1984, "Law of Comparative Advantage" in L. Torrens (ed.), The Economists Refuted and Other Early Economic Writings, Kelley, New York.