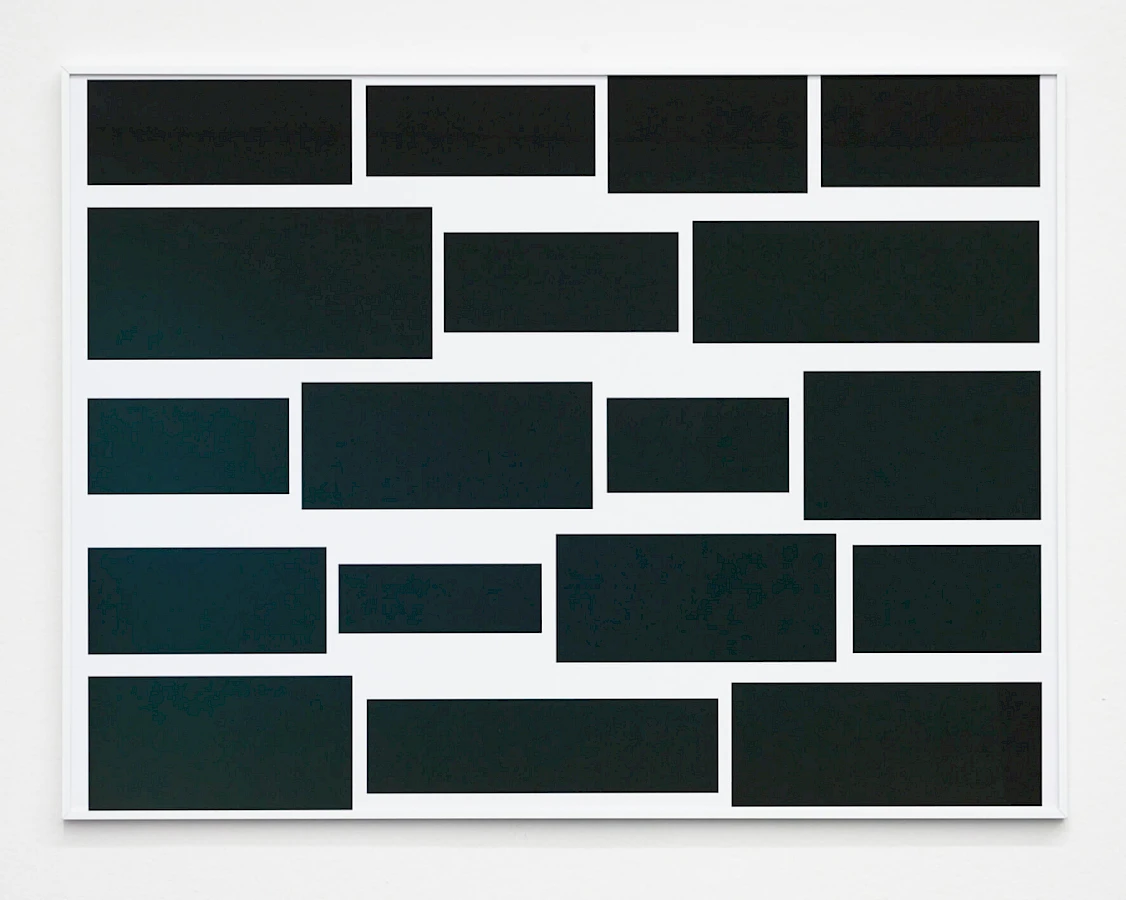

Sean Snyder, Image Search (Guernica), 2017, framed b/w archival print on matte paper, 90 x 120 cm. Courtesy Sean Snyder.

Tu n'as rien vu à Hiroshima.

–Marguerite Duras, Hiroshima mon amour

Gernika, Coventry, Leningrad, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Grozny, Aleppo, Mariupol … ‘Never again.’ Time and again.

It is a new and unwanted experience to hear bombs exploding on the outskirts of Kyiv at 5 o’clock in the morning of 24 February 2022 – and then to hear more explosions, time and again.

‘It is exactly the same time, again.’ This phrase is repeated by Kyivians in make-do bomb shelters as the memory of the first Nazi bombing of the outskirts of Kyiv on 22 June 1941 resurfaces in the shared time of these newly formed underground communities. I gradually get used to the nauseating sound of the siren announcing an imminent air strike, over and over again.

One week into the war, when drinking water becomes a scarcity in the city, it is again a new and unwanted, but this time accepted, experience to evacuate from Kyiv. I am leaving behind my home, my books, my writing table, without knowing if I will ever be able to return to this space where I have lived my life. It is another newly shared experience to escape with the bare necessities and become an internally displaced person.

As I write these words, one month into the war, I seem to have regained the ability to express this experience, to share it with the world. It was too unbearable before. It has been a month of feeling a bleeding pain in the face of aggression against the country to which I belong. It has been a month of an acute awareness that we are being killed simply because we exist, or, to be more precise, because we ‘do not really exist’ in someone else’s illusory world, in which we are perceived as an irritating obstacle to their ‘Grand Cause’. It has been one month of facing the unbearable lightness of being. The famous title of Milan Kundera’s novel finally makes sense as a reference for the real-time unfolding of damaged life. Time and again.

As I reread my brief and somewhat cryptic essay on Maidan, written eight years ago (reproduced below, without changes, as a kind of a document of that time), I am struck by the oracular obscurity of my own writing. Could I have been more clear, more precise? It seems to me that the deliberately prophetic tone of this essay was not so much a response to the word Prophetia, the title of the catalogue for an exhibition of the same name, for which my essay was originally written.1 It seems, rather, that it was the only way available to me to express the painful frustration shared by many Ukrainians at the time. Frustration with the artists and curators pursuing an ‘emancipatory’ agenda paid for with Russian mafia-capital. Frustration with the left-wing intellectuals and politicians blindly repeating Putin’s geopolitical mantra about the ‘expansion of NATO, which threatens Russia’. The deliberate obscurity of my essay on Maidan was the only way I could point to the invisible drops of Ukrainian blood on the hands of these individuals so happily ignorant of their blindness, the only way to cautiously reveal the truth that such blindness kills. Time and again.

To get a taste of this dissipated blindness, read, for example, Seumas Milne’s columns on Maidan for The Guardian, published during the events of the Ukrainian popular uprising and Russia’s first overt aggression against Ukraine.

In Milne’s columns, and in numerous publications like them, one finds a perfect set of instruments for the post-truth era. Take, for example, the flagrant reversal performed by Milne in the wake of Maidan. ‘It’s not Russia that’s pushed Ukraine to the brink of war’, read the title of his column published on 30 April 2014. Today it reads not as a pathetic prophecy, but as a direct statement of Putin’s murderous intentions projected onto Ukraine and disguised as the concerned ‘opinion’ of the establishment of the European Left – Seumas Milne would soon become the UK Labour Party’s director of strategy and communications. This is a perfect example of how Putin’s total art of political gaslighting was shared by the most vocal part of the Left in Europe and elsewhere.

Another example of this political gaslighting is evident in the way Milne turns the meaning of Maidan on its head. In his opinion, Maidan was not an uprising of the Ukrainian people against a pro-Russian president imposing the indignity of mafia-capitalism, but the result of a Western conspiracy. Committed to a geopolitical perspective, Milne ignores the agency of the Ukrainian people:

The threat of war in Ukraine is growing … The US and the European Union step up sanctions against the Kremlin, accusing it of destabilising Ukraine. The White House is reported to be set on a new cold war policy with the aim of turning Russia into a ‘pariah state’.

That might be more explicable if what is going on in eastern Ukraine now were not the mirror image of what took place in Kiev a couple of months ago. Then, it was armed protesters in Maidan Square [sic!] seizing government buildings and demanding a change of government and constitution. US and European leaders championed the ‘masked militants’ and denounced the elected government for its crackdown, just as they now back the unelected government’s use of force against rebels occupying police stations and town halls in cities such as Slavyansk and Donetsk.2

Here Milne not only erases any meaningful difference between a genuine popular uprising and its simulation by the Russian government, he also cynically sides with the latter. In the name of KGB-style ‘simulacra and simulation’, Milne denigrates the very idea of a popular uprising, the very possibility of the people’s agency. Such reversals were parroted by Putin’s useful idiots in Europe and elsewhere ad nauseam.

The Ukrainian people had to confront this political gaslighting time and again, particularly in the left-wing press. Way too many left-wing intellectuals imagined that Putin could embody ‘a possibility of plurality’, ‘another perspective’, and ‘an alternative’ to the ‘axiomatically correct ideology of the West’, without realising that they were hopelessly stuck in the last century and its distant reverence for the Russian Revolution. Of course, there were other voices on the Left. But those like Milne’s dominated the discussion. Some of these dominant voices – including, sadly, Noam Chomsky3 – still echo the familiar mantras of NATO and Western expansion, which, they say, threatens Russia ‘existentially’.

What perplexed me, time and again, was that these left-wing intellectuals never seemed to bother to consider that the Ukrainian people have the right to decide their own future. These left-wing intellectuals tended to switch blatantly to a geopolitical point of view as soon as they looked beyond the borders of their own first-world countries. Eager to criticise Western imperialism, they were unable to recognise its Russian version. Isn’t this also a perverted form of imperialistic thinking?

For these left-wing ‘imperialists in reverse’, the people’s agency seemed to be relevant only as far as the EU’s borders extend. Moreover, these left-wing critics of Western imperialism seemed to be as blind to the aspirations of the Ukrainian people as they were to the actual misery of the Russian people. They used ‘Russia’ as a helpful abstraction to equate Putin with the Russian people, who, in fact, were abused and exploited by their own government, time and again.

Instead of siding with the people against their real oppressors, these left-wing intellectuals let themselves be seduced by Putin’s total art of political gaslighting. How else can one explain their reluctance to criticise Putin, or even their endorsement of him as an ‘alternative to the West’? How else can one account for their willing blindness to Putin’s ‘Grand Cause’ to ‘Make Russia Great Again’?

This willing blindness was what I wanted to highlight in my Maidan essay, eight years ago, by explaining the semantics of the Ukrainian noun ‘maidan’. My frustration with the common English-language tautology ‘Maidan Square’ – used by Milne in the above-cited piece – was the least painful frustration. Yet I wanted to show that this tautology is a symptom of a deeper process: the tendency to erase the agency of the Ukrainian people. So, let me explain it again. The noun ‘maidan’ is part of the proper name of the central square in Kyiv, Maidan Nezalezhnosty (Independence Square). But ‘maidan’ is also a generic word in the Ukrainian language. On the most basic level, it is a synonym of ‘square’ (ploshcha). Yet there is more to it than this, because Maidan is not just part of the name of the actual Kyiv square, or a synonym for the word ‘square’. It also has a political dimension: in conceptual terms, it refers to the potential for people to take common action in the city square. ‘Maidan’, therefore, contains within it the concept of the agency of the people.

The distinction between a ‘square’ and a ‘maidan’ seems to be specific to the Ukrainian language. It is absent from Russian and, to my knowledge, from other European languages. But it is important to understand ‘maidan’ not just as a nuance of the Ukrainian language, but also as a real alternative to the geopolitical perspective that excludes the agency of the people and thinks solely in terms of borders containing square metres and kilometres. The use of the tautology ‘Maidan Square’ can be seen, at least in the case of Milne and the like, as a symptom of their inability to distinguish between the place of common action performed by the people and the physical territory invaded by the government.

Put more simply: Maidan as a historical event realised the conceptual potential of the word ‘maidan’ as a place of a popular uprising. Maidan embodies the agency of the Ukrainian people. This is crucial to understanding that it is not NATO but the Maidan that Russia-as-Putin fears the most. Putin’s only goal is to secure oligarch-dominated mafia-capitalism in a ‘Great Russia’ with ever-expanding borders. The toxic fantasy of this ‘Great Russia’, even if apparently endorsed by the Russian people, who are still suffering from the phantom pains of the lost empire, functions as an imaginary solution to their very real, lived misery under mafia-capitalism. Maidan, both as a concept and as the reality of a popular uprising, is what the Russian people actually need. Time and again.

Published originally in 2015

European Spectres and Ukrainian Bodies, or What is Maidan?

Olga Bryukhovetska

Recent years were marked by revolutionary uprisings in many parts of the world, but only in Ukraine was the main issue Europe. Of course, we have heard many times that this ‘Europe’ for which Ukrainian people are striving doesn’t exist. However, it is a mistake to see Ukrainian people as simply naïve and blind believers. Their message is much more sophisticated: ‘Europe’ doesn’t exist yet. It has not yet completed its way from abduction to Universal Human Rights. That’s why many prominent intellectuals claimed that the fate of Europe was played out on Maidan. So, what is Maidan?

The Ukrainian word maidan means ‘city square’, a concrete urban place rather than an abstract geometrical space, unlike its synonym ploshcha, literally ‘square’, which retains a double place/ space meaning. This place, maidan, is usually marked not only physically, as a geographical locale, but also as a place of social interaction, where individual, psychological subjects could bond into a collective, historical one. The diminutive form of the word can help to illuminate its social meaning: maidanchyk, a little maidan, means a playground and forms a part of a phrase referring to children’s playgrounds, places of initial communal experience and social bonding.

This is the linguistic meaning of the word maidan. What was the real Ukrainian Maidan? (I will use capital letters when referring to the event rather than the word.) Did it retain this double meaning of a geographical and social place? Wasn’t it a locale of a historical moment? Indeed, the most striking feature of Maidan was precisely this emergence of a collective, historical subject. But unlike the Orange Revolution nine years before, this subject was of a new kind. I wouldn’t dare to call it a ‘hybrid’, for it doesn’t have a head. It is headless, decapitated and decapitating. Maidan is not very unique in this sense. Like Occupy, it is a social movement which one can join but not lead. This type of social movement marks the transition from an authoritarian hierarchical structure of a party to a horizontal network of self-organizing people. The difference between Occupy and Maidan is not so much in the form but in the content. The Western version had difficulty articulating a clear goal which would bind people in common action and therefore ended up being rather sterile (at least to date). The common goal of Maidan was urgent and evident. But the type of community in Occupy and Maidan is almost identical, and both are part of a broader tendency of overcoming the Führerprinzip.

It is now time to introduce a Spectre that has long been waiting behind the door. ‘A Spectre of whom or what?’ we should ask before opening this door. The Spectre of Europe, a Europe that doesn’t exist (yet): becoming-itself-and-never-yet-being-there? Is there something else? When we think of Europe and Spectre, the first thing that comes to mind is, of course, a Spectre of Communism, with which Derrida established such an intimate Hamletian spiritual session right after its ‘collapse’. It is extremely enlightening today to reread not only The Communist Manifesto (1848) but also Derrida’s The Spectres of Marx (1993). One of the key questions of ‘hauntology’, established by this groundbreaking research, is related to a direction. Not a direction of where to go and how to get there, but of a direction from which a Spectre is coming to us. After the so-called collapse of Communism it becomes commonplace to say that while in Marx the Spectre of Communism comes from the future, now the direction has changed. Communism, the absolute utopian future, became its opposite, a torn-apart and traumatic dystopian past that always returns, that haunts the present with its repressed bloody visions. ‘There is no future.’ But did it ever exist before? And to take an opposite direction, wasn’t the Spectre described by Marx also coming from the past? Aren’t they all coming from that direction?

But the Spectre might as well be that of fascism. As Maidan has shown, Europe sometimes sees fascism everywhere but in its own eyes. One cannot deny that Europe was not only the birthplace of democracy, but that of fascism as well. And this Faustian ambivalence should be brought to light. The breakthrough of far right parties in European Parliamentary elections in 2014 recalls a famous aphorism, which I will cite in the form it is given in Theodor Adorno’s Minima Moralia (1951): ‘The splinter in your eye is the best magnifying glass.’4 It is particularly true for such a spectral subject as Ukraine.

Little is known in Europe about Ukraine. It is an obscure part of the ‘Bloodlands’, to use Timothy Snyder’s powerful geo-metaphor of the place between Berlin and Moscow, where in the twentieth century ‘Europe’s most murderous regimes did their most murderous work.’5 Europe is not even sure yet if Ukraine exists. And if it does, where should it be situated – outside or inside? Is it possible to be on both sides, both inside and outside? Lacan proposed a special term for such a case: ‘extimacy’.

The accusation of Maidan being fascist, which was widely promoted by Putin’s propaganda apparatus, was very misleading. Not to deny that there is a problem of fascism in Ukraine, as it exists virtually in every country of the world, no matter first, second or third. Nor to engage in (self-)victimization and claim immunity from such social illness. Fascists on Maidan were just a small, marginal, albeit highly toxic and embarrassing fraction. Maidan itself was not fascist. It was democratic, emancipatory and progressive.

Let Derrida’s Spectre play with the spectral part of the famous beginning of The Communist Manifesto and instead choose a different route, and pose another question: Do Spectres respect (national) borders? Or are they truly international beings? Do they act like nuclear clouds from Chernobyl that easily crossed the Iron Curtain and went through all of Europe (aside from France, as was famously proclaimed by the government of this hexagonal ‘Bermuda’)? But before we can even approach these questions we have to pause a short while on the borders themselves, the activity very well known for those who live between them. We might have just a very vague idea of the country we are about to enter, but we know very well when we cross its borders. Maybe that should be a definition of national identity, instead of some quality or essence. In this sense, the experience which Ukraine is undergoing exposes a truly traumatic dimension of the mutilation of the collective geo-body.

There are many other ways to approach the question ‘What is Maidan?’ One may even take an aesthetic stance and see it as an artwork, or rather an art process, not only because the barricades looked like contemporary art installations but more profoundly because Maidan was a process of (self-)creation of social, collective, communal body, of its shaping, sculpting, drawing, building, constructing, performing, living and working through.

The views and opinions published here mirror the principles of academic freedom and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of the L'Internationale confederation and its members.