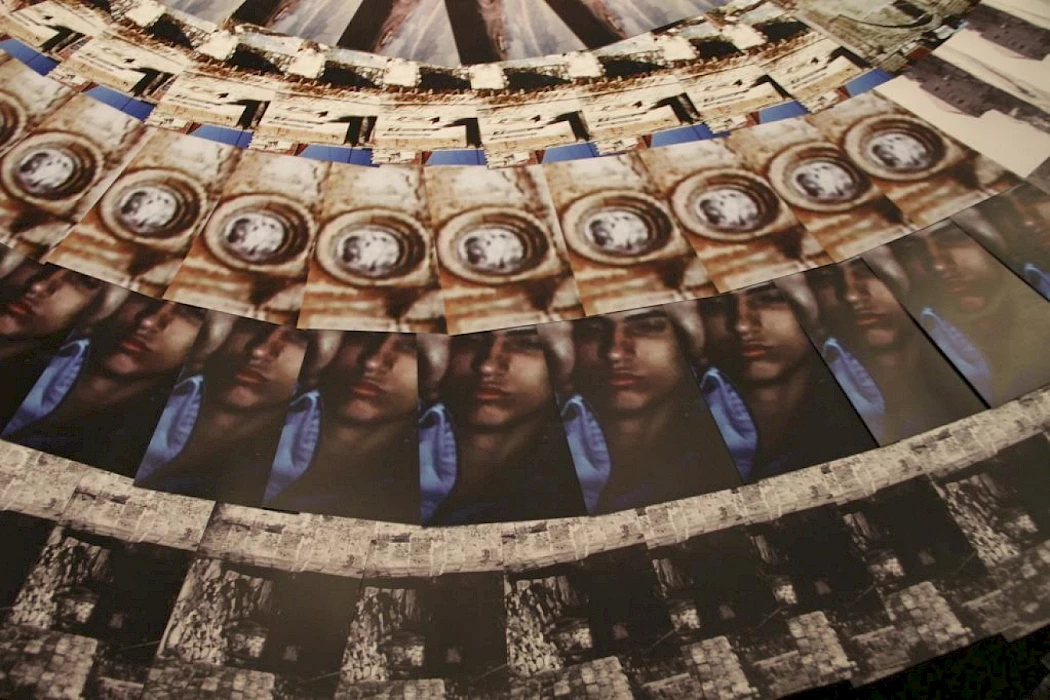

Kamal Aljafari, Not Without Me, Radcliffe Gallery, Harvard, 2010. Courtesy of the artist.

Kamal Aljafari, still from Port of Memory, 2009, 35mm, color, 58 min. Courtesy of the artist.

In the following article, I focus on contemporary artistic and research practices which challenge archives in colonial countries and zones of conflict. It continues my research on colonial archives in Israel or Israeli archives with colonial features, their characters and histories and concentrates on contemporary works by Israeli and Palestinian artists and researchers which re-read these colonial archives. I will demonstrate that the use of these colonial archives enables us to work against their original objectives, "against their grains" as defined by Ann Stoler (2002, p. 99), transforming them into sites of resistance.

Zionist colonialism in the land of Israel/Palestine began in the late nineteenth century and developed in various stages. In 1948 the Nakba launched the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinian population, the prevention of their return to their lands and homes, the occupation and Judaisation of Palestinian villages, towns and neighbourhoods. Subsequently, the Military Government (which was finally terminated in 1966) controlled the Palestinians who remained in Israel and exploited them economically. This continued during the War of 1967, with the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, which became increasingly violent, oppressive and exploitative as the years went by,1 and which involved the violation of human rights and dispossession of Palestinian lands for the benefit of Jewish settlements. Israel continues to systematically expand its direct control over the entire land, resources and population between the Mediterranean and the River Jordan while deliberately excluding the Palestinians by using a complex apparatus of oppressive mechanisms.

While one major aspect of the Zionist-Israeli colonial mechanism is physical, another involves the judicious and deliberate construction of a Zionist imagery system. From the earliest days of the Zionist movement, the colonisation of Palestine was described – often with the use of visual aids – in ethical, softened and euphemistic terms aligned with and constitutive of an official narrative. Discriminatory, immoral and oppressive mechanisms have been whitewashed ever since. Thus, for example, the propaganda departments of pre-Statehood institutions have instilled the narrative of "making the desert bloom", a desert supposedly empty of indigenous inhabitants, as well as the biblical ideology designed to establish the Jewish people's "historical right" to the land (Sela 2000). A prime example is the opening scene of Helmar Lerski's film Work (1935), in which the Zionist pioneer marches in a desolate and uninhabited landscape. Later on, the film describes his efforts to develop and inhabit the land, while biblical verses provide moral ground for colonisation. Erasing the pre-1948 Palestinian existence from the coloniser's mind or presenting it in a backward, "biblical" light, have laid the groundwork for the physical erasure and ethnical cleansing of the Palestinians in 1948 and thereafter.

Propaganda departments of pre-Statehood institutions gave birth to archives such as the Jewish National Fund and Keren Hayesod (United Israel Appeal), which now serve as evidence of the development of colonialism both in terms of their content and in terms of their structure (ibid). The Israeli authorities developed a sophisticated mechanism, aided by the War of 1967, that continued to structure the supposedly moral aspects of the occupation and the "historical right". Many civilian sectors – like the press, the crafts and cultural spheres – collaborated with this institutional mechanism which not only legitimised the occupation, but also sought to justify the settlement project which entered into high gear following the Arab-Israeli War of 1973 (Sela 2007).

Importantly, all the national archives in Israel – among them Israel State Archives, Central Zionist Archives, Jewish National Fund archive, Keren Hayesod archive and the various military archives– are but one component of a complex set of physical and discursive colonial mechanisms operating in such diverse areas as education, media, law, planning, and finance (Sela 2015).2 The effect of these mechanisms – which take part in human rights abuses, or in presenting them in a brighter or more positive light – on Palestinian and Israeli lives is destructive. Therefore, researching, exposing and criticising these mechanisms, as well as writing alternative narratives, are among the key duties of decolonial research and activism (Sela 2013).

In what follows, I focus on a limited number of examples of contemporary artistic and research activities that have a potential to write a history that subverts colonial-biased representations by using colonial archives in two ways. The first, to expose the colonial mechanism of the Israeli national archives, the second, their alternative readings. Thus the tendentious methods of colonial representation are revealed, their initial essence cracked and unofficial layers of knowledge are released. Such actions, I believe, undermine the archives' original purposes and contents and seek to unearth and decode repressed/ hidden contents (Sekula 2003; Sela 2013).

Not Without Me was an exhibition of work by Kamal Aljafari, a Palestinian filmmaker based in Berlin, at Radcliffe Gallery in Harvard in 2010. It presented postcards featuring images freeze-framed from Israeli and American films produced in Israel in the 1970s and 80s, in which Jaffa is used as an oriental setting. The movies themselves include no explicit reference to the city's Palestinian population – apart from "errors", i.e. shots in which Palestinians were captured inadvertently in the frame. Despite a Western, patronising point of view, these films are almost the last remaining documentation of neighbourhoods and buildings in Jaffa which have been destroyed and Judaised over the years by Israeli authorities. Therefore, these movies are – completely unintentionally – a source of significant historical information about the Palestinian characteristics of Jaffa which are consistently being erased by Israel and overwritten in the form of a gentrified and romanticised Tel Aviv suburb.3

In his 2009 film Port of Memory, Aljafari also embedded cuts from Kazablan (1973), an Israeli blockbuster originally documenting the struggle of Jews of Asian and African descent against the European-Jewish establishment. In those excerpts – which document the city's post-Nakba landscape – Aljafari planted actors and scenes that tell the story of Palestinian Jaffa, thereby creating a new narrative for the movie: the Palestinians' struggle against their evacuation, the destruction of the Old City and ongoing municipal neglecting. As Aljafari stated: "The Israelis expropriated not only our homes and lands, but also our struggle. I therefore re-appropriate cuts from the movie in order to restitute the city, its history and its identity to the Palestinian population" (Sela 2013, p. 243).

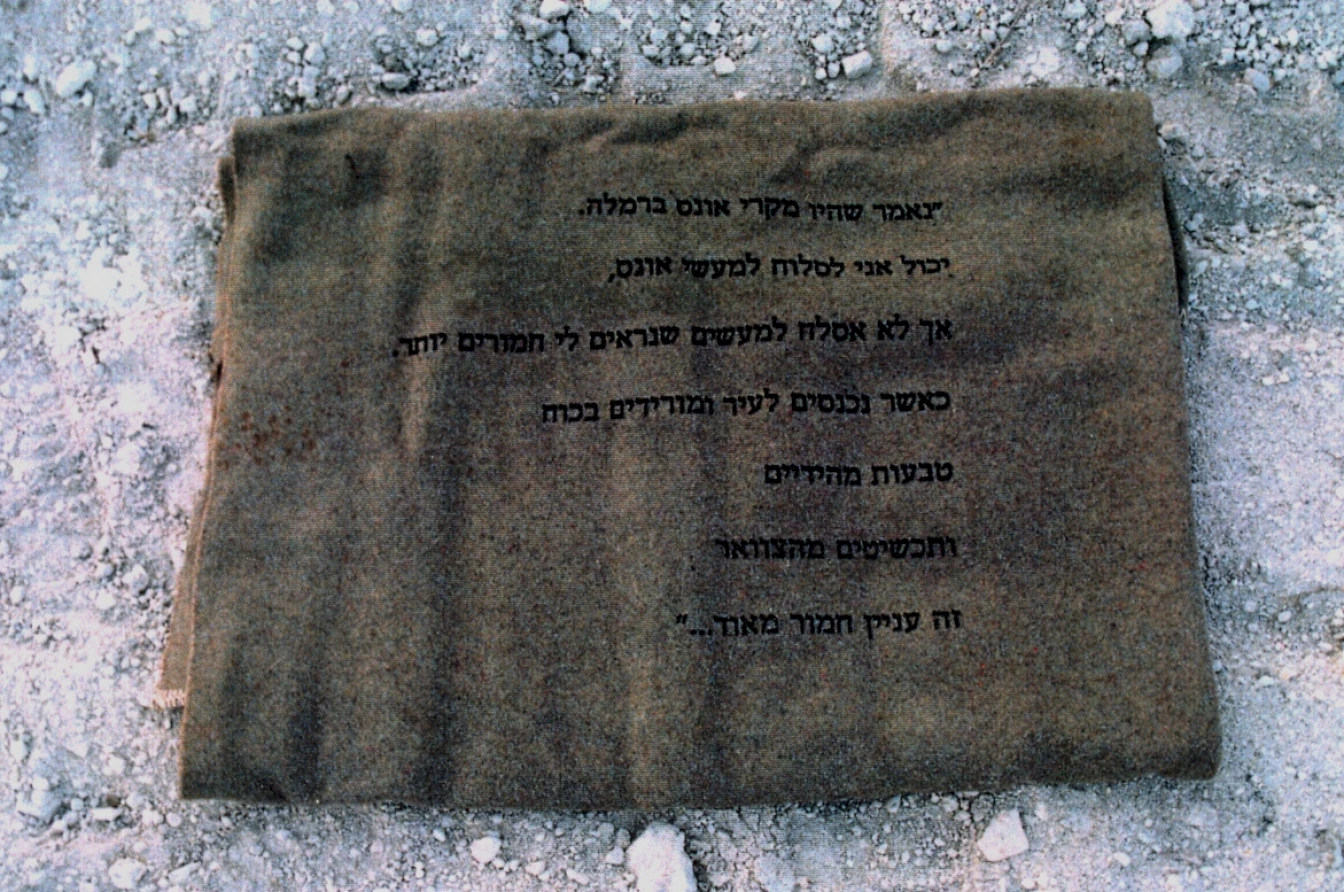

Israeli artist Meir Gal's series Untitled (1994) deals with cases of looting, rape and unlawful killing in 1948 as documented in official Israeli archives. Gal used Israel Defense Forces' issued blankets – objects strongly connoted with the Israeli military experience – on which he printed minutes from the Israeli government discussions concerning these cases. One of the works in the series, Tales of Rape and Worse, includes quotes by Aaron Ziesling, the Minister of Agriculture in the first Israeli government: "They say there were cases of rape in [recently occupied] Al-Ramlah. I can forgive acts of rape, but I will not forgive acts that seem more serious to me. When [soldiers] enter a city and take rings off fingers and jewelry off necks – that's a very serious matter"4 (Segev 1984, p. 85; Sela 2013). This work was made possible thanks to the efforts of Israel's so-called New Historians who have been exposing, since the late 1980s, previously unused materials in official Zionist historiography. Forty years after the establishment of the State of Israel, historians began accessing materials that had been restricted in the national archives, allowing them to write alternative histories.5

Another project which sought to challenge the official Israeli archival materials is a project I worked on called Haifa: 1948–2013 (Sela 2013, pp. 243–244). This was based on the research materials used by "official" historian Tamir Goren for his book Arab Haifa in 1948 published in 2006. I presented the documents that he collected but were not eventually included in this book. Goren's book, written from a Zionist perspective, largely avoids any issues that are inconsistent with the official national narrative, such as acts of aggression towards Palestinian civilians, massive dismissals of Palestinian workers, looting, refusal to let families reunite, or Jews who squatted in Palestinian homes. These findings, which were collected by him in his research but not exposed, were presented in Haifa: 1948–2013. For example, Mr. Shehade complains in a letter to the Director of the Department of Minorities in Haifa that during his sister's absence: "Ms. Hoffman Anna and Ms. Rosner Barina squatted in her apartment without receiving permission from me or from any authority, and since they have refused to vacate the apartment I contacted the Jewish Agency in Haifa... but unfortunately... those two ladies told me they would not leave the apartment".6 This project exposes just a few of the countless letters written by members of the Palestinian Nakba generation who remained in the country and had to cope with the impossible conditions imposed by the new Israeli rulers. Stored in official archives, these letters were mostly written by Hebrew-speaking lawyers on their behalf, and accordingly their tone is apologetic if not subservient. Beyond this facade, however, the letters – now exposed to the public for the first time – clearly voice the tremendous hardships and insults experienced by the Nakba generation. They also provide detailed information about the looted property, ethnic cleansing and more – information that is essential for the future writing of Palestinian history.

Meir Gal, Untitled (Tales of Rape and Tales Far Worse), 1994. In Hebrew: "It has been said there were acts of rape in Ramleh. I can forgive acts of rape, but I cannot forgive acts that appear to me more severe. When entering [soldiers] a city and removing a ring from a hand and jewelry from a neck. That is a very serious matter". Silkscreen on military blankets. Courtesy of the artist.

Meir Gal, Untitled, 1994, silkscreen on military blankets, sand and bulbs. Installation shot, Fawaran (Unrest) – Housing, Language, History – A New Generation in Jewish-Arab Cities, Nachum Gutman Museum of Art, Tel Aviv, April–August 2013, curator: Rona Sela. Courtesy of the artist.

In 2009, following the exhibition Made Public – Palestinian Photographs in Military Archives in Israel at Minshar Gallery in Tel Aviv and the publication of the accompanying book (Sela 2009), I presented at Pecha-Kucha Jerusalem a series of aerial photographs, taken by pre-State Jewish military forces, of Palestinian villages and towns from this project. Taken by the Palmach Squadron as intelligence gathering for surveillance, control and occupation purposes, from 1946 to early 1948, these photographs were accompanied by extensive textual surveys and photographs ("village files") of Palestinian villages and towns collected by Jewish scouts on the ground for the same targets. They were declassified (open) in the military archives in Israel during the last decade. In the event I claimed that these images and surveys, can today change their colonial functionality and original targets and expose the Palestinian geographical deployment that Israel ruined in 1948 and after. They are, therefore, the last evidence of the Palestinian entity before the Nakba. A member of the audience asked whether I was not afraid that these hundreds of aerial photographs would be classified (close) again, as a result of my research that exposed them in a subversive manner in the public sphere. People laughed, but eventually this is what happened. The photographs were classified again.

Despite the "archive guards" who continue to control the official representation of the archives and the way they are loaded by meaning, the control over the history of the oppressed enables, in an unexpected manner, the emergence of new forms of archival resistance. While these "archive guards" control the various "stages of production" of meaning and strengthen their domination over the process of knowledge production; new creative and marginalised ways to define the boundaries of the archives and free them from biased contents are created by artists and researchers, consolidating the archive's role as a site of resistance.

Translated from Hebrew by Ami Asher

References:

Goren, T. 2006, The Fall of Arab Haifa in 1948, The Ben-Gurion Research Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Press, MOD Publishing House, Haganah Historical Archives (in Hebrew).

Segev, T. 1984, 1949: The First Israelis. Domino, Tel Aviv (in Hebrew).

Sekula, A. 2003, "Reading an Archive: Photography between Labour and Capital," in L. Wells (ed.), The Photography Reader, Routledge, London and New York.

Sela, R. 2000, Photography in Palestine in 1930s&1940s, Hakibutz Hameuchad Publishing House and Herzliya Museum (in Hebrew). For information in English, see: ronasela.com.

Sela, R. 2007, Six Days plus Forty Years, Petach Tikva Museum of Art, Israel (in Hebrew).

Sela, R. 2009, Made Public – Palestinian Photographs in Military Archives in Israel, Minshar for Art, Israel, (in Hebrew). For information in English see here.

Sela, R. 2013, "Embroidering the Change – Art, Activism and Change in Bi-National Cities in Israel since 2000", in R. Sela (ed.), Fawaran (Unrest) – Housing, Language, History – A New Generation in Jewish-Arab Cities, Nachum Gutman Museum of Art, Tel-Aviv. (in Hebrew and Arabic). For information in English see here.

Sela, R. 2015, "Rethinking National Archives in Colonial Countries and Zones of Conflict", in A. Downey (ed.), Dissonant Archives: Contemporary Visual Culture and Contested Narratives in the Middle East, I.B. Tauris, London.

Stoler, A. L. 2002. "Colonial Archives and the Arts of Governance". Archival Science 2.