Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Through text, image and sound, writer and photographer Katia Golovko reflects on her dialogue with the termite mounds of Northern Senegal. The mounds, which she first encountered in 2021 ago, have become a site to meet the limits of her own subjectivity as well as showing more-than-human models of being together. The accompanying sound piece is by Cristian Adamo and is intended to be listened to whilst reading. The contribution is part of the ongoing publication project … and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world, edited by Martin Pogačar.

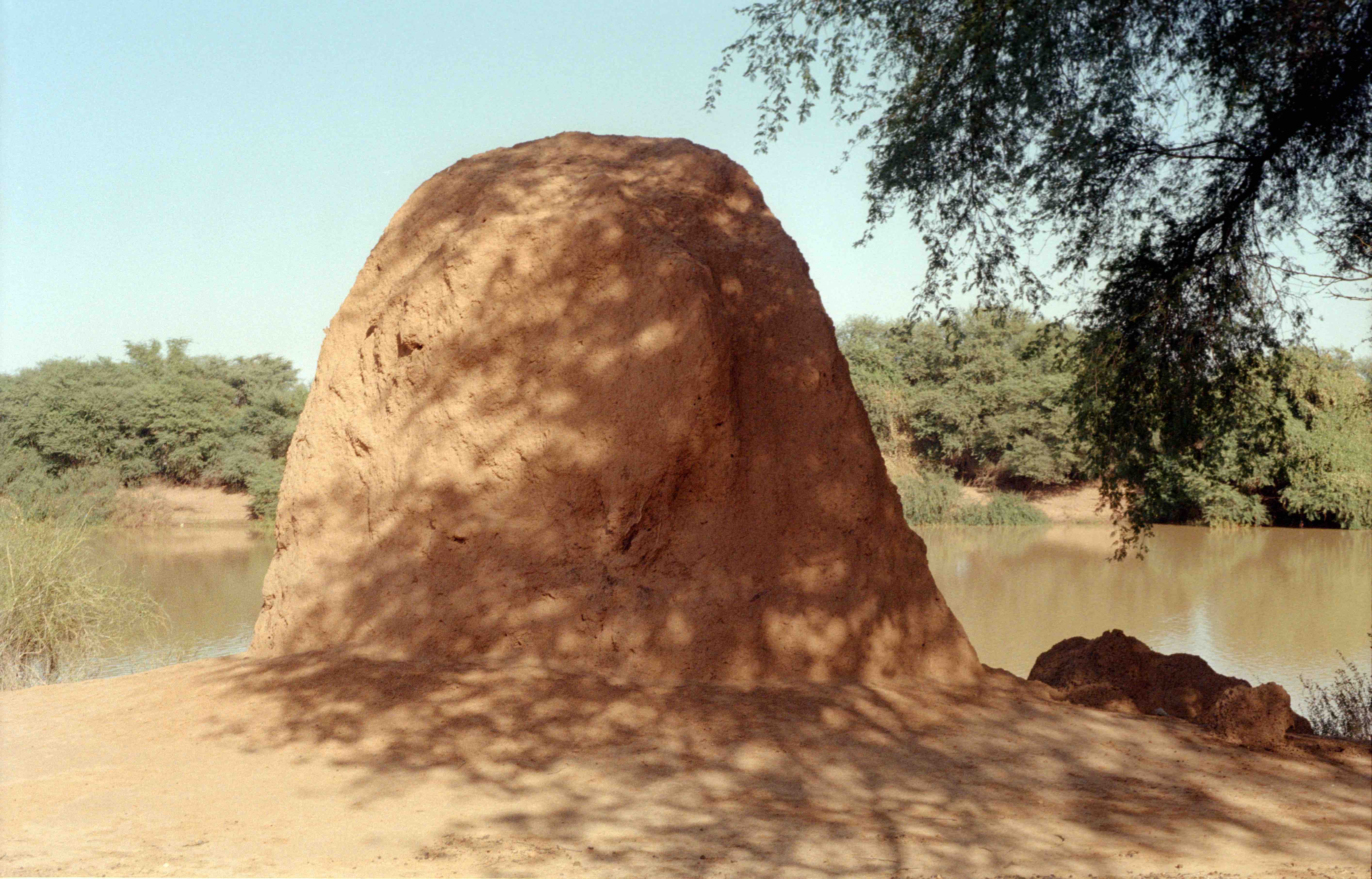

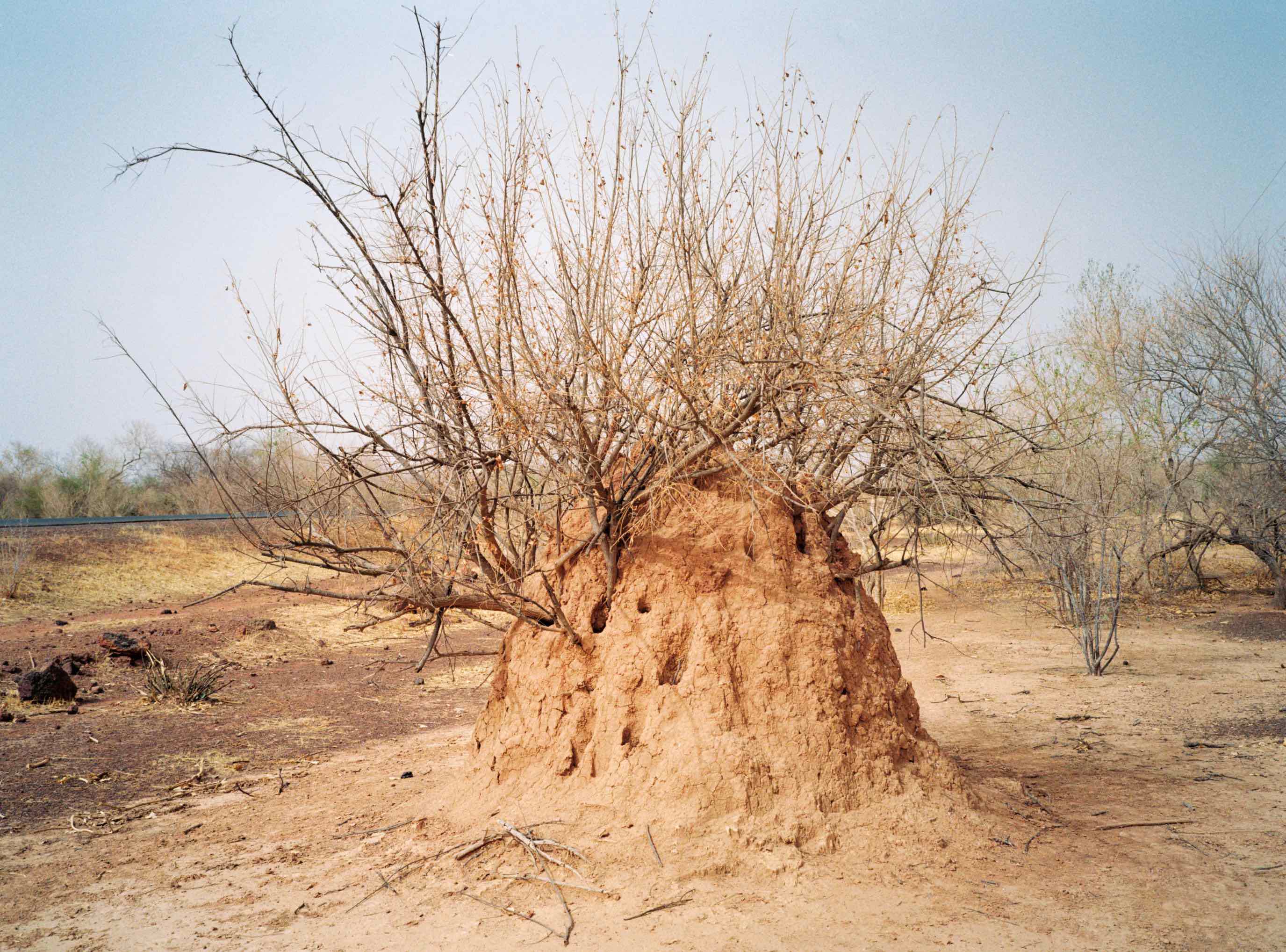

In December 2021, together with a group of friends, I was on the largest island in Senegal. Situated between the Senegal river and its tributary, Doué, it is known by the French name ‘Île à Morphil’, literally meaning ‘Ivory Island’, a reminder that elephants used to live here until the 1960s before they became extinct due to hunting. Today, only the name remains. We had come to see the small eighteenth-century mosques scattered around the island, though we spent more time driving between villages than visiting them. Île à Morphil is a realm of trees and termite mounds, birds and palm rats, strolling goats and rare passersby appearing from behind the trees and disappearing as unexpectedly as they appeared.

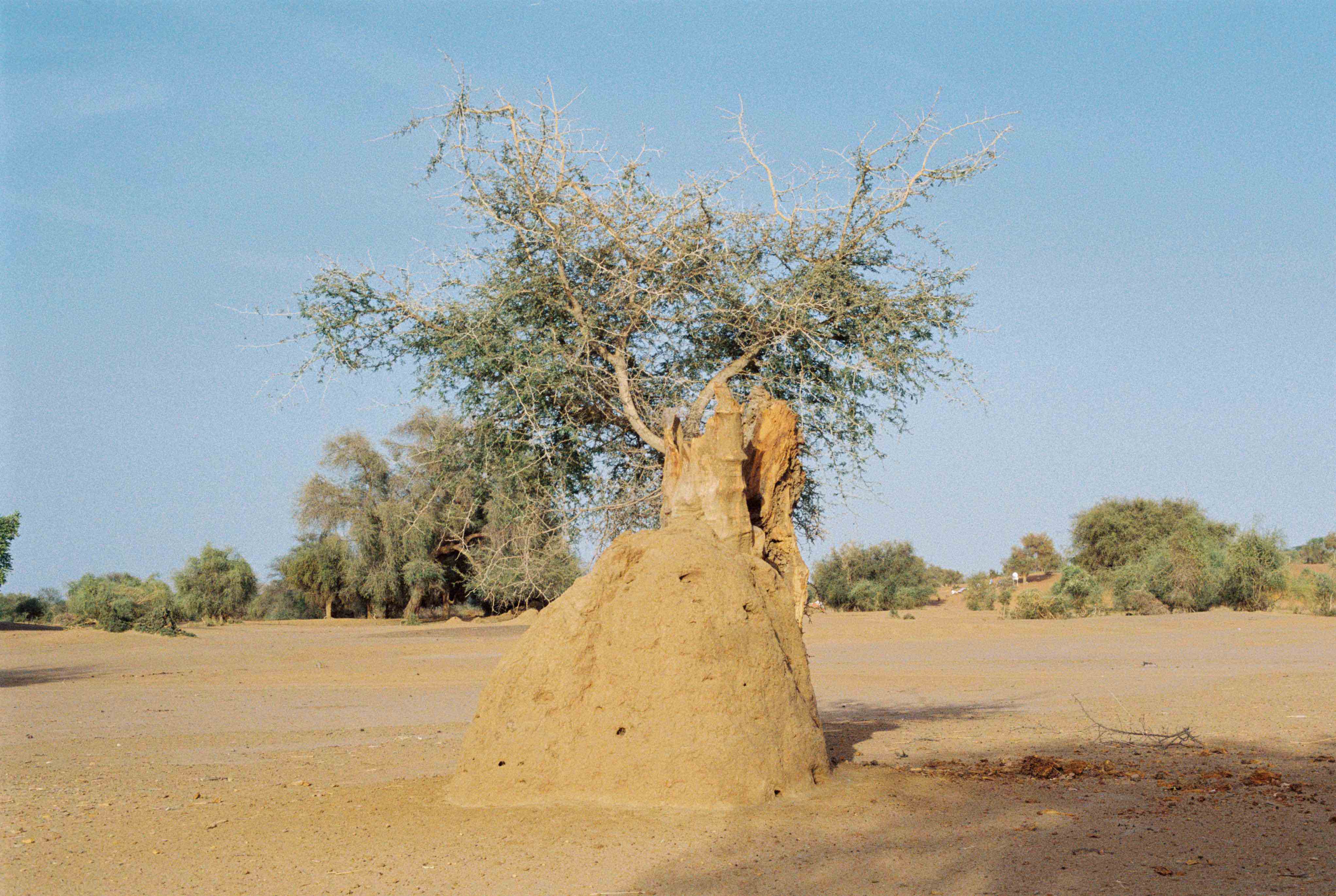

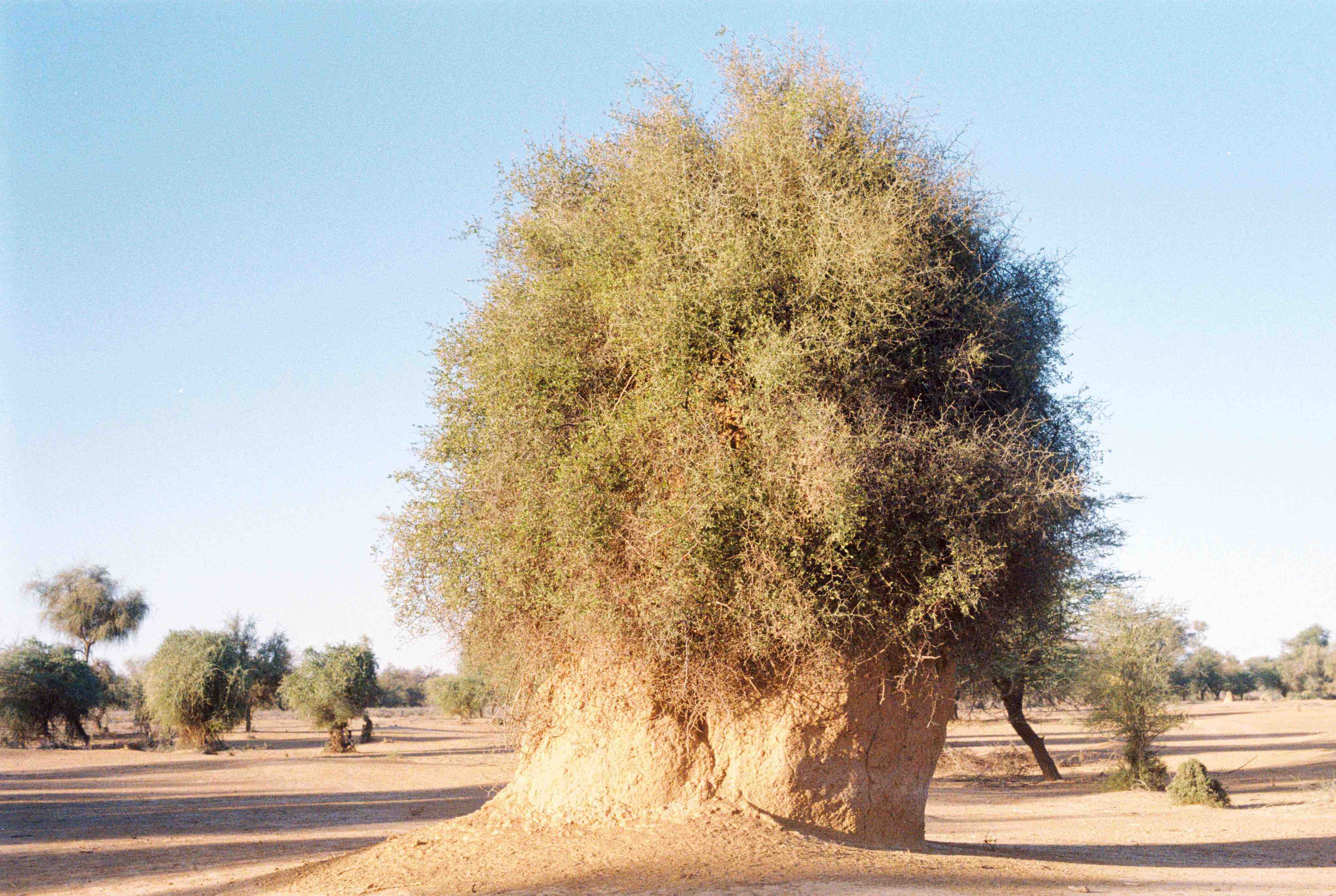

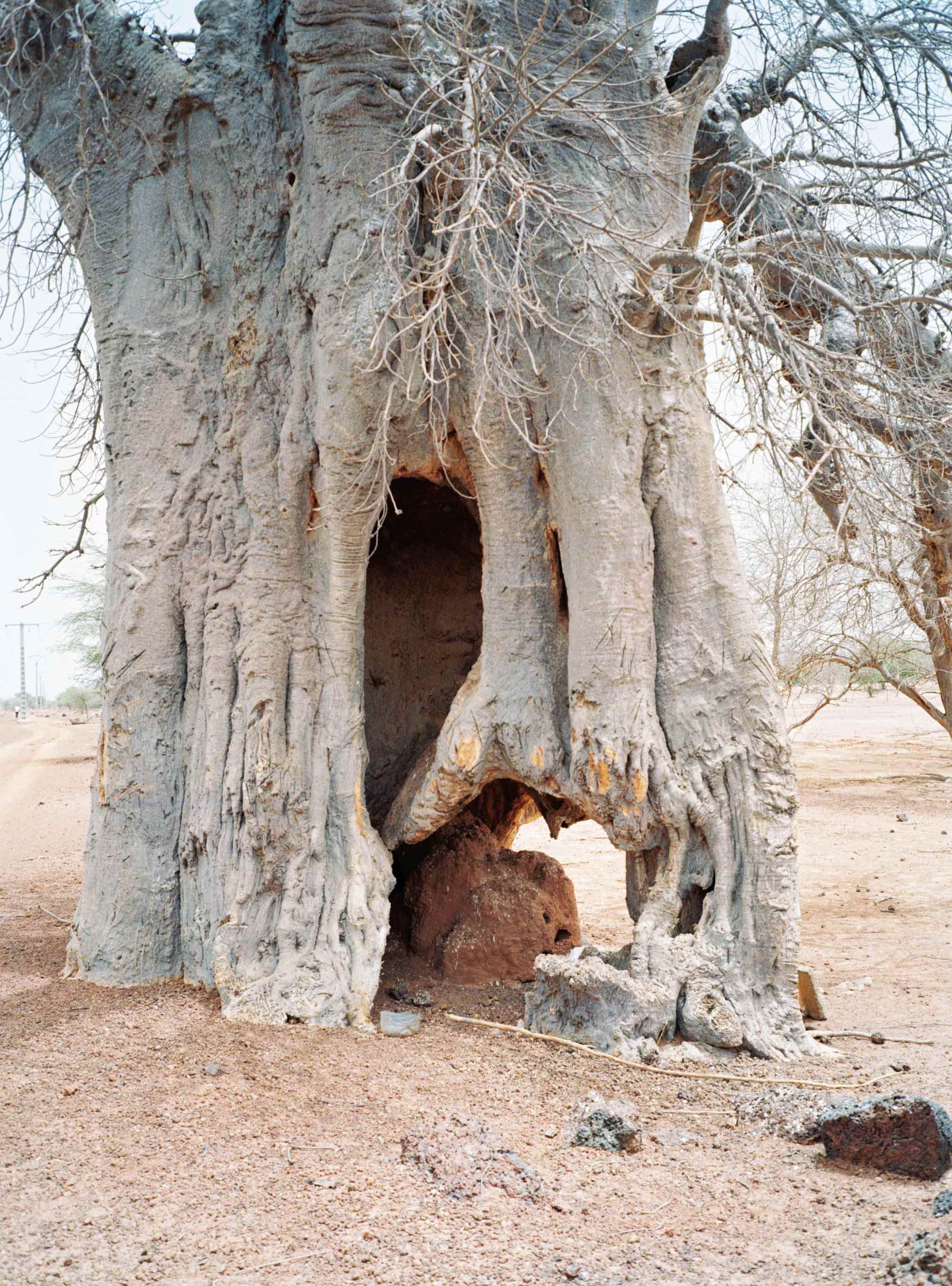

At some point, while driving, we stopped next to a giant tree-shaped shrub–termite mound: the trunk is the termite mound and the crown is the tree canopy. It is not possible to say how one is entangled with the other; they constitute a single whole, a world created by the coexistence of at least two living beings. These two are those that are visible, but many more remain inaccessible to the human eye.

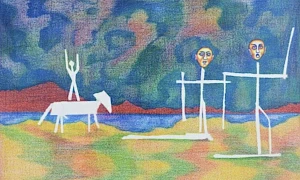

During this first encounter with the termite mound, I reached for my camera but the roll ran out after two shots. This is the picture I took:

Philosopher David Abram writes that ‘nonhuman nature can be perceived and experienced with far more intensity and nuance than is generally acknowledged in the West’.1 That first encounter with the termite mound felt like an unexpected meeting that confronted me with the limitations of my visual, subjective experience, taking me to a ‘place’ that modern, urban culture had taught me to unlearn. Over the course of my research, the termite mound has come to offer me a new way of understanding my own subjectivity. At the same time, as a physical, highly situated living form, it has allowed me to contemplate alternative modes of being to those of capitalist extractivism and the ruins it continues to leave in its wake.

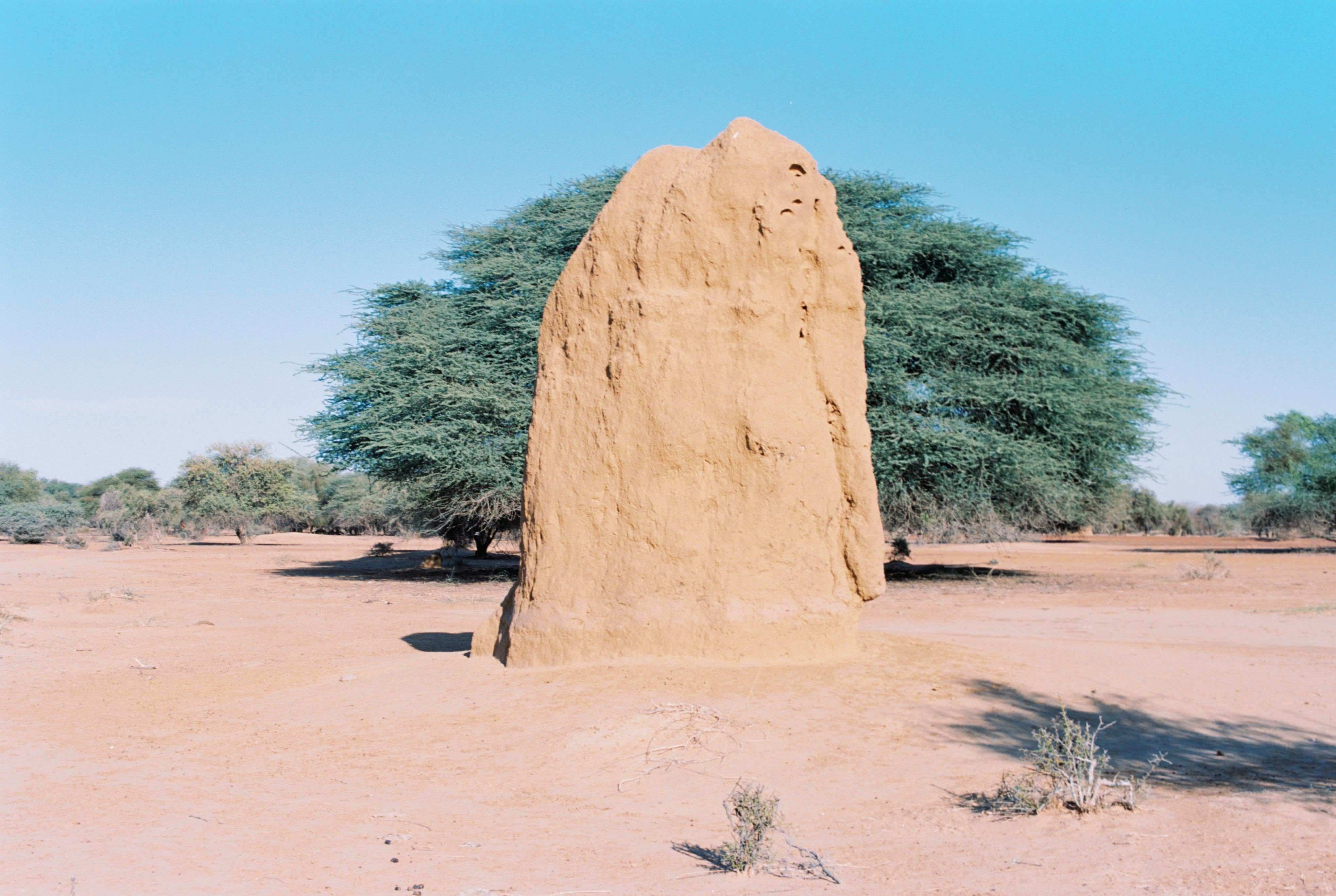

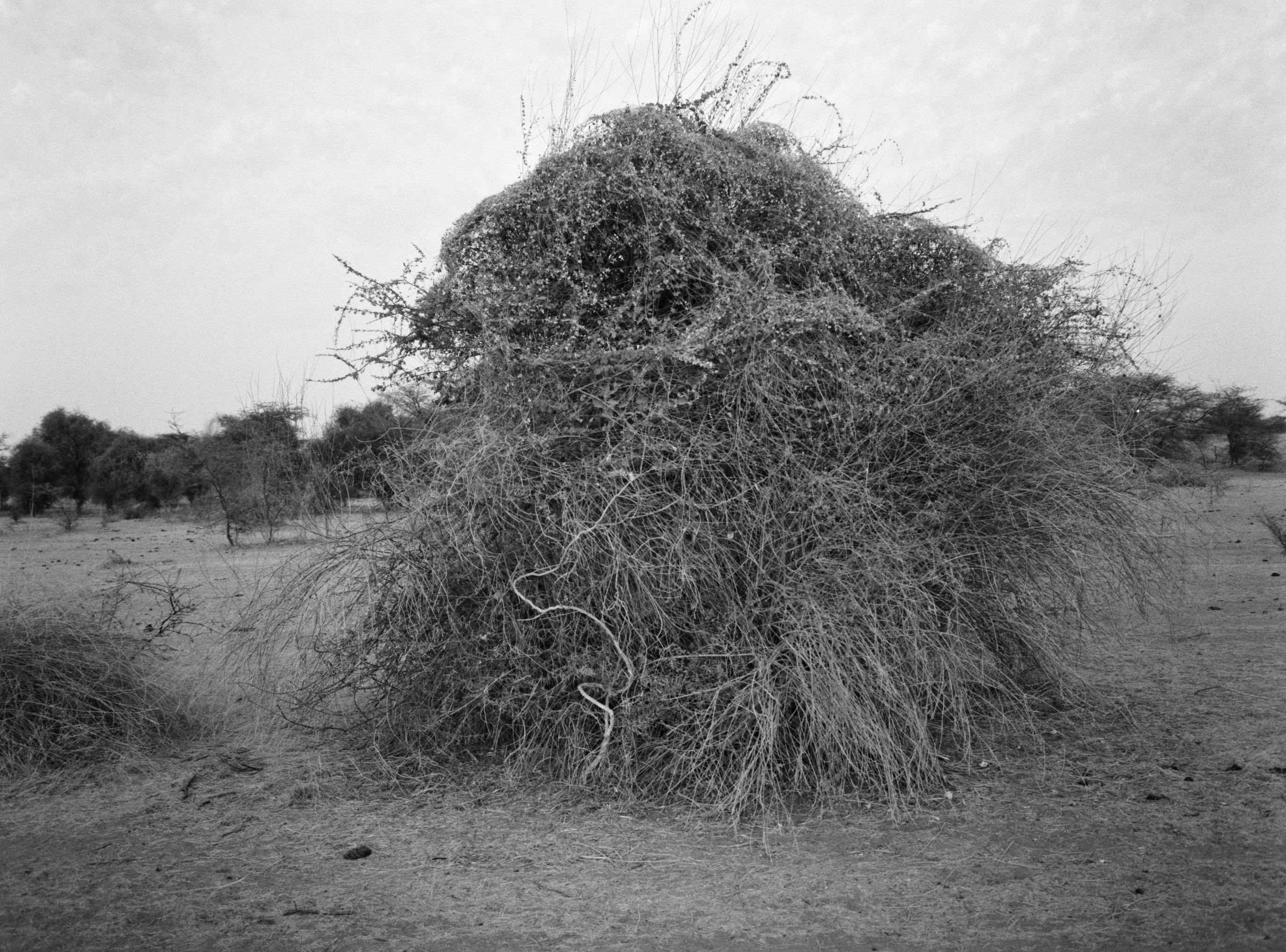

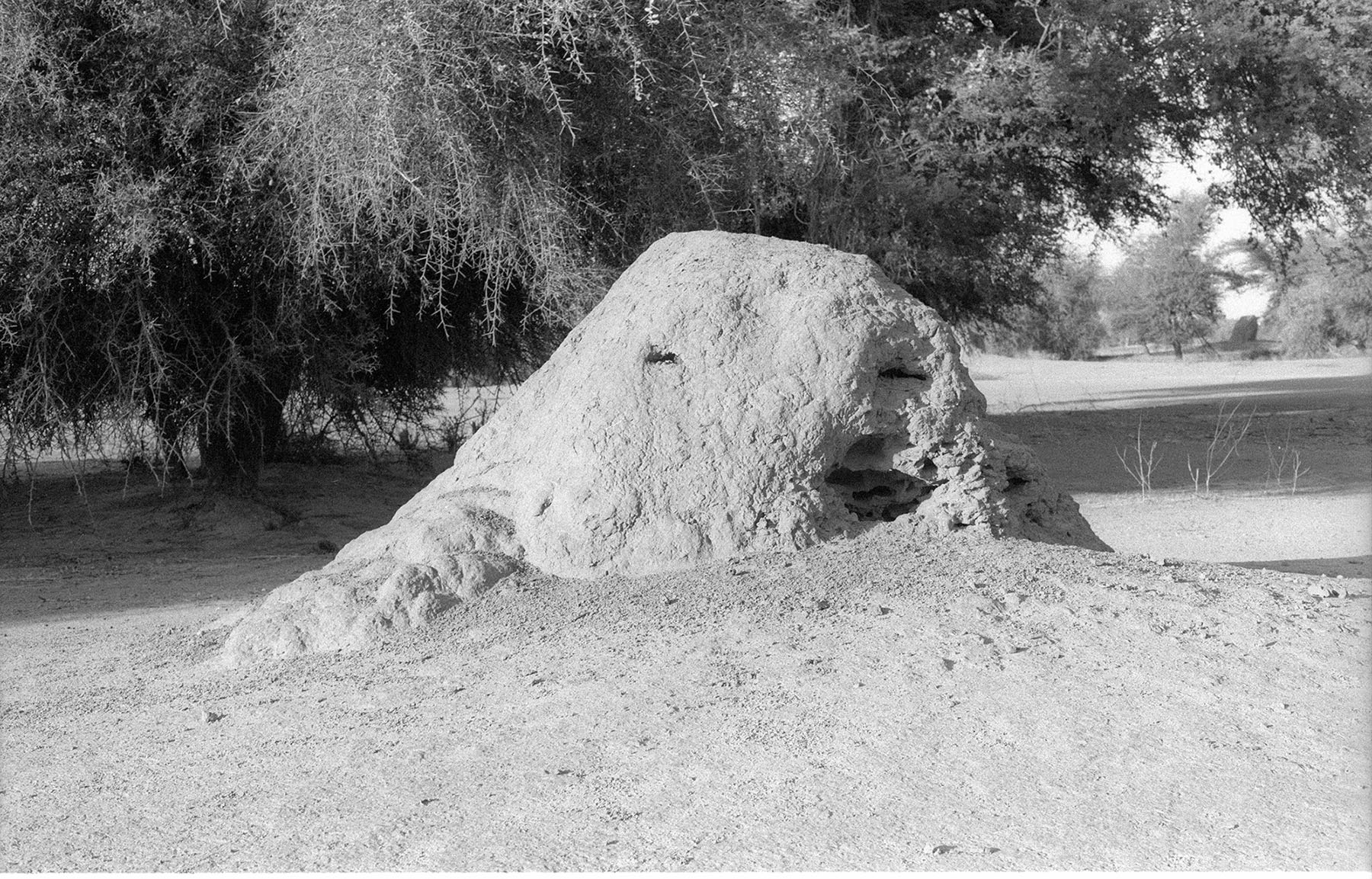

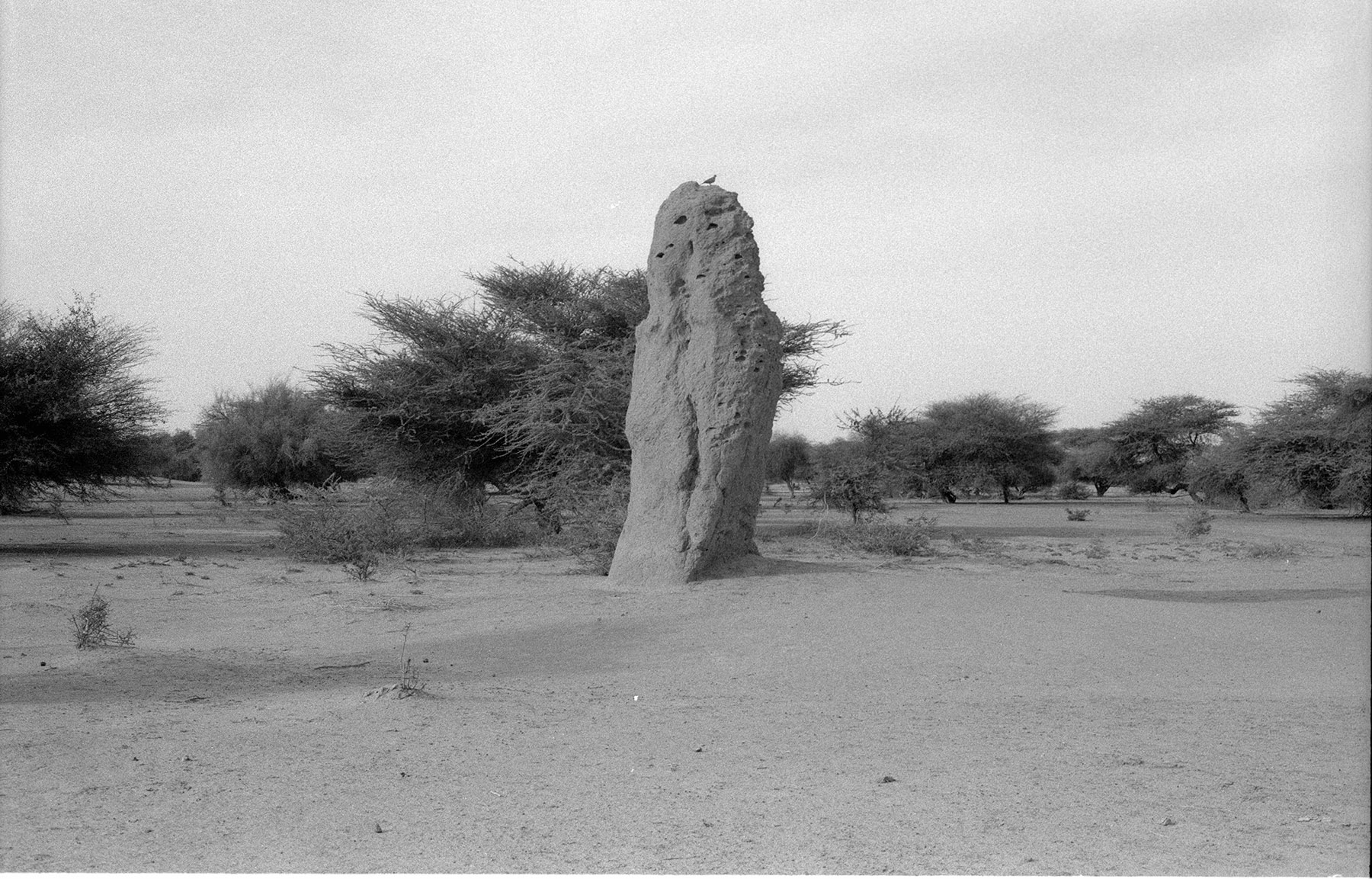

Since that first meeting, I have returned regularly to this particular mound and the surrounding area, taking photographs with an analogue camera. The process of analogue photography delays the moment of seeing the image. Once I see it, I am closer to the moment I took the picture, but also elsewhere, in another time. Analogue photography disrupts linear, temporal experience by making past moments visible. The photograph, as light etched on film, reconfigures presence and absence, duration and fugitivity. Brief moments spent in places can be represented by images – photographs – that crystallize those moments forever. Or, the long time we spend in places can be condensed into a single shot taken in fragments of a second. A still image is only a detail of what is felt, sensed and seen. It is inherently incomplete and fragmentary. The mounds are fixed, static formations that change over time, but these changes might not be visible to the camera, even over the course of weeks or months. This peculiarity of termite mounds, their apparent stability and internal dynamism, makes them generative, if perhaps counter-intuitive, subjects for photography.

As journalist Lisa Margonelli writes, ‘to really “see” the termites we have to step out of the rules of being human. Speed up time and you can see that the ground beneath us is moving as many billions of tiny termite feet carry tiny grains of dirt.’2 Standing next to many mounds, I try to feel the presence of millions of termites, of their movements that happen underground and around me.

I return to a quote from W.G. Sebald’s novel Austerlitz (2001):

It does not seem to me, Austerlitz added, that we understand the laws governing the return of the past, but I feel more and more as if time did not exist at all, only various spaces interlocking according to the rules of a higher form of stereometry, between which the living and the dead can move back and forth as they like, and the longer I think about it the more it seems to me that we who are still alive are unreal in the eyes of the dead, that only occasionally, in certain lights and atmospheric conditions, do we appear in their field of vision.3

Dénètem Touam Bona writes about marronage as a form of nomadism:

Even when a maroon community remains in the same place for a long time, it remains nomadic, in other words stealthy, because of its capacity to escape the gaze and the grasp of external forces. Cultivating invisibility is a question of life or death when one is faced with far more numerous and much better armed enemies.4

Mounds are often enormous structures visible from afar, but termites are never visible, especially under the sun that is deadly for them. They create their own space, preserving invisibility in order to survive. They create spaces of escape from sunlight, heat, predators, other insects and particular enemies – ants, as well as others. When I think of their life practices, my mind turns to those of others that build their lives as a form of escape.5

There are numerous examples of writers, artists and researchers exploring alternatives to the pervasive violence of capitalism, through encounters with the more-than-human world: Ursula K. Le Guin via her carrier bag, Tiffany Lethabo King with her shoals, with lichens for Laurie A. Palmer, with lianas for Dénètem Touam Bona,6 with moss and plants for Robin Wall Kimmerer, and many others. Le Guin speaks of the carrier bag as, variously, a medicine bundle, a ‘vast sack, the belly of the universe, this womb of things to be and tomb of things that were, this unending story.’7 King speaks of shoals as spaces of possibility, of epistemological aperture, of methodological freedom. In The Black Shoals (2019), she refers to the shoal as a geographical formation between water and land, a geologic formation that is neither fully land nor sea. King employs the shoal as a powerful metaphor and methodological tool to explore the complex and often contentious interactions between Black studies and Native studies.8 Sketching out a chiaroscuro philosophy of the bodies, social practices and rituals that have historically embodied resistance to racial capitalism, Bona focuses on lianas, on human and nonhuman populations, and on the landscapes and narratives they conjure up in our imaginations. For him, the liana gives rise to subversive architectures, other ways of thinking, creating and fighting together. As a link and metaphorical lever, it also becomes an opportunity to reflect on the possibility of alliances, of a ‘liannaj’ between different experiences of minority and domination.9 For me as well, as I started learning about mounds, termites, the fungi inside, their forms of coexistence and symbiosis, they became a virtual portal, a methodological and visual tool and an epistemological space.

In The Soul of the White Ant (1937), really the classic book on termites, Eugène Marais describes them as a ‘composite animal’ that unites the workers, the soldiers, the queen and the king within the mud structure of the mound as a single body.10 Since then, the term ‘superorganism’ has come to be used most often to describe social units of eusocial animals in which division of labour is highly specialized and individuals cannot survive by themselves for extended periods – and scientists consider the termite colony to be one. A superorganism can either be a group of synergistically interactive organisms of the same species or a more diverse group of living things (in this case termites (and all of their castes) and fungi) that function synergistically in a space (the mound) to work towards a collective goal. Termite workers and soldiers are unable to reproduce; soldiers and kings cannot feed themselves, workers and kings generally cannot defend themselves adequately, soldiers and workers cannot fly out of the nest.11 As Margonelli writes:

If the termite mound is a composite animal composed of millions of self-organizing termites, the termite itself is another shell company for a consortium of five hundred species of symbiotic microbes, all cooperating to digest wood for the mutual benefit of the Many.12

The survival of termites is not possible without the fungi they cultivate, so they create and maintain the microclimate necessary for their existence. But, too, the fungi cultivate termites, because they could not survive without the care that termites bring.13 For Marais, the termite mound has a sort of group soul, that of a composite animal, ‘a separate and perfect animal, which lacks only the power of moving from place to place’.14

Kimmerer writes about the ‘web of reciprocity’ as a principle of existence where each living being has a particular role to play.15 The termite mound is a universe of cohabitation, a space of connection between sun, soil, plants and air. It is a complex system of relations, webs of reciprocity among living beings enacting different ways of living together that connect, protect and help, sharing space and nutrients. The mounds’ extraordinary protective architecture has inspired Sahelian mud architecture by humans.

Termites, as a superorganism, reject the idea and practice of individual-ism. Etymologically, ‘individual’ comes from the Latin ‘individuus’, a word composed of the privative prefix ‘in-’ and ‘dividuus’, ‘divided’. It is the lemma corresponding to the Latin translation, first made by Cicero, of the Greek word ‘ἄτομος’, composed of the privative ‘ἀ-’ and the motive ‘τέμνω’, ‘to cut’. Thus, ‘individual’ means ‘indivisible’; in philosophy, along with ‘individuum’, it is used to indicate that each (individual) being has characteristics that make it unique.16 As Bona writes, the individuum is a unit of capitalist rationality. It’s a deliberate confinement of (human) being and its extraction from its environment, surroundings, memories.17 Édouard Glissant distinguishes between a rhizomatic and a single-rooted notion of identity, identifying a Western cultural insistence that identity is unique and exclusive of the other.18 Instead, Glissant understands the formation of identity as a result of creolization, as rhizome – a root meeting other roots. He asks: ‘How to be oneself without closing oneself to the other, and how to open oneself to the other without losing oneself?’19

The lives of termite mounds are statements of dependence between countless organisms and interconnections. The mounds offer a means to think through multiplicity, beyond the conceptual exclusivity of the ‘single-rooted’ individual form. Moreover, they model how to build non-extractive relations: engaging in and with the world as a web of reciprocity, living as part of a superorganism, interacting and interconnecting at all stages of life.

All photographs were taken by Katia Golovko in the departments of Podor, Dagana, Louga and Linguere in Senegal between January 2022 - December 2024.

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production

The Studies Center of Museo Reina Sofía will publish an open call for four residencies of artistic practice for projects that address the emergencies and challenges derived from the climate crisis such as food sovereignty, architecture and sustainability, communal practices, diasporas and exiles or ecological and political sustainability, among others.

-

–tranzit.ro

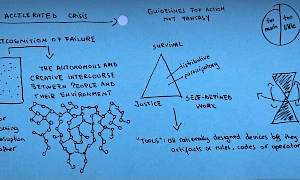

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

–M HKA

The Lives of Animals

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at M HKA that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ is a series of sound installations by Özcan Ertek, Fulya Uçanok, Ömer Sarıgedik, Zeynep Ayşe Hatipoğlu, and Passepartout Duo, presented at Salt in Istanbul.

-

–SALT

Sound of Green

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ at Salt in Istanbul begins on 5 June, World Environment Day, with Özcan Ertek’s installation ‘Sound of Green’.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Open Call: Research Residencies

The Centro de Estudios of Museo Reina Sofía releases its open call for research residencies as part of the climate thread within the Museum of the Commons programme.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

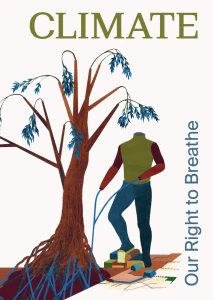

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organisations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

–SALT

The Lives of Animals, Salt Beyoğlu

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at Salt that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Plant(ing) Entanglements

The series of sound installations Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them ends with Fulya Uçanok’s sound installation Plant(ing) Entanglements.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production. Research Residencies

The projects selected in the first call of the Sustainable Art Practice research residencies are A hores d'ara. Experiences and memory of the defense of the Huerta valenciana through its archive by the group of researchers Anaïs Florin, Natalia Castellano and Alba Herrero; and Fundamental Errors by the filmmaker and architect Mauricio Freyre.

Related contributions and publications

-

Eating clay is not an eating disorder

Zayaan KhanThe Climate ForumRecette. Reset. Recipes in and Beyond the InstitutionClimatePast in the Present -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna Zielińska... and the Earth alongClimate -

Indra's Web

Vandana Singh... and the Earth alongPast in the PresentClimateZRC SAZU -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin Pogačar... and the Earth alongClimatePast in the Present -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloThe Soils ProjectClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoThe Climate ForumClimateHDK-ValandEN es -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

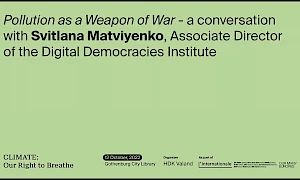

Pollution as a Weapon of War

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimate -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

ClimateThe Climate Forum -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosThe Climate ForumClimate -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifThe Climate ForumClimate -

Pollution as a Weapon of War – a conversation with Svitlana Matviyenko

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

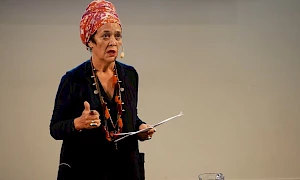

Françoise Vergès – Breathing: A Revolutionary Act

Françoise VergèsClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Ana Teixeira Pinto – Fire and Fuel: Energy and Chronopolitical Allegory

Ana Teixeira PintoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Watery Histories – a conversation between artists Katarina Pirak Sikku and Léuli Eshrāghi

Léuli Eshrāghi, Katarina Pirak SikkuClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

One Day, Freedom Will Be

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoTowards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyInstitute of Radical ImaginationClimate -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoInstitute of Radical ImaginationClimate -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: The Arrow of Time

Catherine MorlandClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoInstitute of Radical ImaginationClimate -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoInstitute of Radical ImaginationClimate -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterThe Climate ForumClimatePast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nkule Mabaso, Nick AikensThe Climate ForumClimateHDK-Valand -

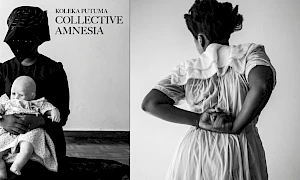

Graduation

Koleka PutumaThe Climate ForumClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaThe Climate ForumClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideThe Climate ForumClimate -

Soils

The Soils ProjectClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoThe Climate ForumClimate -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanTowards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the PresentClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezThe Climate ForumClimate -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaClimateM HKA -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia Golovko... and the Earth alongClimate