Chile: Shattering the Neoliberal Spell Joy and Desire Against Economic Obedience

John Dugger, Chile Vencerá, Trafalgar Square, London, 1974.

A work dedicated to joy is not apolitical because it wants to make people feel the urgency of the present, which is the urgency of revolution.

–Cecilia Vicuña1

The social unrest that flared up in Chile in October 2019 severely rattled the social and economic frameworks that were developed in Latin America during the previous decade. The election of right-wing governments in countries such as Argentina (Mauricio Macri in 2015), Peru (Pedro Pablo Kuczynski in 2016), Honduras (Juan Orlando Hernández in 2017), Chile (Sebastián Piñera in 2017), Colombia (Iván Duque in 2018), and Brazil (Jair Bolsonaro in 2018), and the overthrow of democratically elected governments by parliamentary coups in Honduras (2009), Paraguay (2012), and Brazil (2016), signaled the ebb of the ‘Pink Tide’ and the return of the neoliberal model accompanied by ultraconservative views and religious discourse. As the bewitching promise of neoliberalism has spread, however, it has been met with fierce resistance in some places; the recent uprising in Chile sent a powerful social, creative, and artistic message to the rest of Latin America.

For many years, neoliberalism’s champions have pointed to Chile’s apparent financial growth as proof that true societal improvement can only be achieved by a free market economy, lowered public expenditures, and State support of the private sector. But that false narrative of a calm, prosperous nation began to fall apart on October 14, 2019, in Santiago, when hundreds of students balked at the new metro fare, which had been increased by 30 pesos (US$ 0.03) five days earlier. Public outrage erupted in a country where wages are among the lowest in the region, and the cost of food, medicine, and education is among the highest. Over the course of the next few days the turmoil escalated and led to street battles with the police, looting, arson, and riots. On October 20 a frightened president Sebastián Piñera appeared on national television to announce that: “We are at war with a powerful, ruthless enemy,” seeking to condemn the material damages and, most of all, downplay the legitimacy of the citizens’ demands.

A state of emergency was declared, and a curfew imposed in most state capitals. The military was authorized to use violence—which included human rights violations—against any uprisings or cases of civil disobedience. This decision spoke volumes, given that the ‘state of exception’ had been widely used during the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973–1989). Many student, worker, and feminist associations had criticized the country’s economic policies during the previous two decades, but such high levels of public dissatisfaction had not been seen in Chile since the 1980s. Everything finally collapsed in the country that most financial analysts had viewed as an oasis of safety and stability, one of the West’s first laboratories for neoliberal experiments.

Though the effects, modus operandi, and limits of neoliberalism have expanded in myriad ways in recent decades, they always seem to be under the protection of the allied forces of finance and (neo)fascism. They were further refined in Latin America following the military coup d’état in Chile (September 11, 1973) that overthrew the democratically elected socialist government of Salvador Allende, thus dashing revolutionary hopes spawned by the Cuban Revolution in 1959. The coup reflected the fear among the ruling classes that the winds of emancipation blowing through Latin America in the 1960s and 1970s—bringing guerrilla uprisings, peasant movements, anti-colonial discourses, and feminist revolts—might further decimate the economic and political power long held by the region’s oligarchs.

The Chilean dictatorship’s goal was to reimpose the biopolitical structure once used to control human bodies that had begun to slip from the oligarchy’s grip in the twentieth century–a system of exploitation, developed on haciendas and coffee plantations, that was derived from slavery and inspired by European colonial companies operating from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. The reorganization of the methods used for domination led to the development of a two-stage program: one stage delivered a shock by unleashing the free market economic model; the other involved an elaborate necropolitical initiative that launched a low-intensity war waged by foreign interests in cahoots with the military leadership of the Southern Cone countries (Brazil, Chile, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Bolivia). That initiative, created in 1975 and dubbed Operation Condor, was responsible for covert actions and executions designed to eliminate social organizations, labor organizers, journalists, students, leftist activists, guerrilla fighters and their families; it represented the institutionalization of State terrorism through the murder and disappearance of tens of thousands of opponents over the course of a decade or so.2

The politics of economic obedience and military control were thus an updated version of the legacy of imperial and colonial systems for the accumulation of capital based on extractive logics (the exploitation of people and natural resources). In the last few decades, the neoliberal paradigm has developed sophisticated methods for inserting itself into the social fabric and influencing even the most intimate areas of people’s lives. Neoliberalism is clearly not just a financial narrative; it is deeply embedded in the State machine and directly impacts feelings and social and emotional practices.

Ever since the neoliberal promise was introduced in Chile, many artists and activists have taken a critical approach to this concept of life based on consumption and accumulation. For some of them, the dictatorship was more than just an interruption of the democratic process; it represented the expropriation of joy and of the desire for social change. It involved the violent imposition of a docile lifestyle and an economic narrative on the population.

Cecilia Vicuña at her installation A Journal of Objects for the Chilean Resistance, 1974, Meeting Place, London.

A Healing Aspect

A few months after the military coup, Cecilia Vicuña, David Medalla, John Dugger, and Guy Brett were in London, where they created Artists for Democracy. The group took part in the demonstration jointly organized by the United British Labour Movement and the Chilean Solidarity Campaign, in Trafalgar Square and, at one defining moment, unfurled a huge piece of fabric emblazoned with the message Chile vencerá [Chile Will Overcome], a work by Dugger inspired by Vicuña’s account of the violent overthrow of the Allende government. Artists for Democracy had already proposed the international “Arts Festival for Democracy in Chile” (October 1974) in solidarity with people fighting for freedom all over the world. The festival was a success thanks to hundreds of volunteers and artists who came together to speak out against the dictatorship.

Vicuña had just created a series of works called precarious that were designed to make strong statements on behalf of the political and creative resistance. Under the title A Journal of Objects for the Chilean Resistance (1973–1974), some of them were presented at the festival, where they contributed to the global spirit of anti-imperialist struggles. Vicuña’s precarios are small, delicate sculptures made of bits of wood, rocks, feathers, pieces of string, fabric, and discarded vegetable and mineral debris that she found on the street. Their material form evokes sacred offerings and the remains of native peoples, indigenous settlements, and Andean wak’as (sanctuaries, idols, temples, and graves).3 The pieces in her installation underscored the medicinal, healing, and shamanic aspects of art, whose function is neither to colonize nor to possess but to foster change in structures both microscopic (invisible phenomena) and macroscopic (perceptible physical experiences). She describes her precarious in eloquent terms: “Politically, they stand for socialism; magically, they help the liberation struggle; and aesthetically they are as beautiful as they can be to comfort the soul and give strength."4

Cecilia Vicuña, Venda [Bandage], from the series Journal of Objects for the Chilean Resistance, 1974. Stick, thread and fabric. Courtesy the artist.

Cecilia Vicuña, Chamán herido [Wounded Shaman], 1987. Precarious object, mixed media, wood, cotton, and twigs. Courtesy the artist.

Using found materials—what she calls basuritas (little rubbish)—was a way to unearth the meaning and energy of things marked as disposable by a profit-driven society; it was also a way to establish a dialogue with the sea, the wind, and the natural world. Vicuña takes a cyclical approach to the creative act—she considers works of art to be trial runs, metamorphoses, or poetic transitions rather than final objects—that was derived from indigenous ontologies and an understanding of sacred beliefs that challenged Western ideas about time, such as the Andean philosophy that views the past and the present as part of a single non-evolutionary concept of time called pacha.5

Her explorations at a material and poetic level hinted at a subtle but tremendously potent idea, which was that modifying language could unleash changes in the structures of desire and open escape routes from the mechanisms of power. Vicuña imbued debris and discarded items with dignity; she honored the balance, complementary nature, and reciprocity of the natural world without submitting it to violence of any kind. Her works focused the question on how to reconnect the scattered parts of what today might be called ecological justice—an assembly of many different worlds and multiple forms of awareness. Her view of the world we share, therefore, does not privilege human society above all else; on the contrary, her work rejects the anthropocentric and hetero-patriarchal fantasy that anoints human beings as the dominant species on our planet (superior to plants, animals, and other organisms) by suggesting symmetrical, symbiotic relationships between different forms of life and various elements. Vicuña undermined and thwarted the promise of neoliberalism by the animation of joy as well as the healing or magical aspect of art, reclaiming non-Western poetics and knowledge that the dictatorship’s pragmatic policies sought to demolish and obliterate at all costs.

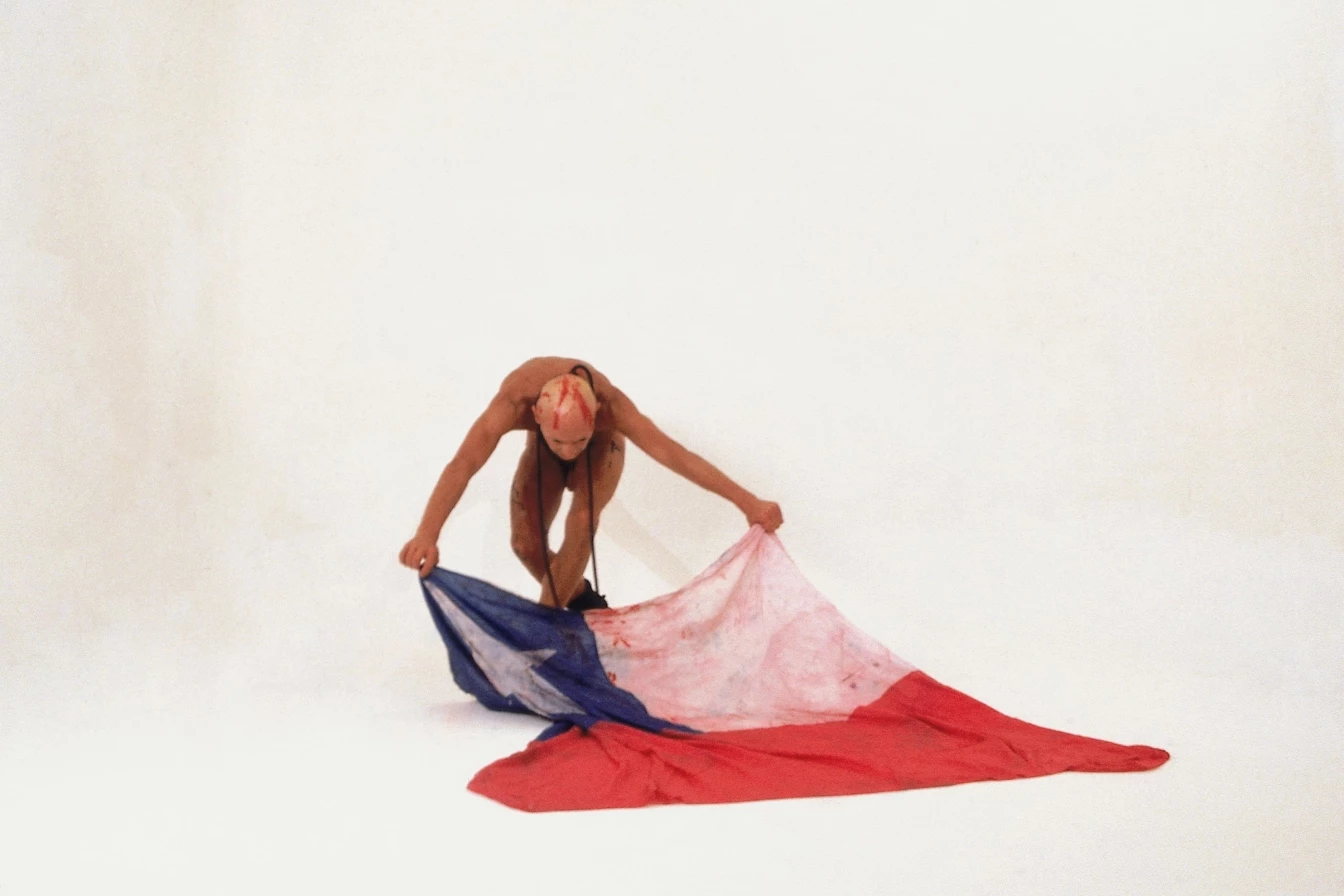

Francesco Copello, El mimo y la bandera, 1975. Photo: Giovanna Dal Magro. Courtesy Rosa Copello and Die Ecke.

Francesco Copello, El mimo y la bandera, 1975. Photo: Giovanna Dal Magro. Courtesy Rosa Copello and Die Ecke.

The Liberation of Desire

Responding to that devastation from a ritual and sensitive perspective rather than a purely rational one allowed Vicuña and many artists to show how the military’s authoritarian regime led to the imposition of a patriarchal mandate, a religious-family model, the repression of indigenous knowledge, and the Westernization of society. Converting long-subordinated, exploited, and enslaved people into consumers was a way of institutionalizing the neoliberal concept of State, society, and market by introducing individualism, privatization, and entrepreneurship as the country’s prevailing values.

The artist Francesco Copello, who was also living in self-imposed exile, created works that protested against the regime’s attempts to expropriate the meaning and power of human bodies. In May 1975, at the Galleria Diagramma in Milan, he presented El mimo y la bandera [The Mime and the Flag], a choreographed piece featuring a bloodstained Chilean flag. With his head shaved, his face painted white, and his body partly naked, he performed a cathartic dance that turned the symbol of Chilean identity into a metaphor for mourning. Giovanna Dal Magro’s photographs show Copello miming a narrative of the military coup d’état. His decision to use mime rather than words seems to allude to the relationship between pain and language—the inability to verbalize trauma—that demands an approach to communication and memory that goes beyond the limits of conventional writing.

His performance, with the flag wrapped around his shoulders, could be interpreted as a subtle exercise in cross-dressing. Copello turned the fabric into a cloak-fiction-territory from which to transcend the boundaries imposed on human bodies by the violent standards of national identity. With his own body partly naked and partly adorned with makeup, his delicate movements gave shape to a way of being that was the antithesis of the dictatorship’s concept of an ideal neoliberal citizen; that is, a heterosexual, Christian, healthy, highly productive, obedient, market regulated person whose moral imperatives are driven by an economic view based on a cost-benefit analysis.

The flag draped across Copello’s naked body hinted at the fragile nature of the concepts of citizenship and nationality—the extensions of a law that draws the line between decent and obscene, civilized and primitive, healthy and sick. He performed a sort of mating dance in which both protagonists (the mime and the flag) seemed to be flawed and incomplete meanings that did not meet the official standard. Copello carried the flag on his back to look like wings or spread it on the floor as if to hide something or wrapped himself in it and adopted ironic or heroic poses. As an alternative to the protocol of patriotic and military submission demanded by the country’s national symbol, he offered the rebellious sensuality of his own migrant, homosexual body. It was like a “cathartic assault on the nation’s sacred flame,” as he so eloquently expressed it several years later: “a brave move, that scared me to death, in my constant wanderings, in and out of hotels/always on the move, looking for the best option.”6

Copello knew that if he’d lived in Chile in 1975 his body would have been subjected to violent discipline by the military heterosexual regime and, sooner rather than later, would have been marked for death. He was the embodiment of what the neoliberal system considered disposable. Like those who are seropositive, undocumented, transgender, sick, imprisoned, or have cognitive and functional diversity, Copello inhabited a body that refused to satisfy the productive demands of the capitalist system. His works of art seemed to attempt a dissident exorcism of the government’s model of the exemplary, decent Chilean citizen in a head-on confrontation with the false narrative of the country’s moral, reproductive, and sexual wellbeing.

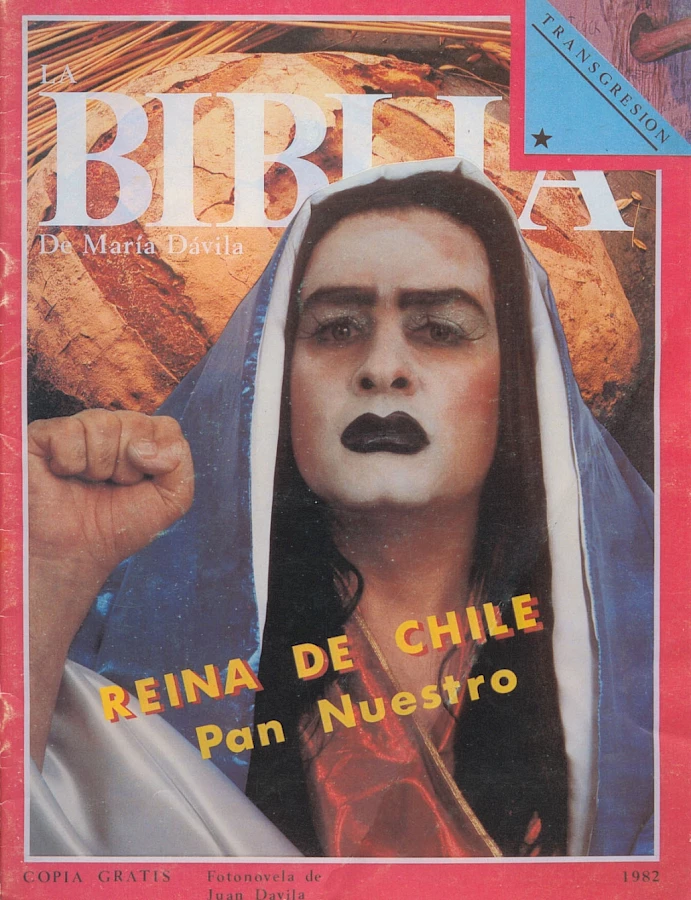

Dramatizations of political power and their queer upending of authority offered crucial opportunities to challenge the regime’s discourse. In 1982, in his performance of La biblia [The Bible],7 Juan Dávila presented two images in which he used the Chilean flag to engage in a potent display of cross-dressing. In the first image he appeared wearing the flag as a veil, portraying himself as the Virgen del Carmen—the patron saint of the army and an icon of military culture—while making a raised fist with his right hand as a nod to left-wing struggles. Wearing lipstick and with his face painted white, along with a statement that said: “Queen of Chile. Our Bread,” Dávila sought to show how the dictatorship’s policies of starvation and extermination were hidden behind a veneer of religious approval. According to the researcher Fernanda Carvajal, the clenched fist was also a reference to a promiscuous “link between the national Catholic visual discourses and those of the left (both with their heteronormative violence and inherent homophobia)”.8 The second image shows Dávila with no makeup on his face, wearing the veil-flag around his shoulders, above the statement: “Liberation of Desire ≡ Social Liberation.” He is naked, holding his left arm against his head in a gesture of confrontation and defensiveness, his hand tightly bunched into a clenched fist. In response to the spread of the national-Catholic hegemony in educational, medical, and police discourse, Dávila offered a (homo)erotic portrayal in which the flag was used as a sort of sexual shroud to cover and uncover a homosexual body. The transvestite Virgin’s veil and the flag-shroud also alluded to the violent measures the Christian religion took to “impose a colonial gender ideal throughout the Americas” and become “the symbol of indigenous genocide."9 Offering joy and magic alongside serious politics (as in the case of Vicuña) and unleashing forms of non-normative desire (as Copello and Dávila did) were ways of disrupting the entrepreneurial spirit and the prohibitions imposed by Western patriarchal authoritarianism. These aesthetics and modes of affective affiliation were considered a symbolic threat to the country’s economic and moral order.

Juan Domingo Dávila, La Biblia de María Dávila, ca. 1982. Photo: Martin Munz. C-print on paper, 120 x 80 cm. Colección Museo de Arte Contemporáneo (MAC), Universidad de Chile.

Human Bonds and Shared Experiences

Forty years later, the neoliberal narrative is still driving social planning in Chile. It was, in fact, the post-dictatorial democratic transitions in the Southern Cone countries that introduced the neoliberal model as a false synonym of democracy. That model took root all over Latin America on the heels of the 1989 “Washington Consensus” and its program of reforms designed to weaken the State, deregulate markets, and give the private sector a strong hand in the management of local economies.10 The social upheavals that rocked Chile in October 2019 were once again, as in earlier years, a protest against the hijacking of the State by financial interests with the tacit approval of a judiciary that obstructs the due democratic process—a Constitution that was approved during the dictatorship. “It’s not 30 pesos, it’s 30 years” was a trenchant slogan that resounded in many parts of Chile.

As happened during the dictatorship, neoliberalism has brought about a dismantling of the organizational structures of the social movement, which is constantly being accused of carrying out terrorist attacks. A good example is the Piñera administration’s recent use of the reformed Antiterrorism Law—originally enacted in 1984 by dictator Pinochet—to criminalize and target Mapuche indigenous activists. The October riots were the latest in a long succession of citizen demonstrations that included the marches organized by university and high school students in 2011 to protest a deficient and privatized educational system; the long-standing complaints of the Mapuche community and other indigenous peoples who are demanding that the government return expropriated territory sold off to businesses and calling for a constitutional acknowledgement of their rights and their communal use of land; the demands of workers who protest against the privatized pension system; and the rise of feminist and sexual dissidence movements that clamor for abortion rights and bear witness to institutional hetero-patriarchal violence. The images, slogans, and performances used in many of the recent demonstrations have sought to reconnect with aesthetics at a political and therapeutic level, appealing to the sensitive structure of human bodies and working to break the dominant male, political, and religious order.

These creative statements, arising from art groups and civil society, show a preference for process-based, ephemeral, and craft forms. This can be understood as a desire to have a direct impact on the body, on how we look (at ourselves), and on language, gestures, and habits, giving rise to collective conversation and new ways of coming together. The political power of these actions and representations is also based on their ability to build spaces for recognition and empathy. Neoliberalism, however, has also sought to develop strategies of control and production originating in the area of feelings and emotions. Dealing critically with these sophisticated modes of re-territorializing capital has prompted multi-disciplinary artists and activists to come up with tactics to fracture the fabric of submissive subjectivity encouraged by the dictatorship. These actions have been altering public space and using language to say ‘we’ in new ways, reclaiming care and joy as undomesticated expressions of political conflict.

The latter trend has been repeatedly pointed out by feminist activists. In the history of capitalism, the historical work-oriented exploitation of women’s and racialized and enslaved people’s bodies is closely aligned with a willingness to treat nature as a form of merchandise. Neoliberalism can therefore be seen as just another name for an obedience to an ecocide, patriarchal, heteronormative order that is committed to racial supremacy. The feminist anthropologist Rita Segato defines it very well in her description of a confrontation between two opposing views of wellbeing: on the one hand, a historical project focused on things, that controls life and creates individualism; and, on the other hand, a historical project focused on bonds, that fosters reciprocity and creates community.11 What can create genuine human bonds when finance and fascism are allied and the neoliberal ‘entrepreneurial self’ has been successfully socialized as common sense?

LASTESIS, Un violador en tu camino [A Rapist on your Path], November 29, 2019. Collective action in public space, Valparaíso, Chile. Courtesy LASTESIS.

Shattering the Spell

“The rapist is you / and the cops, / the judges, / the State, / the president. / The oppressive State is a macho rapist.” These lyrics are from the song and performance Un violador en tu camino [A Rapist on your Path] by the feminist group LASTESIS (Sibila Sotomayor, Daffne Valdés, Paula Cometa Stange, and Lea Cáceres), originally created as part of a theater piece. The song draws on ideas expressed by feminist activists, theorists, and organizations to condemn the normalization of violence against women; the title subverts the motto “Un amigo en tu camino” [A Friend on Your Path] that was used by Chilean police in the 1990s. On November 20, 2019, the LASTESIS group first performed the song in front of a police station in the city of Valparaiso, Chile.12 The piece was recorded and uploaded to their YouTube account. With their eyes blindfolded, the women stood in rows imitating how they are treated by police officers and soldiers, condemning the impunity and responsibility of institutions in the systematic murder of women. From the moment it was performed in Chile, the song launched an unstoppable wave of street protests around Latin America and the world—public actions with hundreds and sometimes thousands of women denouncing femicide and reclaiming female sexuality. The lyrics have since been adapted to local concerns, and translated into many languages, including Mapuche, Quechua, Portuguese, Greek, Catalan, German, Turkish, Hindi, Arabic, and sign language.

The impact of this fiery performance further fueled the social unrest directed at Chile’s Piñera administration. The song Un violador en tu camino was propelled to notoriety by the power of recent feminist struggles all over Latin America, such as the Ni Una Menos [Not One (Woman) Less] movement in Argentina in 2015 and the campaign in support of legal, safe, and free abortion launched in 2018, symbolized by the green handkerchief that was also used by the LASTESIS group in their performance. Their song was an affirmation of a feminist togetherness, transforming public space into places for collective care and political education. The event can be seen as part of a long history of social and creative protest marked by the prominent public role played by women—whose aesthetics have, however, frequently been dismissed by men as having little cultural value.

For example, in Chile in the 1980s the feminist and human rights group Mujeres por la Vida [Women for Life] staged fleeting protests against the dictatorship, such as No me olvides [Don’t Forget Me] (1988), consisting of black posters with silhouetted human shapes and provocative messages addressed to people on the street; or in April 1986, women marched with their eyes blindfolded, carrying banners and holding white canes in imitation of the blind. Mujeres por la vida sought to disrupt the sense of normality being fostered by the Chilean military regime, and to keep alive the memory of those who had been tortured, detained, and disappeared.13

Recent mass demonstrations by young women demanding legal abortion and control over their own bodies and reproductive rights are part of the long history of opposition to the ongoing fascist campaign of cruelty and terror that allows extreme arguments for capitalist production to demand obedience to male domination.The confluence of demands by women and indigenous communities—especially the struggle of the Mapuche peoples—has shown that the wave of protests has not just tried to rupture the political and economic paradigm; it has also sought to undermine the male, religious, Western, and colonial cabal that has perpetuated a violent history of subordination. The new grammars of social protest have made giant strides in terms of what can be imagined and said, severely weakening the image of the Chilean neoliberal model and forcing the government to negotiate on a range of issues that even include changes to the Constitution.

LASTESIS, Un violador en tu camino [A Rapist on your Path], November 29, 2019. Collective action in public space, Valparaíso, Chile. Courtesy LASTESIS.

Since mid-March, the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic has prompted the imposition of social distancing rules that are being used by the Piñera government as a reason to redeploy the military into the streets. The government’s presence in places such as the Plaza Dignidad—the epicenter of Chile’s recent social upheaval—has angered citizens and social movements. In Chile, as in Brazil, the government’s first reaction was to support the neoliberal argument that it was necessary to safeguard the country’s economy and private interests. Though the pandemic has provided the government with a temporary lifeboat by stopping the public protests, the exacerbation of socioeconomic inequities caused by the failure to invest in social infrastructure—the basic rights to health, housing, education, and water—will show that citizens’ complaints are well founded. Despite the forced truce, social unrest is still widespread and is being expressed via images shared on social media, in slogans, and through demonstrations that put pressure on the government—on March 20, Chileans banged on cooking pots outside their homes, calling on Piñera to institute a country-wide quarantine in response to COVID-19. The deepening of inequalities will no doubt fuel new upheavals; images, songs, and street events will liberate people’s bodies from the state of obedience and shatter the neoliberal spell that was cast in the 1970s. Their demands are clear. Control and obedience are to be replaced with collective organization. The debt-financed lifestyle is to be replaced with an economy released from the game of competition. Instead of the fantasy of individual freedom, they call for a political system devoted to the common good. Instead of extractive policies and extreme profiteering, they demand the deployment of skills that belong to no one and are therefore everyone’s to share. Demands that still echo in the bonds and the energy of the crowd that will return to the streets when the time has come for us all to come together.

March 2020

Translation by Tony Beckwith