Dispatch: A Faceless Future? A brief impression from MSN in its first days

In a dispatch from Warsaw Charles Esche shares a series of reflections and images after his first visit to MSN's new building. Struck by the presence of obscured faces, Esche identifies what he sees as the presence of a 'survivalist future' and a radical, if deliberately camouflaged, future to come.

The opening of the first collection presentation at MSN (Museum of Modern Art), L’Internationale’s new museum in Warsaw, was a little overwhelming. I had missed the building’s inauguration in October last year so this was the first time I could set foot inside. It was an emotional moment for me, as I imagine for many. A promise and potential that was 20 years in the planning had been fulfilled. That the museum has, in the process, risen above so many pitfalls; successfully negotiated with unreliable, unfriendly and risk-averse governments; maintained support from national and international artists and colleagues; and still delivered architectural and artistic clarity, makes it a truly remarkable achievement. It felt like a moment of celebration, and paradoxically for a ‘modern museum’, also a little anachronistic.

New public museums in Europe, founded on principles of artistic freedom, diversity and access, are not common in the 21st century. The baton has been passed on to the excessively rich individuals who characterise so much of our current time. Here, in Warsaw, an old idea of democratic culture is resurrected and holding that tradition puts a great burden on the fledging art institution. Can it help make a start on rebuilding an ethos of publicness and artistic value for these times – an ethos that would need to express itself in new versions of commoning, its participants and their rights and responsibilities? In doing so, can it encourage the surviving public cultural infrastructure in the rest of Europe to revive itself and cut loose from the defensive, risk-averse posture it currently assumes. Such expectations are not easy for the building and all its activities to carry but, on first impressions, it feels sturdy enough. I wish it good fortune and will fight to support it in whatever ways I can.

In the light of these unavoidable expectations, the classical presentation of the collection that opens the programme makes a great deal of sense. This is a museum that needs to root itself, not only in the city and its communities but also inside itself. It needs to establish traditions and set a foundation from which it can move, build, react, deflect or undermine the various possible futures that await it. I say ‘classical’ because the building, in its intense whiteness, makes a clear reference to the white cube and the late 20th century museum style of the United States of America. While that might not be where Europe’s affection now lies, it is certainly where all its modernity was eventually sourced, after the political regimes of the last 100 years did away with any effective homegrown alternative. A museum that takes 1990s New York as its departure point in 2025 Warsaw seems well prepared – aware of its past as it opens to a different present.

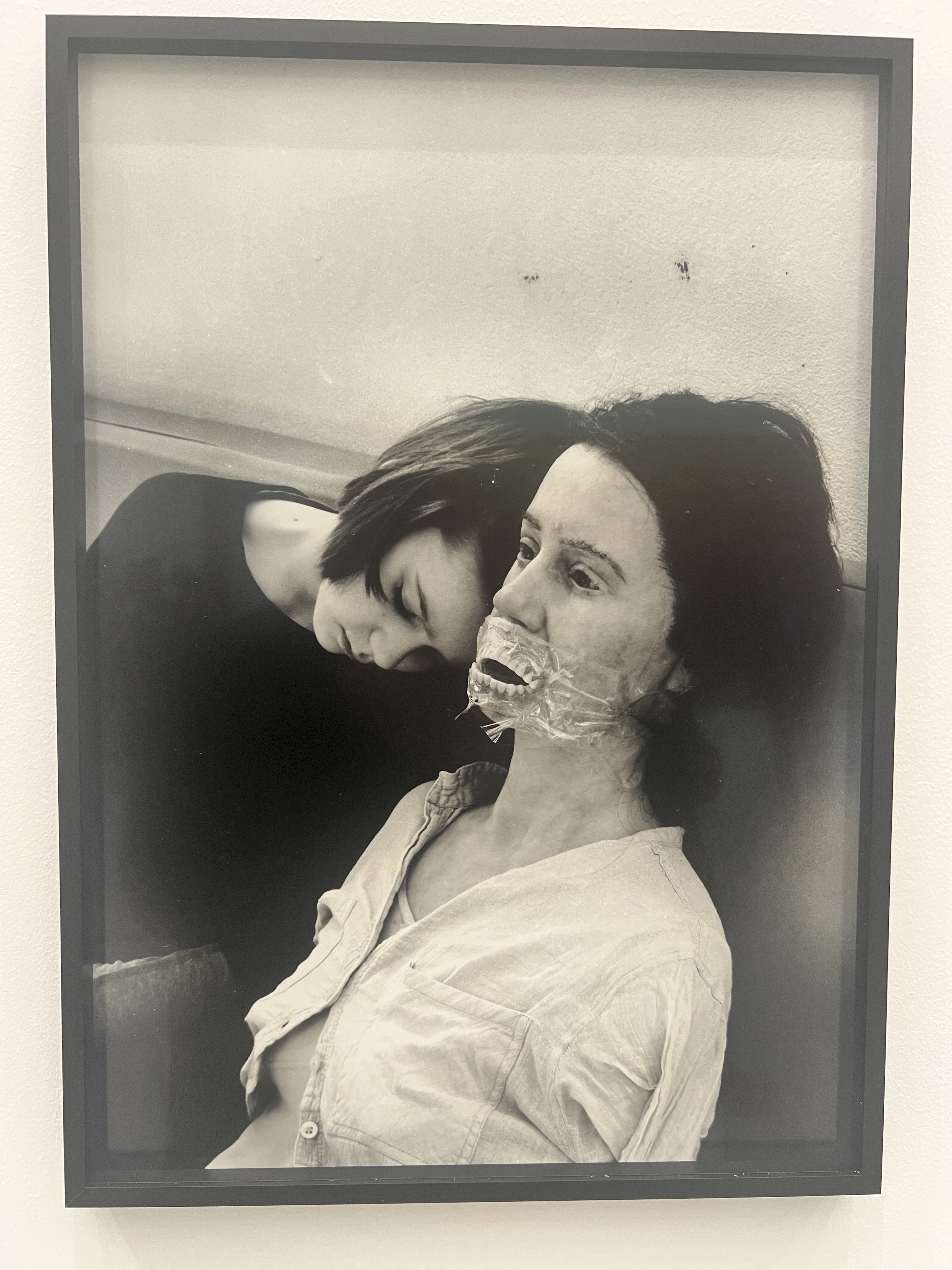

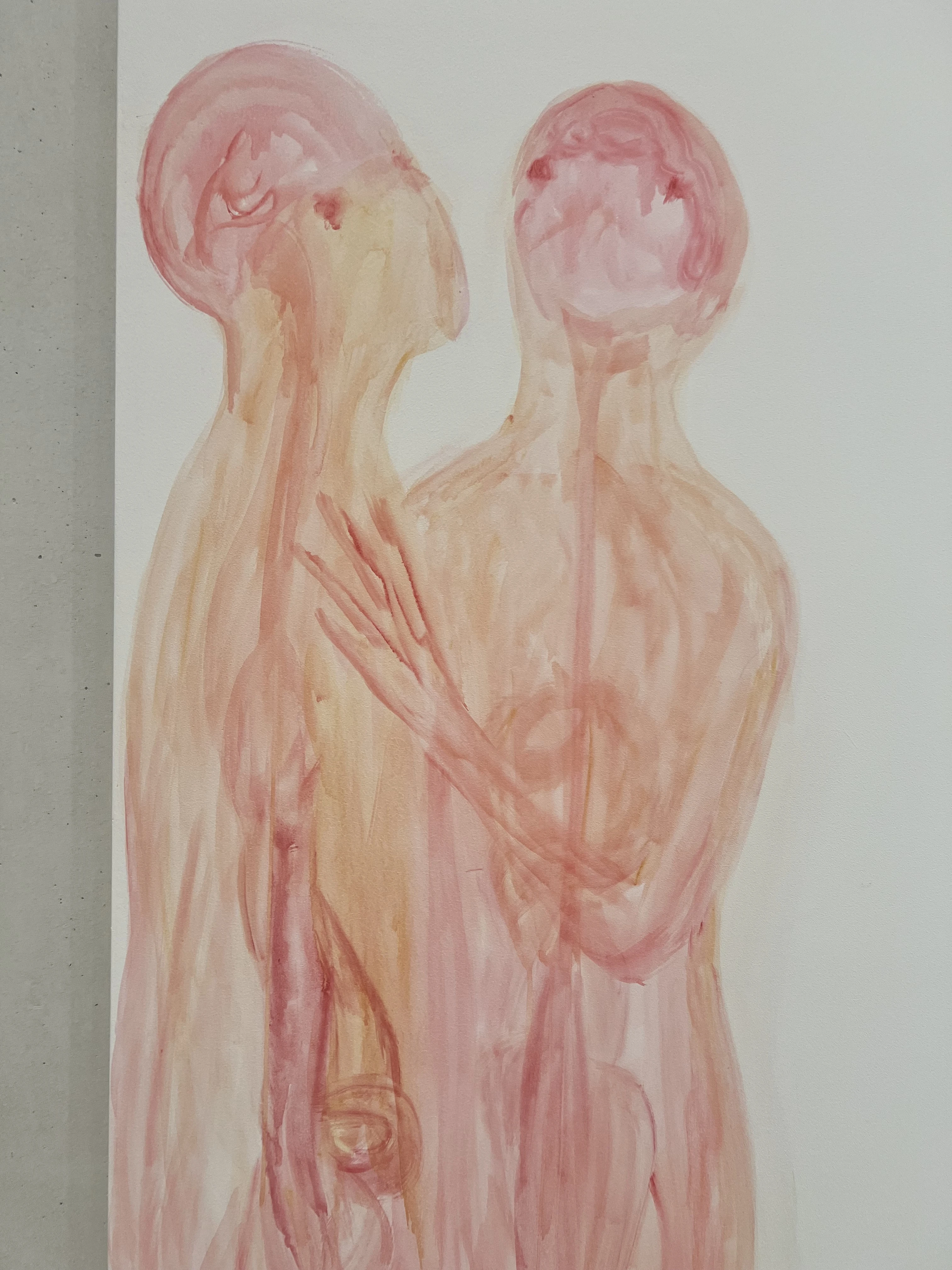

The four complementary exhibitions, beyond their orthodox presentation, each had their moments of surprise and revelation, whether in a newly unearthed Abakanowicz; an intelligent attempt to integrate socialist realism into engaged art practices; or a jewel of a painting by Gülsün Karamustafa that (rightly) insists on sewing the red flag as a symbol of potential even here in post-Solidarność, post-Kaczyński Warsaw. The last chapter of the collection, at least as I saw them, is dedicated to the Dark Planet and to what feels like an honest recognition of a survivalist future. What struck me most in this display, though it wasn’t identified explicitly in the exhibition discourse, was an absence that was possibly visionary. There are almost no fully formed faces in any of the artworks, despite their being many bodies represented. Here are a few of my bad snapshots as illustrations but the impression I took away from Warsaw was much more powerful than they convey. My thoughts turned around these faces as amorphous, formless shapes or distorted, hideous collages as forms of resistance. Isn’t this erasure what undermines both identity politics and its ‘anti-woke’ opposite. Wating to force people to be what they look like – in the judgement of the powerful – doesn't work if their gaze is blocked, their assumptions confounded and the visual is reduced to a bare expressionless palette. Naming gender or forcing race or sexuality onto these creatures makes little sense – these faces are simply not in that game. Of course, such identitylessness is not without its dangers. Cultures, traditions, beliefs, knowledges need to be passed down in new ways not reliant on knowing what and how much it is appropriate to give a person access by sight alone. But then sight was never enough and those new ways can be navigated. Vision is anyway a traitorous sense because it leaps to assumptions and conclusions much too quickly. The visual arts should be, and is becoming, less visual as it deals with the present. Thanks to Warsaw’s ‘Dark Planet’, a strategy of becoming faceless suddenly opens up to me. It seems to be a viable path for a future that does not simply repeat the 20th century in all its absurdly horrific ways and the MSN, a museum that opened with an appropriately classical decorum, turned out to be just slightly obscuring a much more radical potential to come.

Aneta Grzeszykowska, Mama #20 [Mama #20], 2018

All works: Collection of Musuem of Modern Art, Warsaw. Photos: Charles Esche

Tala Madani, Becoming Brilliant II, 2013

Cathy Wilkes, Untitled, 2014

Cathy Wilkes, Untitled, 2014

Ewa Juszkiewicz, Untitled (after Abraham van den Tempel), 2013

Tau Lewis, Angelus Mortem [Angelus Mortem], 2021

Kateryna Lysovenko, One life, 2024

Anni Puolakka, Timanttimaha / Diamond Belly, 2018

Related activities

-

–MSN

Multicultural Youth Center

The Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, together with the confederation of museums L'Internationale, is establishing a Multicultural Youth Center. This is a unique space for 16-24 year olds to explore and develop their creativity, make new friends and hang out in a friendly and supportive environment.

-

–MSN

Archive of the Conceptual Art of Odesa in the 1980s

The research project turns to the beginning of 1980s, when conceptual art circle emerged in Odesa, Ukraine. Artists worked independently and in collaborations creating the first examples of performances, paradoxical objects and drawings.