Nadia Vadori Gauthier, One Minute Of Dance A Day, April 8, 2016, dance 451. Image courtesy the artist.

Sarah Werkmeister (L'Internationale Online): How do you think we can go about resisting or changing the narrative of (climate) catastrophism while at the same time, allowing new and truly inclusive narratives to form? In this process of changing the narratives, is it possible to avoid the subjugation of the agencies of the many constituencies affected by climate change?

Barbara Glowczewski: Last year, Christophe Laurens and I wrote the following for a conference on the Anthropocene (Glowczewski & Laurens 2015):

Writers on the lookout for the land that has been orphaned of its memory, through the lack of human beings capable of reading ancestral signs, try to create constellations of words and images that awaken us to consciousness, by revisiting, through strife and joy, constellations of live connections with the sky, the sea, the wind, the mountains and everything in existence. Would it not be our task, as teachers or researchers trying as we do in anthropology and architecture to outline existences in their living environment, to find the words to animate the Earth, rather than feed the debates that constantly predict its death?

In Central Australia in the 1980s, I witnessed a time of social utopia when desert people, especially the Warlpiri who had gained a land claim, invented a new way of life combining their ancestral hunter-gatherer semi-nomadic knowledge with a semi-sedentary life in old reserves equipped with schools and houses, traveling by car to "settle down country" on their ancestral lands to establish outstations with solar power partly funded by royalties from gold mining. Today, they try to oppose uranium mining on their land and they have lost the self-determination of their councils and their bilingual education. But they continue to paint incredible art that spreads across collections and museums while investing in digital archives in order to be in control of their heritage (Glowczewski 2013).

On the north-west coast of Australia by the Indian Ocean in the 1990s, I witnessed the conflictual politics in the region of the Kimberley of different language groups trying to get native title on their land and develop their own cultural enhancement and sustainable economy including tourism. Today there are many successful initiatives,1 and the Kimberley Land Council has developed a fire management programme with Aboriginal traditional techniques which by reducing wild fires reduces carbon emissions:2 this programme gives to the traditional owners involved a green income which is sponsored by Shell but many families also oppose the destruction of their country by fossil fuels and fracking.3

In the mid 2000s, I lived on the north-east Pacific coast of Australia and investigated the process of inquest that followed the violent death of an Aboriginal man, Cameron Doomadgee,4 in custody on Palm Island on 26 November 2004; I also followed at the Townsville courthouse the committal hearing of some twenty six Palm Islanders prosecuted for a "riot" calling for social justice a week after this death (Glowczewski & Wotton 2008/ 2010). My priority for thirty five years has been to enhance Indigeneity's own cosmopolitics using multimedia to promote their voices through writing and various events, highlighting Indigenous creativity in art, performance and political struggle.

For me, such past and current struggles of Indigenous people all around the world are inspiring to ponder narratives that oppose current dehumanisation and the real threat pending on the planet. Videos of young Indigenous people speaking at various forums, which are circulated through social networks also offer narratives calling for change, even when the speeches are old, because they are still current.5

If these people represent more than 6% of the world population, other people who have been dehumanised in the race for affluence are increasing more and more and, with the rise of migrations and fugitives, poverty, etc., they are obliged to invent their livelihoods daily as they necessarily impinge on the reigning order, as evidenced by the recent destruction of the so-called "jungle" in Calais. This shantytown that gathered 6,000 refugees of all origins demonstrated in the space of one year, in various reports and mapping conducted in October 2015 by the National School of Architecture in Belleville, incredible inventiveness in the heterogeneous use of recycled materials, the ability to live together in spontaneous neighbourhoods by country of origin, sociability in the shared places (shops, a school, a church, a mosque, a theatre, electricity and water points) and the art of making an intimate and distinct "home" with almost nothing, in very precarious conditions, and of course, as in all popular areas in the world, prone to danger, violence and crime...6

S.W: In terms of thinking about what art can do beyond representation of the climate change problem, how do you think aesthetics and ethics can work holistically (within or outside of the art world or art museum setting) to picture new futures? In your observation and long-term work with the Indigenous communities in Australia, where can effective examples of relations of ethics and aesthetics to politics be found?

Brook Andrew, Building (Eating) Empire, 2016. Installation, mixed media (linen, metallic foil, neon, rigging, sandbags), variable dimensions. Installation view, Encounters, Art Basel Hong Kong, curated by Alexie Glass-Kantor. Courtesy of the artist, Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne, and Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris and Brussels.

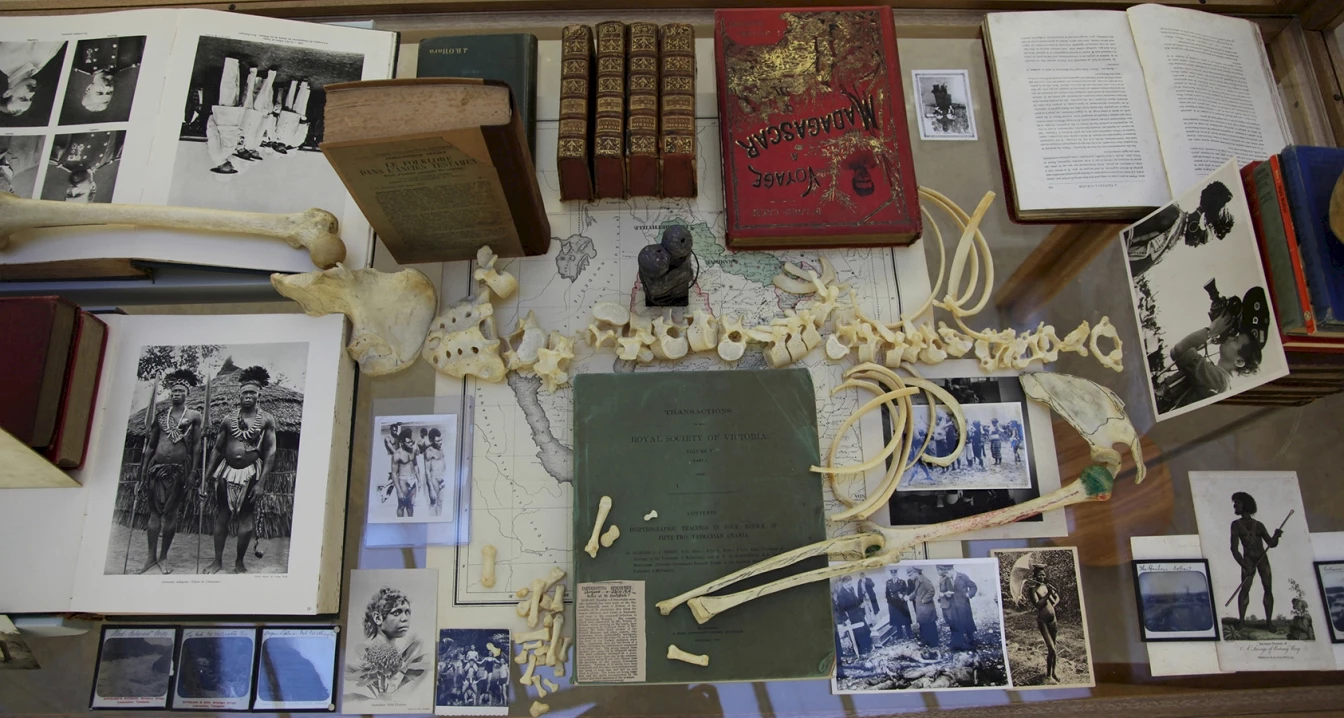

Brook Andrew, exhibition view of Anatomy of a Body Record: Beyond Tasmania, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris and Bruxelles.

Brook Andrew, exhibition view of Anatomy of a Body Record: Beyond Tasmania, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris and Bruxelles.

B.G: Since I wrote "Resisting disaster: between exhaustion and creation" (Glowczewski 2011/ 2016) advocating the way Félix Guattari proposed to ecologically intermingle aesthetics and ethics and analysing several examples of creative responses to catastrophes in Brazil, Africa or France, many things have changed in the world and especially for Aboriginal Australians. Fracking is threatening not only the waters north of Australia but all waters of the continent and elsewhere... In Brazil, Indians suffer genocide, like the Guarani-Kaiowa in the south7, while others are faced with ecocide that destroys all living beings like along the Doce River to the Atlantic Ocean when a dam burst at an ore mine.8

But people continue to produce art as a mode of resistance. For Aboriginal people of the desert, painting their spiritual links to the land on canvas, with acrylics and new colours, was a way to promote such links to help them in their battle for land rights (Smith 2001, Foley & al 2014). Today, Indigenous artists – who claim or not to be Indigenous – invent new styles and experiment with new media to address their heritage, colonisation and the current issues of the world. The best example of such creative artistic investigation is provided by world renowned Melbourne-based artist, Brook Andrew, who reworks colonial archives – from Australia and elsewhere – in relation to his ancestors' sacred design and various imagery combining complex sets of perceptions and emotions.9

For a solo exhibition at Milani Gallery in Brisbane,10 Vernon Ah Kee, an Aboriginal artist from Queensland, created an installation with footage in homage to Lex Wotton, who had been accused of being the ring leader of the "riot" that took place on Palm Island a week after Cameron Doomadgee's death. The artist referred to the control video recorded in the cell of the police station on which the victim is seen dying during twenty minutes in horrible pain from broken ribs and a liver cleaved in half. This tape, that I described second-by-second in Warriors for Peace (Glowczewski & Wotton 2008/ 2010), was shown publicly during the inquest at the Townsville tribunal but it was not allowed during the trial of the policeman responsible for this death, who was acquitted in June 2007. The exhibition, called Tall Man in response to the name given to the giant policeman (accused of other violence on that island and elsewhere), opened in 2010, during Lex Wotton's trial which provoked some media coverage. But in a country like Australia, despite the international reporting, Wotton was sentenced to six years in jail, with four years lifted for time already spent in jail before his trial and a restrictive condition imposing that he would not speak in public. His lawyer managed to get special permission from his board so he could talk at a human rights convention at James Cook University, but after that the court refused to lift his ban of speech. He only got the right to speak back at the end of his sentence, in 2014. We invited him to speak at the Macquarie University in Sydney and he has been interviewed many times since, claiming rights not as a victim but to promote a vision of hope for his people; he now works for the community council where he had already been elected over ten years ago.11 He posts news of discrimination from all over the world on Facebook: about Indigenous Australians, Native Americans but also Black people in the United States, refugees, stories of political corruptions, etc. In a way, if the so-called riot, that I call "civil disobedience", had not happened with its consequence of trial and jail, no hope of pacific resistance would have emerged. After Lex Wotton's class action against the State Government to improve the treatment of Indigenous people in custody, he was honored last June with the Indigenous Human Rights Award for Courage.

Vernon Ah Kee, Tall Man, 2010. Four channel video installation. 11:10 min. Image courtesy the artist and Milani Gallery.

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez (L'Internationale Online): At the UNESCO conference on climate change and Indigenous peoples in Paris in November 2015, some discussions put forward the problem of the appropriation of Indigenous knowledge and heritage, about which you have written on many occasions and in light of the digital archives and Indigenous culture. What was clear from these discussions was the fact that legal tools need to be devised to offer protection to the multitude of Indigenous systems of knowledge so they are not be de-rooted and decontextualised from the communities that survive by using it. Could you tell us about some projects you might know that are oriented towards the protection of Indigenous knowledge and heritage as well as towards its translation for the sake of the survival of the non-Indigenous communities in a meaningful way?

B.G: For decades, Indigenous people have been asking for legal tools for the recognition and protection of their systems of knowledge. The Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples which was ratified by the United Nations in 2007 – with belated support from the United States, Canada, New Zealand and Australia – specifies that: «Indigenous Peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures, including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literatures, designs, sports and traditional games and visual and performing arts. They also have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions."

In 2010, the World Intellectual Property Organization (Torsen & Anderson 2010) proposed a series of concrete options for museums, libraries and archives, institutions which manage different media and expressions of knowledge: audio-visual collections, art and material culture, scientific data. French anthropologist, Jessica De Largy Healy and I commented on such issues: «The complex translation of intellectual property legal and philosophical concepts, in relation to succession rights, the protection of authors and the supposedly free access to data, aims at protecting heritage and recognising its cultural depositories. But it still implies pragmatic limits to their applications according to the States and the concerned people and their economic and political relations of power as well as recent devices generalising the digital misappropriation of any peoples' knowledge and images for the commercial benefit of a happy few. The challenge for anthropologists is to analyse what is at stake culturally, technically, ethically and politically in the forms of transmission, accessibility and control of the patrimonial process". (De Largy Healy & Glowczewski 2014)

A way to respond for anthropologists, curators and museum institutions is also to back legal action undertaken by various Indigenous peoples. For instance, support the recent denunciation by the Human Rights Commission of Apple, Facebook and Google for racism, after they promoted a video game inciting to kill Indigenous Australians as a true experience for settling in Australia...12

S.W: In your text "Resisting the Disaster", you mention that climate change needs to be thought through with a more «...collaborative 'good use of slowness' looking for 'long circuits' in order to grasp all forms of interaction...", and then you go on to talk about refrain, almost as a strategy to operate in in a more responsible way. How would you see this working within not only broader political, economic or social contexts, but also in the field of contemporary art?

B.G: The English word "refrain" translates the French ritournelle which refers to a sort of tune that tends to wind itself, to wrap up inward, digging into some affective memory, like the Italian ritornello in music. For Deleuze and Guattari (1980/ 1987), this does not necessarily refer to music or the sound of birds but also to colours, gestures and so on. They considered that such aesthetic expressions, like the rituals of humans and animals, and also art, trace a territory. Guattari specifies existential territories as real but virtual, constellations of refrains as possible and virtual, flows as real and actual and finally machinic phylums as actual and possible. This ecosophical cartography is abounding in his book The Three Ecologies (1989/ 2000) in which he wrote: «The hope for the future is that the development of the three types of ecological praxis outlined here will lead to a redefinition and refocusing of the goals of emancipatory struggles. And, in a context in which the relation between capital and human activity is repeatedly renegotiated, let us hope that ecological, feminist and anti-racist activity will focus more centrally on new modes of production of subjectivity".

The future is in the hands of the civil populations. This is advocated by Naomi Klein, who was invited by the Coalition Climat 21 during the ten days of the COP21. Thousands of activists gathered13 at the vibrant Parisian art and culture centre, the CENTQUATRE-PARIS. In the Canadian economist's book, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the Climate (2014), there is an underlying message concerning the importance of Indigenous peoples in the fight against the destruction of the Earth. Klein took part in the final street protest called "Red Lines", referring to the threshold of gas emissions that the government officials were supposed not to cross. In the front row of the demonstration, a French dancer, Nadia Vadori-Gauthier, improvised her one minute of dance a day, a new dance she makes and posts online every day as an act of poetic resistance since the Charlie Hebdo journal mortal attack on 7 January 201514. To resist is to create. Many artists working with performance, mixed media and installation explore ways to respond to our world in a way that is not only an "expression" of it but also an incentive to change it. A group of artists, Liberate Tate make performances to denounce the damage caused by petrol companies in front of or inside museums, such as the British Museum. They managed to get a representative of one of the big companies dismissed from the board of a museum as an ethical requirement for art not to be sponsored by a destructive agent.

N.P.B: And how can institutions "refrain"? Could you reflect further on the anti-accelerationist resistance in academic circles, and draw some differences that exist between the notion of slowness in the writings of the French anthropologist Pierre Sansot and the "plea for slow science" which Isabelle Stengers proposes? Do you think one solution to the above-mentioned problems could be in an art institution, a museum – which has historically, in the developing and developed countries of the Global North, been mimicking the arrogance of colonisation, whether over peoples, over the planet, both, or beyond – becoming a slow institution?

"Une minute de danse par jour 08 04 2016/ danse 451 (One Minute of Dance a Day)" from Nadia Vadori-Gauthier on Vimeo.

B.G: The concept of ecosophy forged by Arne Naess in Oslo in 196015 had the merit to shift man from a central position to being only a part of the ecosphere. But the way Naess promoted a form of transcendental vision of the relation between man and nature is problematic when it legitimises an artificially "protected" wilderness ("deep ecology"). Guattari's ecosophy is different: a praxis through art, politics, analysis and new usages of technology to change the relations between all the living forms, including the air we breathe. Such a vision has taken a special accuracy in the current debates around the "Anthropocene" (Glowczewski & Laurens 2015). In his last text a few weeks before his death on 29 August 1992, Remaking Social Practices, Guattari calls for the necessity to «establish ecosophical cartographies that will assume not only dimensions of the present but also of the future", with "choices of responsibilities for the generations to come", that is an "ethico-aesthetics of eco-praxis" as synthesised by Gary Genosko (2009, p. 87).

The apology of slowness by Pierre Sansot who died in 2005 was a nice poetic proposition that remains an invitation to enjoy life like many writers and thinkers have proposed and continue to do so, for instance David Abram in the United States or Pierre Rabhi in France. There have been many different experiments. Some failed, others still work, as reported recently by Pablo Servigne,16 a researcher who denounces what he calls "collapsology" (2015), and now lives with his family in a sort of "oasis" in the Drôme region in France.

George Nuku, Bottled Ocean 2116, 2016. Photo: Mark Tantrum. Image courtesy PATAKA ART + MUSEUM.

Isabelle Stengers responds in her own way to this call by promoting not only slow science but also a form of "science fiction" that, after Donna Haraway's SF as "science fiction", "scientific fact", or "string figures", she relates to the correlations necessary to pass from one string figure to another which always imply a relation. That is, the input of the hands of another person so as to change the string figure.17 The process involved in the transformations of such figures is, for Stengers, an image (but not a metaphor) for experimenting what she calls the speculative gesture which can "slowly" change reality. So maybe an art institution, a museum, becoming a slow institution would be a place for promoting such string figures18 and fiction? Maori artist, George Nuku, who was resident at the French Muséum de Rouen in 2015/2016, states that plastic is sacred. He sculpts it with the participation of museum users, adults or children, into huge assemblages to denounce not just the climate heat but the pollution of the oceans that precipitates the rising level of the seas, and forces populations in the Pacific to migrate and become refugees who are not necessarily welcomed in Australia. Sea rising also threatens the coast in Normandy as represented in his work Bottled Ocean 2115.19

Maybe a slow museum should be especially attentive to collaborating with concerned populations and artists, Indigenous or not, who create new worlds in response to traumas of the past and the present. For instance, the 2015 installation Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3 by Korakrit Arunanondchai mixes history with cosmology, recreating a spiritual presence in a science-fiction ruined city.20 The acceleration of history, in which ongoing events become archived before being finished, is a real issue to be thought about in a slowed-down, more thought through process, both within art and within cultural institutions.

References:

Abram, D. 1997, The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World, Vintage, New York.

Abram, D. 2010, Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology, Pantheon Books, New York.

De Largy Healy, J. and Glowczewski, B. 2014, "Indigenous and Transnational Values in Oceania: Heritage Reappropriation, From Museums to the World Wide Web", etropic 13.2, Value, Transvaluation and Globalization Special Issue, 55.

Foley, G., Shaap, A., Howell E. (eds.) 2014, The Aboriginal Tent Embassy, Sovereignty, Black Power, Land Rights and the State, London, Routledge.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. 1980/ 1987, A Thousand Plateaus. Capitalism and Schizophreania, vol.2, transl. B. Massumi Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

Genosko, G. 2009, Felix Guattari: A Critical Introduction, Pluto Press, London.

Glowczewski, B. and Wotton, L. 2008/ 2010, "Warriors for Peace: the political condition of the Aboriginal people as viewed from Palm Island", (transl. from French, Guerriers pour la Paix, Ed. Indigène Editions, Montpellier), viewed 15 April 2016.

Glowczewski, G. 2011/ 2016, "Resisting Disaster: Between Exhaustion and Creation", Spheres. Journal for Digital Cultures, viewed 15 April 2016 (translated from French 2011).

Glowczewski, B. 2013, "'We have a Dreaming'. How to Translate Totemic Existential Territories through Digital Tools", in A. Corn, S. O'Sullivan, L. Ormond-Parker, K. Obata (eds.), Information Technology and Indigenous Communities (symposium 2009–2010), Canberra, AIATSIS Research Publications, viewed 15 April 2016.

Glowczewski, B. and Laurens, C. 2015, "Le Conflit des existences à l'épreuve du climat, ou l'anthropocène revu par ceux qu'on préfère mettre à la rue et au musée", paper delivered at the conference "How to Think the Anthropocene?", Collège de France, Paris, 5 November 2015, film, forthcoming publication.

Glowczewski, G. 2016, Desert Dreamers, Univocal, Minneapolis.

Guattari, F. 1992, "Pour une refondation des pratiques sociales", Le Monde Diplomatique, October, pp. 26–7. English translation by S. Thomas: "Remaking Social Practices". Translation revised by B. Homes on the basis of the French original, accessible here.

Guattari, F. 1989/2000, The Three Ecologies, The Athlone Press, London, New Jersey.

Haraway, D. 2013, 'SF: Science Fiction, Speculative Fabulation, String Figures, So Far' in Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology, No.3.

Klein, N. 2014, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the Climate, Simon & Schuster, New York.

Sansot, P. 1998, Du bon usage de la lenteur, Payot (Rééd. Corps 16, 1999 et Rivages, 2000).

Servigne, P. 2015, Comment tout peut s'effondrer, Seuil, Paris.

Smith, T. 2001, "Public Art between Cultures : the Aboriginal Memorial, Aboriginality, and Nationality in Australia", Critical Inquiry, vol. 27, pp. 629–61.

Torsen, M. and Anderson J. 2010, Intellectual Property and the Safeguarding of Traditional Cultures: Legal Issues and Practical Options for Museums, WIPO Publishings, Libraries and Archives, Geneva, viewed 15 April 2016.