Sharing and Taking Action through Art. Škart Collective (Belgrade), from 1990 to the Present

Škart, Copy of Coupons (Kuponi), 6 x 4 cm, survival coupons offset print on paper, Belgrade, 1995–2000.

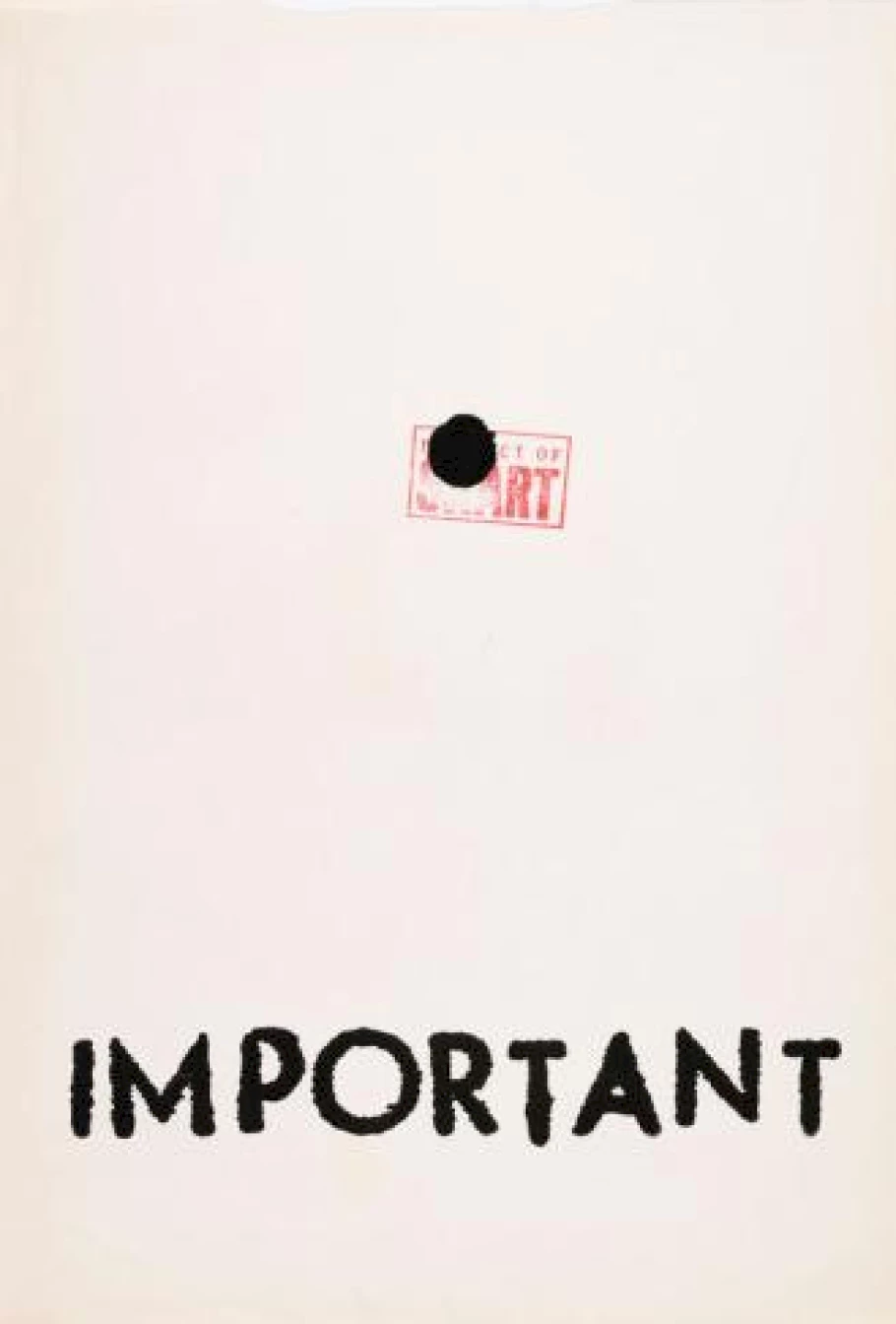

Škart, Important, 1991, silk screen print on paper, stamped, 52.2 × 35.4 cm.

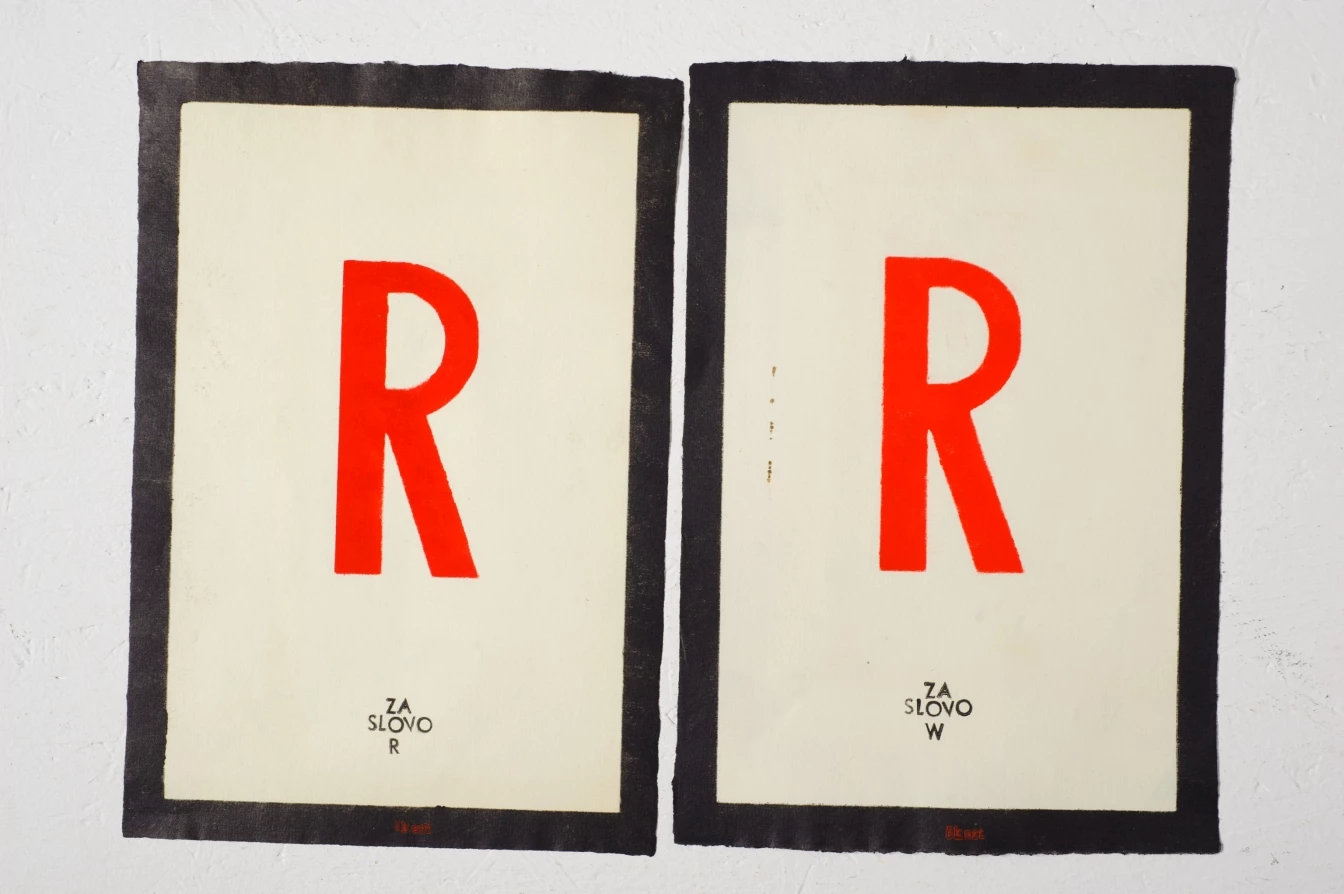

Škart, R – for the letter W, 1991, silk screen print on canvas, stamped, 50.1 × 35.7 cm.

The break-up of Yugoslavia and dismantlement of the socialist regime in the early nineties caused arts and cultural institutions to maintain themselves with ‘minimal function’,1 operating on scarce budgets and under rising nationalism. With institutions’ failure to document and archive during this period, the art of the 1990s in Serbia has been described as ‘decadent’, while the strict control of official cultural institutions left no room for figures of the alternative scene.2 Although some of the alternative institutions founded in the 1970s, such as Student Cultural Center Belgrade (SKC),3 continued to operate, their activities tended to be marginal. From the mid-nineties to 2000 the need for non-state funding sources for culture was mainly met by Soros Foundation, which provided a parallel system of non-governmental, nonprofit organisations. All this resulted in a kind of passivity, whereby artists and cultural workers mostly isolated themselves, ‘expecting the political change that will bring a long awaited “normality”’.4 This situation is particularly relevant when considering the wider context in which to locate Škart in the 1990s.

The following interview is an excerpt from the book Building Human Relations Through Art: Škart collective (Belgrade) from 1990 to present.5 The first step of this archival book project, in the absence of a fully developed archive, was to gather material from Škart’s activities, spread between two cities: Belgrade and Ljubljana. Given the lack of supporting material, an oral-histories approach collects information and memories around their unofficial art practice. Between September 2020 and October 2021, I met the founding members of the group, Prota and Žole, to reflect on Škart’s practice.

Error as a trace of humanity

In a city on the brink of war, Škart came to life in 1990, founded by two students at the Faculty of Architecture in Belgrade – Dragan Protić and Dorde Balmazović, also known as Prota and Žole. The duo decided to name themselves Škart, meaning ‘scrap’, or ‘leftover’ in Serbo-Croatian. Škart’s understanding of the word has positive connotations – such as a ‘refusal’ to remain silent in times of political unrest and rising nationalism, and an active ‘rejection’ of passivity in confrontation with a lack of well-functioning institutions, with the aim of potentially expanding our understanding of artistic possibilities.

The name sums up much of what the group has done over the last three decades: using creativity and minimal resources to reach out to the vulnerable and marginalised in society including the elderly, single mothers, refugees, the unemployed, and orphaned children. ‘How to make people participate in art projects?’ was the starting point for the duo, which remains the core of their practice today. This question has been revisited through numerous collaborations with individuals and groups who are not necessarily from an art circle. The 1990s shaped Škart’s mode of production and communication, as well as their strong aesthetic values of self-sufficiency. In ten years of wars and isolation in Yugoslavia between 1991 and 2001, the transition to a neoliberal economy, followed by the fall of Yugoslavia and its socialism, the lack of financial resources, as well as the deprivation of cultural infrastructures, all resulted in building Škart’s modus operandi: self-organisation, self-production, and self-distribution. Upon these constraints Škart has built its core values: collaboration, care and solidarity.

Seda: How did you two meet and how was Škart formed?

Žole: We met each other in Finland. Prota was a third-year student and I was in my second year. There was a union of architecture students meeting in Finland and fifty students from Belgrade joined, so this was the first time we met. After we returned to Belgrade, we became friends. Prota discovered a studio for etching on the rooftop of the academy, which nobody was using. He proposed that we go and learn classical etching. The atelier was full of dust; it took two to three days to clean it. Later the etching professor started teaching us the basics and gave us the keys to their atelier. It was like our nest. We started practising as typical apprentices, learning craftsmanship. The idea was to produce identical copies, 20–50 copies. But for us it was difficult to achieve … They were not the same. We were making lots of printing mistakes, and one day Prota said, ‘but these mistakes are also beautiful!’ So we started to experiment and make poetry with these mistakes. Because mistakes are very human, nothing is perfect. These mistake-graphics are called Škart in Serbian, so we called ourselves Škart.

S: How did you decide to leave your ‘nest’ and present your posters on the streets of Belgrade?

Ž: It was very organic. Our ideology and politics towards art was shared by the circumstances of the times. When we were at the atelier, we realised that if you want to exhibit in an art gallery, you have to know someone, be part of the scene, or climb the stairs of its hierarchy. We were not willing to do that. We were also in the faculty of architecture (studying in the department of urbanism), which was not popular back then. But we had experience researching the city, so we decided to treat the city as our exhibition space. We knew the techniques of reproduction, so we produced our work in editions of twenty, thirty or fifty copies, as much as we could afford. We started with screen-printing posters and made visual poetry out of Prota’s poems. After, we went into the streets distributing and gluing them in different spots.

Still from video documentation distributing Coupons in Beli Potok village near Belgrade, August 1998. Shot by Miloš Tomić. Courtesy Škart.

Prota: To take part in a predictable art context you also need to adapt your products, to be useful for these exhibitions. We didn’t belong to that circle, and also we did not have something useful for them, something they could treat as artworks. We didn’t care about this. For us the message was important, not the product. That’s why we produced posters; it was a kind of noise in the media sphere, instead of taking part in the art circle. These messages were visual poetry, abstract, self-sufficient messages. Sometimes they had weird meanings or maybe no meaning at all. It was a surreal message in the streets that didn’t try to tell or sell something like the others. It was a new, open space for itself, a space of imagination. For us, it was very important just to open this sphere of experimentation and treat the city as a free ground to spread our message.

S: Yes, those posters were very abstract and poetic, yet they were carrying highly political statements in regards to the chaotic atmosphere in Belgrade at that time. In a way they were subtle, activist interventions.

P: The very first one was: ‘Škart wishes you a nice day’. Complete nonsense … Who is Škart? Because nobody knew who we were back then. Who cares about a nice day? It was slightly childish … Later it went even more abstract like ‘R for the letter R’. Or, ‘Q a rare letter’. In another poster there was just a tiny dot and underneath we wrote: ‘Important’. We didn’t give them a title, nor number them, but insisted on doing this action every week, even though nobody mentioned it or documented it.

S: One early poster of yours says, ‘Škart is again in the museum’. What was this about?

Ž: We did it for our very first exhibition at the gallery in the village, our hometowns: Novi Becej and Zrenjanin. The first action was in 1990. We were a group of four friends; one called himself a punk theoretician, who wrote a text introducing the show, and the other composer friend composed music for the show, based on one of Prota’s poems. So there was sound, posters and poetry reading. We made a poster saying, ‘Škart is in the gallery?’ And the second poster was about the yearly exhibition of architecture students which took place at The Museum of Applied Arts Belgrade, and our work was also included. So we made a poster which said, ‘Škart is in the museum’.

S: For how long have you continued working with posters and distributing them around the city?

P: It was for the whole year of 1991, or a bit longer maybe. We made a new poster and put it in the streets almost every week. Continuity gives you the responsibility to develop a skill, or a responsibility to the city itself, as it was our strategy to spread our messages around the city. And parallel to these street actions and mail art we used radio to reach a wider audience. Radio was very present at the time. In 1991, together with Darka Radosavljević Vasiljević, we created a programme on Radio B92. It was called Škart News; once a week, weird news was on air.

Ž: First we were going out in the streets at 4–5 in the morning to distribute posters and after that Darka was playing our weekly message on her radio show, Sketch Book.

P: It was also a kind of attack on your mind with something you don’t know. One old lady, actually the Serbian actress Rahela Ferai, who survived the Holocaust, read: ‘And now something important: Škart News!’ followed by a jingle, with a very bombastic orchestra playing. And the news is for example: ‘R for the letter R’, then again the orchestra plays … We were making nonsense out of the media, building up free territory for us. Parallel to poster productions the radio programme lasted for one and a half years. Also to reach a distant audience we used mail art; we sent posters anonymously to various people around the world; one-way, without an address.

S: I’m also curious to hear more about the cultural scene in Belgrade back then. I wonder if there were any other arts organisations or cultural institutions with whom you had a common stance and considered collaborating with? And if not institutions, what about other like-minded artists or collectives in the region? For example, during the same time, in the early nineties, LED ART collective was very active, especially in Novi Sad, making controversial street actions; a genius example of subversive art practices. I could find many commonalities with your practice too.

P: In that time maybe we didn’t need collaborators outside of our close circle. With mail art we wanted to communicate at a distance, but for street actions or sociopolitical engagements it needed to be a group structure, which is reachable. We wanted communication, not necessarily collaboration. But for example we collaborated with Women in Black, a network of women dedicated to peacebuilding activities, and this was different. It was not only a short term project; it became ongoing. Also, not many independent art or cultural institutions existed at that time. Rex and Remont came later in 1999. The Student Cultural Center (SKC) had a gallery in the basement and we used to put our posters in the window of the gallery.

Freebies: Same to everyone, or nothing for all

During the early nineties, Škart appeared in the streets of Belgrade with a motivation to ‘build human relations through art’. This marked the entry of critical artistic practice in public spaces in Serbia, resisting the political and social environment. Leaving the studio and going to the streets was not only a conscious choice driven by an urge to communicate with fellow citizens, to overcome polarisation and social isolation, but also to question the place of art in society and its accessibility. Instead of exhibiting at museums or galleries Škart created a scene for themselves, ‘treating the city as their own exhibition space’. Not interested in the idea of producing ‘objects’ of art, but encounters in public space, Škart intended to remind their fellow residents about feelings of empathy and solidarity. Numerous self-produced, self-distributed projects and street actions took place between 1990 and 1996, including distributing poems to passersby as a public declaration of personal sadness (Sadness, 1992–93), or survival coupons of ‘revolution’, ‘tolerance’, or ‘orgasm’ that are printed and handed out to random addresses by post (Coupons, 1997–2000). These freebies, which were mainly self-financed (together with contributions from friends, acquaintances and occasionally, foreign sources), became a gesture of resistance.

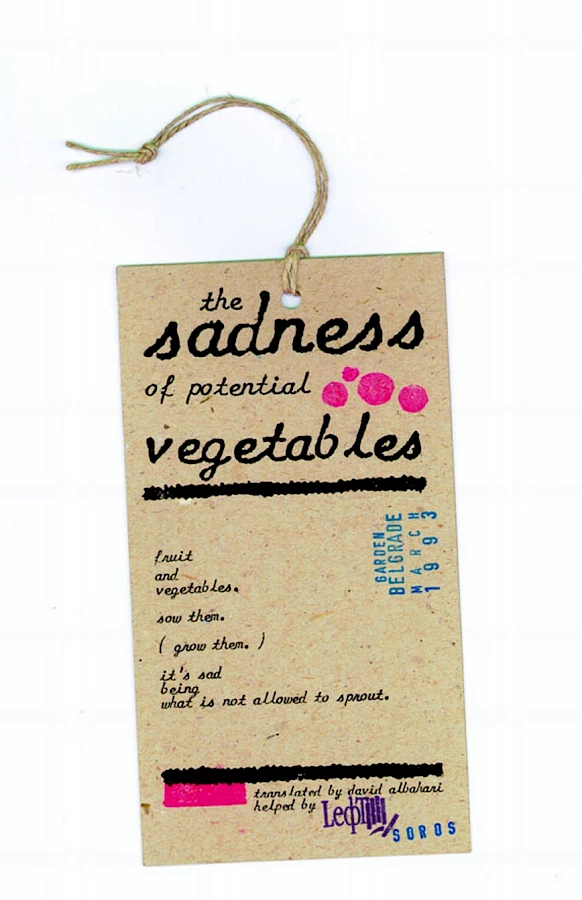

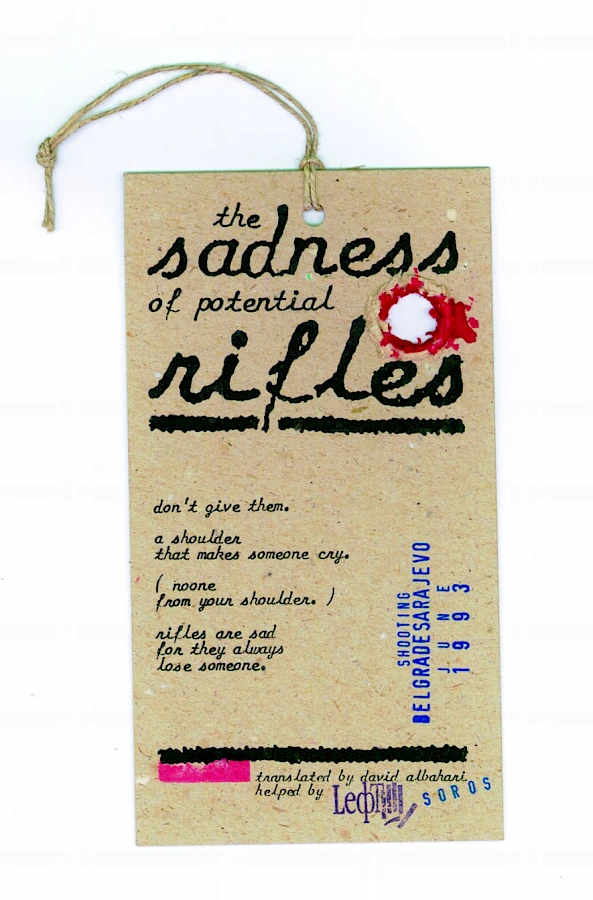

S: For the Sadness project you created twenty-three poems, which were printed on cardboard as a direct commentary on the hostile social environment. Sadness of Potential Vegetables, Sadness of Potential Landscapes, Sadness of Potential Travellers … And you started to collaborate with other people who often joined your street actions too, distributing Sadness cards. You wanted to encourage individuals to motivate and to reflect on social fragmentation, which was strongly present in Belgrade at that time. For Sadness you self-distributed both in Serbia and outside, right?

P: Yes, through street actions and mail art again. We were sending Sadness poems to people important to us, both in the local and international scene. We had quite an open mailing list of individuals from different scenes.

Ž: This initiative came from Prota. He was making a list of people who were important to us, and we were sending posts, all of which were anonymous.

S: And who was on this list?

P: Musicians, architects, literature magazines, film directors, writers … We were not interested in the classic art scene, or the media; but it was important for us to appear, here or there, and still protect our invisibility. This was our strategy. People slowly started to hear about Škart, but they didn’t know who we were exactly.

Ž: Whenever we printed a Sadness poem we used to go out to distribute it on the street in editions of 100–200 depending on our budget. It was expensive at that time to afford screen printing. And again we used the radio for distribution, to reach a broader audience. Thursday morning we would distribute them on the street; maybe the same day, or the following, we had the poem of the week broadcast on the radio.

P: Printed media is somehow frozen, it is on the paper; but the radio is very open so we wanted to use it to spread our message. Something important to add is that these poems were conceptualised; for example, Sadness of Potential Travellers was distributed around railway stations; Sadness of Potential Consumers in front of the department store which had completely empty shelves; The Sadness of Vegetables in front of the farmer’s market. For Sadness of Pregnancy, a pregnant friend was coming with us to distribute. Sadness of Potential Guns was placed within humanitarian aid for Bosnia. We wanted to provoke people to think, why are the trains empty, why are the shops empty, and why had the country ended up under such austerity.

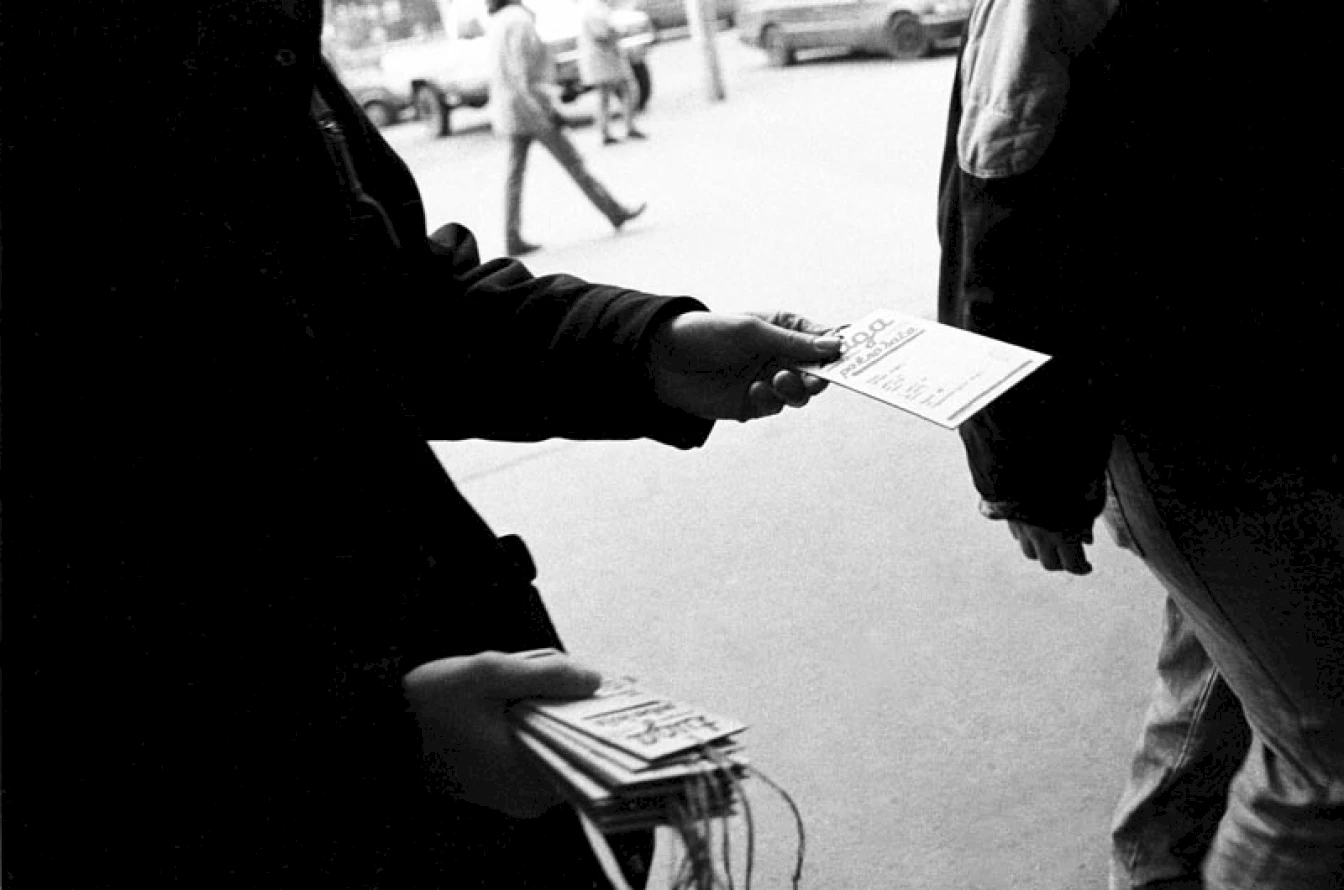

S: What were the reactions to these street actions? I have seen some drawings; I think, Žole, it is you who drew Prota giving away your printed works to the passersby as they hesitate to take them.

Ž: Yes, reactions were exactly like those drawings. It was quite frustrating for me actually. Prota was the brave one, who approached everyone on the street. I was the shy one. So it was a challenge Prota took on, giving away something for free to someone, which they hadn’t asked for. More than half of them were not interested. Most of the time, a few steps later they were throwing these poetry cards into the bin.

S: But you did not give up and continued these street actions and distributions for more than a year, on a regular basis.

Ž: Prota was pushing us to continue. It was a big lesson for me, to realise how people are reluctant or don’t care about art.

P: During the beginning phase of the Sadness project I was also disappointed, but after the second week people started to come and ask for free Sadness prints and started to collect them. This was a sudden brightness for us, that someone needs it, even if it is sadness … which is also necessary because it is a comment on your weekly, political, emotional agenda.

S: Meanwhile you continued working on street actions, self-production and self-distribution. One of your longest-lasting projects, Coupons, first took place in Belgrade, in 1995. You produced coupons, which referenced the survival coupons distributed during shortages of basic needs, like coupons for food and similar necessities. But they further pointed out nonmaterial basic needs, human feelings and desires, such as coupons for miracles, relaxation, revolution, and orgasm. After Belgrade, Coupons travelled to different cities including New York, Stockholm, Graz and others. What I find interesting is how you adapted and adjusted this project, which was highly local and site-specific, into different contexts and localities. For example, in New York, together with students from Parsons School of Design, you made an action on the New York subway, distributing coupons to the passengers. How did you end up taking the project to New York, and what was your experience applying this work to another context?

Distributing Sadness poems in Belgrade, 1992. Photo: Vesna Pavlović. Courtesy Škart and Vesna Pavlović.

Škart, Sadness. A set of poems printed on cardboards. 15 × 8.5 cm, screen print, 1991–93.

P: In 1996, we were invited to the Olympic Art Festival in Atlanta to display the Sadness project. After Atlanta, we went to New York, from one contact to another, and during three weeks of hundreds of meetings we ended up knowing many people in New York.

Ž: We came with big pieces of luggage full of artworks and distributed them at every meeting.

P: And it was always free distribution, we were giving small Sadness books away.

Ž: Then we applied for ArtsLink funding in 1998. We got it and when we were in New York, we met Martha Wilson from Franklin Furnace who invited us to collaborate with students from Parsons School of Design. So everything always goes by recommendation, connection, recommendation.

S: And for this New York subway action you printed multilingual Coupons. I saw the video documentation of the action, in which Prota stands up and says: ‘Ladies and gentlemen, I’m an artist and I would like to give my artwork to you, as a present.’

P: Together with the students we decided to ride the subway once a week and distribute Coupons, because everyone was trying to sell something on the New York subway. It was crazy, full of advertisements. Instead, we decided to give something away. Each person was asked to give coupons to the person sitting next to them and to explain that this is an artwork and a gift from us.

Ž: And people were telling us why they were not interested in them. One guy said, ‘Okay you tell me these coupons are artworks, but if they are artworks they should be in the museum, not given away for free here.’ Then I asked him if he goes to the museums, to which he replied, ‘Of course not!’

P: People think, it is not my world, I don’t belong there.

Ž: Exactly, but I find this answer very interesting. I asked this question for years, why don’t people want to go to museums? Why do they feel art is so far away from them? Maybe it is not understandable, or is it too difficult to understand? There’s something that keeps people from going to museums. However, some things are reachable for anyone; but it seems that art does not have such a capacity to convince people that it is useful.

P: But this is the fight, this is your battle. For me it was always a continuation; poster actions were somehow meaningless, nonsense. But with the Sadness poems we created quite a raw, political agenda, a certain criticism. Even if people throw these poems away, or put them lazily in their pockets. So, even this delayed reaction was important to me. It was important to think that maybe they will look later in their home, maybe another person will see it as well, so the echo of revelation can continue.

S: Yes, it was quite a refreshing gesture to distribute an artwork on the street for free. I find even the confusion it creates for people alone is meaningful. This gentle force, approaching people to encounter an artwork directly, sitting next to them and giving them a piece.

Distributing Sadness poems in Belgrade, 1992. Photo: Vesna Pavlović. Courtesy of Škart and Vesna Pavlović.

Škart, Sadness. A set of poems printed on cardboards. 15 × 8.5 cm, screen print, 1991–93.

Ž: When we were in New York in 1998 we met one of the greatest designers: Tibor Kalman. After a public talk, we approached him and gave him our Coupons and we exchanged telephone numbers. A few days later we were invited to his studio; a huge studio with many employees. He was very interested in what we showed him and then said, ‘Giving something for free in these times is such a refreshing idea indeed!’ I remember his excitement very well, but I was not able to understand back then, since for us it would not be normal to do the opposite, to sell them on the streets for example!

S: Well, today, distributing something for free on the streets has almost a negative connotation; a foreigner approaching and offering you something unwanted … It creates an uncanny feeling. But I liked this twisted approach, how you play with people’s expectations and mindsets. And after twenty years we can still say that it is a radical idea in today’s neoliberal reality in which nothing exists for free … Maybe it is also interesting to add here that, later, Coupons were also displayed in museums, and became part of the Museum of Yugoslavia’s collection too.6 But still, when we met Prota in Belgrade, he was giving away these coupons to us as souvenirs. It was a generous gesture, which further made me think over the idea of artistic autonomy and ownership in your work.

P: This comes from our belief in communism, that art and education should be accessible to anyone. As Škart we decided from the very beginning that all we produce will be distributed for free; because distribution is endless.

S: Another note to add about the distribution of Coupons is that you were indeed invited by various arts and cultural institutions or festivals to present this project. How did you display them? Always through street actions? In Belgrade, for example, you were also travelling to small villages and getting in direct contact with people, distributing them on the streets. And once invited outside of the region, you developed a strategy to adapt multiple languages to every host country.

Ž: Coupons were originally in Serbian and English. After, we introduced them in German when we were invited to Graz by Steirischer Herbst in 1998.

P: In Graz we even built a fake machine to distribute coupons on the streets again; it was a wooden box and our friend hid inside. We were walking around the street and our invisible friend was distributing these coupons to passersby.

Ž: Then we were invited to Sweden, so we introduced Swedish coupons. In New York we chose the five most common languages in the city: English, Spanish, Chinese, Russian and Arabic.

P: It costs to publish, and thanks to these invitations we covered the costs of production, then we distributed them locally and internationally wherever we went. We also continued to send them around by post mail, worldwide, to some people, or the magazines that interested us.

Škart wishes you a nice day, 1990, silk screen print on paper, stamped, 34.9 × 49.7 cm.