The "Refugee Crisis" and the Current Predicament of the Liberal State

In collaboration with Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF), the organization SOS Méditerranée rescues refugees in distress off the Libyan coast. The photographer accompanied the NGOs and documented the rescue missions in the sea and the life on board the Aquarius, December 2016. Photo: Laurin Schmid.

Last year, two democratic decisions – the results of the Brexit referendum and of the presidential elections in the United States – reminded us how racial and cultural difference sit at the core of nationalist discourses and programmes. That these have taken place in the midst of this recent "refugee crisis," and used it to rekindle white supremacist desires, further confirm the need to attend to how raciality consistently checks universalist figures, such as that of the human being, the law, the liberal state. Focusing on the in/distinction between refugee protection and border protection, I find that raciality accounts for why those displaced by wars of global capital do not really move out of what I call the zone of violence (Ferreira da Silva 2009).

Following the European responses to the most recent "refugee crisis" in person and in the media, it is difficult to miss familiar terms and expressions that indicate how the racial is the most important political concept in the global present. Neither the "welcomes" from German and British authorities, nor crucial commentary by the ubiquitous contemporary leftist European philosopher Slavoj Žižek disguise the inability of Europeans to comprehend that they have produced the circumstances forcing millions out of their homes, to risk their lives crossing the dangerous Mediterranean waters and unfriendly lands in Eastern and Southern Europe. For it is not only that Western Europe, the United States, and their global business partners are responsible for, with or without military presence– in Iraq, Syria, Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Libya, and the urban and rural warfare that prevails in economically dispossessed places in Latin America, the Caribbean, and the United States. They are part of the juridical assemblage that facilitates global capital's (that is, state capital) access to productive resources – bodies and territories. What sustains this assemblage is the figure of the human being who, much like the notion of the nation for most of the twentieth century, governs global (state) capital ethical text. My argument here is that today the racial figure of the human being plays the same ethical role for global capital that the notion of the nation played for industrial-state / empire-capital for most of the twentieth century. It allows the demarcation of whom falls on either side of the law, namely the protective and the punitive. Put differently, law enforcement – in the form of the war on terror, the war on drugs, and border protection – has become global capital's most effective political strategy. Why is it that contemporary political theorists and philosophers have so little to say about it? Why don't critiques of state capital, of global capital, tackle this? I have a hunch: we need to expand our political imagination. At work in these strategies, the operative moment in global subjugation is the ethical grammar of raciality, which foregrounds the human being as a physical and cultural entity, establishes very distinct ethico-juridical subjects, a distinction that manifests in how they fare before the law. The problem however is that raciality also informs the political discourse of the contemporary left.

I would like to comment on Slavoj Žižek's blog and the two prescriptive statements he made about how refugees should be welcomed in Europe: (a) They should assimilate to the European way of life and (b) they should follow strict rules and regulations (Žižek 2015, Ferreira da Silva 2016). The second determination, as we know, is already in place, in the framework of refugee protection, which is part of the Human Rights framework and International Law. The legal framework for refugee protection includes three main documents: the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugee, in the aftermath of the Second World War, with the still prevailing rationale that "states have the responsibility to protect their citizens" and when it cannot do so, the international community steps in "to protect those basic rights of refugees"; then the Organization of African Unity (OAU) Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa; and the 1984 Cartagena Declaration, covering the situation of Latin American refugees. Basically, the "proper" refugee is someone who, in the 1951 Convention has a well-founded fear of persecution because of his/her race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or, political opinion; who is outside his/her country of origin; and who is unable or unwilling to avail him/herself of the protection of that country, or to return there, for fear of persecution. In the 1969 OAU convention, any person compelled to leave his/her country owing to external aggression, occupation, foreign domination or events seriously disturbing public order in either part or the whole of his country of origin or nationality. The 1984 Cartagena Declaration adds persons who flee their countries "because their lives, safety or freedom have been threatened by generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violation of human rights or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed public order". As any legal documents, the refugee protection framework establishes a negative right: the right not to be returned or the right to stay. Towards meeting this international legal obligation, to protect the right to stay, states – and multilateral entities such as the EU – set up juridical structures of law enforcement and management that have increasingly focused, over the years and in particular since 9/11, on keeping refugees away. This has includes outsourcing asylum seekers to neighbouring countries or keeping them in detention centres.

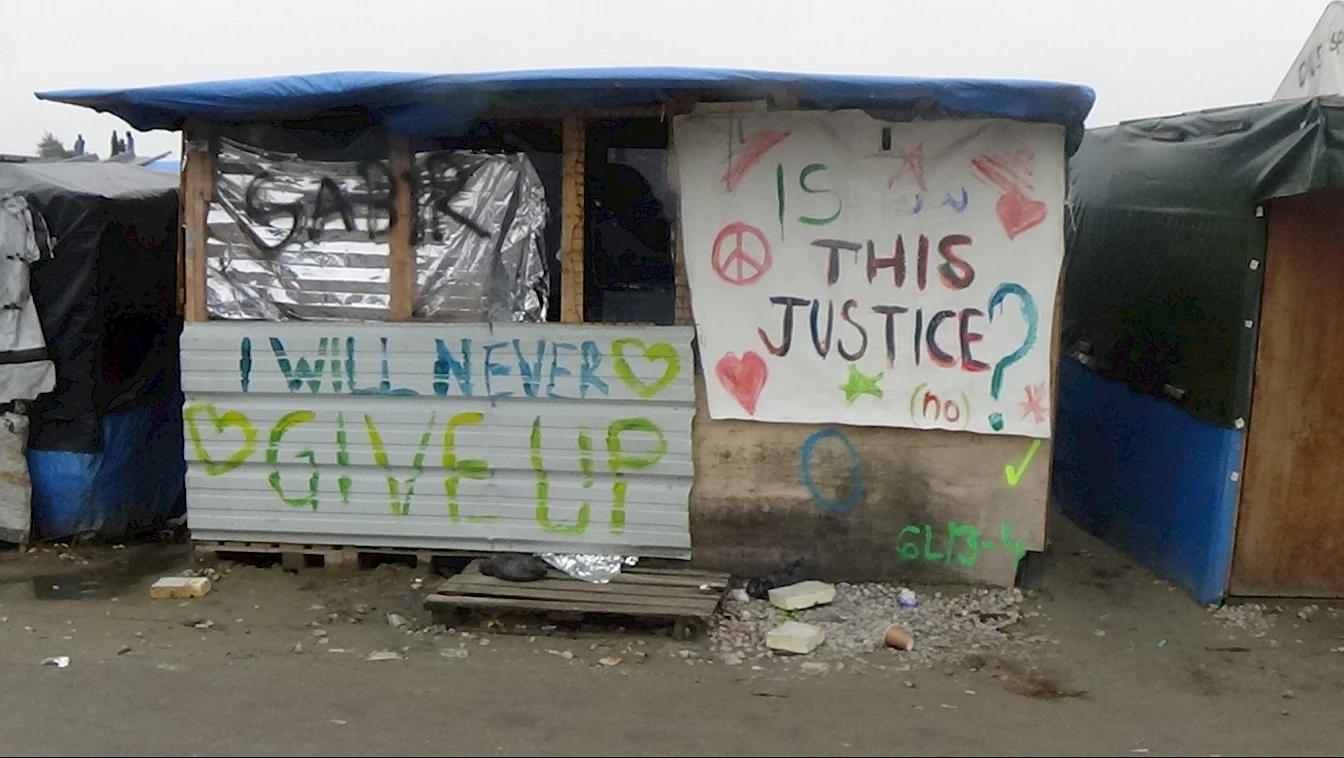

Picture taken just before the evacuation and demolition of the migrant camp near Calais. Photo: Nicola Scotto, Meltingpot.

Not surprisingly, the European Union announced its response to the "refugee crisis" of 2015, with the release of the European Agenda on Migration – a migration management programme which releases extra financial and other resources to be allocated to border enforcement in Europe, the neighbouring countries in North Africa, and the places of origins of the refugees. When reading the document, it is difficult to miss the in/distinction between refugee protection and border protection. Virtually all measures announced to welcome refugees are designed to protect Europe: the president of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, introduced the measures by saying:

In spite of our fragility, our self-perceived weaknesses, today it is Europe that is sought as a place of refuge and exile. This is something to be proud of, though it is not without its challenges. The first priority today is and must be addressing the refugee crisis. The decision to relocate 160,000 people from the most affected Member States is a historic first and a genuine, laudable expression of European solidarity. It cannot be the end of the story, however. It is time for further, bold, determined and concerted action by the European Union, by its institutions and by all its Member States.1

To be sure, this is so because of the operation of something that is implicit in Žižek's first prescription – that refugees assimilate to European way of life. It is precisely the ideology of global capital which he has denounced on many occasions that plays a crucial role in his analysis of the refugee crisis – as a sort of intellectual trauma without which his speech would make no sense.

What we find in the global present, in the nationalist challenges to the liberal states that find excuses in the recent "refugee crisis", is how raciality (racial difference and cultural difference) function as an ethical device – which checked the universality attributed to the human being and law. It enables the collapse of the administration of justice into law enforcement (with distinct levels of lethality) – when its tools are deployed to write the global/ racial subaltern as an affectable I, or as a modern subject that thrives in violence. That is, because they construct the racial subaltern's bodies and territories as signifiers of violence. The tools of raciality effectively justify deployments of both total violence and law enforcement, under the guise of protecting measures, but which work under the state mandate for self-preservation (Ferreira da Silva 2009).

If raciality informs both the nationalist trend now threatening to occupy the liberal state and the political discourse of the left, whence will a critique of global capital be available to challenge both?

References:

Ferreira da Silva, D. 2009, "No-bodies: Law, Raciality and Violence", Griffith Law Review, vol. 18, no. 2, August, pp. 212–236.

Ferreira da Silva, D. 2016, "Fractal Thinking", aCCeSsions, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, New York, 27 April, viewed 8 March 2017.

Žižek, S. 2015, "We Can't Address the EU Refugee Crisis Without Confronting Global Capitalism", In These Times, September 9, viewed 8 March 2017.