The Vagaries of the Expression "Civil Society": The Yugoslav Alternative

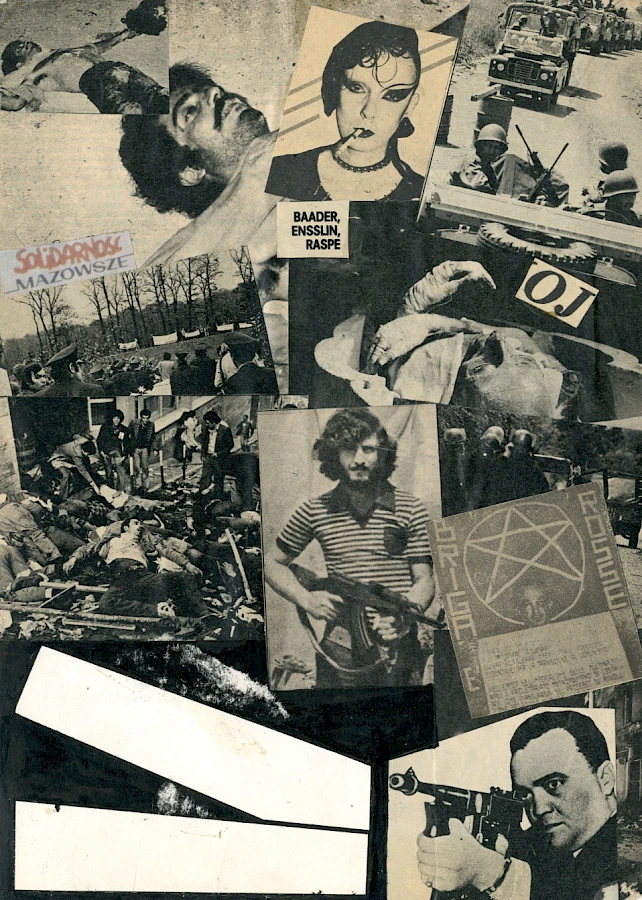

Marin Rosić, Draft for the poster of Disco FV, 1983/1984. Courtesy: the author.

Civil society was a slogan of anti-communist movements in the European Real Socialism of the Soviet bloc and, later, it was also the most important "alternative" ideology at the beginning of the reconstruction of capitalism in those countries. In terms of ideology, this "alternative" – at least the most vocal fractions in the countries of the former Soviet bloc – was liberal-democratic: it contended for the consequent realisation of the ideology in the name of which capitalism was being reconstructed. Thus it stood for an idealised image of capitalism, which is in stark contrast to the everyday reality of neoliberal capitalism and, in particular, its post-socialist peripheral type. Despite what were probably good intentions, this "alternative" helped introduce capitalism to former socialist countries: it maintained the illusion that a democratic and working-people-friendly "capitalism with a human face" is possible.

The "civil-society illusion" continues; in post-socialist countries it has even become part of the rulers' ideology. Now it is not only employed as an ideological mystification and legitimisation of the new order. It is used in endeavours to create something that could be called "class awareness" of the ruling post-socialist groups which, however, cannot arrange themselves into a genuine ruling class. The post-socialist ruling coalitions in the former Soviet satellites, and in the fragments of the Yugoslav federation after they "gained independence", are not productive capitalist classes striving for surplus value by means of technological and organisational revolution, thus using their "egoist" interests to form a general rate of profit, and thereby assuring a capitalist class structure. On the contrary, the new ruling groups are either parasitic "tycoons" who have their capital as a source of annuity and a token for speculation, or comprador bourgeoisies who collect annuities from their work for transnational capital. These trust-funders cannot compose themselves into a real ruling class, since they are guided merely by selfish benefits without connective effects. Their group solidarity could only be instigated by a revolt of labour, or the pressure of transnational capital and its institutional representatives (International Monetary Fund, World Bank, etc.) or political representatives (European Union, US government, etc.). The moralistic actions of "civil society" are an ideological supplement and cosmetic varnishing of the economic, political and military pressures of transnational capital.

In the past, however, practices regulated by the ideology of "civil society" triggered direct and dramatic historical transformations. We could even say that the only practical demonstration of Antonio Gramsci's theoretical concept of "civil society" occurred precisely in socialist Europe. But the practice of civil society functioned in a perverted sense: it did not lead to socialist revolution in the centre of the capitalist system, as anticipated by Gramsci, but rather helped the capitalist counter-revolution on the socialist semi-periphery.

With his concept of civil society, Gramsci intended to explain why socialist revolution did not happen in the developed capitalist West. In Russia, he wrote, the civil society was "jellied", that is, shapeless and unformed. The revolution in Russia could therefore win simply by conquering the state. In the developed capitalist West, the takeover of state rule would certainly not suffice. In the centre of the capitalist system stand real strongholds of class domination – relative to them, the state is merely a kind of front line of defence. According to Gramsci, a revolutionary party within the capitalist system must therefore produce a strategy that differs from the one practised by the Bolsheviks in Russia. The revolutionaries in Russia took over state control in a sudden assault, or "manoeuvre warfare", and then they started to use state and party apparatuses to remake civil society into a socialist society. Or, this is how they were meant to act according to Gramsci's conceptions. He considered that in the West, i.e. in the centre of the system, the main battlefield of class struggle is within civil society: in the sphere of culture and social organisations, in the field of everyday life, revolutionaries were supposed to start a patient and long-lasting effort which would finally ensure "hegemony" for the socialist project. Gramsci compared this endeavour for prevalence of civil society with "war of position".

In Gramsci's theory, ideological / political work in civil society was indispensable, since the state was only one of the apparatuses of bourgeois rule – and since the state was not even the most important bastion of this rule. In the practice of the Eastern European freedom fighters, civil society was the only possible arena for action since the state was too strong. Especially in Poland, but to a lesser degree in other countries of "administrative socialism", autonomous organisations (trade unions) and civil movements actually secured hegemony in civil society and "besieged" the etatist state. Without support in society, the state/ party apparatus inevitably broke – and in an instant, as it were, the neoliberal restoration of capitalism set in.

In Yugoslavia, these processes occurred differently from the Soviet bloc. An alternative was shaped within Yugoslav socialism that did not refer to "civil society", at least not at the beginning. The Yugoslav alternative was a conglomerate of counter-system movements with ideological sources in pluralistic traditions of global leftist and revolutionary movements.

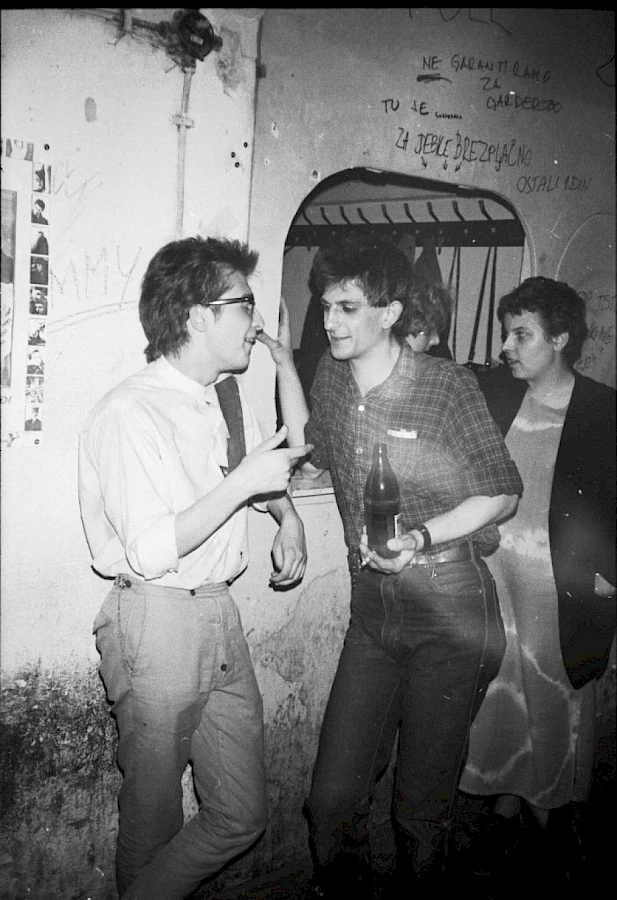

Marin Rosić, Punk Tank (Tivoli parc, Ljubljana), 1982, photo. Courtesy: the author.

Alternative politics in socialist Yugoslavia was on the left or, more precisely, left-wing. It had problems with the concept of civil society, since it was only familiar with two variants: Karl Marx's and Gramsci's. For Marx, civil society was a residual category: he saw it as something which is left after the bourgeois political sphere constitutes itself into an autonomous sphere of abstract and illusory freedom and equality. The establishment of a political state instigates a decomposition of the "citizen's society" into autonomous selfish individuals bound only by legal formalism. Marx's notion of "civil society" is negative, while Gramsci's concept appeared archaic in the context of Yugoslav socialism – at least as an alternative: in self-management socialism with its project of abolition of the state, it would not be very "alternative" to impose "civil society" in contrast to the state. The Yugoslav alternative strove for the establishment of "different spaces of sociality". Therefore it could not enclose itself in the opposition "society against the state" (which was actually the official ideology); rather, it wanted to open new forms of sociality.

It was a particular feature of the Yugoslav alternative that it was composed of counter-system movements in a state which itself was counter-system. Socialist Yugoslavia was socialist, that is, anti-capitalist; it was self-managerial and, in its official ideology, it viewed itself explicitly as an alternative to historical etatist socialisms; finally, it was one of the leading countries in the Non-Aligned Movement, and was thus both opposed to the bloc system and asserting an alternative to that division of the world. What was, as it were, the ideal standpoint for overcoming capitalism according to the logic of Immanuel Wallerstein's analysis of world capitalism, had already been attained in Yugoslavia. In the 1980s, Yugoslavia had so to speak an ideal position to start developing historically innovative answers to the passing away of the capitalist world system and to search for positive alternatives.

Alternative movements in Yugoslavia started to refer to civil society relatively late. The Yugoslav alternative in effect imported the ideology of "civil society" from Eastern Europe. This term did not enter its vocabulary through Yugoslav theoretical debates, despite the fact that they were dealing with Gramsci's theory of civil society from at least the early 1960s, when it was systematically introduced into Yugoslav theory by Anton Žun. However, Žun and other Yugoslav theorists kept believing that Gramsci's theory of civil society was significant merely in the context of the fight for socialism within the developed capitalist world.

Then in the 1980s, social-science academics started to develop the theory of "socialist civil society". This theory did not trigger visible effects in wider public debates or in the political arena. It did however have an effect in political apparatuses, since it co-created the ideology of a more liberal part of the political bureaucracy, at least. The effects of the lesson on "socialist civil society" were contradictory: on the one hand, they accelerated democratisation, stimulated public articulation of social conflicts and accelerated the processes of de-etatisation and abolition of the party monopoly – in short, they asserted a number of positive goals of socialist ideology. On the other hand, they eliminated the class aspect of social tensions and conflicts, depoliticised public speech and, thus, strengthened technocratic tendencies within the political bureaucracy as well as nationalistic trends in the bureaucracy of ideological apparatuses of the state ("cultural" bureaucracy).

Alternative movements in Yugoslavia took over the ideology of civil society from the vocabulary of alternatives in other socialist countries, but also from the academic reflection about civil society in Eastern European socialism and in the English-speaking world. In the Yugoslav alternative context, the term "civil society" stood for establishing connections between different alternative social movements, but it also displayed an orientation towards the "people's front" and was historically associated with anti-fascist people's fronts.

Before we started speaking about "civil society" – but also later – we were using other terms: "alternative movements", the "alternative", and "new social movements". These terms sought to emphasise that such political activities and such movements are not an "opposition" to the existing authorities, that they are not after the takeover of power – rather, that they are opening up, as we used to say, "different spaces of sociality". Alternative movements included a number of "single-issue movements", as they were called at the time: they were organised around one single topic and did not deal with wider ideological problems. Such cases in point were the movement against school reform in the early 1980s, movement against the death penalty, and movement for the recognition of conscientious objection to performing armed military service.

Some alternatives had wider and more complex platforms: feminism was active primarily in theoretical and political spheres; the ecological and peace movements were also political. One of the characteristics of Yugoslav alternatives was strong lesbian and gay scenes. They succeeded in creating a specific subculture, but they also operated in the field of theory. The then homophobic political establishment endeavoured to discredit gay activism by frightening the public with the danger of AIDS. So it is precisely the gay movements that merit the historical credit for organising the first debates intended for the wider public about the nature of this illness and its prevention.

Matija Praznik, Disco FV, 1982, photo. Courtesy: the author.

In the 1980s, the Yugoslav alternative launched significant battles regarding the right of expression (Article 133 of the Federal Penal Code, which criminalised "verbal delict") and other human rights (especially in connection with the Belgrade trial against the organisers of the Free University in 1984-5). Henceforth, the term "civil society" started to be associated with struggling for human rights and the rule of law. It was self-evident for many participants that we were striving for human rights within the framework of the socialist state. For us it seemed obvious that human rights remain an empty form and legal verbalism, if economic and social equality of people is not assured. Definitely there was no one at that time prepared to stand publicly for the thesis that became part of the ruling ideology in the time of the reconstruction of capitalism: namely, that private property of the means of production was a precondition for a "real" democracy.

In Slovenia, freedom of public expression was actually won in the first half of the 1980s. "Alternative reporting" was winning recognition in a number of editorial offices at the time, quickly widening the space of public expression and increasing the quality of the media. The final breakthrough resulted from a judgement stating (albeit with considerable delay) that the editorial board of the Delo newspaper unduly refused to publish several readers' letters about school reform. The "long march" through judicial instances that led to the verdict was conducted by Matevž Krivic. It was crucial for the freedom of expression at the time that the media were in social ownership. Therefore they were bound by the constitution to publish information and opinions that were important for the public. In the wake of Matevž Krivic's successful confirmation of this constitutional right in court, editorial boards could refuse an article only if they proved that it was not important for the public – and therefore, in general, they stopped refusing articles.

The second crucial act in the fight for freedom of expression was a conclusion of the Honorary Court of Arbitration of the Slovene Association of Journalists, stating that an article prejudiced the guilt of the accused in the Belgrade trial (1984-5) and declared that it was counter to journalistic ethics. Yet on the other hand we should point out the contradiction of the then trial: on the basis of the disputed Article 133 of the Federal Penal Code ("hostile propaganda"), three of the six accused in the Belgrade trial were sentenced in February 1985 to one or two years in prison.

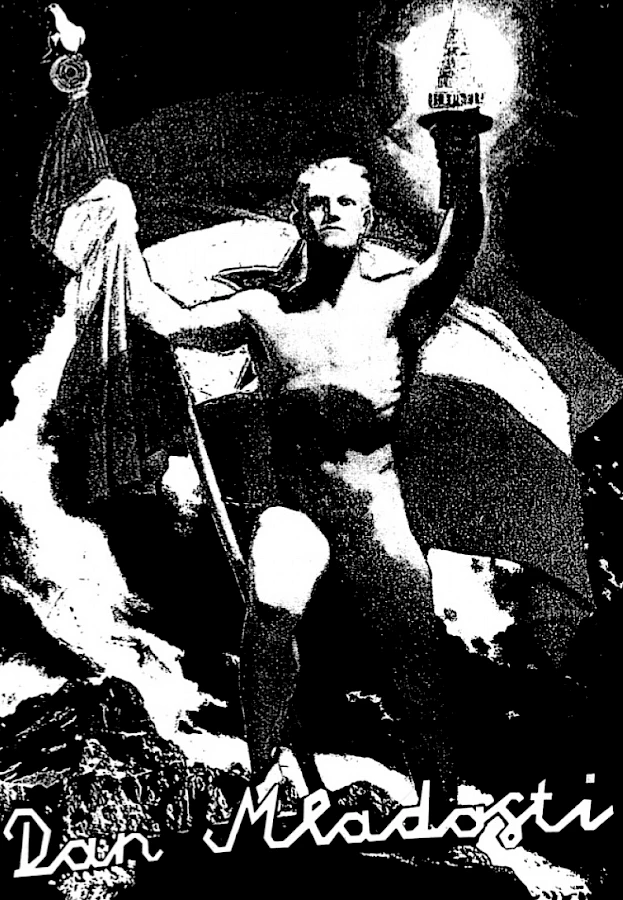

New Collectivism, Day of Youth, 1987, poster.

In the Yugoslav alternative, "civil society" was not much more than merely a political slogan. The point is that Yugoslav self-management socialism itself was counter-etatist: its political goal was to abolish the state and directly organise society in such a manner that "pluralism of self-managerial interests" could gain ground in its institutions. Certainly we could discuss the scale of the actual realisation of the programme, the degree to which institutions of the system did actually implement it, and so on; however, asserting "civil society" against "the state" would represent nothing "alternative" within the political horizon set by the institutions of the system.

When the ruling coalition of political and ideological ("cultural") bureaucracies rearticulated itself in the late 1980s on nationalistic foundations (and, as happened often at that time, the economic or managerial ruling group was modelled on the political bureaucracy), this act was instigated in part by the apolitical effects of the ideology of "civil society", among other factors. The foundation of a new type of state on a nationalist basis that advertised itself as "apolitical" and with a "civil societal" ideology, provided the ground for a class (and therefore political) act par excellence: the reconstruction of capitalism. Tomaž Mastnak wrote at that time that civil society took the power. Even earlier, some of us wrote about "fascism". A little later, Tonči Kuzmanić proposed the term "post-fascism", pointing to the historical novelty of this new politics.

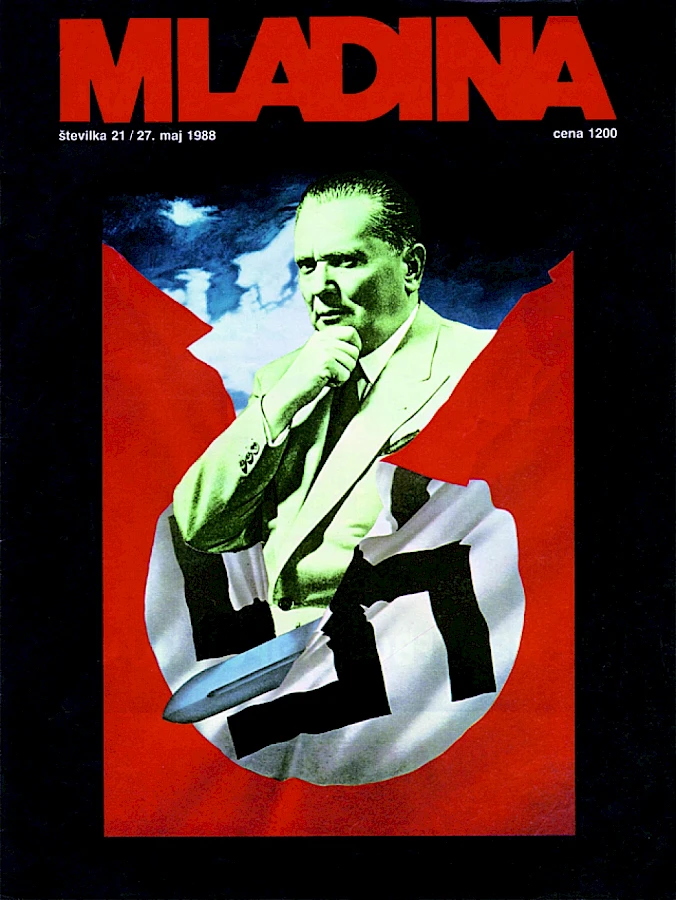

New Collectivism, cover of the magazine Mladina, 1988.

At the beginning of the reconstruction of capitalism, the term "civil society" in our country signified the "second alternative" to which the alternative political and cultural practices of the time resorted. It was a conglomerate of practices, movements and institutions, a result of rearticulation of the former socialist "first alternative" under the pressure of new capitalist rule. In the 1990s, "civil society" thus represented a self-organisation of cultural and political practices which were opposed to the logic of the identity of the peripheral capitalist state, and which continued to create spaces of different socialities.

It seems, however, that the ideology of "civil society" is currently becoming one of the elements in the rulers' ideology: when party or "supra-party" politicians complain – more or less hypocritically – about the rottenness or non-representativeness of the party establishment, and moan about the greed of the new bureaucracy, they usually and ritually call "civil society" for help. But in the current language of political and ideological apparatuses of the capitalist state, "civil society" is more or less an empty cliché.

It seems that the theoretical concept of "civil society" has now drowned in the history of theory. And what used to be an explosive ideological charge of the term, which instigated contradictory and even antagonistic historical consequences, has finally emptied itself into a jargonistic filler of verbiage by comprador-like political castes of post-socialist capitalism.

Bibliography

Dobnikar, M. (ur.). 1985, O ženski in ženskem gibanju, KRT, Ljubljana.

Kuzmanić, T. 1988, Strikes - the Beginning of the End (of Self-Management), KRT, Ljubljana.

Lešnik, A. (ur.). 2014, Anton Žun: Sociologija prava – Sociologija – Politična sociologija, Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete, Ljubljana.

Lovšin, P., Mlakar, P. in Vidmar, I. (ur.). 2002, Punk je bil prej: 25 let punka pod Slovenci, Cankarjeva založba in ROPOT, Ljubljana.

Malečkar, N. in Mastnak, T. (ur.). 1985, Punk pod Slovenci (Punk under the Slovenians), Krt, Ljubljana.

Mastnak, T. 1992, Vzhodno od raja: civilna družba pod komunizmom in po njem, Državna založba Slovenije, Ljubljana.

Močnik, R. 2003, 3 teorije. Ideologija, nacija, institucija, Centar za savremenu umetnost, Beograd.

Močnik, R. 2003, Teorija za politiko, Založba /*cf., Ljubljana.

Močnik, R. 2008, "Regulation of the particular and its socio-political effects", in: Tarabout, G. and Samaddar, R. (ed.). Conflict, Power, and the Landscape of Constitutionalism, Routledge: London – New York – New Delhi, pp.182 – 209.

Štrajn, D. 1987, "Nekaj smernic za idejno-politično razumevanje AIDSA"; RAZPOL 3 - PROBLEMI 9, vol.10.

Tratnik, S. in Segan, N.S. (ur.). 1996, L, zbornik o lezbičnem gibanju na Slovenskem, 1984-1995, ŠKUC-Lambda, Ljubljana.

Translated by Borut Cajnko