Across Mangelos’s Landscape

In her essay art historian Leonida Kovač revisits the work of Mangelos, the alter ego of Dimitrije Bašičević, longtime curator of Zagreb City Galleries and what was to become the museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb (MSU). As Kovač writes Mangelos ‘generated a multidimensional field in which artistic production interfered with a completely noncanonical, performative art-writing practice’. The essay is accompanied by extensive images of Mangelos’s artist’s books and works, coming from private and public collections, as well as the collection of L’Internationale partner MSU.

In June 2011, twenty-four years after Mangelos’s death,1 art historian and philosopher Georges Didi-Huberman visited the site where the Auschwitz-Birkenau Nazi extermination camp had been in operation from 1940 to 1945. In July of the same year, he wrote a text entitled Bark and published it in the form of a book that also contained several black-and-white photographs he had personally taken in the landscape of death. The text begins as follows:

I placed three small pieces of bark on a sheet of paper and looked. I looked, with the idea that looking would perhaps help me to read something that had never been written. I looked upon the three small strips of bark as the three letters of a script preceding all alphabets. Or perhaps as the beginning of a letter – but to whom? I notice that I’ve spontaneously arranged them on the blank paper in the direction of my written language. Each ‘letter’ starts on the left, where I dug my nails into the tree trunk to strip the bark away.2

The bark was stripped away from a birch, a tree after whose name in German, Birke, the landscape of death in southern Poland had been named. In its format, Didi-Huberman’s Bark is reminiscent of numerous works made by Mangelos between 1949 and his death in 1987, which today are referred to by the generic term ‘artist’s book’.

In his 1990 book Devant l’image, translated into English as Confronting Images (and groundbreaking within the discipline of art history), Didi-Huberman questioned ‘the tone of certainty that prevails so often in the beautiful discipline of the history of art’.3 He asked:

What obscure or triumphant reasons, what morbid anxieties or maniacal exaltations can have brought the history of art to adopt such a tone, such a rhetoric of certainty? How did such a closure of the visible onto the legible and of all this onto intelligible knowledge manage – and with such seeming self-evidence – to constitute itself? … In short, the said ‘specific knowledge of art’ ended up imposing its own specific form of discourse on its object, at the risk of inventing artificial boundaries for its object – an object dispossessed of its own specific deployment or unfolding. So the seeming self-evidence and the tone of certainty that this knowledge imposes are understandable: all it looks for in art are answers that are already given by its discursive problematic.4

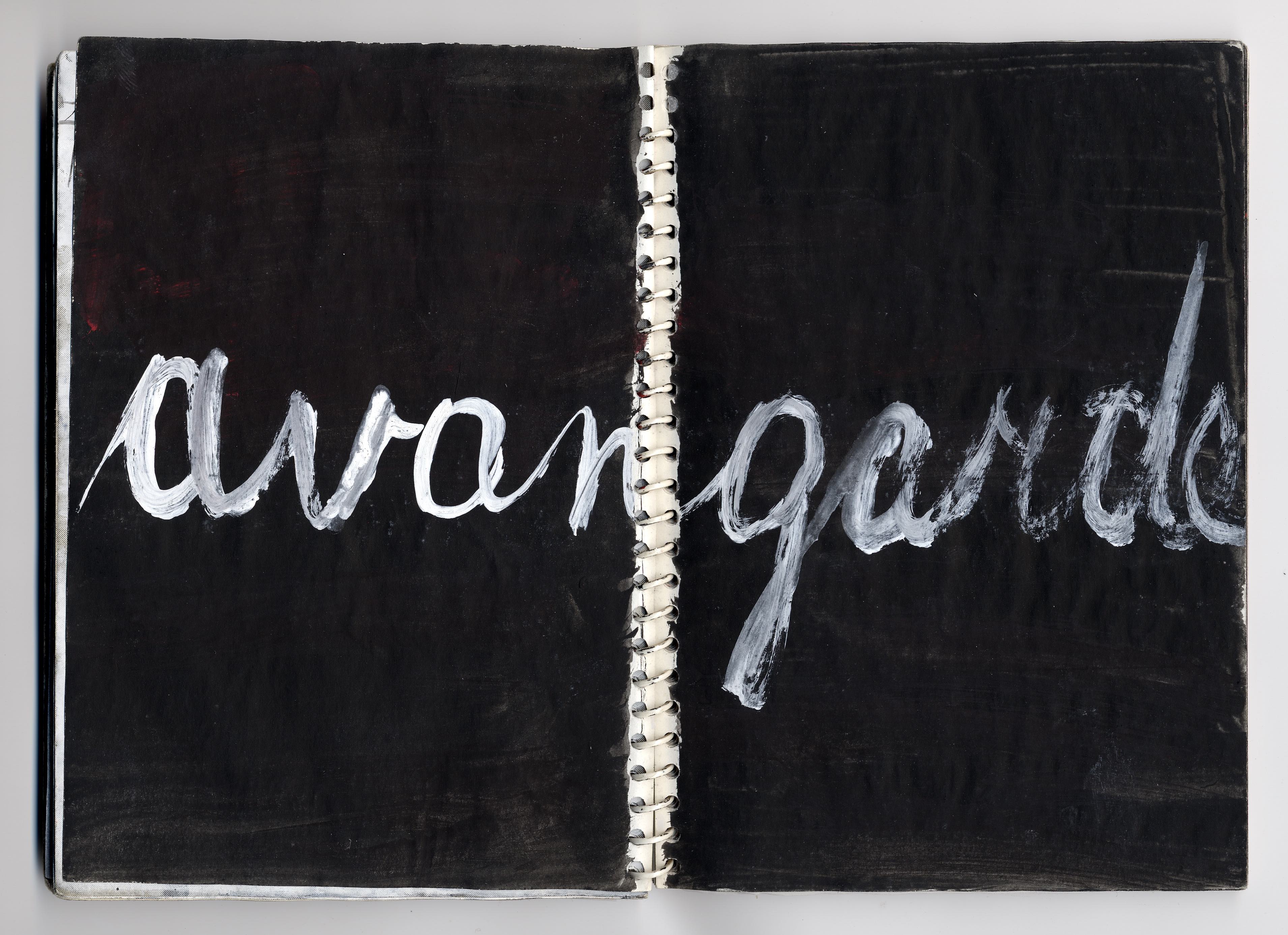

Dimitrije Bašičević, an art historian by education whose alter ego was the artist Mangelos, not only abolished in his work the imaginary boundaries of the objects of ‘kunsthistorical’ interest,5 but above all generated a multidimensional field in which artistic production interfered with a completely noncanonical, performative art-writing practice. A longtime curator of the Zagreb City Galleries, later to become today’s Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, Bašičević was also one of the most lucid theorists and critics of visual arts in former Yugoslavia, whose own resistant scepticism regarding the ‘specific knowledge of art’ and its hegemonic discourse, with its tone of self-evidence and self-sufficiency, was not only the reason why, in 1955, the Croatian Association of Visual Artists published a pamphlet demanding a ban on the public activity of the then-young critic Bašičević, but also the groundwork for Mangelos’s noart.6

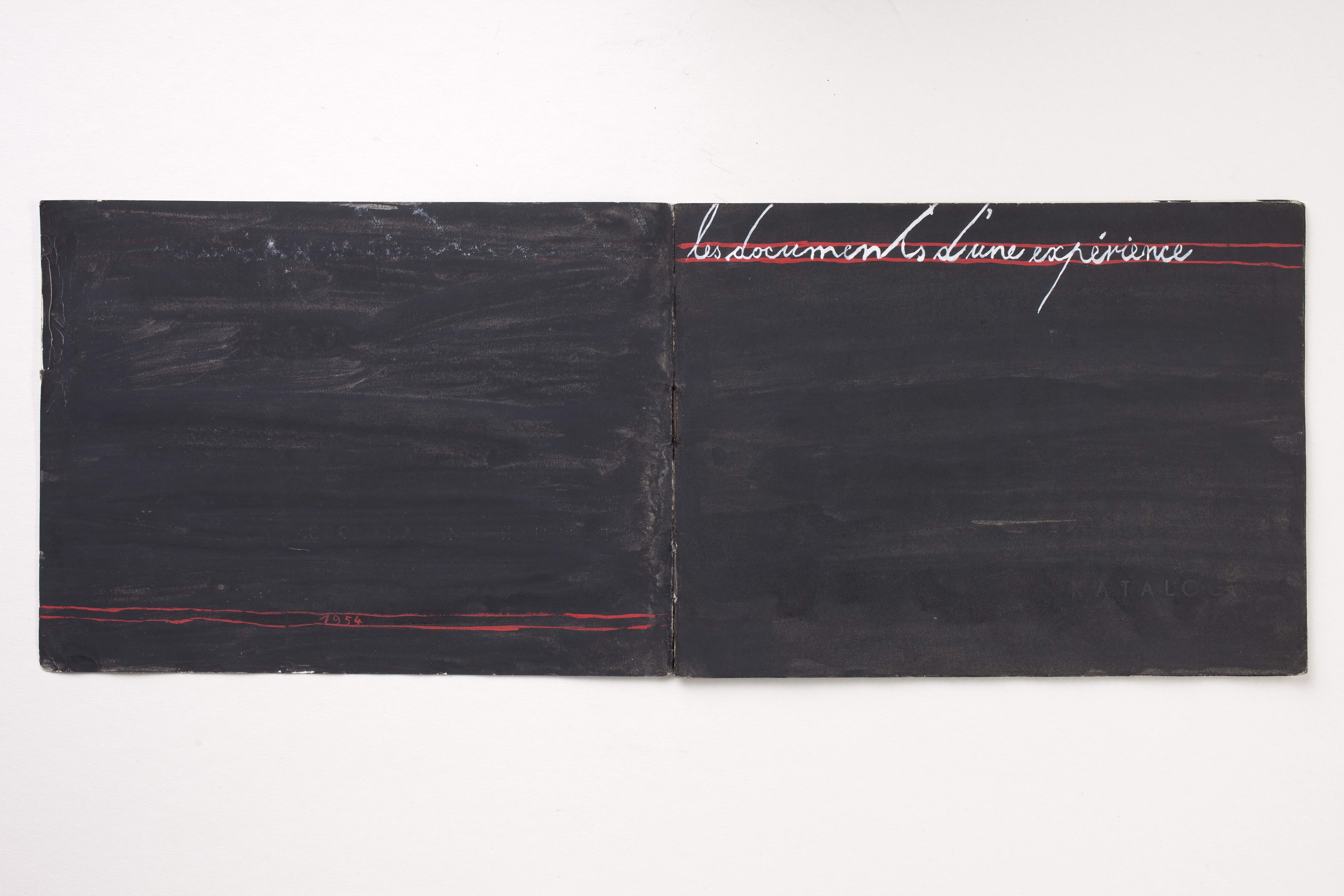

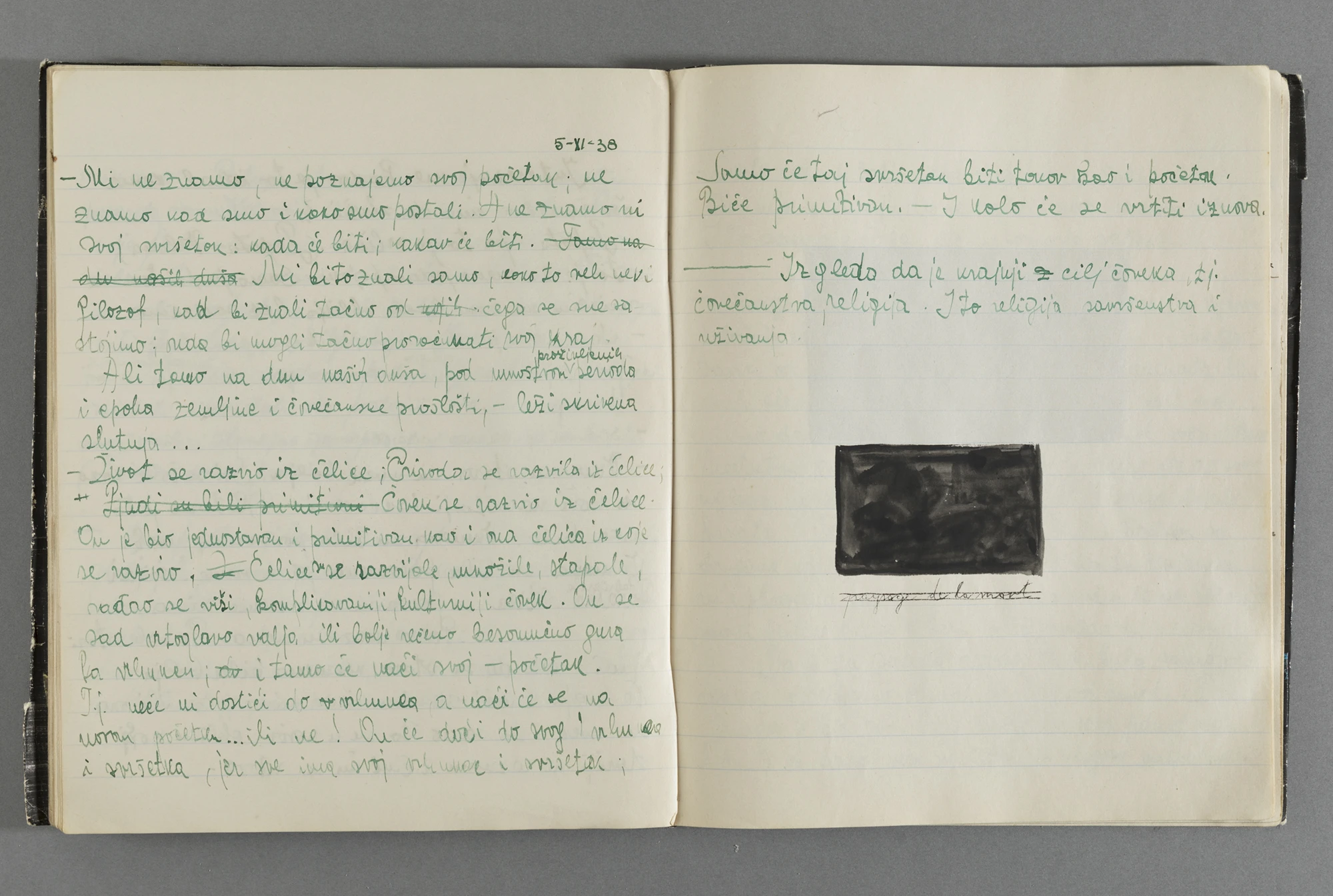

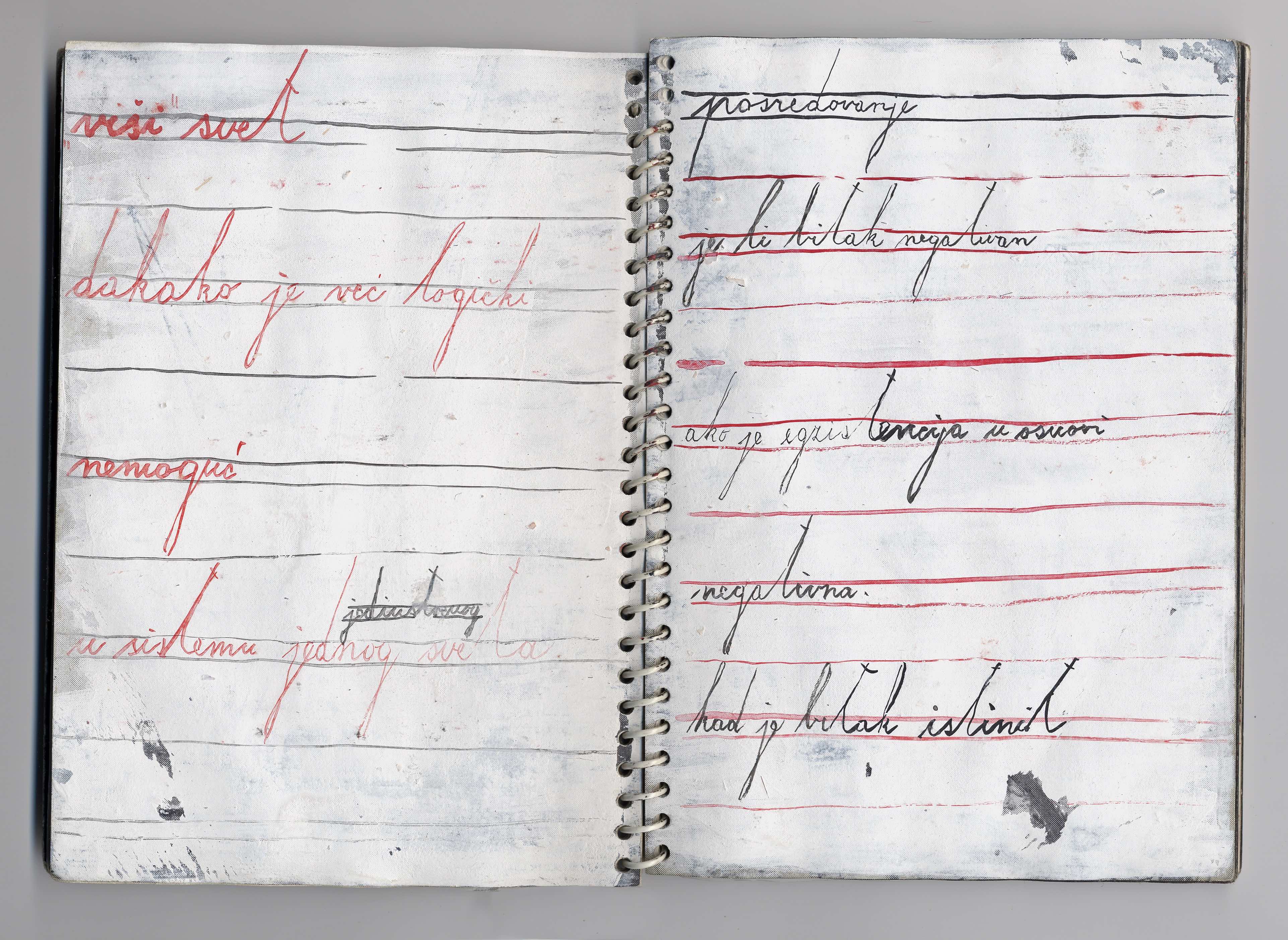

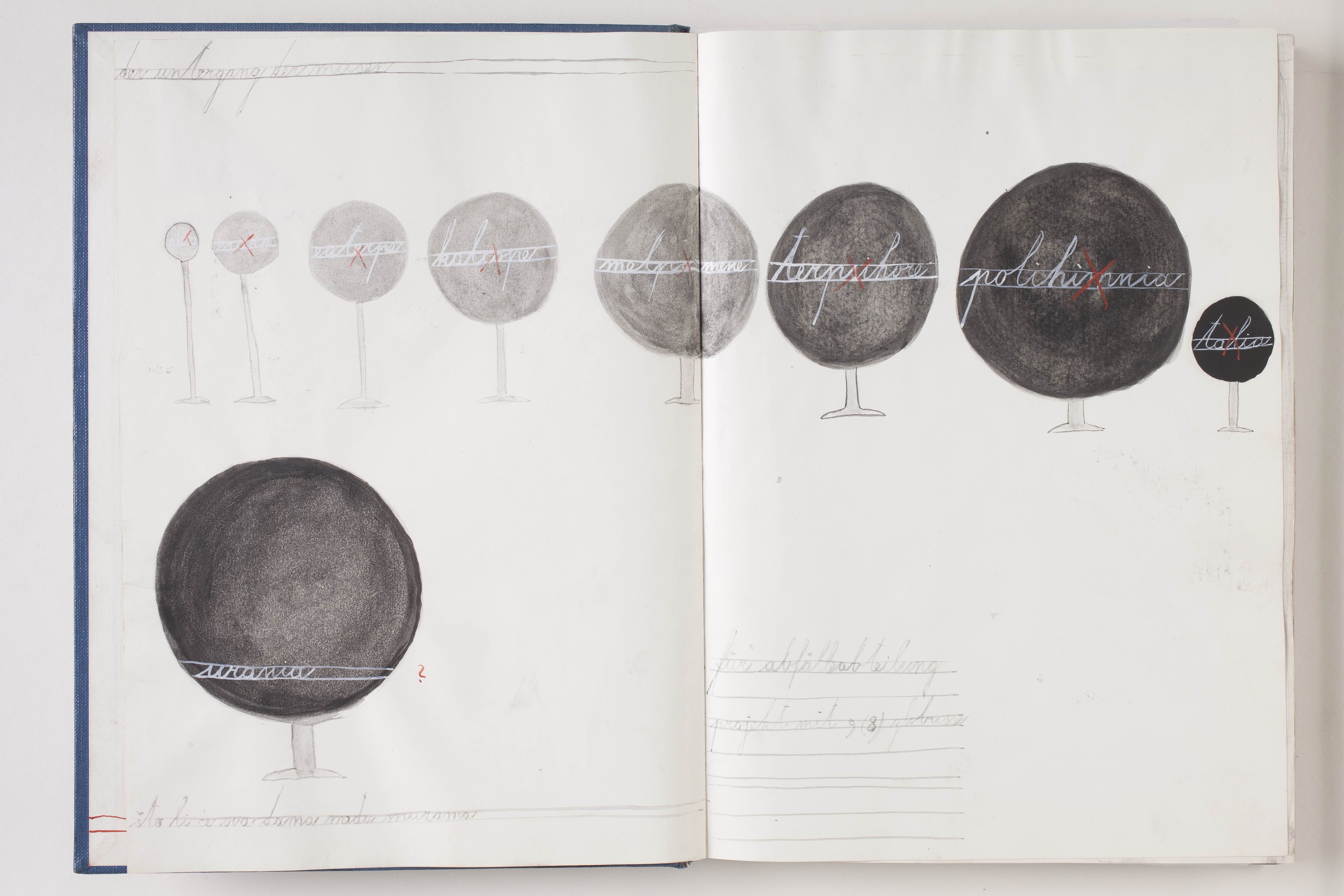

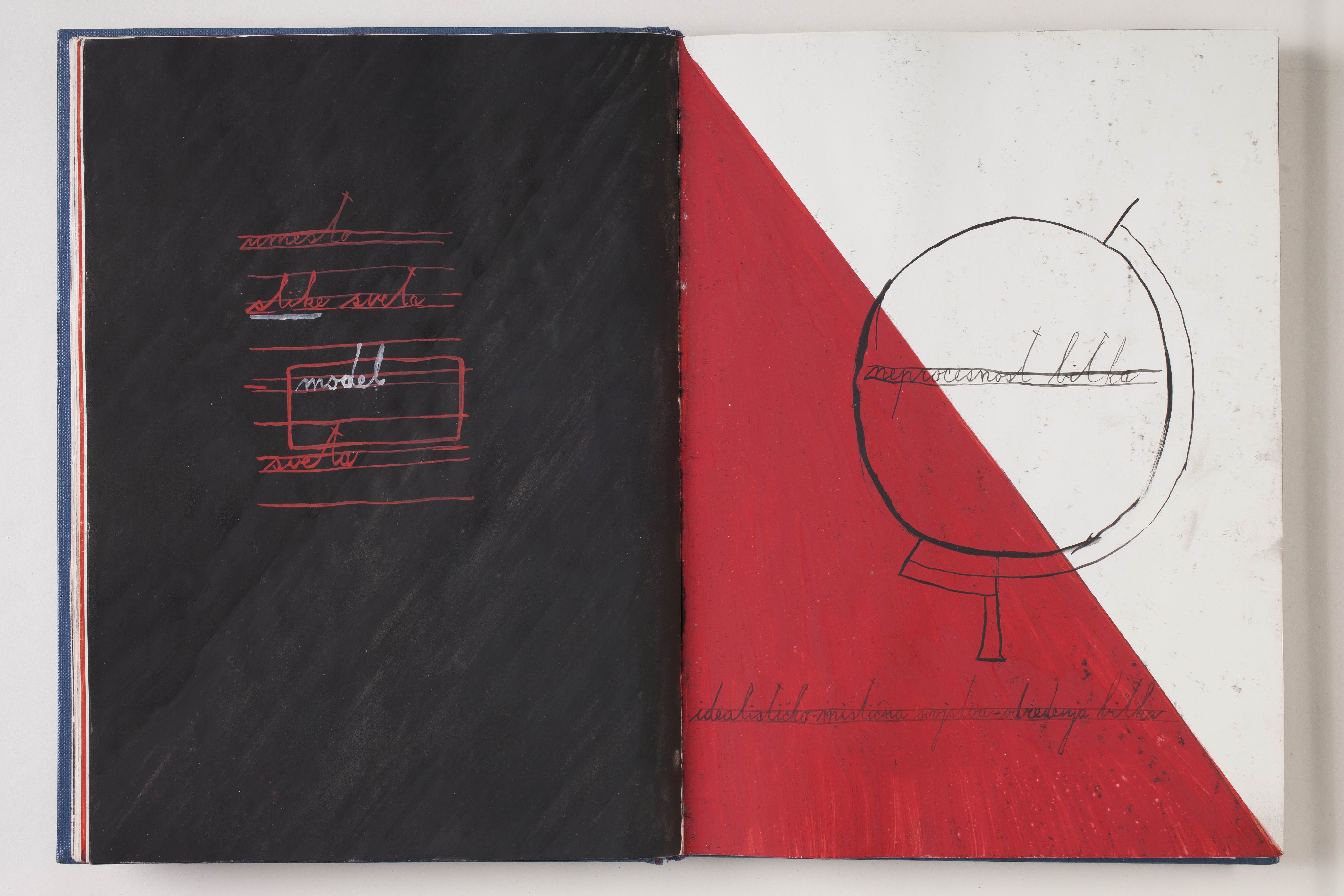

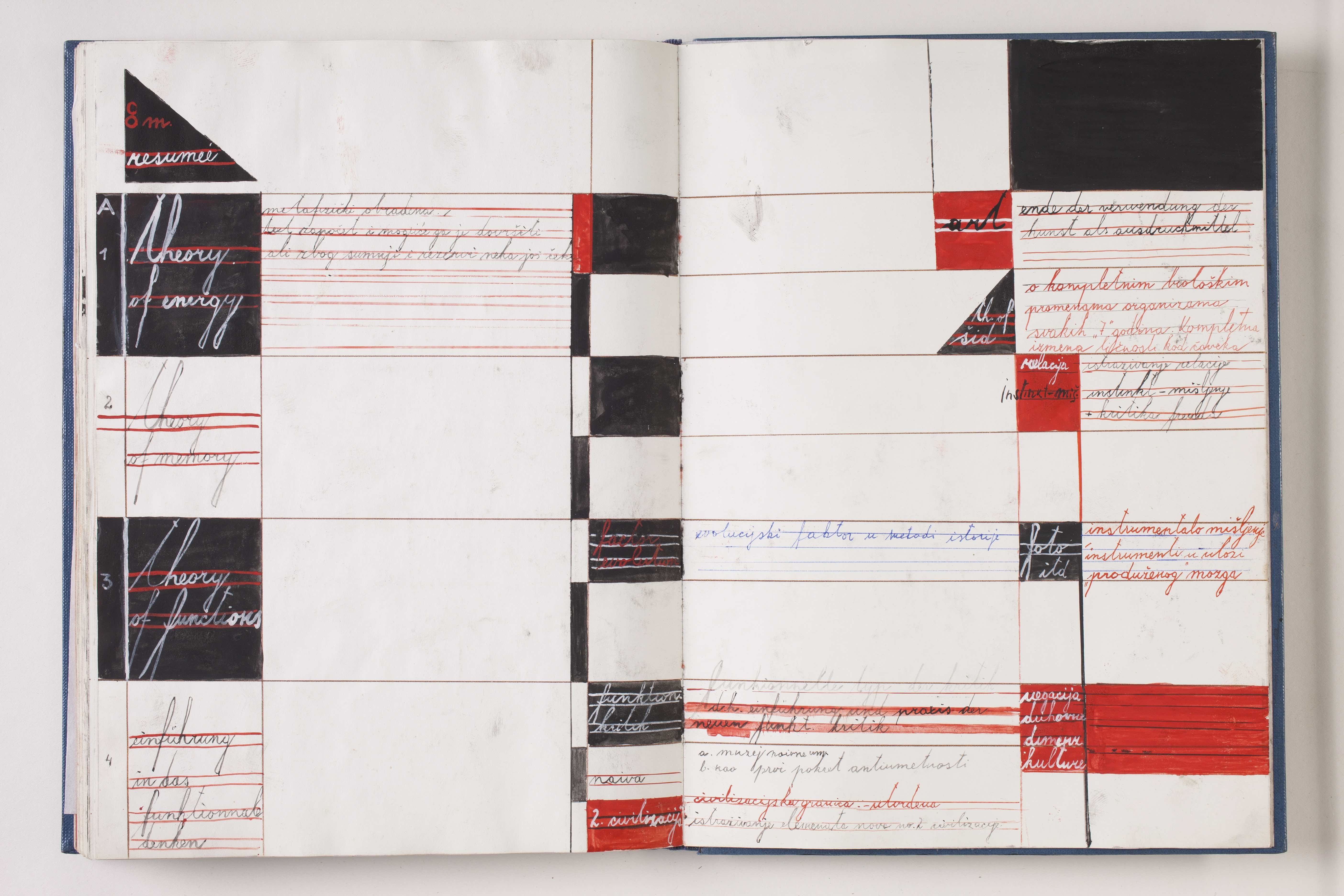

Dimitrije Bašičević Mangelos: Documents d'un éxperiment, artist book, 1954, courtesy of Mario Bruketa

Mangelos’s self-denying artistic activity, which, while barely presented to the public during his lifetime, has attracted considerable attention on the international contemporary art scene over the past two decades and is increasingly the subject of curatorial and academic interest, mainly due to many years of systematic research, publication and exhibition by the art historian and curator Branka Stipančić.7 In the scholarly literature on Mangelos, biographical data are scanty. One learns that he was born in 1921 into a family of farmers in the Syrmian town of Šid, and that he attended high school in Sremska Mitrovica and Sremski Karlovci. After the establishment in 1941, under the tutelage of Nazi Germany and fascist Italy, of the Ustasha regime and the Independent State of Croatia which included Syrmia within its borders, Dimitrije Bašićević ‘took refuge in Vienna together with his father and younger brother, where between 1942 and 1944 he studied art history and philosophy’.8 Austria, which had been annexed to the Third Reich in 1938, was a safer place for the Bašićević as ethnic Serbs than the Independent State of Croatia, where they fell under the Ustashas’ extended application of racial laws. In a text written by Bašićević’s brother Vojin, one finds information that in Šid, their father Ilija and his two sons had been ‘sentenced to death by a mobile martial court’, which means that they were hostages on a list that ‘basically meant a death sentence without a specific time of execution’.9 The list also included Sava Šumanović, a painter from the same town who was shot dead by the Ustashas in August 1942 and whose work would be the subject of Dimitrije Bašičević’s doctoral dissertation, defended in 1957 at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences in Zagreb. According to Mangelos’s brother, their own diligent and apolitical father was ‘first maltreated by the Ustashas and then almost destroyed by the Communists,’10 who declared him a kulak and took away his land.

Reviewing his Zagreb City Galleries employee file, Branka Stipančić noticed that Bašičević had omitted from his biography the fact that he had studied art history at the University of Vienna, where his professors included Hans Sedlmayr, Karl Oettinger, and Fritz Novotny. Stipančić believes that the reason for this was Bašičević’s presumption that, in post-war communist Yugoslavia, his stay in Vienna during World War II might be misunderstood.11 However, another question arises for me here: What was the effect of the lectures of Hans Sedlmayr, a despiser of modern art and a member of the National Socialist Party even before the Anschluss, on the student Bašičević, who had fled Syrmia before the local version of the final solution? At the Department of Art History at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences in Zagreb from which Bašičević graduated in 1949, per the general practice of academic art historians in Croatia and other republics of former Yugoslavia, Sedlmayr’s theories were not then – nor have they ever been – (re)considered in the context of his National Socialist convictions. Consequently, an even more important question arises: that of the relationship between Mangelos’s noart and Sedlmayr’s derogatory terms Unkunst and Nichtkunst.

Dimitrije Bašičević aka Mangelos was a polyglot, a passionate reader of philosophical and scholarly literature,12 an expert in avant-garde movements and currents within national and international modern art. When asked why he used different languages in his work, Mangelos answered in 1982 that he did not know.13 Hardly more informative is his ‘explanation of noart’ (1979), which reads: ‘the most philosophical / and most theoretical / explanation of noart / is / noart.’14 In 1980, at the request of Goran Petercol, Mangelos wrote an ‘introduction to noart’, first published in Quorum magazine (no. 1) in 1989, after his death. The text is structured into the following chapters, ‘triumph of instinct’, ‘triumph of war’, ‘triumph of doubt’, ‘self-confrontation’, and ‘September 18, 1980’, and starts like this:

there was a time when people were dying and there were no ideas. people were dying en masse, forcibly brought to an end. it was not literature. it was completely different. completely different from all literary dying. or natural. different from every picture, from every song, from every piece of news in the paper, and it didn’t look like history. not at all. not even like the familiar life. it was the time of death. in dying, books smelled of death, and reading smelled of dying. the books did not agree with what was left of breathing, so that the rustling of their paper lies could be heard in the silence of the steps of truth that were disappearing in death.15

When Mladen Stilinović asked him when and how the artworks titled paysage de la mort were created, Mangelos answered that in 1941, when a close relative was killed among many people from his surroundings, including colleagues, friends, and acquaintances, he was deeply shaken and, in a way, prompted to mark that death.

I made the mark so that in one of my notebooks, in which I wrote with black pencil or watercolour, or perhaps it was ink or ink wash, I made something like a stroke, as if he had been erased by that, or rather what was beneath him, although there was nothing beneath him, but that was my thought of that man who was now gone. He had been wiped out, and at the same time it was his grave, the sign of the grave. These were rectangular areas, at first very small and later they became large, so that they occupied a quarter, then a half, and sometimes the whole page, but the first ones were very small – they occupied one twentieth of the page. I recorded these deaths in 1941 and 1942, burying my childhood and youth in a way.16

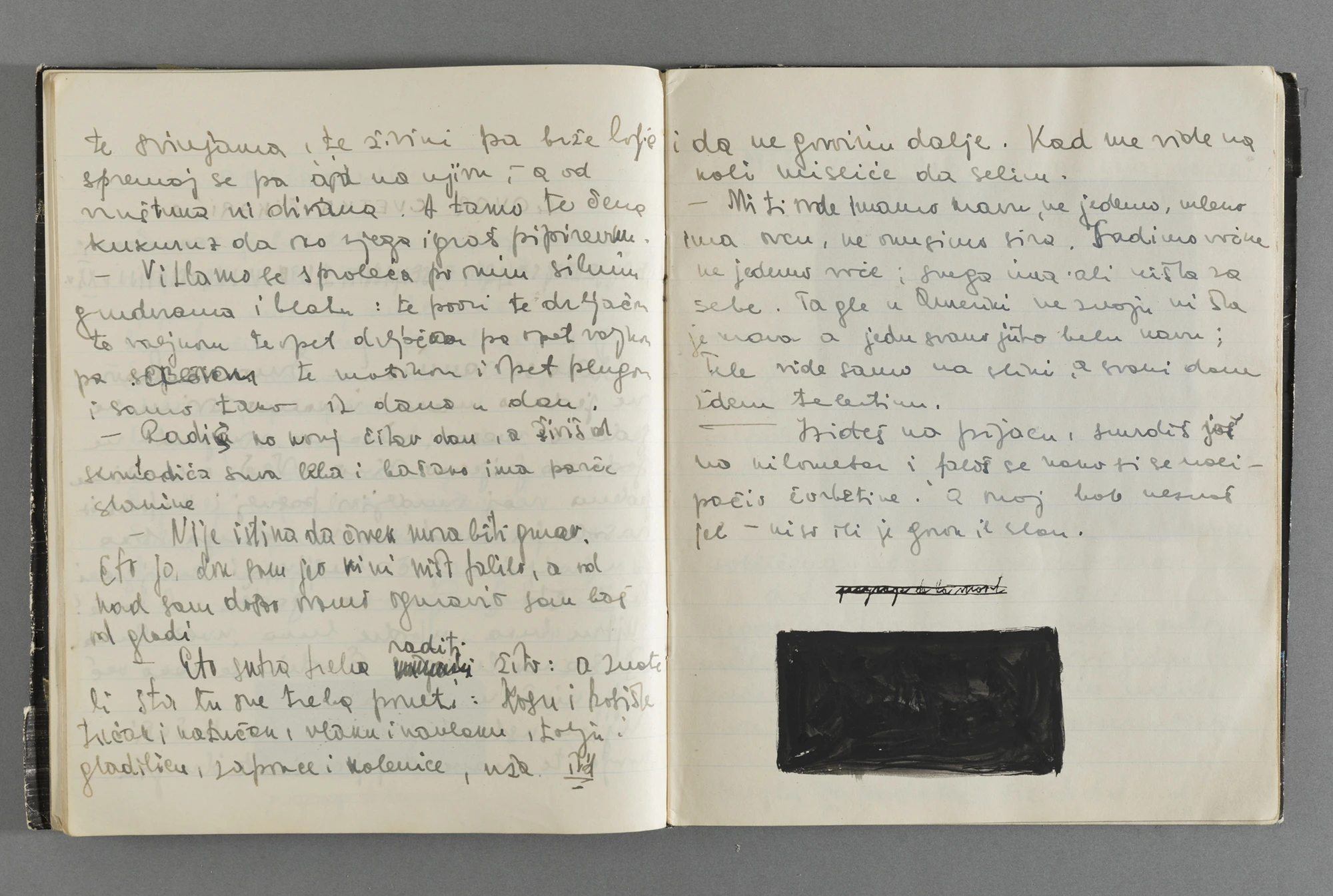

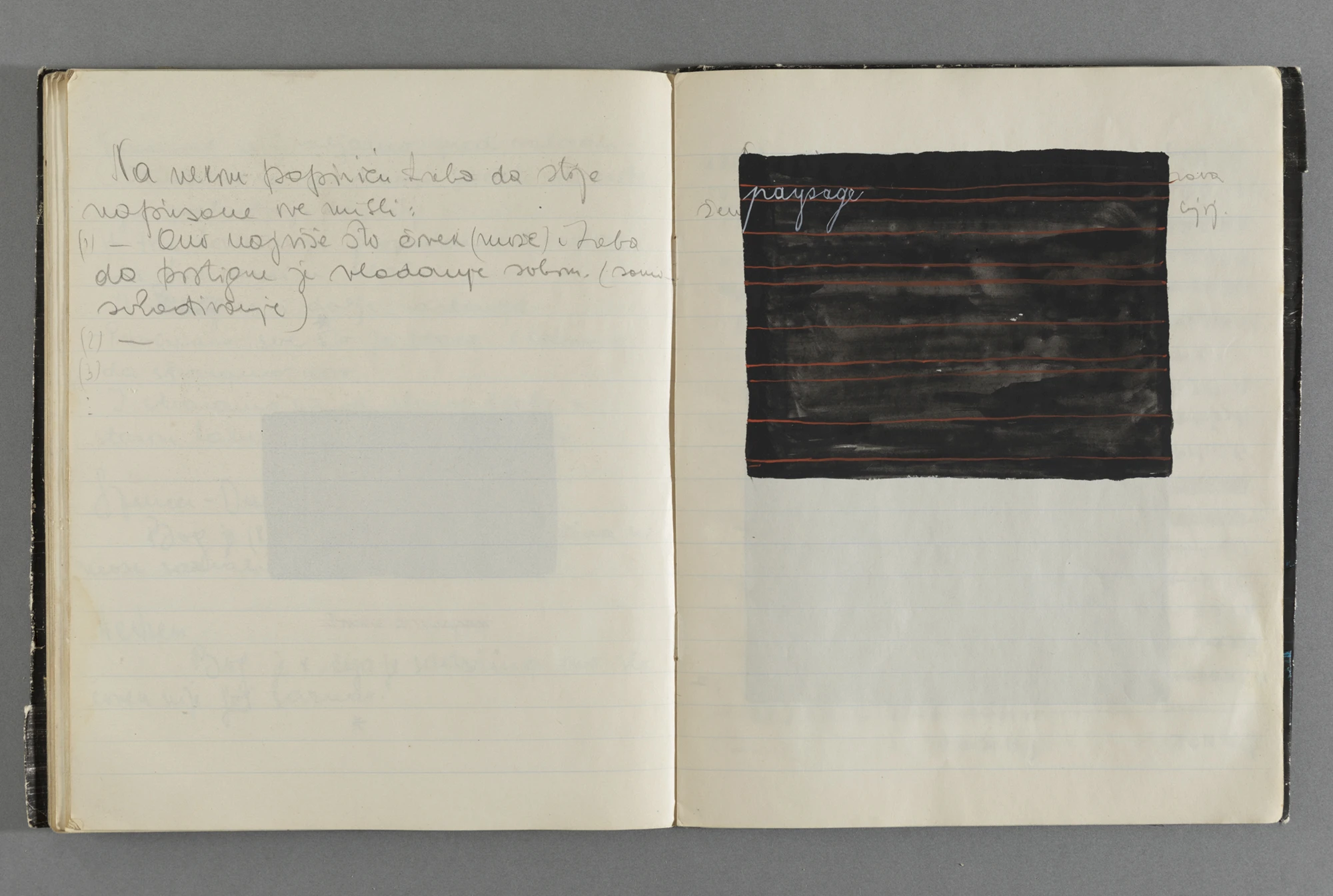

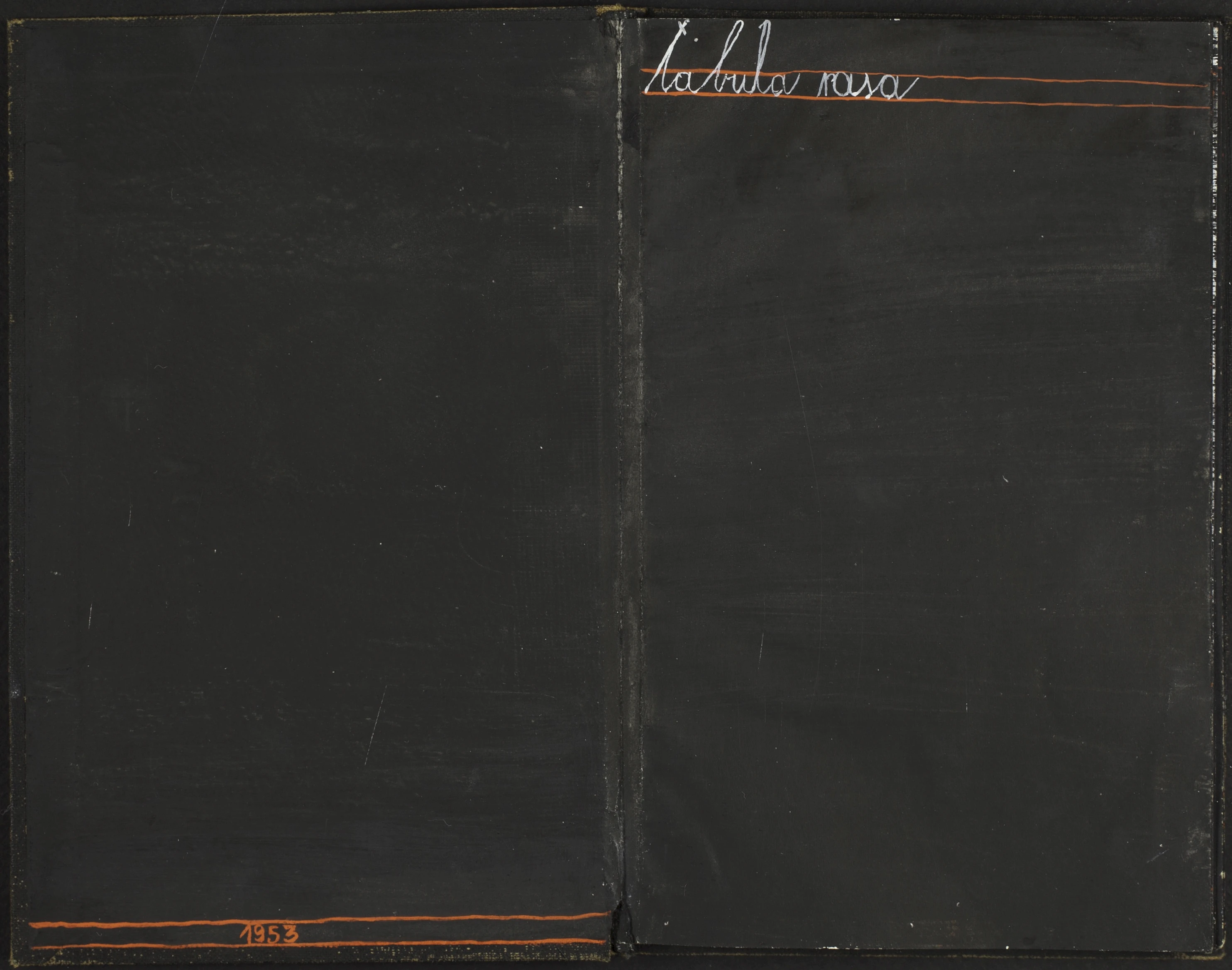

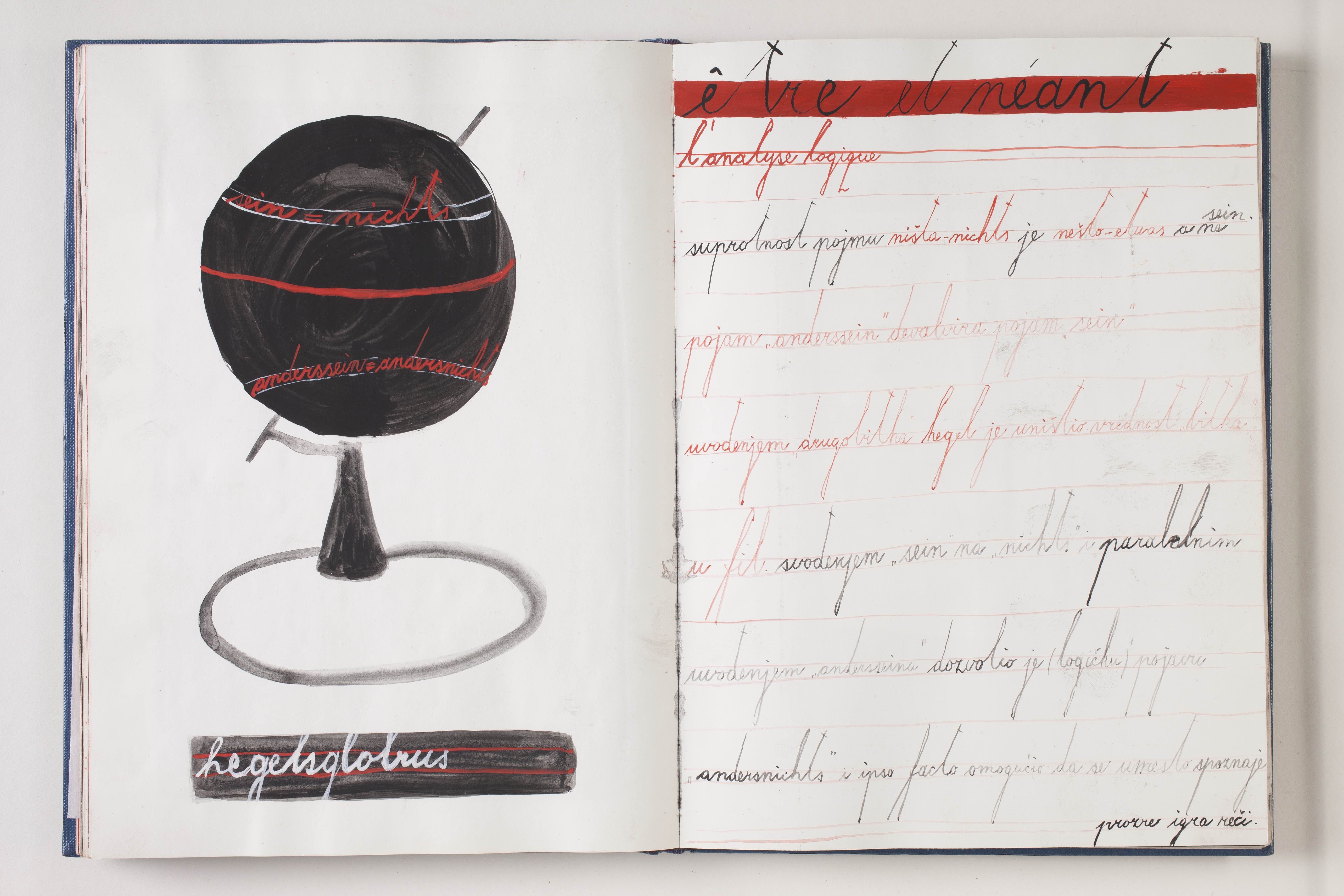

From the same interview one learns that he was hiding these notebooks by burying them in the barn, and that after Mangelos’s return from exile, the ‘graves’ marked in them became a tabula rasa. Tabula rasa, a term often conceptualized as denoting a ‘blank slate’, per the metaphorically expressed belief that there is no cognitive content in the mind before experience, literally denotes a scraped tablet, one from which the previous content has been erased, just like the people whose graves were marked in Mangelos’s paysage de la mort. In 1964, the sentence ‘I expect the resurrection of the dead’ would appear written in white and red on a black-painted wooden board, and around 1977 a black globe with words inscribed between red lines, such as the ones appearing on school blackboards, would become la manifeste sur la mort. In another work, it was the word ‘memoria’ that found its place between the red lines on black-painted plywood.

Memory is a term that refers to a trace of what existed before the tabula became rasa. In Mangelos’s case, what is remembered escapes verbalization and visualization, so it cannot become a tableau. That is why it was necessary to annul the picture, to perform what he termed the ‘négation de la peinture’. Mangelos produced the works called tabula rasa at the same time as those in which he negated painting, and they were preceded by the paysage de la guerre: ink-covered, inverted geographical maps (including one depicting the territories of Croatia and Serbia around 1070) probably made between 1942 and 1944,17 while Dimitrije Bašičević was studying art history in Vienna. And philosophy.

Inspired by a Vienna Globe Museum exhibit – a completely black globe that once served as a teaching aid and could be written upon with chalk – Branka Stipančić has suggested that during his stay in Vienna, ‘Mangelos, then still latent within the young student Bašičević, might have come upon this globe that, as we were to find out many years later, was for him the perfect ground on which to write out the pithy thoughts and manifesto’.18 Or, I would say, on which to reply to Professor Sedlmayr’s interpretive models by inventing his own noart, which erased the boundary separating art from discourse on art. In the 1970s, Mangelos was no longer latent in the curator and theorist Bašičević, so it is not surprising that the artist’s manifestos, such as the one on photography, presented theses that were consonant with those elaborated by the theorist Bašičević in his text ‘Consequences of Photography: 11th Digression on Culture and Art in the 1970s’.19

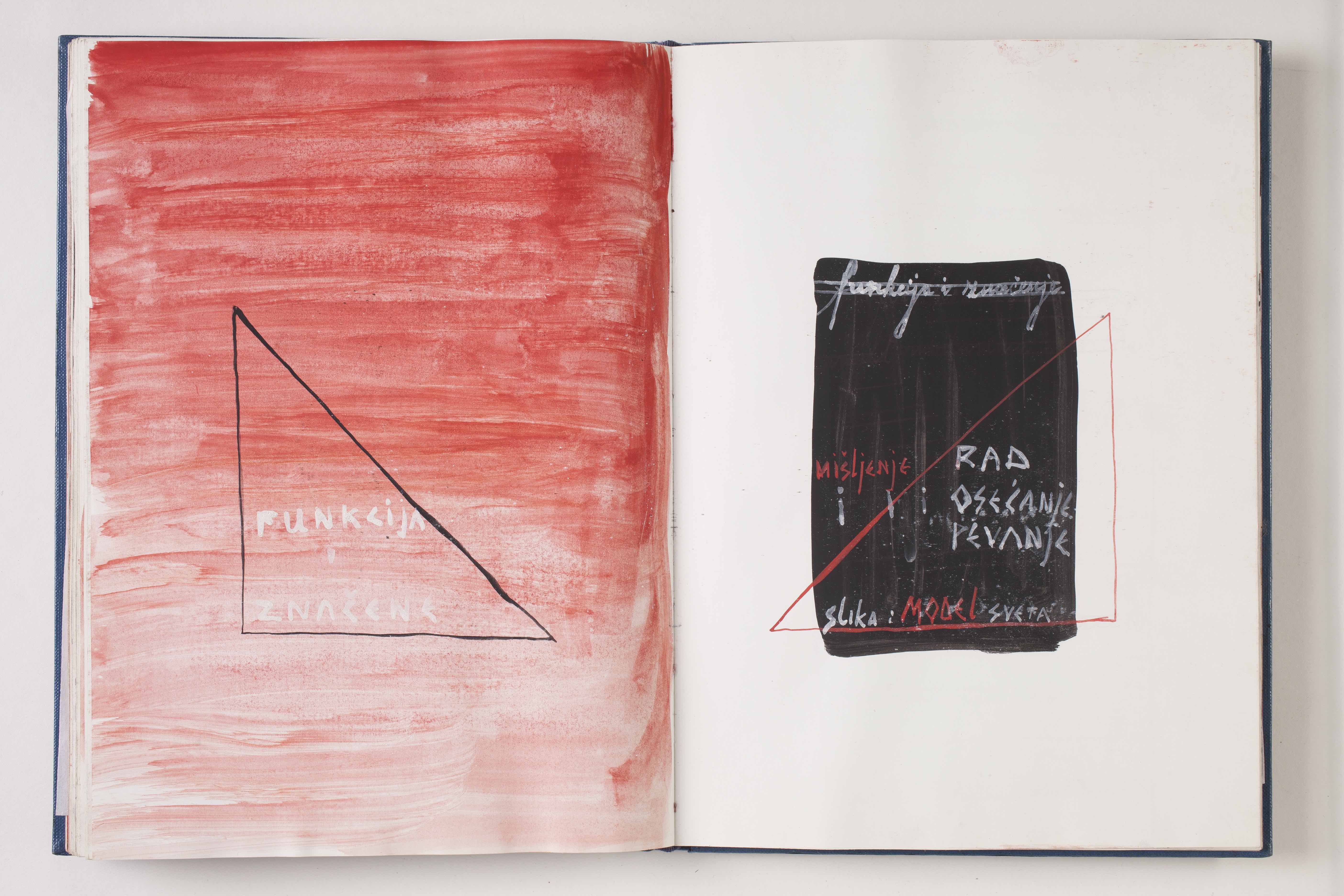

In the ‘Consequences of Photography’, Bašičević wrote ten digressions. The echoing absence of the eleventh digression announced in the essay’s title was amplified in thought, connoted by the empty space of the sentence that had been withheld. I am convinced that the title refers to Karl Marx’s eleventh thesis on Ludwig Feuerbach, which reads: ‘The philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point, however, is to change it’, to which Bašičević responded with silence while he wrote about the changed world. Like Walter Benjamin, whom he undoubtedly read, he rejected historicism and speaks from the position of historical materialism, as he understood that in a world constantly changed by technological revolutions, the conceptual boundaries of art per se could not remain intact. That is why Mangelos in his manifestos, and Dimitrije Bašičević in his theoretical texts, persistently emphasized the difference between metaphorical (or naive) and functional thinking:

Replacing the manual mode of labour with machines is most closely related to replacing the old, metaphorical way of thinking with [the] instrumental, which was, on the one hand, a cultural revolution correspondent to the one by which work and thought had established the culture of our species, and on the other hand led to a division of the world into old and new, that is, into two civilizations; the civilization of manual labour and metaphorical thinking, and the civilization of mechanical labour and instrumental thinking.20

Among Mangelos’s manifestos, there is a globe dated between 1971 and 1977, entitled relations manifesto (m. 4 – m. 8).21 Its northern hemisphere is painted over in white and the southern in black acrylic; the northern has the black text ‘functional thinking’ written between the lines, the southern, the white text ‘paysage de la mort’. The title of this manifesto demands a reflection on the equator, that is, on the line where functional thinking touches the landscape of death. In Latin, the word ‘aequator’ means equalizer.

At this point, I inevitably recall the sentence with which Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno opened their Dialectic of Enlightenment, written during their American exile at the same time as the young Bašičević was studying in Vienna: ‘Enlightenment, understood in the widest sense as the advance of thought, has always aimed at liberating human beings from fear and installing them as masters. Yet the wholly enlightened earth is radiant with triumphant calamity.’22 The Dialectic of Enlightenment explains in detail the genesis and destructive effects of rationalism and rationalization, that is, of functional thinking whose ultimate consequences would be manifested in the industrial production of death, more specifically denoted by the word Auschwitz.23 At a time when the Fifth Mangelos (1951–56) was performing his négation de la peinture and produced the works he called tabula rasa,24 including the book les paysages de tabula rasa, Alain Resnais articulated his cinematic reflection on the Holocaust, the essay film Night and Fog, finished in 1955. By editing contemporary footage of desolate landscapes, railway tracks intersecting them, and the ruins of the architectural complexes of Auschwitz and Majdanek, cutting them together with archival footage produced by the Nazis themselves while documenting the technology of the final solution, Resnais raised questions about recognition. Do we see that the camp, like a modern city, has a precisely designed urban structure? Production facilities, apartment blocks, scientific research and hospital facilities, a brothel and a crematorium? Do we see that production there was rationalized, every substance was suitable for recycling, that nothing was left to chance and improvisation? As the film shows the landscape of death, the narrator’s voice asks: ‘Is it in vain that we try to remember?’

Dimitrije Bašičević Mangelos: Fragmenti, 1936-1942, artist book, courtesy of Mario Bruketa

The Ustasha version of the final solution is specifically rendered by the word Jasenovac, and unlike the Nazi original, it belongs not to the civilization of industrial, but rather to that of manual labour. No metaphor. But here, too, it should be asked whether our trying to remember is in vain. In analysing Resnais’s Night and Fog, Phillip Lopate has argued that it is an anti-documentary film because this particular reality cannot be ‘documented’ – we are defeated in front of it in advance because it is too heinous. Wondering what can be done about this, he concludes that Resnais and his screenwriter Jean Cayrol (himself a former camp detainee) gave the following answer: ‘We can reflect, ask questions, examine the record, and interrogate our own responses. In short, offer up an essay.’25

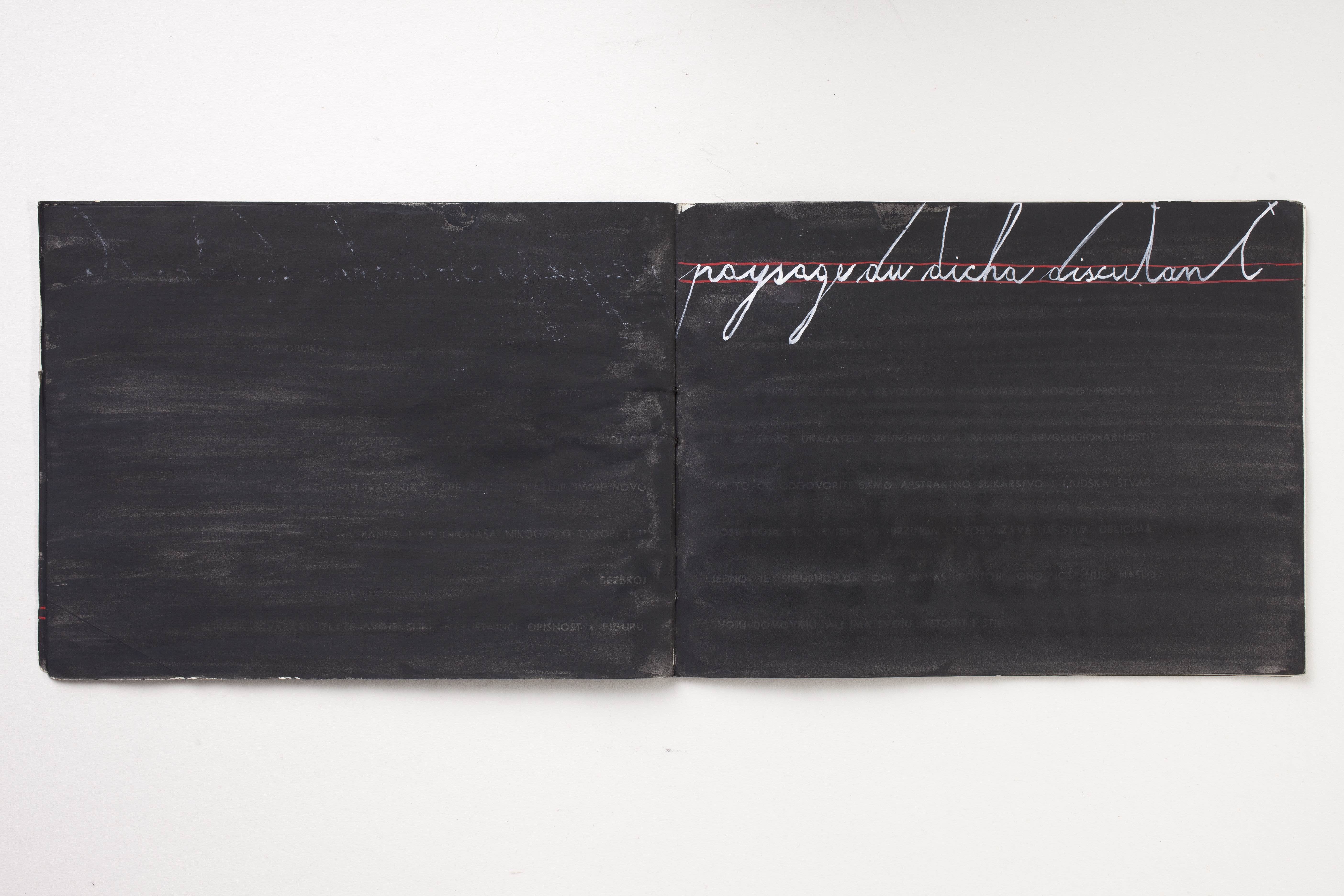

Mangelos offered anti-painting. And anti-poetry. Works he made between 1942 and 1944, entitled paysage de la mort, paysage de la guerre and paysage de la deuxième guerre mondiale – landscapes where a breakdown of sense occurs, including the meaning articulated by the newspaper or book text which, covered by a coating of black tempera, serves as a ground for a particular landscape – are undoubtedly anti-paintings. For ‘the books did not agree with what was left of breathing, so that the rustling of their paper lies could be heard in the silence of the steps of truth that were disappearing in death’, as he wrote in his ‘introduction to noart’.

Mangelos’s black leads me to Goya’s black. Was Mangelos’s horror at these ‘paper lies’, or the ultimate outcome of the ‘civilization of functional thinking’, analogous to that felt by Francisco Goya, the so-called ‘last of the Old Masters and first of the moderns’, when he realized that the Enlightenment ideals had ended in Napoleon’s conquests?26 In turn, the trajectory of Goya’s Capricho 43 – El sueño de la razón produce monstruos, Los desastres de la guerra, and Los disparates leads me to the Mangelos globe entitled relations manifesto (m. 4 – m. 8), whose equator equates functional thinking with the landscape of death.

Goya’s El sueño de la razón produce monstruos (1797–98), which has also been interpreted as a self-portrait, ‘looks like a philosophical conception of relations between imagination and reason’ that is analogous to Mangelos’s conception of relations between pre-modern and modern, metaphorical and functional ways of thinking – i.e. between the civilization defined by manual labour and that defined by the machine labour of industrial, rationalized production.27 When asked by Mladen Stilinović about the works in which he wrote letters from different scripts – Latin, Cyrillic, Glagolitic, Gothic, Greek, not even omitting runes – Mangelos answered:

I should say that this phase, apart from those letters, included another problem or motif, which was the motif of non-painting or antipeinture, the negation of painting. And they get into a whole complex of problems, and I am in a way fighting against paintings, I create paintings from letters. I wanted to fight the irrational part of that which the painting brought with it. Believing that I would negate it with the letter, which is an element of rational thinking.28

In Goya’s Capricho 43, the text ‘El sueño de la razón produce monstrous’, written on the side of the table at which a figure (the artist?) has fallen asleep, is likewise a manifestation of rational thinking that, in articulating the same problem to which Mangelos referred, comes to seem like a Mangelos manifesto.

Mangelos’s works, which, in accordance with changing artistic and theoretical paradigms, have been quite assuredly considered in the context of the notion of art since the 1970s, were not intended for an audience at the time of their making. Nor did Mangelos ever call himself an artist. In his words, ‘it was a strictly private matter, because I didn’t bother at all to show things, nor did I bother to exhibit, although I did exhibit now and then. For me, they are still private.’29 Goya’s Pinturas negras, which he painted on the interior walls of his house Quinta del Sordo on the outskirts of Madrid, were also his own private affair, not intended to be viewed by other people. They were created between 1820 and 1823, in the decade following Napoleon’s invasion of Spain. Napoleon’s ‘conceptualization of space’ foreshadowed the twentieth century, in which, beyond all metaphor, the landscape of death would emerge as the cultural dominant. Goya’s ‘negation of painting’, more precisely his establishment of the category of counter-painting, at the dawn of the modern, industrial age of rationalization, was as radical as Mangelos’s négation de la peinture or antipeinture would be in the following century.

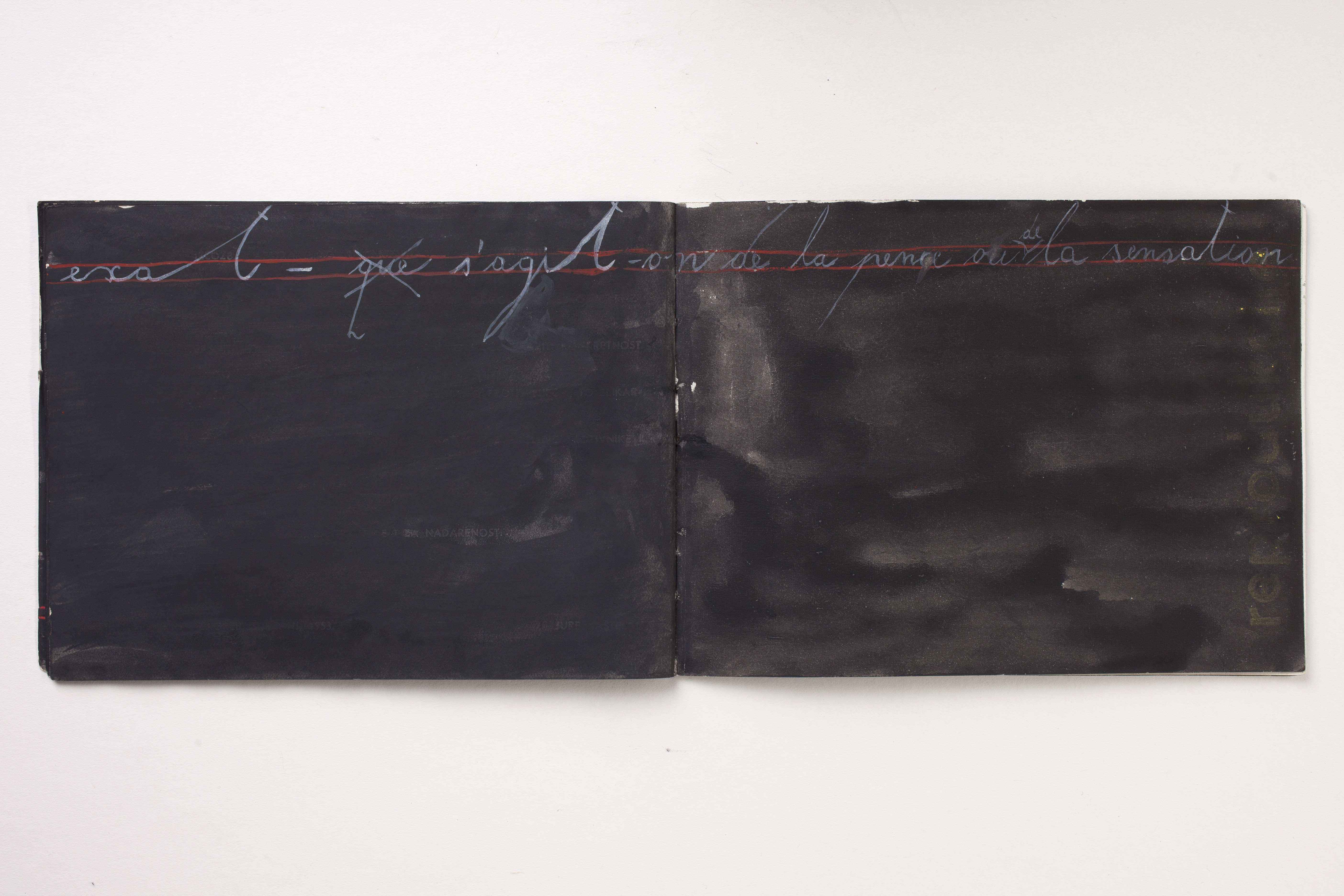

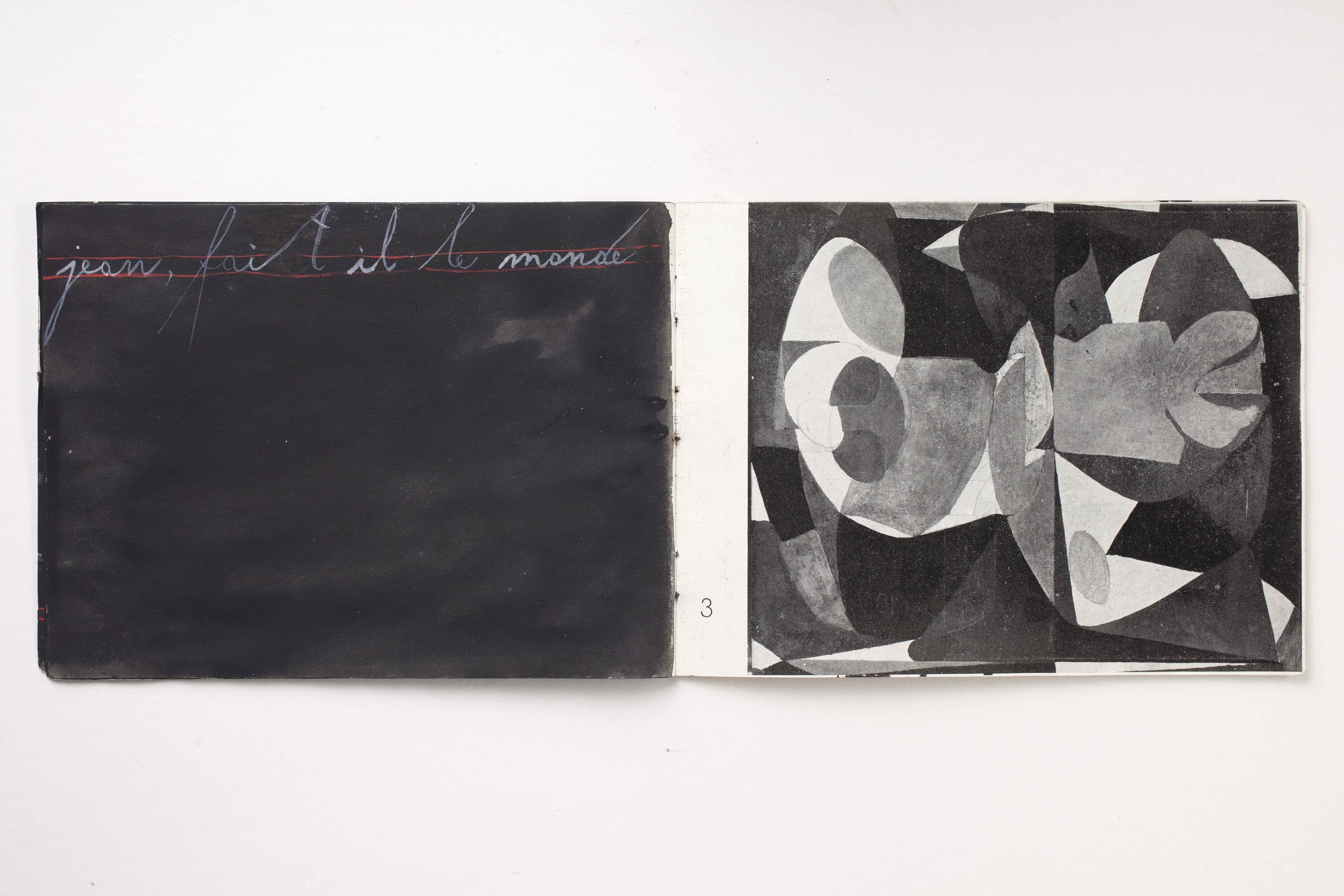

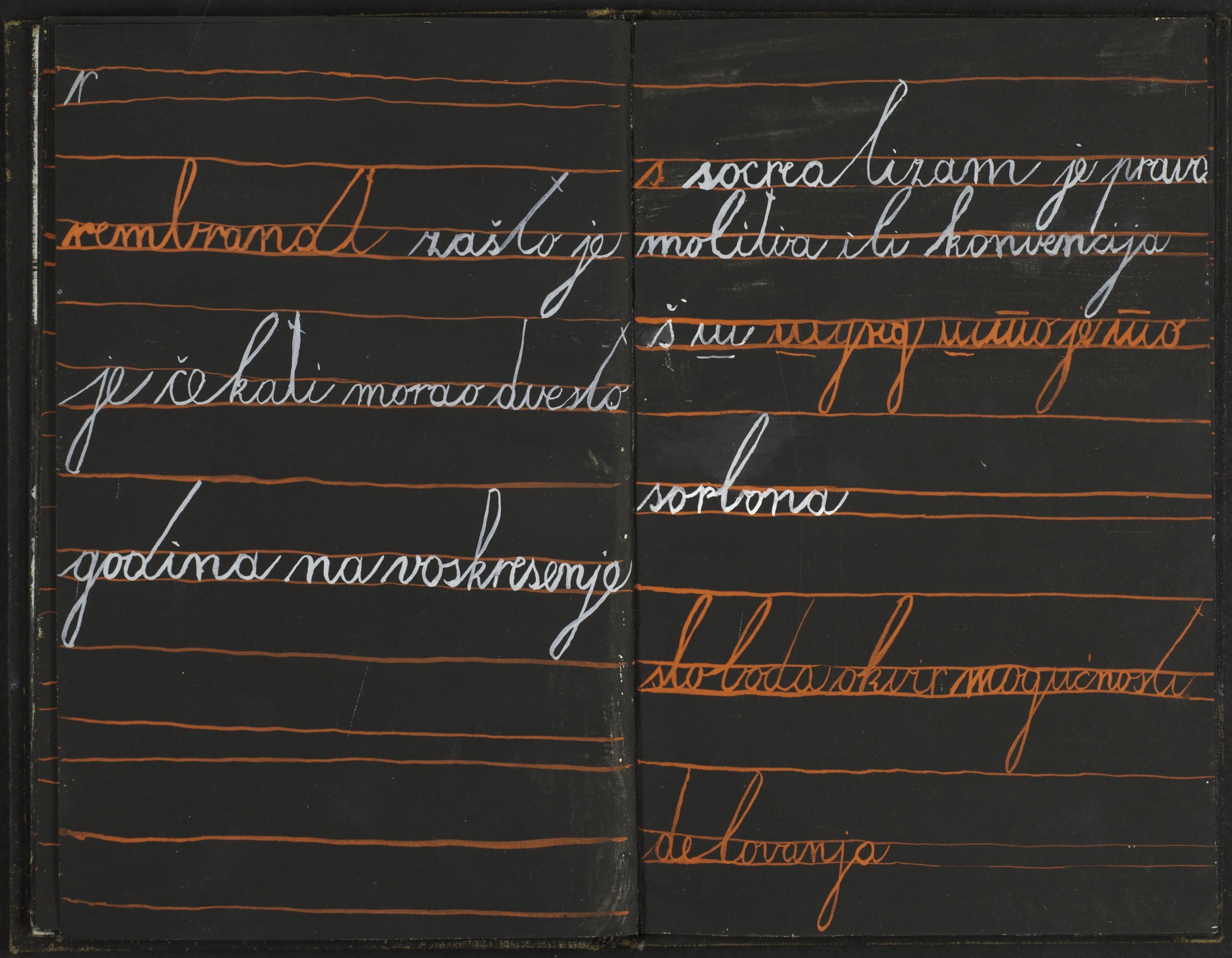

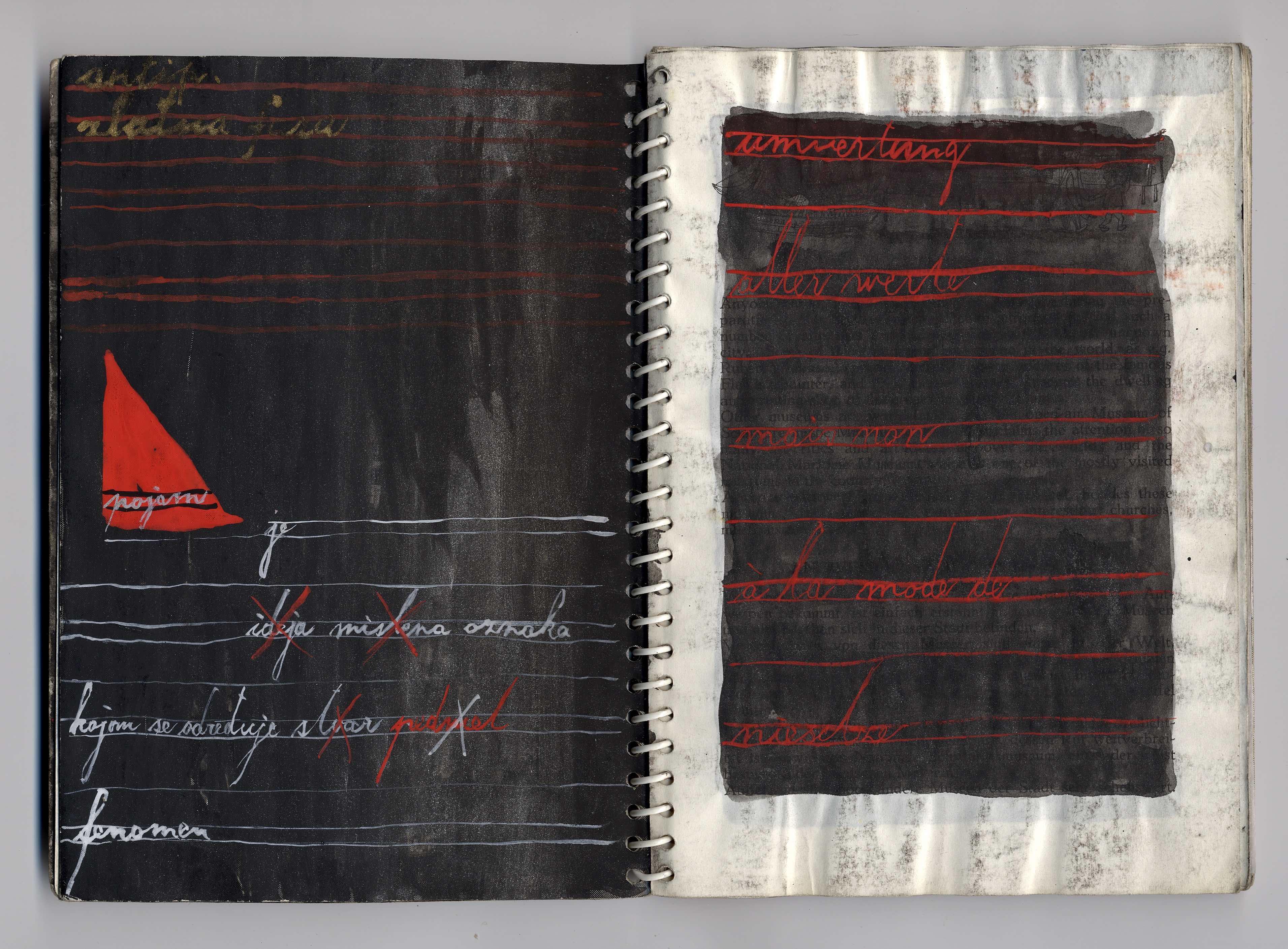

Dimitrije Bašičević Mangelos: Les paysages de tabula rasa, 1953, artist book, courtesy of Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb

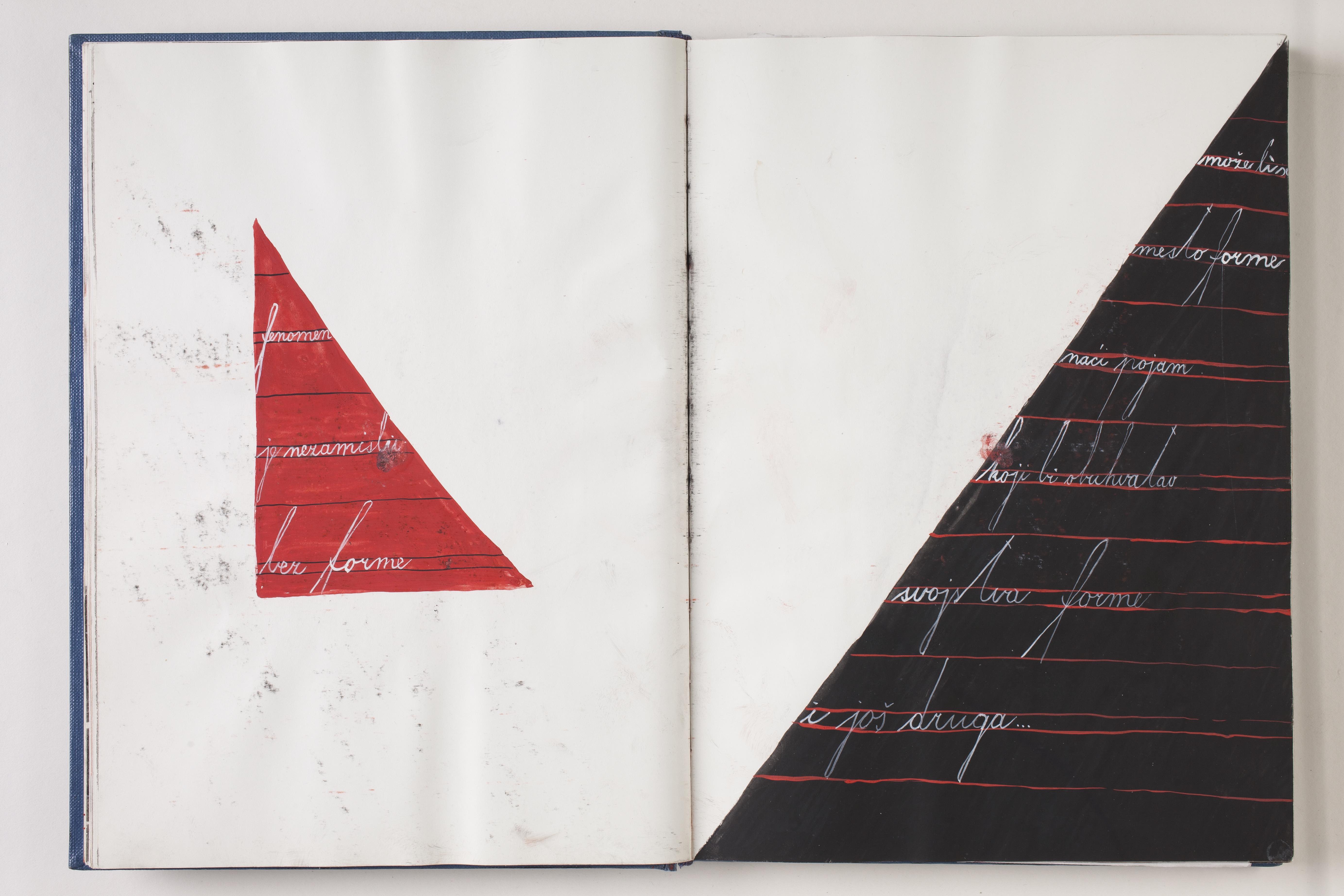

One of the very few books that Mangelos did not turn upside down while negating painting, and moreover that he left the text of legible, only blackening and crossing out in red the reproductions published in it, was the catalogue of a Sava Šumanović exhibition held at the New University in Belgrade in 1939, three years before the painter from Šid was taken hostage, brought to Sremska Mitrovica and shot. In the blackened reproductions, the Fifth Mangelos (1951–56) drew a set of red lines similar to those appearing on school tablets, and over them a sign resembling Saint Andrew’s cross, or the letter (or Roman numeral) X. On one of the pages of les paysages de tabula rasa (1953), a book from the same period, the same set of lines appears with the statement: ‘tabula rasa no. 1 is my school tablet’. That same year, Narodni list published ‘In the tradition of Josip Račić’, an essay by art historian and critic Dimitrije Bašičević in which he articulated in words the meaning of the sign that appeared in Šumanović’s catalogue (as a ground for anti-painting) as an act of negating painting.30 He wrote:

Carrying in yourself abysses of obscure depths and a longing for unattainable heights, for which biblical allegory invented the symbol of crossed lines [my italics], a stubborn, innate and acquired faith in life and oneself, and a bleeding doubt – these two opposites, which ignite and suffocate each other, between which the figure of a man and artist rises, all this is an epic with the attributes of tragedy. We also have that little bit of information about the tragedy; is not that bitter cup of life, spilled over the edge, the truest page of our art? Didn’t it ultimately allow for further steps? Aren’t his canvases a true and profound experience of life in art for the viewer? And so many hidden unrests behind the greyness of these surfaces!31

So many hidden unrests behind Mangelos’s blackness! How many ‘crossed lines’ that signify at the same time ‘a stubborn, innate and acquired faith in life and oneself, and a bleeding doubt’ are expressed by the statement written on the globe called la manifeste sur la mort, ‘il n’y pas de mort il s’agit d’une autre forme de la vie’ (‘there is no death, just another form of life’)? A different form of life is also indicated by Bašičević’s abovementioned text that begins as follows:

Our concepts are regularly static in nature; their dynamism comes forth only in traffic, not in a mutual relationship but on the way to the source, i.e. from the place where they emerge to the place where they will be accepted. On these bridges, the created concept meets its own variation; from these encounters, new variants (nuances) emerge.32

Mangelos’s concept of anti-painting emerged from, among other things, his encounter with Račić’s painting. For this reason, he made Račić an anti-homage by blackening a reproduction of one of his paintings on a page torn from a book, leaving visible only the painter’s printed name, which he further emphasized by marking it with two ‘crossed lines’ in red. In an essay outlining the transversals of the Račić tradition, Bašičević comes to Šumanović via the life and work of Milan Steiner:

Reality is not all on one level and a work of art contains projections of all levels of reality. … Contemporanéité. Meier-Graefe has referred to it as the ‘zeitgenösische Elemente’. Elements of the time, i.e. the reality, but always the ‘given’ reality. What is Milan Steiner’s ‘contemporanéité’? – The core is certainly the time between 1914 and 1918. These numbers are symbols of countless facts that have the property of repetition: cannons, queues for meat, meat for the cannons, deprived childhoods, fears. This content is repeated even when the voices differ. … The whole answer is the answer to the question about the mediators of these conditions. So we come back to biography. Let us recall that Steiner’s friend Šumanović, some ten years later, also fought against darkness with light from his fingers, with lyricism against drama.33

Mangelos did the same within his own given reality, aware of the fact that, as both Jacques Lacan and Michel Foucault would articulate in the 1960s, there is no pre-discursive reality. And that is why discourse, pictorial and verbal, became the subject of Mangelos’s interest. Discourse, what shaped it and what undermined it – in short, the relationship between words and things, probably also why he called some of his works paysage de mots. In French, the difference between ‘words’ (mots) and ‘death’ (mort) is a single letter – s or r. Mangelos focused on the performativity of words and letters, moreover on the irreducible difference between sounds and letters serving to transcribe sounds – the representations of sounds, so to say. As on the difference between the living body and the dead picture, because voice is an effect of bodily events that is inseparable from breathing, from life, while the written, immobilized letter can become a mortifying image. By being the fundamental social contract, a particle of language becomes law.

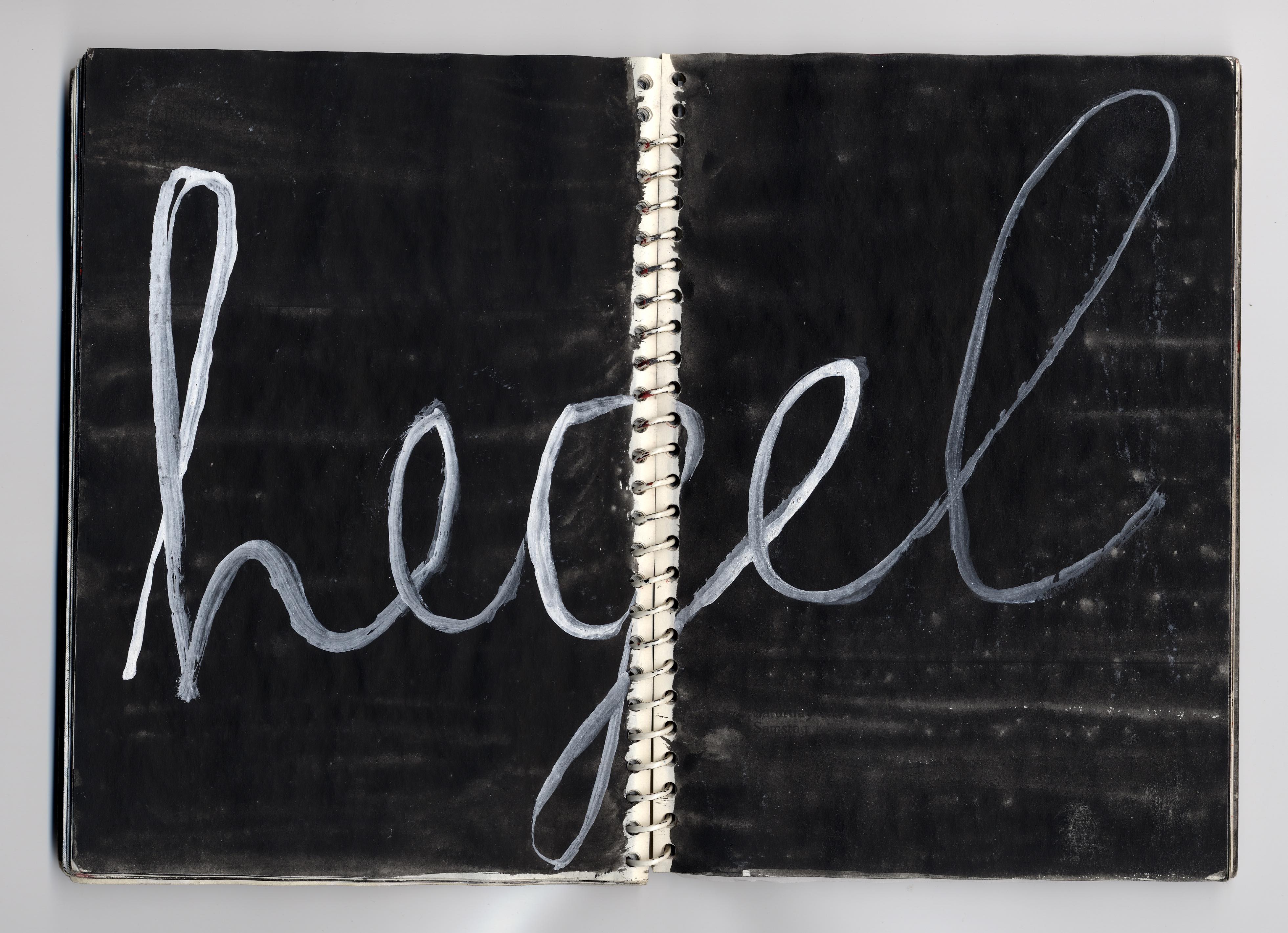

Dimitrije Bašičević Mangelos: Antiskice, artist book, 1963, courtesy of Museum of Contemporary Art Zagreb

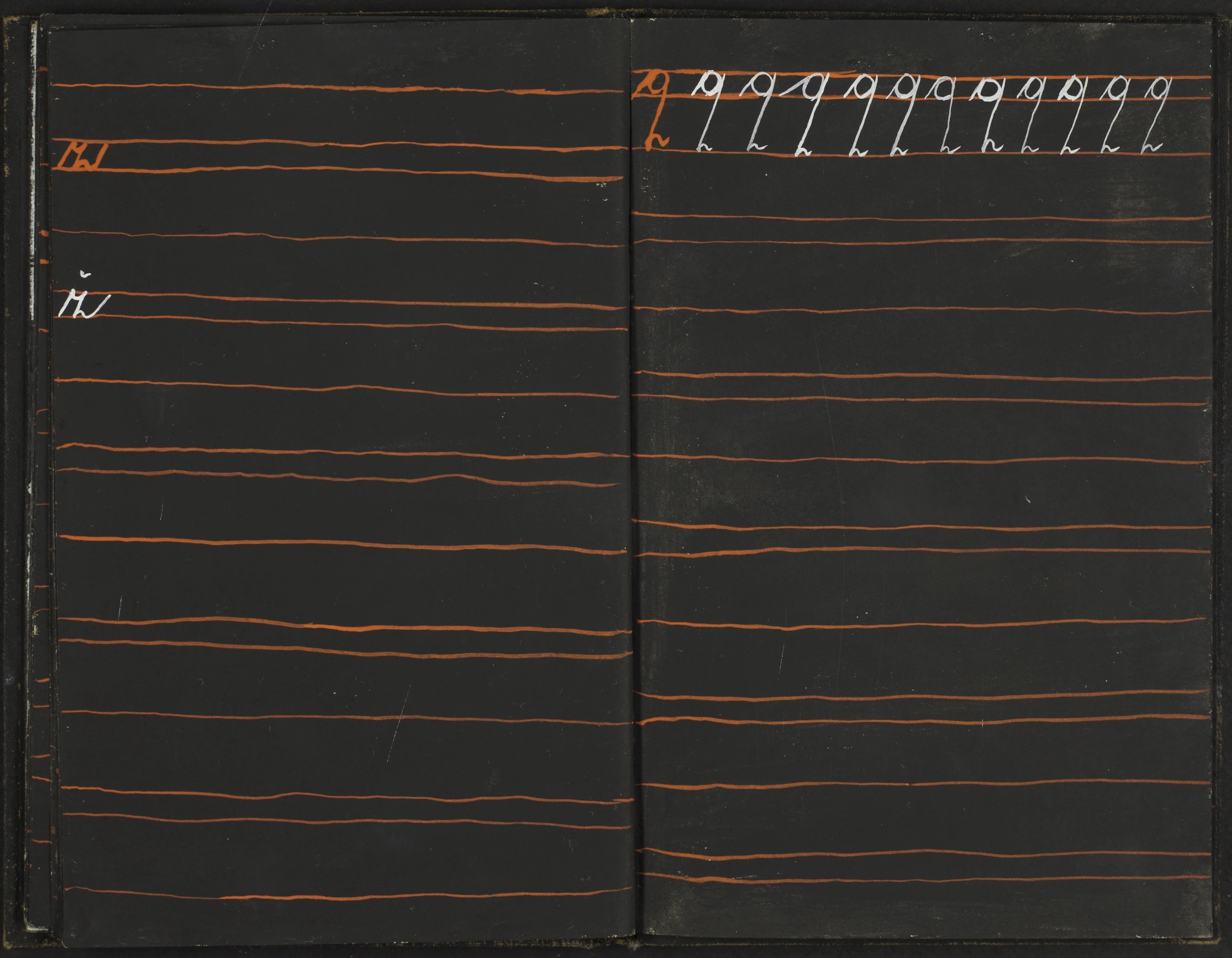

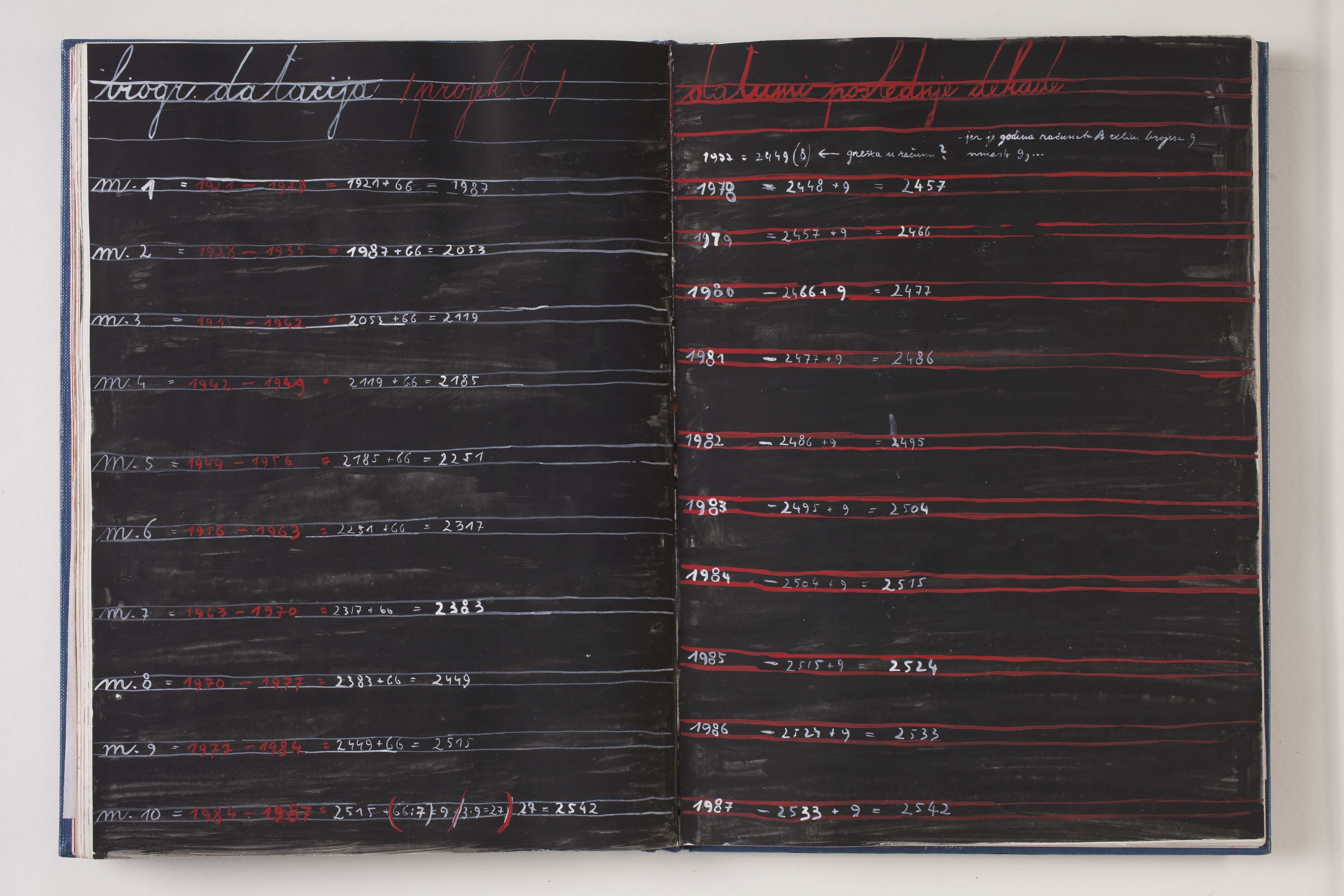

This is why Mangelos stated in his hammurabi manifesto that ‘there is no data to confirm / the conclusion on the development of thought / between hammurabi’s code and the hegelian logic / leaving us with the conclusion / that the system of thought / was completed / before hammurabi’. The manifesto is dated ‘a.d. 2449 in anda u tonia’. Both Hammurabi and the Roman settlement of Andautonia, whose ruins are located near Zagreb, as well as the year 2449 from which Mangelos announced his conclusion, point to the concept of non-chronological time that the totality of his work articulates. In 1896, Henry Bergson published his book on Matter and Memory: An Essay on the Relationship of Body and Spirit, which in the 1980s would become one of the pillars of Gilles Deleuze’s conception of non-chronological time, in his notions of time-image and crystal-image. In Bašićević’s critical texts Bergson is mentioned in passing, and Mangelos wrote the following formula on a double page of his anti-sketches (c. 1963): ‘the relationship of matter + memory + energy = the solution to the problem of the spirit’. The word ‘memory’ takes up another double page of his anti-sketches: on the left, he wrote it in black on a red-painted background, and on the right, the same word appears written in white six times on a black surface with a set of red lines. In the same notebook, he specified matter, energy and memory as super-categories, while in his manifesto on thinking no. 1 (c. 1977–78), he wrote: ‘thinking is a “form” of energy’. The idea of non-chronological time also permeates Rainer Maria Rilke’s only novel, published in 1910, at the dawn of World War I:

The passage of time had absolutely no significance for him, death was a minor incident that he disregarded entirely, people he had once absorbed into his memory continued to exist and their death meant not the slightest difference. Several years later, after the old man’s own death, people talked of how he showed the same obstinacy with experiencing the future as the present.34

In the same novel, Rilke wrote the imperative ‘Take another name, any name … and hide it from everyone’,35 as well as the sentence: ‘Now I see it that way, but I used to be most interested in reading as they wanted it.’36 It is impossible to assume that the anti-poet Mangelos had not read the poet Rilke. And it is indisputable that Dimitrije Bašičević took a new name under which he could stop reading in the way that an art historian was required to do.

Dimitrije Bašičević Mangelos: Jahnrensbuch, around 1970, artist book, courtesy of Mario Bruketa

I would say that Mangelos reads aloud. Gives voice to, more precisely. Mladen Dolar claims that the voice is that which does not contribute to making sense. It is the material element, recalcitrant to meaning, and if we speak in order to say something, then the voice is precisely that which cannot be said. It eludes any pinning down as the nonlinguistic, extra-linguistic element that enables speech phenomena, but cannot itself be discerned by linguistics.37 Faced with the voice, he writes, words structurally fail,38 because voice is a radical alterity of logos.39

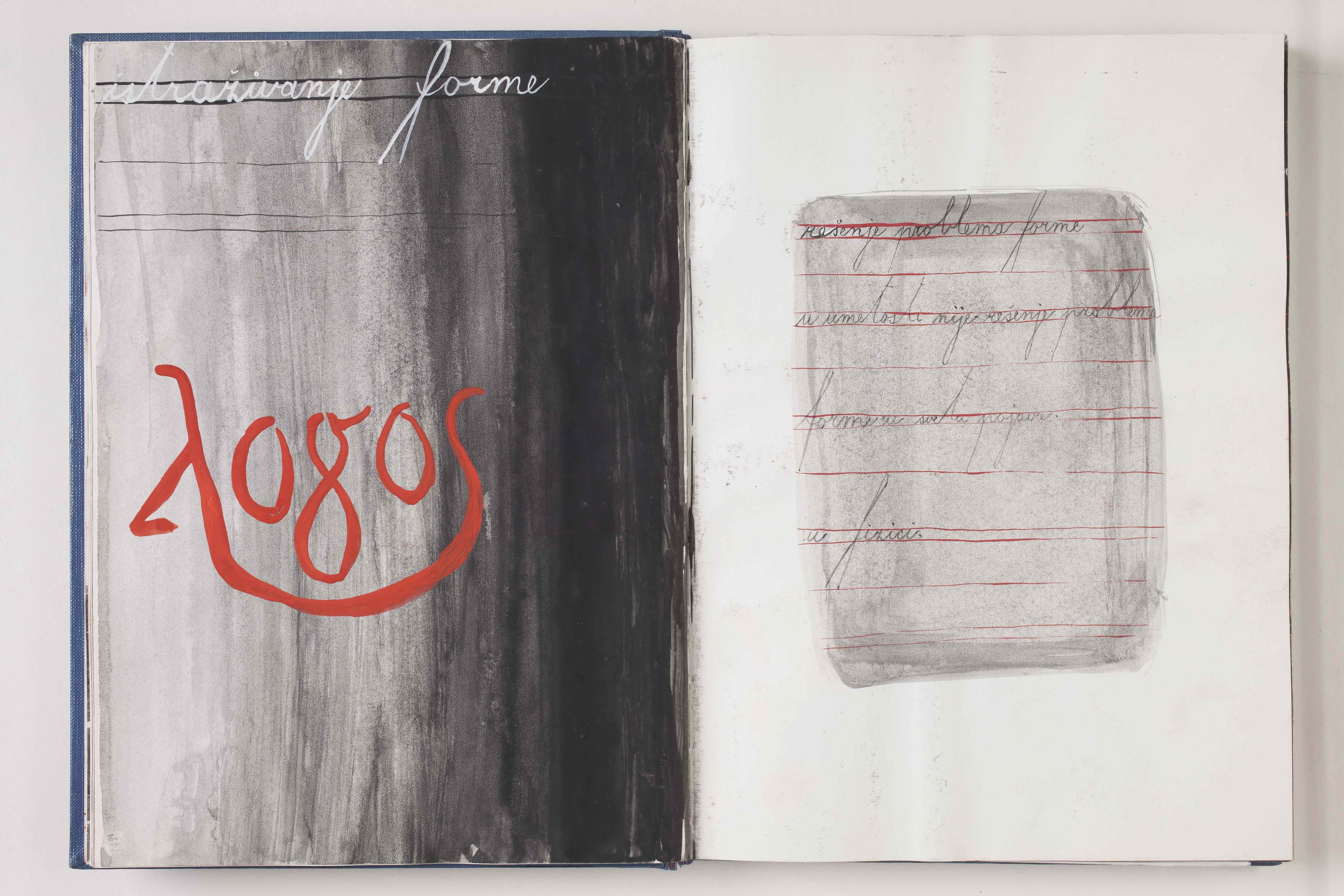

The referential field of Mangelos’s works is saturated with a wide range of meanings of the term logos and a multitude of manifestations of its signifiers. In his jahrensbuch (c. 1970), the left side, at the top of which he wrote ‘a study of form’ in Latin script, is dominated by the word logos written in Greek script, in which the same curve shapes the first and the last letter. On the opposite page, Mangelos wrote: ‘The solution to the problem of form / in art is not the solution to the problem / of form in the world of phenomena. / in physics.’ On a gold-painted board, the Seventh Mangelos (1963–70) wrote in red letters: ‘am beginn war es kein wort’ (c. 1963–70) (‘in the beginning was not a word’). This statement is radically opposed to the sentence that opens the Gospel of John (‘In the beginning was the Word’), which Mangelos transliterated from Old Slavonic in his anti-sketches (c. 1963) as ‘prežde je ubo slovo’, categorizing it as a nostory. Prior to that, the Sixth Mangelos (1956–63) had written ‘non credo’ in red letters on black-painted cardboard. The book titled script was made in 1949 by drawing signs resembling pictograms and ideograms on pages of the Holy Scripture painted-over in black, red or white, and by writing and redesigning letters from various scripts of related and unrelated languages. In the process of producing these signs deprived of their signifying function, he discreetly introduced the form of the right-angled triangle which, in script too, connotes Mangelos’s ostinato theme: Pythagoras.40

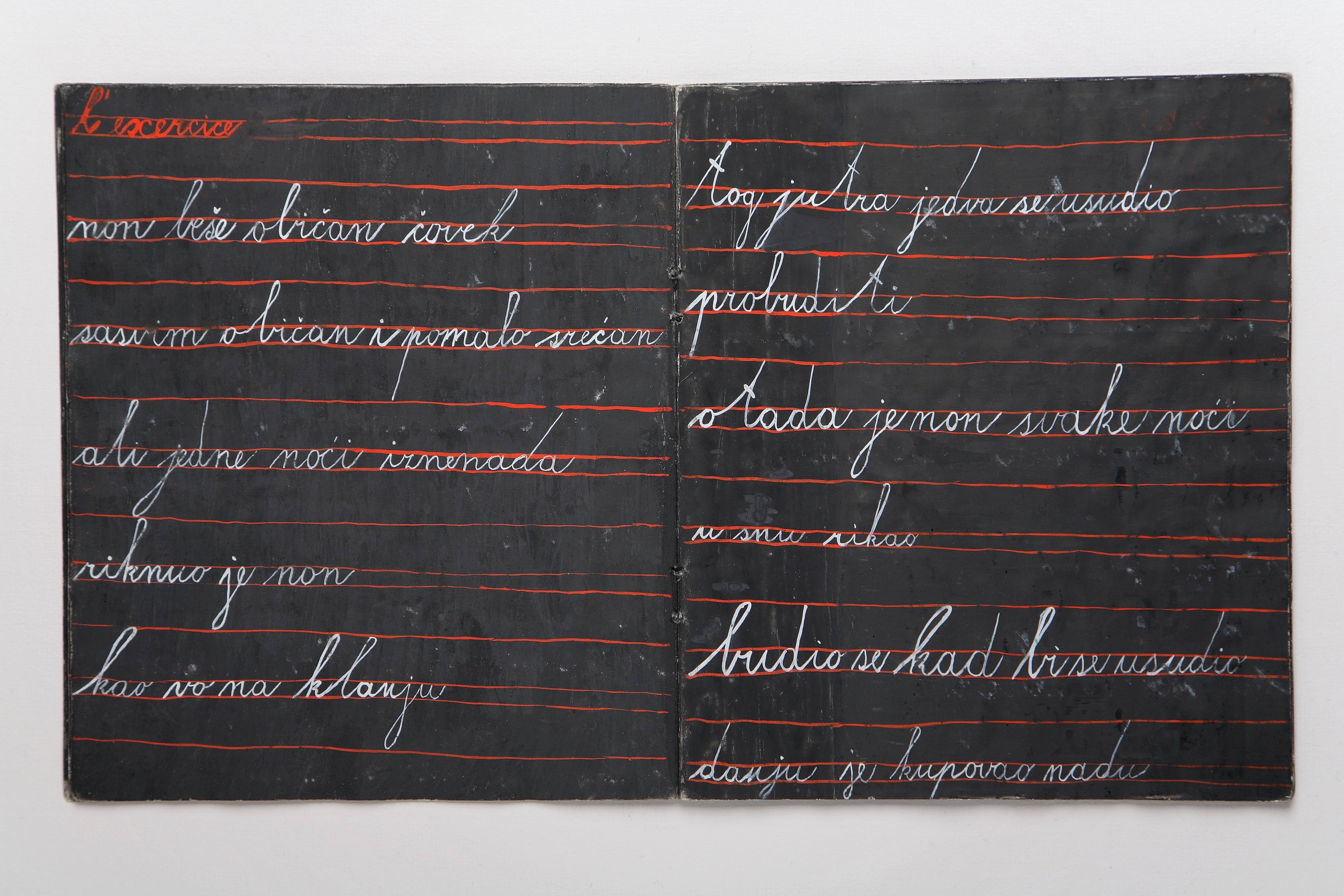

There is a book that Mangelos called pythagoras 2.41 In many other works, he wrote Pythagoras’s name and drew right-angled triangles within which he occasionally wrote different words. For example, the word ‘pythagoras’ appears on several pages of his book les exercises (1961), written in different scripts. On one of them, he added in a set of lines an ‘explanation of pythagoras’, which reads: ‘for the shortest / clear / and rational / formulation’. In the same book, the text ‘logos = praxis’ is written across a double page. However, Pythagoras’s teachings were far from mere rationalism, so Mangelos’s ‘Pythagorean credo’ is based not only on the functionality of a short and clear formulation of the basic trigonometric theorem, but above all on the imperative of a kind of thinking that is, according to Aby Warburg, not subject to border police restrictions.

Before founding a school in Croton around 530 BC, Pythagoras lived in a cave on Samos with twelve disciples. This biographical detail is encrypted in one of Mangelos’s nostories titled le konj qui chante: ‘it was quite late. they finally / came across the entrance and found themselves in / a magnificent cave where they / eagerly awaited a cure for their / anxiety. then that horse came / and said la marquise est sortie à cinque heures’.42 As in many other works, Mangelos here bastardized language not only to subvert its function of ‘the law’ with his typical wit,43 but also to emphasize the activity of spatial and temporal transversals in the thinking process which, for him, is a form of energy. That is why Marcel Proust’s Marquise wanders in here, not only as an expression of resistance to Paul Valéry’s understanding of modern literature,44 but above all as a trace of the material presence of (un)lost, non-chronological time. Because matter + memory + energy = a solution to the problem of the mind. According to some opinions, Pythagoras introduced the Egyptian teachings on metempsychosis, transmigration of the soul, into Hellenic thought. Is that what Mangelos’s statement ‘I expect the resurrection of the dead’ refers to? Or the dialogue mit dem tode, an oil on canvas from the stage of the Eighth Mangelos? Or the words animal and anima written one below the other in a black square on a red-painted page of his gottschalksbuch (1961–63)?

Mathematics, astronomy and music were studied at Pythagoras’s school, and it is believed that he was the first to connect numerical relations with sounds, establishing mathematical theory as the foundation of Western music. Harmony. In Mangelos’s works, the names of Bach, Beethoven and Hildegard von Bingen are among those that appear. Pythagoras’s students, who, separated from the teacher by a curtain, listened to his teachings for five years without being able to see him, were called acousmatics. The French composer, engineer and musicologist Pierre Schaeffer coined the term acousmatic sound, which the filmologist Michel Chion defined as sound that, unlike what Chion called visualized sound, lacked a clear source in an image. Seemingly omnipresent, omnipotent and omniscient, such sound evokes anxiety. Mladen Dolar has introduced the notion of acousmatic voice, defining it as a voice whose source cannot be seen and whose origin cannot be determined, a voice that cannot be situated anywhere. For Dolar, such a voice would be in search of its origin, a body which would not stick to it even if it found it.45

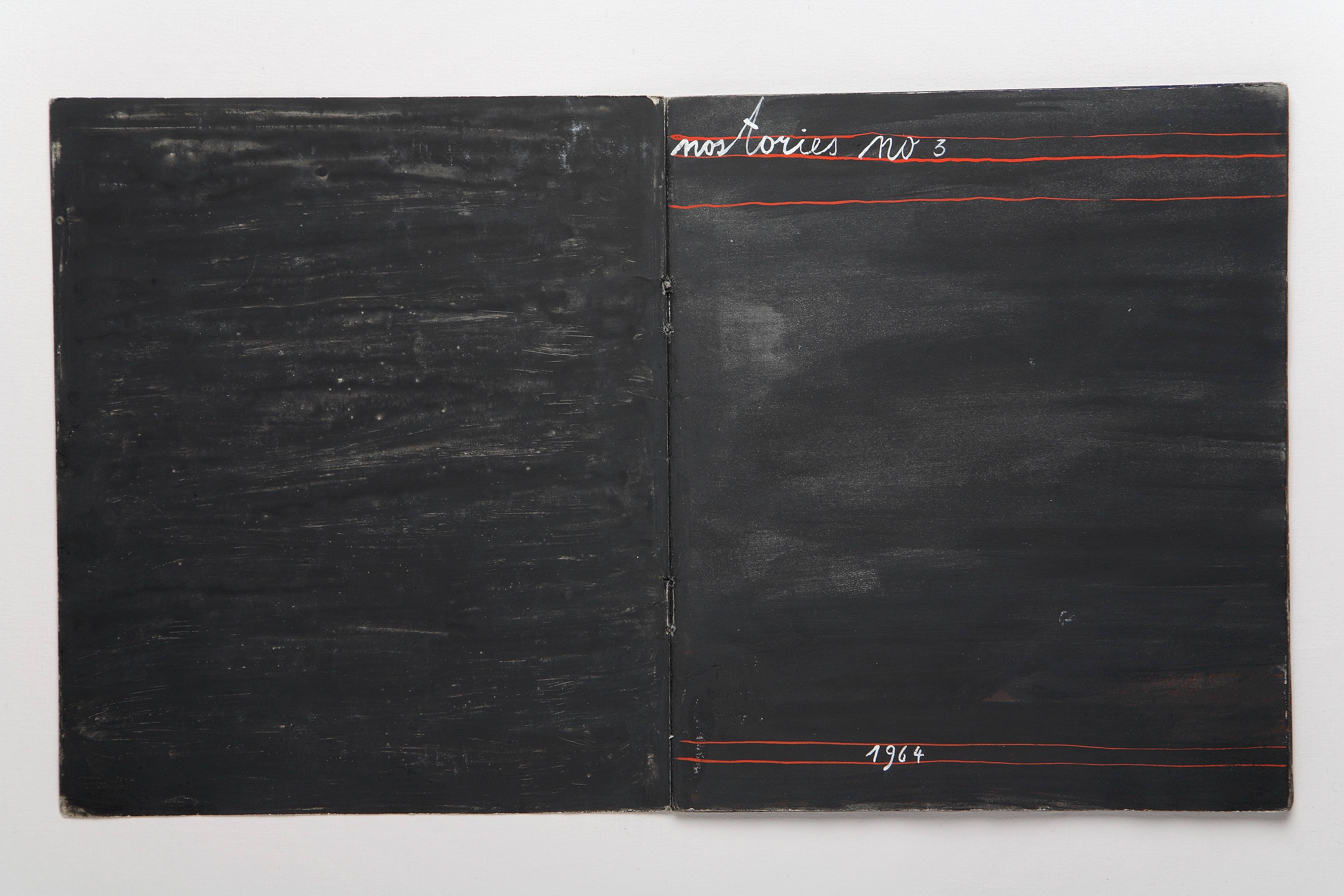

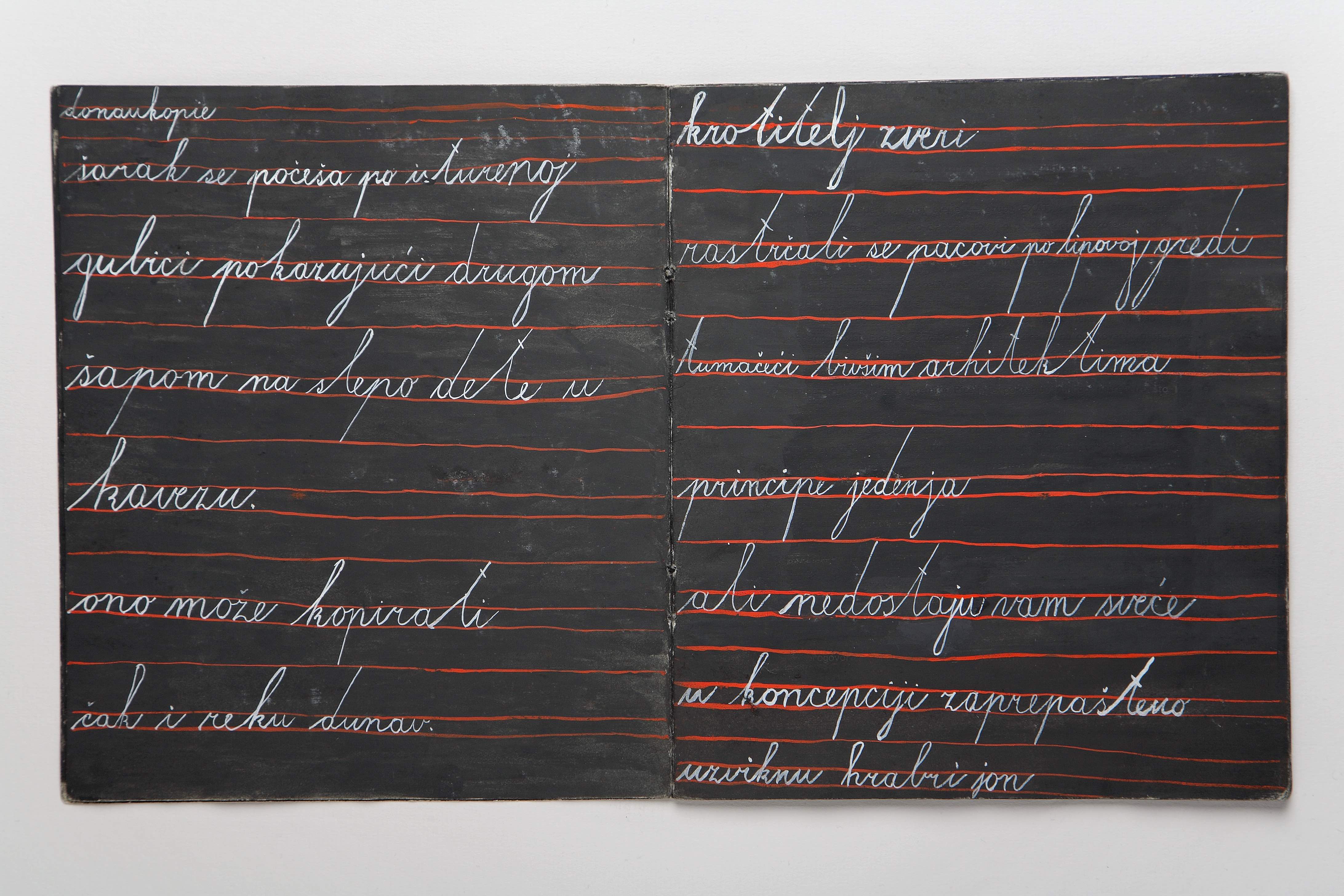

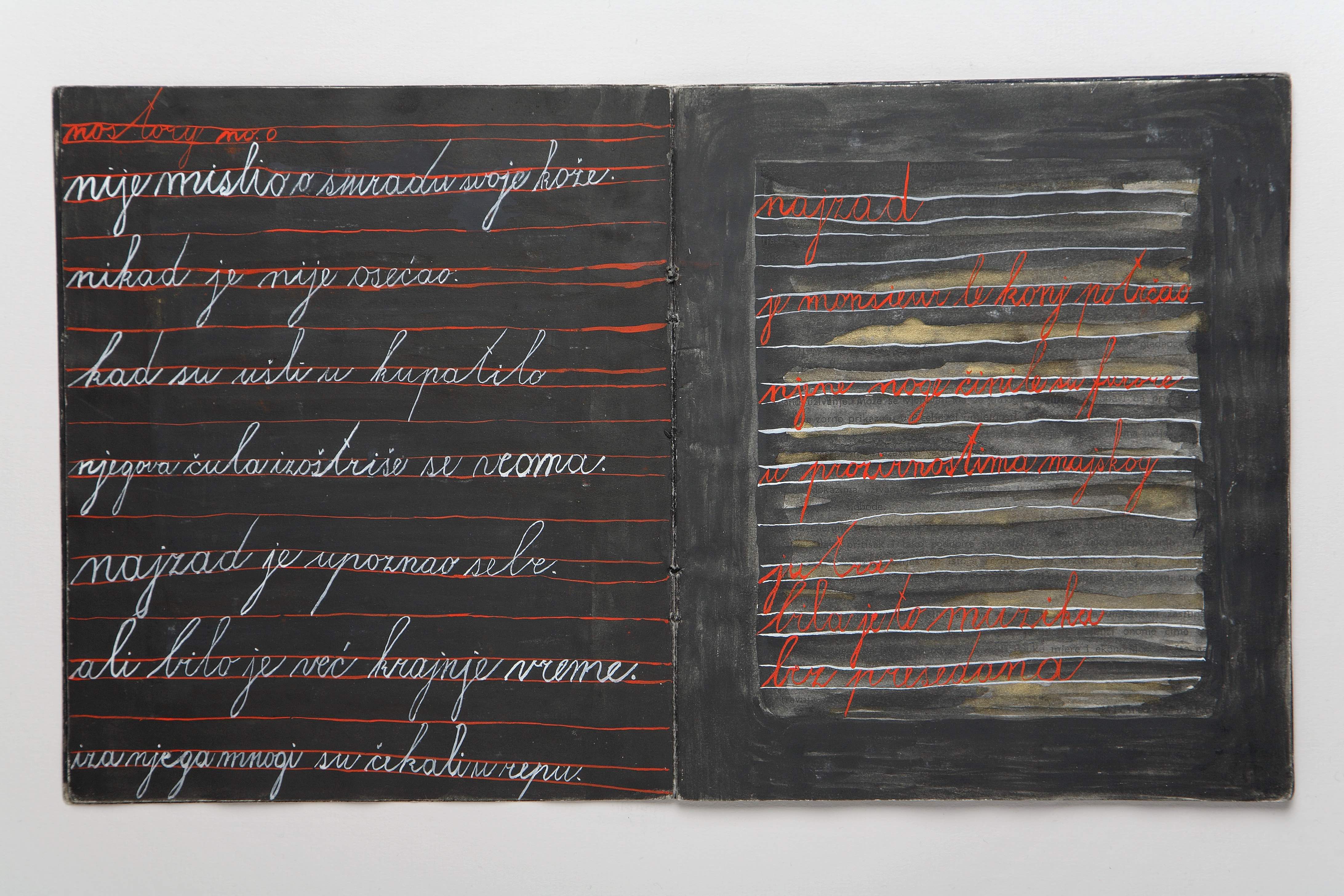

Dimitrije Bašičević Mangelos: Nostories 3, 1964, artist book, courtesy of Mario Bruketa

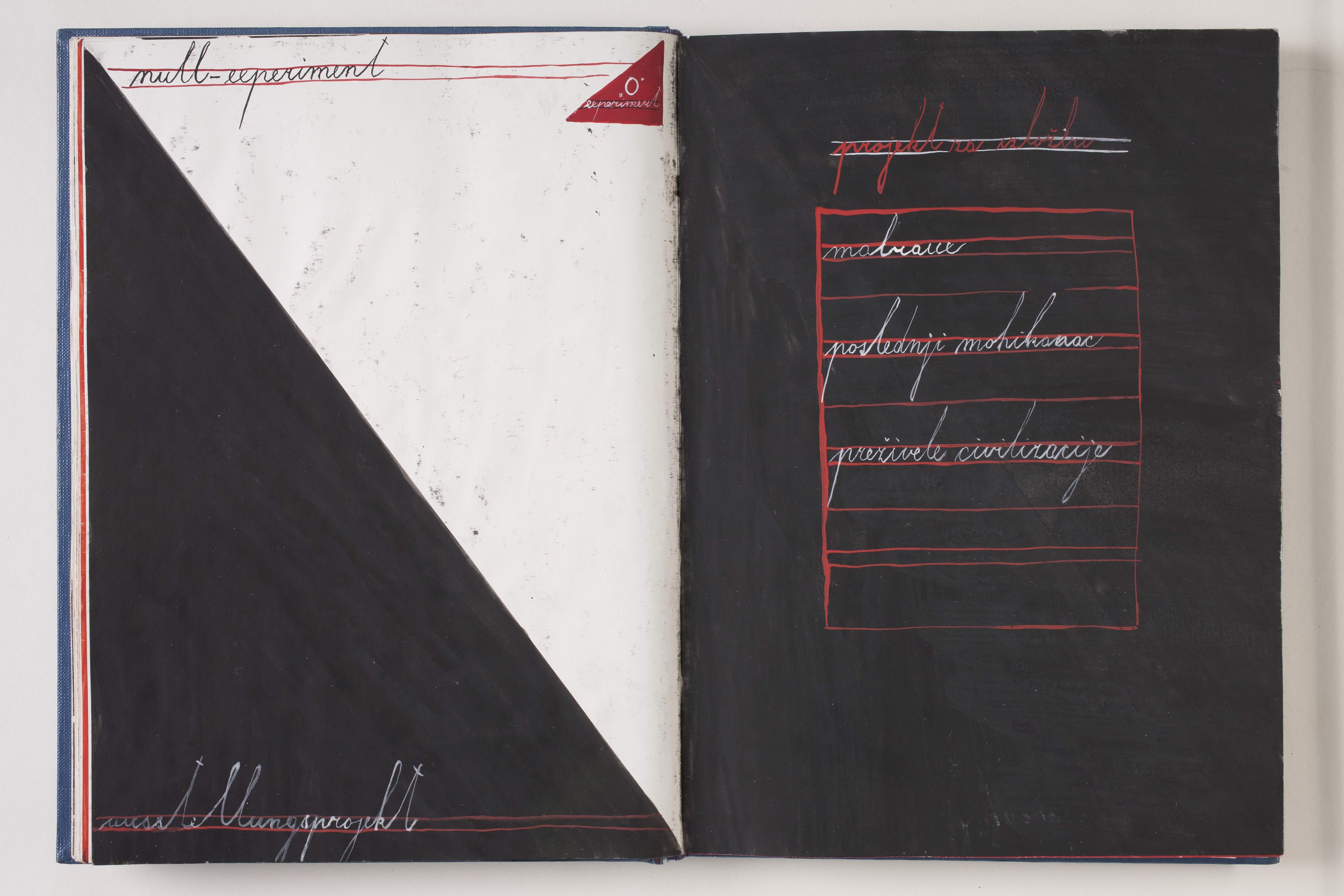

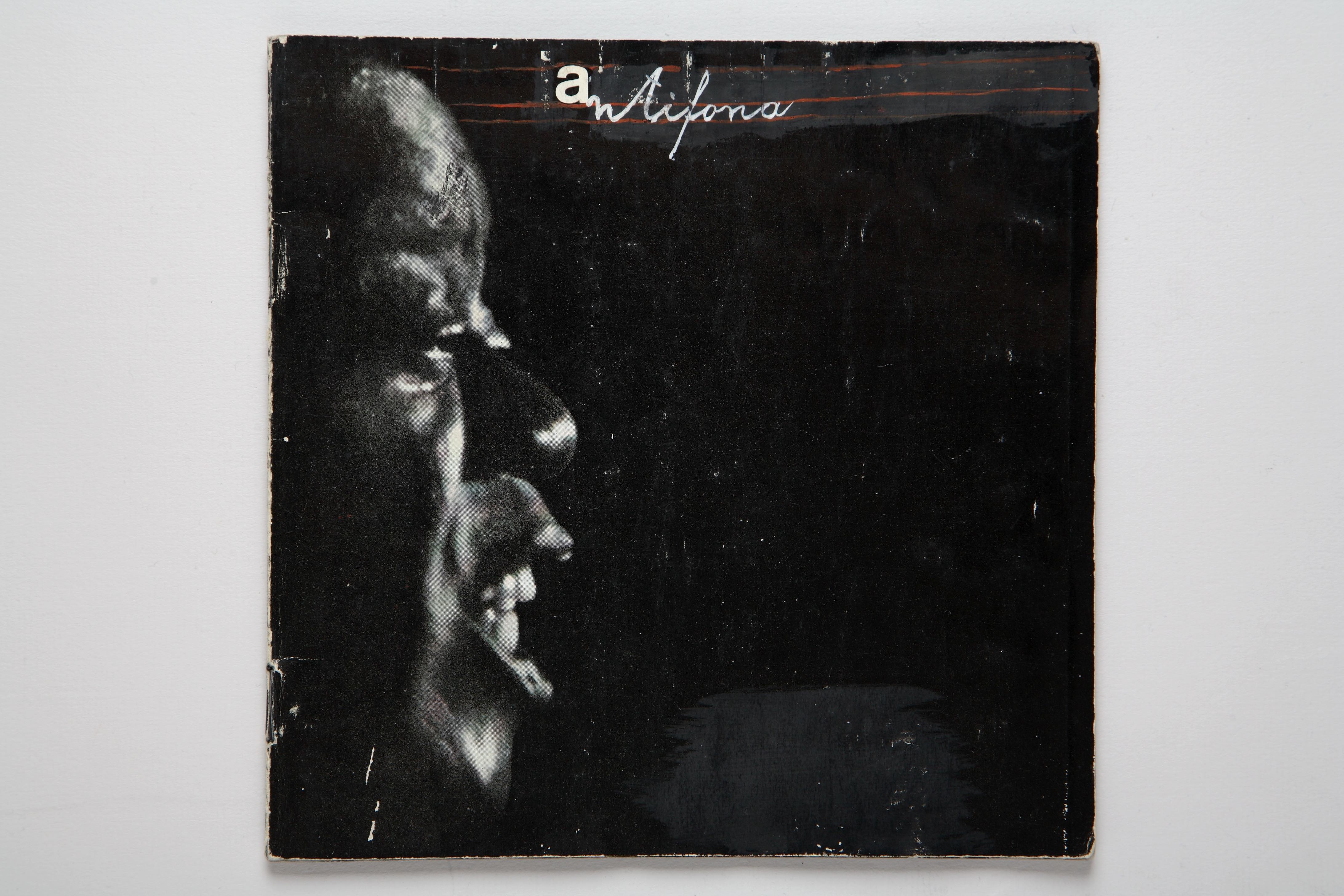

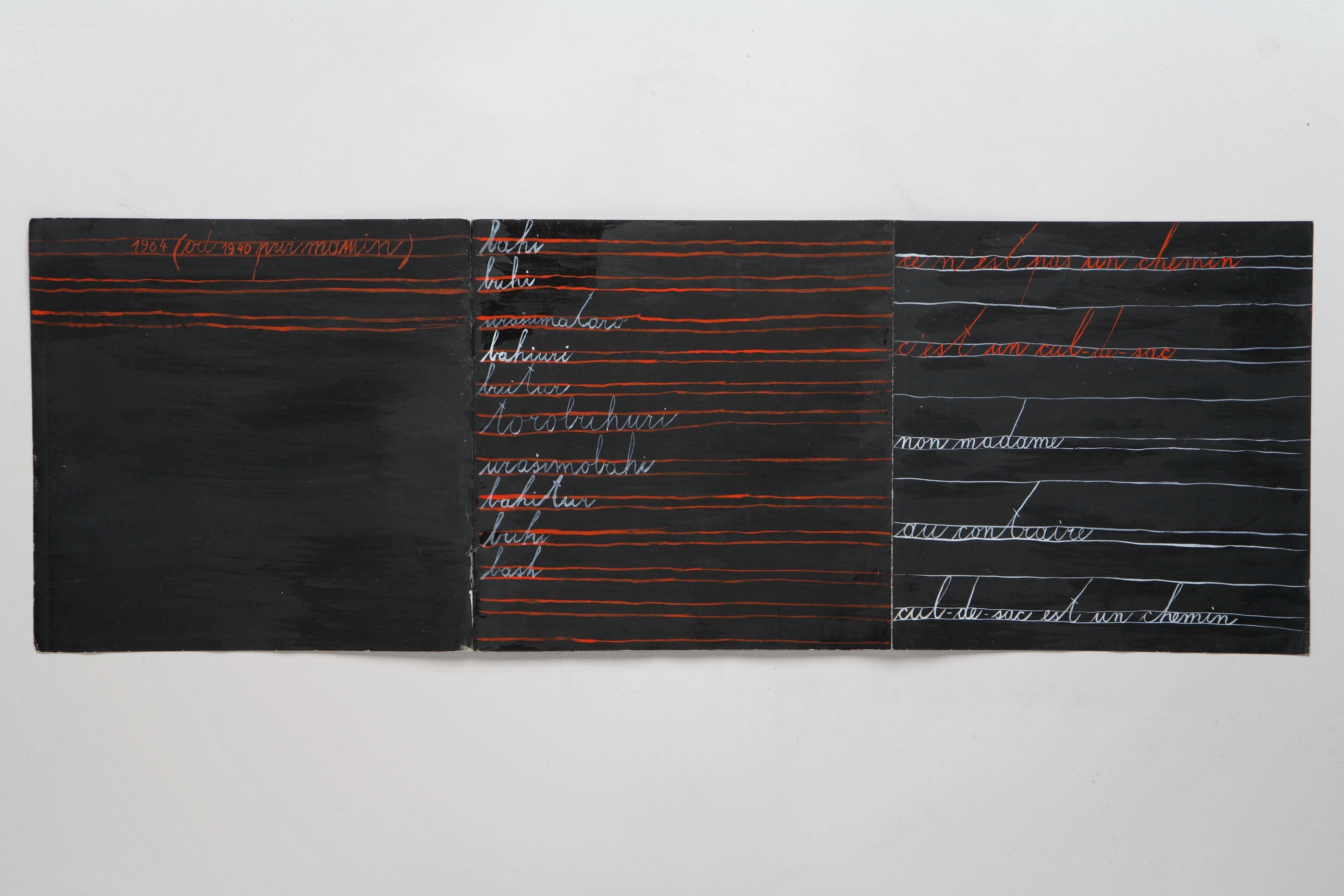

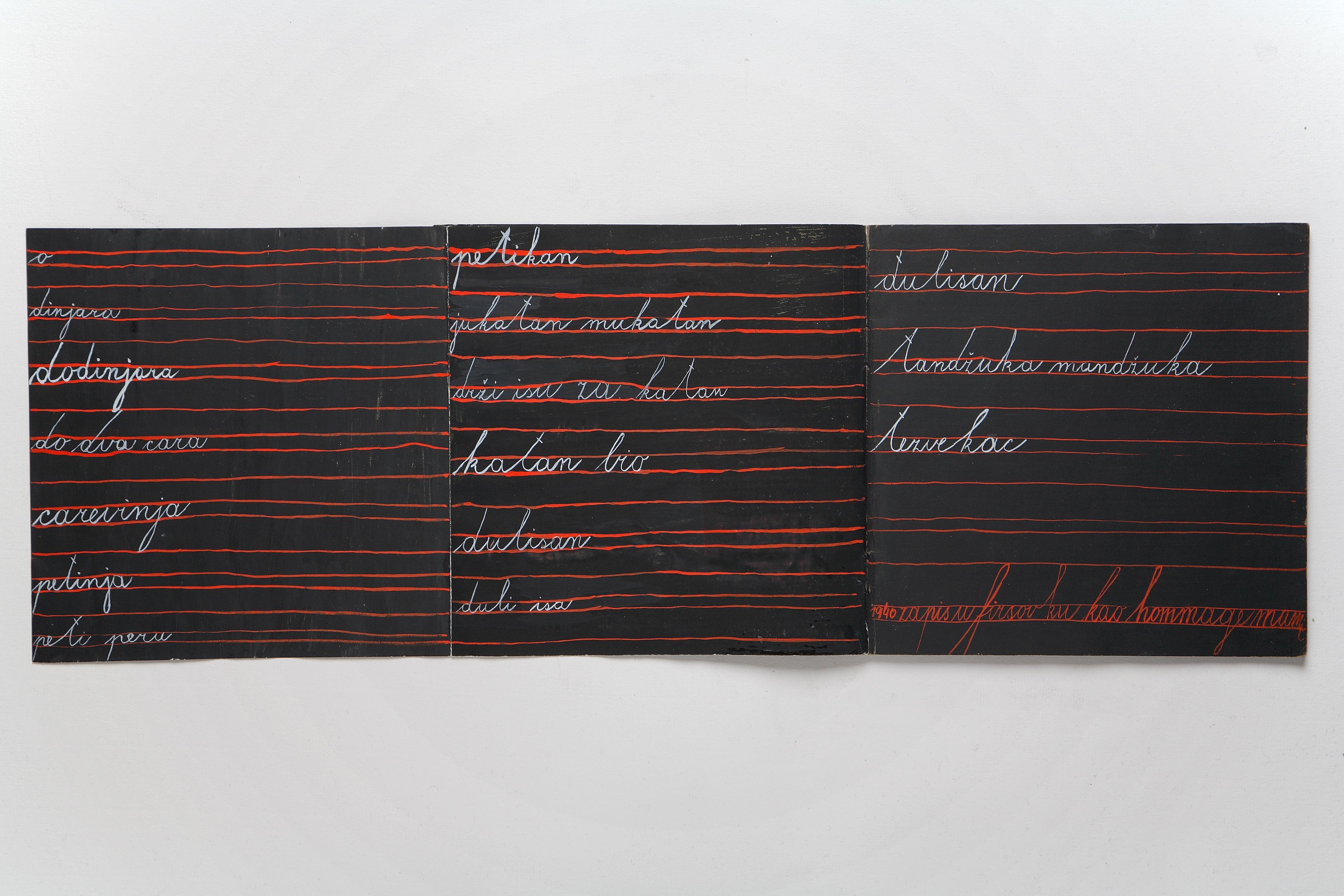

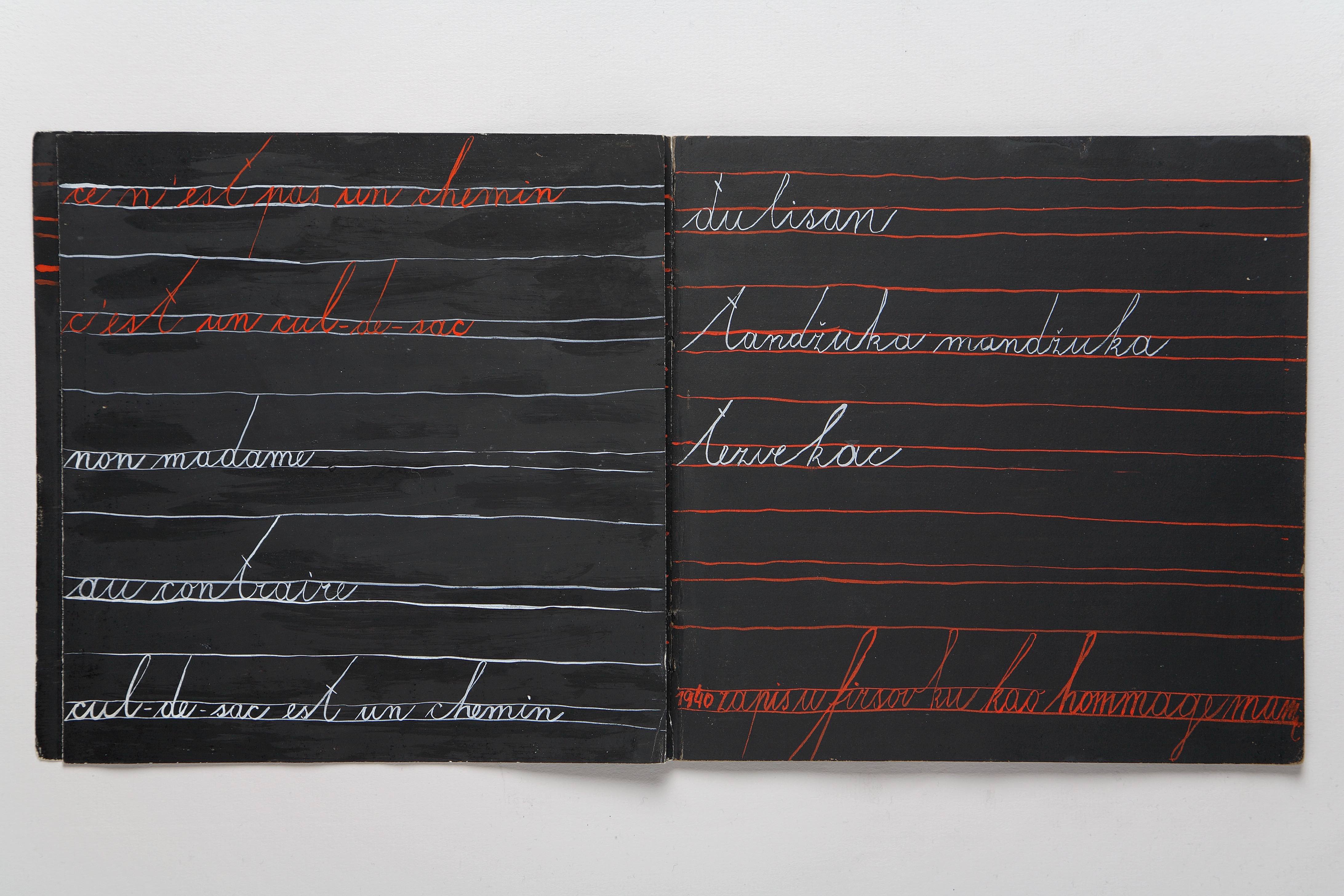

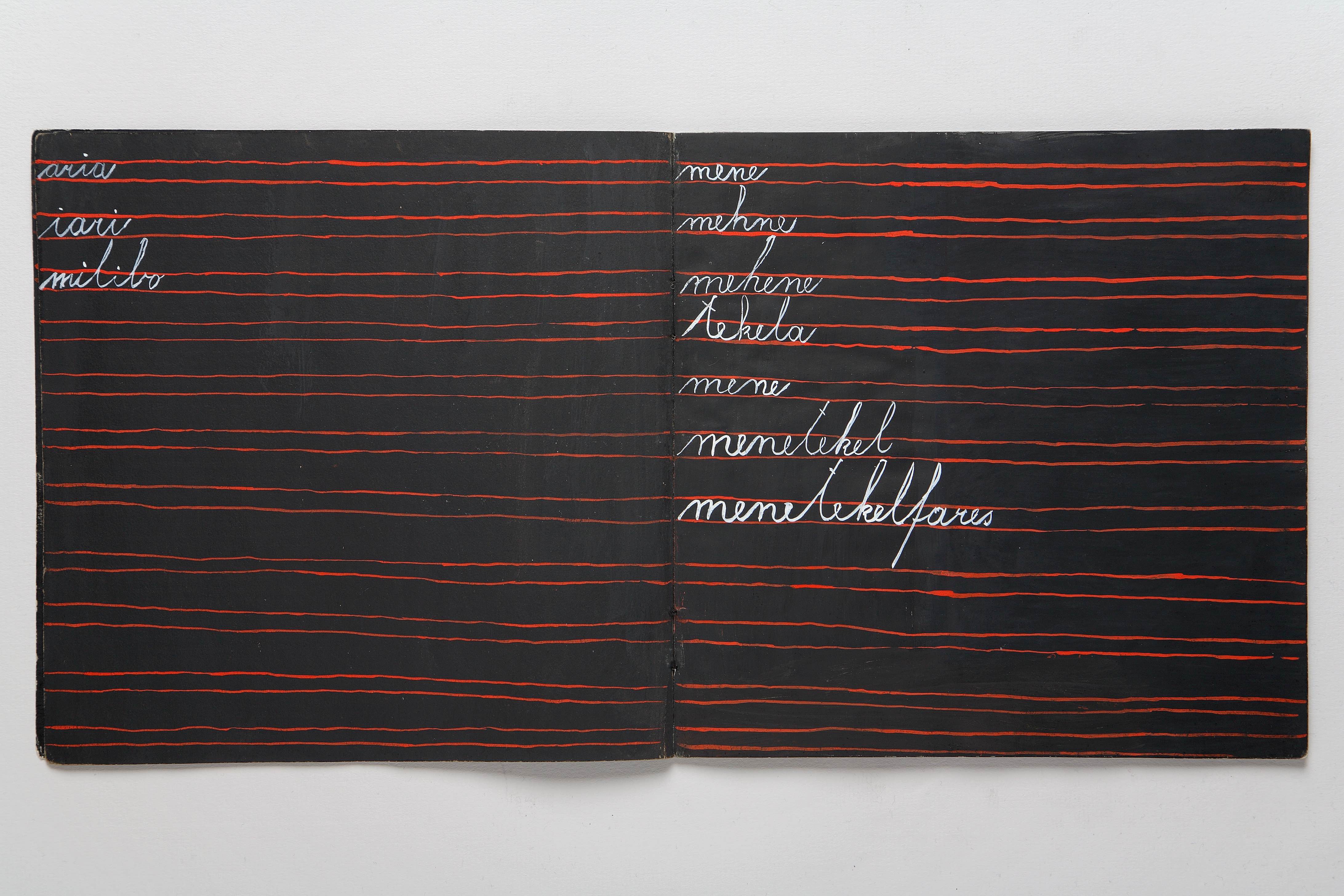

Mangelos operationalized precisely this acousmatic voice. During the 1960s, in parallel with the nostories, he produced a series of antiphons in which the sonority, or phonetic rhythm, deprived the written words of meaning. Etymologically, as the practice of answering, the antiphon exemplifies Mangelos’s theorem ‘logos = praxis’. An antiphon is not a practice of speech or language, but a vocal act that eludes linguistics. Its origin is in ancient Greece, while in Christianity it appears as a liturgical musical-vocal form based on repetition. On the front cover of Mangelos’s 1964 antiphon there is a profile photo of Louis Armstrong singing, one of the very few images in his oeuvre. Within the book, among other things, the syllables of the name Ahura Mazda, the supreme deity of Zoroastrianism, are repeated: ‘mazda / ahura / ahura / ahurama / mazda’. Written in white, they run across a double page in which they are a counterpoint to the red text ‘every seven years / protoplasm and all cells / a completely different person / every seven years / it could be quite serious / both temper and personality / theory’. On another page of this antiphon, there are words written in a column: ‘bahi / buhi / urashumataro / bahiuri / buitur / torbobuhuri / urashimobahi / bahitur / buhi / bash’, whose sonority invokes, along with childish blabber, incomprehensible languages, living or extinct. On the next page, there is a text written in French: ‘ce n’est pas un chemin / c’est un cul-de-sac / non madame / au contraire / cul-de-sac est un chemin’ (‘this is not a path / this is a dead end / no madam / on the contrary / a dead end is a path’). Is this the dead end of language at a time of the breakdown of sense? And is there a connection between this dead end and the end of art history, as considered by Dimitrije Bašićević alias Mangelos some ten years before Hans Belting?46 In his manifesto ende der kunstgeschichte, the Eighth Mangelos (1971–77) wrote in tempera on cardboard: ‘ende der kunstgeschichte / wenn die geschichte / unumkehrbar ist / nach der historischen / aufhebung des bildes / ist kein weiterer bild / geschichtliche erscheinung’ (‘the end of art history / if history / cannot go back to / a historical / abolition of painting / no further painting / is a historical phenomenon’).

Dimitrije Bašičević Mangelos: Antifona, artist book, 1964, Courtesy of Mario Bruketa

Written in 1896, Stéphane Mallarmé’s poem Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard (A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance) abolished the poetic image and ended with a metaphor. In its making, homophony paved the way for metamorphosis, and metamorphosis is, at least according to Deleuze and Guattari, the opposite of metaphor47 – which Mangelos had already abolished in his practice of noart. Mallarmé’s poem, first published in book form in 1914, sixteen years after its author’s death, is considered by Julia Kristeva to be the starting point of a poetic language revolution. In it, the phonetic rhythm in which the semiotic khôra resides dissolves what is symbolic, linguistic. Kristeva has identified the activity of the semiotic khôra in the stage that precedes language acquisition in children.48 The visual appearance of letters, words and sentences in Mangelos’s works, which can also be considered in the context of the category of visual poetry, is analogous to the spatial disposition of words in the manuscript of Mallarmé’s poem, their different sizes within the text, and the unspecified reading direction. One of Mangelos’s landscapes has the text ‘paysage / hazard / il n’y a pas’ (‘landscape / chance / there is none’), in which I recognize what is undoubtedly a reference to Mallarmé’s abolition of the poetic image.

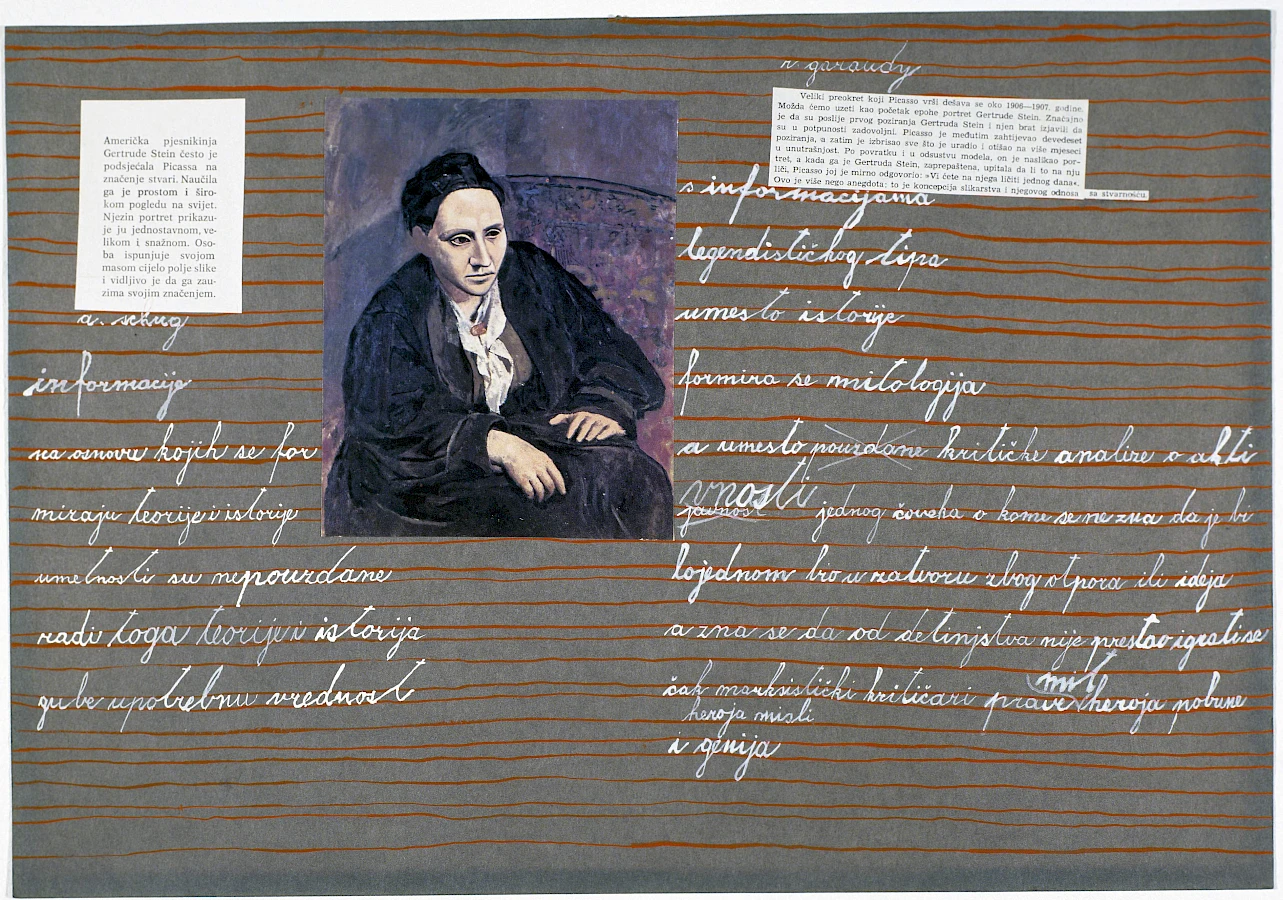

Furthermore, Mangelos’s pulsations, phonetic rhythms in which language bastardization occurs, are akin to the procedures by which James Joyce articulated his untranslatable novel Finnegans Wake, published in 1939. His nostories and antiphons ‘on a path to the source’ or in ‘traffic’ also encounter the phonetic rhythms of the untranslatable sentences in and by which, in the first decades of the twentieth century, having banished similarity from description and arguing that repetition was not a multiplication of the same but an insistence, Gertrude Stein revived words with which she portrayed objects, food, rooms and people. In one of the lecture-performances she gave while touring American universities in 1934, Stein said: ‘Language as a real thing is not imitation either of sounds or colors or emotions it is an intellectual recreation and there is no possible doubt about it and it is going to go on being that as long as humanity is anything.’49 A reproduction of the famous portrait of her painted by Picasso during 1905 and 1906 found its way to the collage American poet Gertrude Stein often reminded Picasso… (c. 1967–72) in which Mangelos counterpointed the meta-language (art history and criticism) of that painting with his own comment, inscribed in a set of lines that connoted his school tablet. A statement Stein made in another lecture describes exactly what determined the origin of Mangelos’s noart, in whatever form, or more precisely dimension, it manifested: ‘In ‘Composition as Explanation’ I said nothing changes from generation to generation except the composition in which we live and the composition in which we live makes the art which we see and hear.’50 Language, for Mangelos, was, as for Stein, an intellectual recreation, a re-creation. That is why it was necessary to negate every image of the world and start from the point where the tabula rasa occurred. Find one’s school tablet and generate a different writing, writing anchored in the ‘composition in which we live and which makes the art which we see and hear.’ Is this the composition called functional thinking?

Dimitrije Bašičević Mangelos: Američka pesnikinja Getrude Stein često je podsećala Picassa / American poet Getrurde Stein often used to remind Picasso… 1967-1972, Courtesy of Ilija & Mangelos Foundation

In a letter to his brother Vojin, written on 22 July 1977 in his apartment at 3 Freudenreich Street, Mangelos wrote:

however this / I must tell you in writing / namely the intellectual development / of your brother has been completed / these days. / that is in principle quite dismal / a point on the iota is still to be made. / that means summarizing in writing / something from the collected / and boiled material. / I have been aware for several years / that the ‘summa summarum’ will be called / ‘functional thinking’. / but I did not have / the details of the construction. / … that same night I made the project construction / for an ‘introduction to the fumiš’ / because I will not be able to write the ‘fumiš’ itself / even in ten years / and the question is whether I will have them.51 / – please save this paper / because all sorts of things get lost with me. / therefore, the ‘introduction to fumiš’ has been planned / as a group of ten essays: / 1. culture and civilization / 2. singing and thinking / 3. practical and theoretical thinking / 4. civilization of manual work / 5. examples of thinking from the upanishads to heidegger / 6. heidegger’s way of thinking / 7. theses on philosophy / 8. machine civilization / 9. meaning and functioning of the world / 10. small encyclopaedia of words without function. / greetings to the whole family / m [inscribed in a set of lines]’52

Vojin Bašičević did save ‘this paper’, but it is not known whether the text of the ‘introduction to fumiš’ that Dimitrije Bašičević (or perhaps the Ninth Mangelos) worked on during the last decade of his life has been preserved, or was ever written at all. More than his response to the Freiburg rector, I am interested in the ‘small encyclopaedia of words without function’. Was it similar to that of Jorge Luis Borges, in which animals are divided into (a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tamed, (d) suckling pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cætera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies?

Dimitrije Bašičević Mangelos: Relations manifesto, acrylic on globe made of plastic and metal, 1971-1977, Courtesy of Mario Bruketa, Collection of Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris