Towards an Aesthetics of ‘Commanding by Obeying’ in Zapatista Audiovisual Material

“Detail of the 1st room while the Battle of Moscow is exhibited”, 2021. Photo credits: Patricia Leguina and Tino Varela.

It must be considered that the aesthetic ruptures were an attempt to organise, based on art, a new life praxis

–Peter Bürger

In 2013, a number of researchers in various disciplines,1 myself among them, began to develop the idea of aesthetics and poetics as structural elements of the political praxis of the Zapatista Movement, an idea we continue to explore to this day.

In various studies, publications, meetings, exhibitions and workshops, we have addressed the field of Zapatista aesthetics as if it were a super-system of meanings, the result of the burgeoning synthesis of Mayan cosmologies from the Chiapas region with the ideologies of the Latin American left typical of the second half of the twentieth century.

“View of the 1st exhibition room, with projections of films that the Zapatistas saw in hiding”, 2021. Photo credits: Patricia Leguina and Tino Varela.

On this occasion, however, and in relation to the exhibition that Massimiliano Mollona and I curated with the support of the Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) at the Centro Cultural La Corrala2 in Madrid, the path followed by this research led me to a new vein of enquiry: obediential aesthetics, a new cultural paradigm.

If we consider the backdrop of poverty, deprivation, neglect and systematic abuse to which the indigenous peoples of southern Mexico were subjected (as are so many others still today in Latin America), we can see the Zapatista Movement is an archetypal example of art at the service of a people engaged in resistance and rebellion, since Zapatismo is an indigenous guerrilla movement with a powerful global impact which, thanks to the political and organisational experience it has acquired3 and in close keeping with local customs and practices, defines the originality characteristic of it.

In aesthetic terms, from the outset (in other words, from those early hours of 1 January 1994) the Zapatistas have presented us with the problem of self-representation as the construction of an image projected into the public light and the media. In the early days of the guerrilla offensive, of the communiqués and balaclavas, the eyes of the entire world press were on the sole target that embodied the whole movement, Subcomandante Marcos. So, as they themselves told us, to ensure the press and civil society turned their attention to them, they constructed Marcos as a hologram that the indigenous communities projected towards the Western world.4 One only needs to look back at the documentaries made between 1994 and 2006 to see that they all focus on him. This public relations plan proved successful.

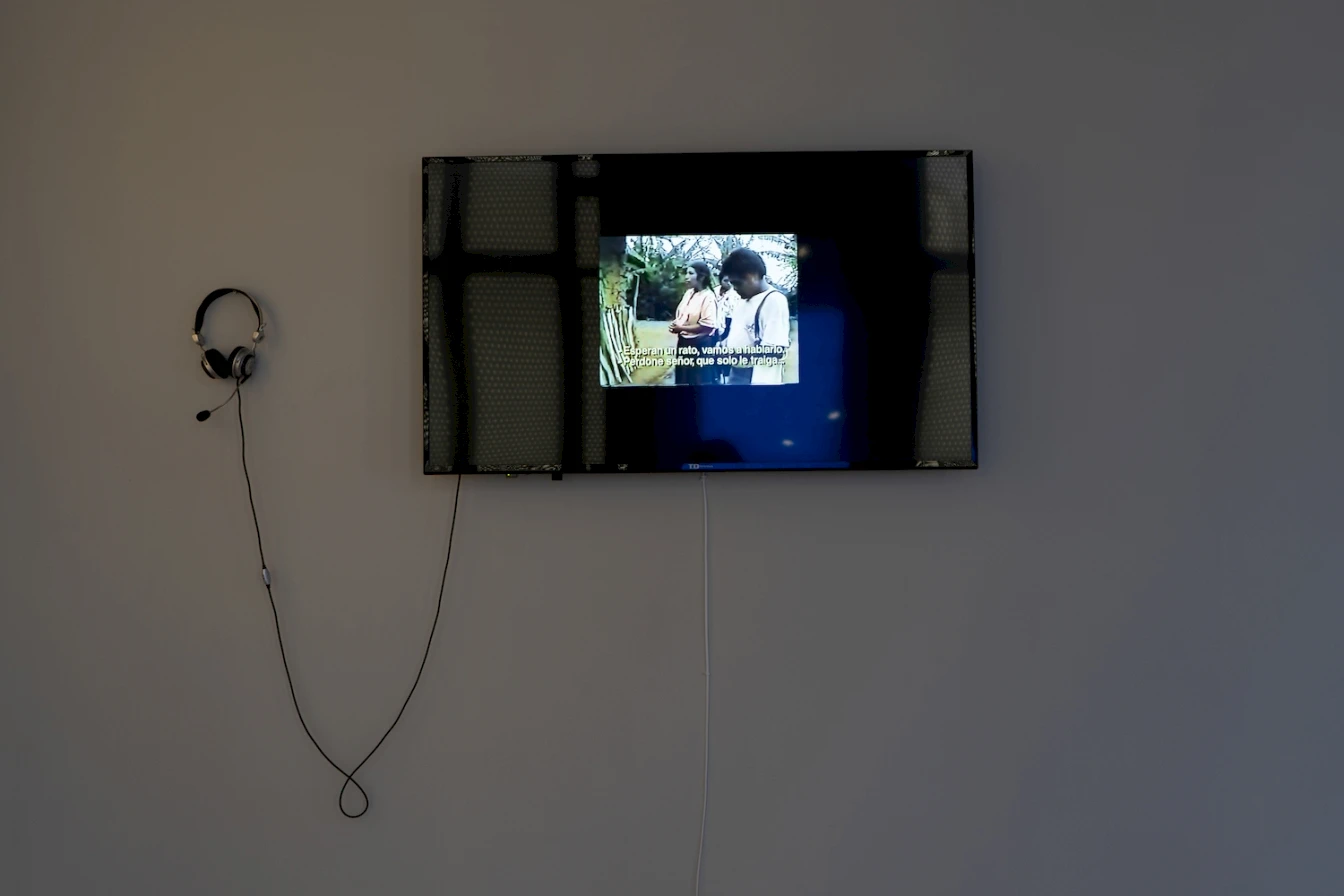

“Video of Tercios Compas: Las Choferas”, 2021. Photo credits: Patricia Leguina and Tino Varela.

This mechanism of seduction on a large scale came from insurgent wisdom acquired over a long indigenous tradition of appropriating images. Whereas Western paradigms are fixated solely on their canons and so render other human and non-human practices invisible, the indigenous strategy of resistance (in keeping with yet surpassing the symbolic disobedience advocated by the Peruvian intellectual Víctor Vich) consists of appropriating the colonial imaginary, giving it a semantic (and often hermetic) turn and hence a utility completely contrary to the intentions of the repressive colonial hegemony.5

While this symbolic disobedience is effective for the purposes of resistance, another mechanism has emerged for organising the meanings of the autonomous Zapatista space: obediential aesthetics, in other words, the aesthetics of the ethics of ‘Obediential Commanding’,6 which Professor Enrique Dussel defines very well: ‘the painter has transformed himself into the subject of an obediential aesthetics and the community is the creative centre of all aesthetics, as it always has been for millennia in every human culture. As the community is the originating centre, we shall term it, unlike politics, the potentia aesthetica. The aesthetic community does not obey the rules of (Kantian) geniuses; rather, it is the potentia that commands (those that obey are now geniuses transformed into obediential artists) and creates, in the final analysis.’7

As we said earlier, aesthetics combined with politics forms the backbone of Zapatismo: the poiesis and the praxis that appear as ‘originality’ in the eyes of the West: demands, communiqués, agroecology, stagings, clinics, tours, schools, festivals, artworks, etc. that convey imaginaries, cosmologies, practices, customs and a radical rebelliousness encompassed in the holistic experience of ‘Commanding by Obeying’.

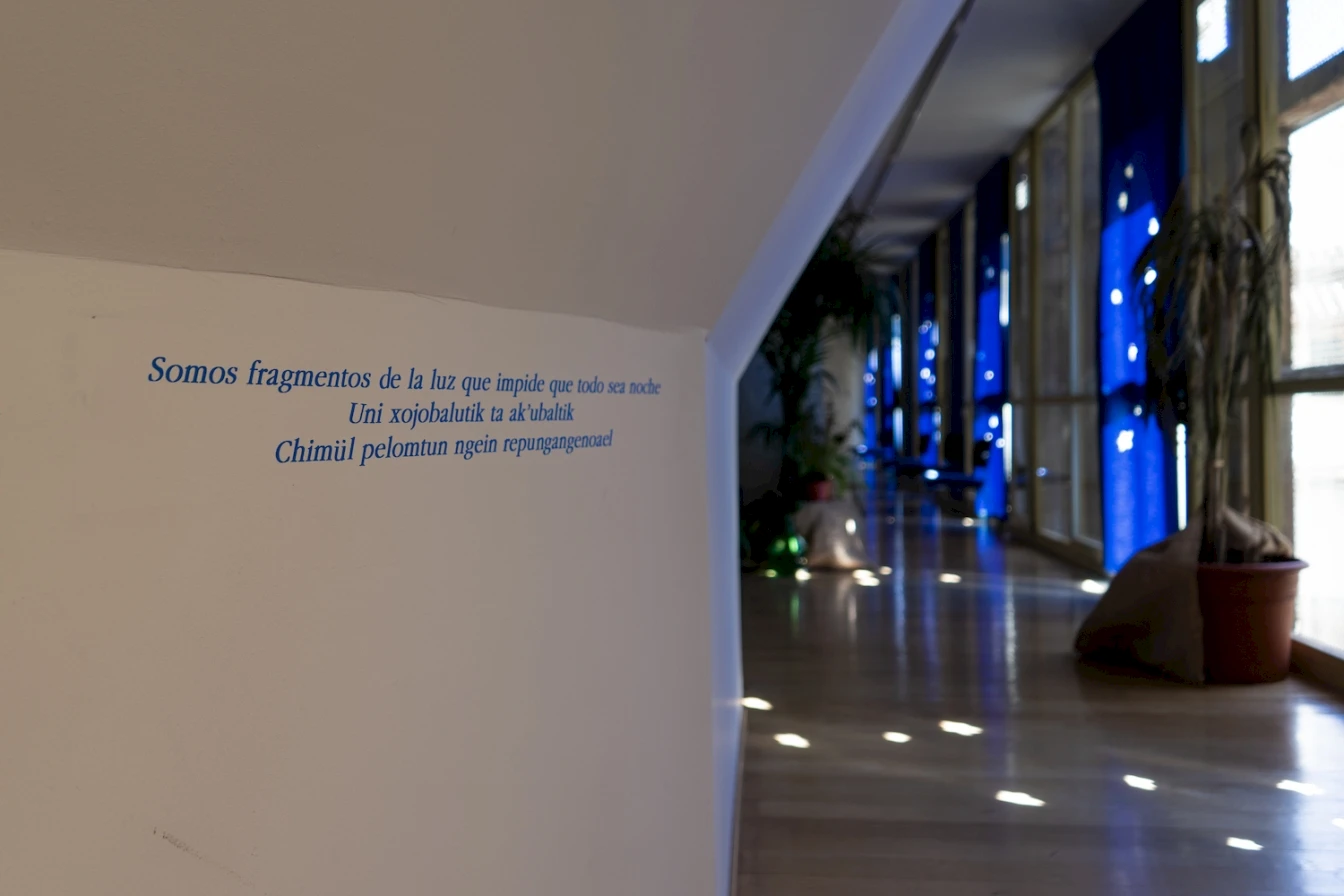

"We are fragments of light that prevents everything from being night." Access to the exhibition, with a title translated into Maya-Tsotsil and Mapuche Mapuzungun. Curatorship of Massimilliano Mollona and Natalia Arcos, 2021. Photo credits: Patricia Leguina and Tino Varela.

In this paradigm, the exhibition We are fragments of the light that stops everything from being night, held in Madrid, was an initial attempt to present one of the communication practices employed by the Zapatistas. In this exhibition, I and my fellow curator Massimiliano Mollona charted the first timeline of Zapatista audiovisual material.

The first context is that of clandestinity. Subcomandante Galeano recalls that in the years when the EZLN (Zapatista Army of National Liberation) was operating in secrecy in the Selva Lacandona jungle (1983–1993), the troops would tell Bruce Lee films to each other, recreating the scenes they had particularly liked, without necessarily following a narrative thread. This happened when one of the militiamen had seen a film and would describe it to the others. Galeano says that in general martial arts films were the most popular among the troops, whereas the Vietnamese film that they entitled Punto de Enlace in Spanish, best reflected the reality of Zapatista peasants. It is not known how Battle of Moscow, sent to them as a gift, was received.

These films were shown in secrecy and only intermittently in difficult, nomadic conditions. They were projected, when that was possible, in 16 mm onto sheets and underwear as a screen, with no soundtrack or subtitles. When DVD and Blu-ray came out in the 1990s, the opportunities to watch a film were few and far between, as this technology was beyond their financial means, plus they were under attack from the army. As the subcomandante says, ‘If we couldn’t watch it when it was bad, we’re less likely to watch it when it’s spectacular’.

Subsequently, the second audiovisual territory fundamentally consists of a period of direct exchanges, mutual learning and close collaboration between EZLN sympathisers and grassroots supporters between the years 1998 and 2008.

To penetrate this terrain of symbiotic fusion, we must tell the story of PROMEDIOS, the US-Mexican audiovisual agency founded in Chicago by Alexandra Halkin. She arrived in Chiapas in 1995 to film a convoy transporting humanitarian aid for the Zapatistas. It was during this process that she detected the militiamen’s enormous interest in learning how to use this technology. There were hundreds of reporters and documentary makers there, but not one of the cameras was in the hands of the troops themselves. Thus it was that, in response to this desire on the part of the Zapatistas and with the permission of the EZLN leadership, as well as financial support from film directors such as Oliver Stone, the idea of founding PROMEDIOS was mooted.

Following this, camera and sound equipment began to arrive in Chiapas, as did audiovisual instructors, most of them Mexican, committed to training the Zapatistas in analogue and digital video making, postproduction, sound, satellite television and internet access. Over the course of its ten-year-long existence, PROMEDIOS taught hundreds of Zapatistas keen to acquire skills in recording and communicating their own processes, as they saw video as another defensive weapon to counter the attacks by the army, paramilitaries, government and big landowners. Their works, made during times of struggle, portray the collective efforts made in agriculture and coffee growing, autonomous education, the involvement of women, traditional medicine and the history of the struggle for land, among other issues.

“Fiction Film by Promedios: The Curandero de los Altos de Chiapas”, 2021. Photo credits: Patricia Leguina and Tino Varela.

“General view of the 2nd room, with videos of Promedios and Tercios Compas”, 2021. Photo credits: Patricia Leguina and Tino Varela.

These examples tell of the empowerment of the Zapatistas thanks to their increasing skills in using this technology. However, it also reveals one of the most important challenges for the PROMEDIOS instructors: the ‘coloniality’ of audiovisual language, in other words, the language associated with the imposition of a type of gaze that obeys the aesthetic and conceptual canons characteristic of the global north – the paradigms of power that emerged as a result of colonialism. One of the problems that some of these instructors faced was how to convey technological knowledge without this in itself being a formal predisposition towards the dominant structure of communication. In this case, the danger was potential interference in the Zapatista peoples’ ways of seeing and feeling; the reproduction, in other words, of a white, patriarchal, individualised and bourgeois subject. Moreover, it should be noted that the constant search for congenital authenticity in indigenous realities and productions is a response to the fascination based on the construct of a specific group as the racialised ‘other’, and hence also falls within the realm of coloniality.

When the Zapatistas closed their doors in 2008 to members of NGOs and international charitable organisations so that they could build their own autonomy without intermediaries, they embarked on an intensive period of making audiovisual material within their communities.

The videos now being made by Zapatista video promoters among grassroots sympathisers (known as ‘Tercios Compas’, the Zapatistas’ media agency and translated into English by them as the ‘Odd Ones Out’) are edited and distributed by the communication centres of the Caracoles Autónomos (small autonomous regions) and on the internet.

This work is done in optimal material conditions, using HD video cameras, live sound equipment and free editing software. Nevertheless, the contextual conditions remain difficult: the frequent lack of electricity, poor internet connections in communities and hacking by the Mexican government.

However, the decolonisation of audiovisual language has begun among the Zapatistas themselves and is not halting. As a result, outside viewers’ narrative, editorial and time-related expectations are constantly challenged: the Zapatista audiovisual material produced by their promoters constitutes a poetics of resistance in that it dismantles the previous cinematographic language that was used to narrate Zapatismo to the world in the documentaries made by the Western industry and refuses (in its times, modes, shots, movements, sequences and accounts) to fall into line with industry standards and fashions.

The poetics of the contemporary Zapatista audiovisual is that of an aesthetics in a nascent state, currently at a degree zero of language: it is a reflection of the ways in which the story of the Zapatistas was previously told and a linkage with the film language which, as they themselves have announced, will necessarily develop in the future as their autonomy grows.

“View of the 3rd room with the projection of the film by José Alfredo Jiménez: Acteal, 10 years of impunity and how many more?”, 2021. Photo credits: Patricia Leguina and Tino Varela.