Life has made them ill, they are victims of a strange illness called pressure, disillusionment, disgust, called – dare I say it? – FEAR. But... who said fear?

(Virgilio Piñera, Presiones y diamantes, 1967)

According to a widely told story, Cuban writer Virgilio Piñera publicly declared his fear during one of the meetings at the National Library of Havana in June 1961 that gave rise to Castro's famous speech "Words to Intellectuals", which would consequently frame Cuba's cultural politics under the doctrine 'Within the Revolution, everything; outside the Revolution, nothing.' Guillermo Cabrera's account of the incident is the most poignant and frequently repeated version. During one of these gatherings of artists and writers chaired by Fidel Castro following the censorship of the film P.M., ... 'suddenly the most unlikely person, all timid and hunched, stood up looking as if he were about to run away, stepped up to the speaker's microphone, and said: "I'd like to say that I feel very afraid. I don't know why I feel this fear, but that is all I have to say."'

Perhaps these were not his exact words; perhaps they are mix of the courage shown by Piñera, the memories of Cabrera Infante, and the desire of those who invoked them like a charm in the decades that followed. In any case, the image of that fragile body taking the floor and speaking his fear took on the status of truth among us. As the author of Vidas para leerlas recalls, Virgilio Piñera expressed what many others felt but did not dare to state publicly. In a small gesture, in a couple of sentences, the almost inaudible murmurings of anxiety, moods and whispers were expressed in the form of public discourse.

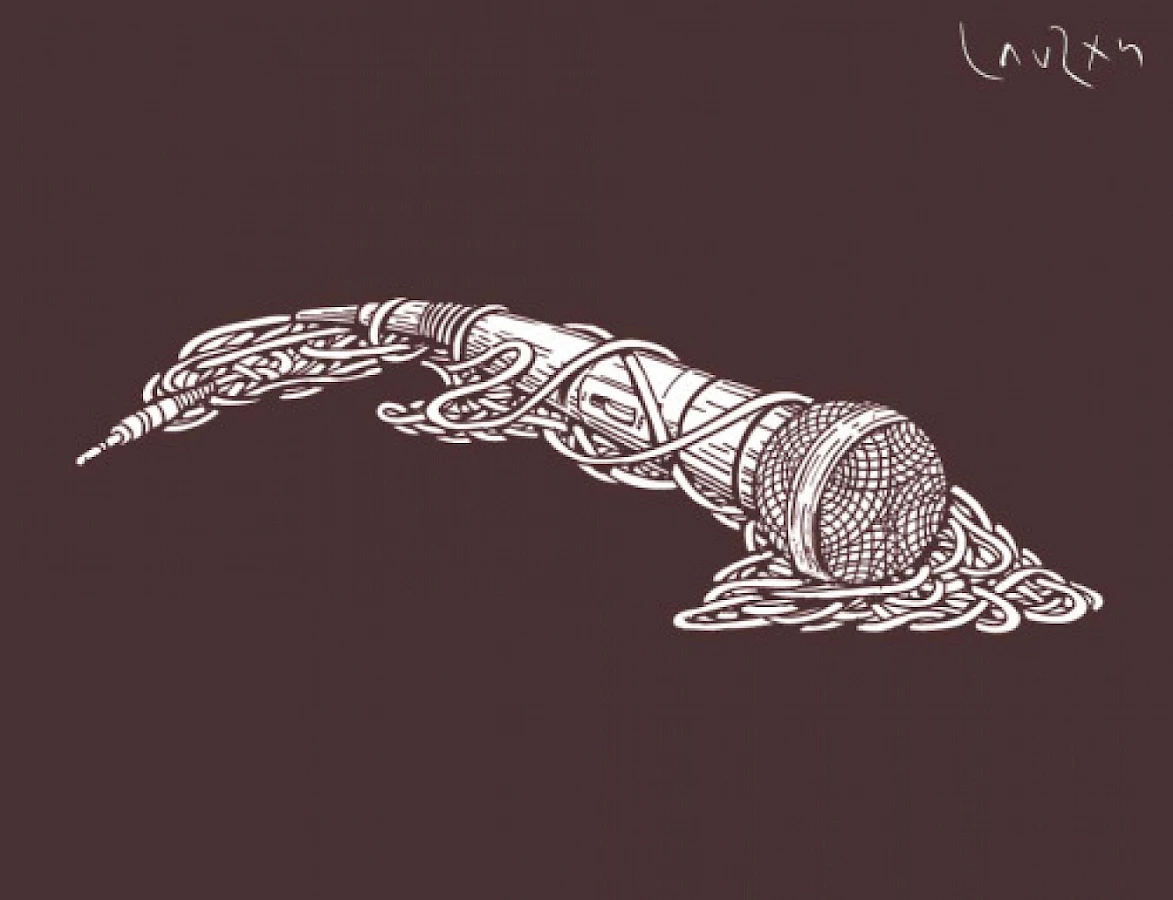

I allow myself to imagine a related story, in which the microphone, accustomed to passionate speeches and ovations, suddenly froze as it amplified the word 'fear'. Stowed away in a corner of the library, more than five decades of dust settled on its case before a new impetus invited it to take a few steps outside of its lair, into Plaza de la Revolución. Our protagonist never made it out into the square on 30 December last year, but fiction allows us to revisit certain connections between the cultural field and political power in Cuba. A different set of cultural policies would probably have been implemented if those gatherings in 1961 had given rise to words with intellectuals rather than words to intellectuals.

We are now far from that moment of intense negotiation when many of the artists and writers at the National Library shared a forthright support for the revolutionary process. As the bolero says, 'nothing remains of yesterday's love...', what little support remains now is hardly forthright and by no means revolutionary. After many of its members fled into exile or hideouts, the arts community's official relations with the authorities are now down to little more than stale cultural bureaucracy and a few well-known figures who may or may not be convinced but are certainly not very convincing. At this stage, the field of negotiation is looking more like a stagnated game board, where each piece knows its allocated place and the narrow margins it can move within.

But let's go back to the story of the microphone that tried to break out of the art scene and make itself heard in a more public arena, in the Plaza itself. As we know, neither the microphone nor Tania Bruguera made it to the supposed 'agora' on 30 December, because she was arrested by the State Security Forces. Meanwhile, rumours of a 'dissident artist' grew. Given the lack of news in Cuba's official media outlets, the visibility of Bruguera's call for participation and the effects it unleashed has depended on blogs, independent newspapers, publications in exile, the international press, and social media. And in view of the local art community's lukewarm support, counter-information groups and political activists have stood by Tania during her long process in Havana.

Practices that are considered 'activist' in other contexts are 'dissident' in Cuba. Activists are denied the political agency that could emerge through interaction with other similar actions or movements. Dissidents are publicly identified, discredited, and criminalised in worn out operations of social and symbolic isolation. The Cuban government has zealously exerted control over language use, so that terms such as 'human rights' have become unmentionable. And the epithet 'citizen' is now used only by police officers addressing a suspect or demanding documents. According to this logic, we are only 'citizens' in relation to a certain presumption of guilt.

It is thus unsurprising that the official vocabulary has replaced 'activism' with 'dissidence', a notion that, Wikipedia tells us, was used particularly in reference to the Stalinist purges from the 1930s onwards, and in Eastern Europe after World War II. In an essay about Soviet dissidence, I found a further clarification of the term, for which The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1993) adds a new meaning: 'A person who openly opposes the policies of a totalitarian regime.'

I believe that Tania Bruguera's action needs to be understood in the framework of the long history of the relationship between art and activism, as a practice that gives precedence to social action. But I think that it would also be fruitful to occupy the idea of artistic dissidence. It seems to me that the concepts of 'political art' and 'critical art' are understood very loosely in today's Cuba. They can include anything from somewhat subversive gestures to political commentary transformed into the innocuous style of the market. Instead of that safety zone with stipulated limits and transgressions, the notion of dissident art could draw attention to the relative lack of artistic projects that openly oppose the politics of a totalitarian regime. Instead of avoiding the term dissidence and acquiescing to its official criminalisation, I suggest reclaiming it and affirming the radical nature of its dissent. And its radical fear – the fear of the writer, the artist, the activist, the citizen, the exile. 'I'd like to say that I feel very afraid.'

Translated from Spanish by Nuria Rodríguez Riestra