Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

In a dispatch from ‘Climate Forum III. Poetics and Operations’, curator Abril Cisneros Ramírez considers the entangled relationship between grief and what she terms ‘volume’, that came to the fore in the session ‘We, the Heartbroken’, led by artist and death researcher G and curator Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide.

There is no speaking about grief without speaking about volume. In the opening scene of The Human Mourning, José Revueltas describes death as sitting on a chair, waiting to enter the body of an ill young girl.1 As she sits, her volume morphs, changing colors. Here, death is not dying but the materialization of the father’s grief – occupying space, resting on a surface – in the moment he fully realizes his daughter is going to die.

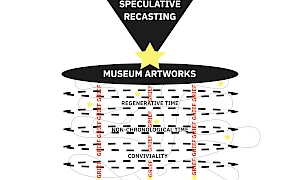

Revueltas' description buzzes in my head, not only because it captures the moment grief becomes physically tangible but also because it pins down the exact instant the possibility of loss emerges – grief does not appear when we lose something, but rather when we recognize loss as inevitable. I have returned to this passage lately, particularly after attending the last session of the ‘Climate Forum III: Towards Change Practices: Poetics and Operations’. Curator Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide and multi-hyphenate artist G presented recent research developments from Regenerative Time – one of four research threads in the upcoming collection presentation at the Van Abbemuseum, that, among other themes, explores how death can figure in a heritage institution.

William Hogarth, Time Smoking a Picture (Detail), 1761, etching and aquatint.

And how can death figure in an institution that promises immortality after works are acquired for the collection? If objects enter a museum collection to live forever, must they not die first? Are archives not our graveyards? Like Revueltas’ text, G’s practice is generative in relation to these questions. Her work explores the volume of grief and its many expressions – the shape of absence, the gesture of contouring what is lost. Yolande’s practice, in turn, often deploys speculative narratives as a tool for recasting artworks away from traditional readings – away from claims of universal value, asserting that history is always negotiated. Yolande has invited G to develop, alongside the museum’s conservation team, an addendum to the existing conservation protocol, based on a series of case studies that explore the many ways (beyond material decay) in which an artwork can ‘die’. Additionally, G is to score a series of ceremonies to both celebrate and mourn art works, and to mediate this transition – attention to ritual insists that grief cannot be expedited.

Within the framework of a heritage institution, the task the project brings forth has both research and speculative latitude. A regenerative approach to time invites an expanded understanding of objecthood, recognizing that artworks can die means acknowledging that they also live – that they have lovers, detractors, and relationships unfolding over time, punctuated by ceremonial appreciation. And it involves a structural questioning of the museum’s collecting practices, which lean toward accumulative preservation as a means of denying mortality. Is this refusal to let go itself a form of grief? Is there potential for renewal in the process of release?

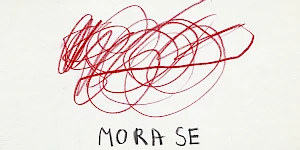

WHAT WOULD IT BE IF THE THINGS YOU CANNOT SEE AND ONLY FEEL WOULD BE IN 3D, 2024, (Work in progress), G's Studio, EKWC. Courtesy the artist.

Attendees at the online presentation at the Climate Forum III were asked to bring an object they felt represented them and were willing to let go of. In a previous in-person edition of the presentation these items were laid on a table. When reminded that they might actually have to part with them, attendees quickly reclaimed what they couldn’t afford to lose. When projected onto the logic of conservation work, this anecdote prompts a reflection on what loss can trigger. Even as they care for objects, conservators are perpetually grieving them. Grief must sit in the conservator’s chair because, in order to prevent possible loss, their task is to assume that loss is always possible, to search for evidence that death is a diligent creature.

Conservation, then, is inherently speculative labour, operating in the realm of preventative measures for a future change of state. Or as Jane Henderson observes, much of conservation work is guided by the question: ‘Is my object being damaged in a way I currently cannot see, but someone might detect in the future with equipment I don’t yet possess?’2 If successful conservation delivers benefits for the future, how are these objects alive in the present? May we, propelled by anticipatory mourning, deprive our artworks from living a rich public life?

G, ART, 2024, video, 3 minutes 20 seconds. Courtesy the artist.

And yet, speculative vigilance collides with the growing burden of accumulation in a shrinking museum storage space. G plays a run and gun video, musicalized to drum and bass and shot at the museum’s storage, where stacked crates tower over the cameraperson in a mazy configuration. From this paradoxical articulation follows the project’s critique of the value system sustaining the presumed common horizon of cultural heritage. What feels easier to let go of? What do we rush to retrieve from the table? Who stands behind “we”? To uncommon histories we must uncommon futures, says Yolande – who are we keeping all this for? Regenerative time calls for a conservation practice that holds as much as it releases, cradles transition, belly laughs while mourning and allows itself some time. If only a minute. If only an hour. If only a day. For all ages. 3

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

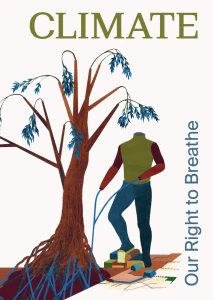

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–tranzit.ro

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

–SALT

Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ is a series of sound installations by Özcan Ertek, Fulya Uçanok, Ömer Sarıgedik, Zeynep Ayşe Hatipoğlu, and Passepartout Duo, presented at Salt in Istanbul.

-

–SALT

Sound of Green

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ at Salt in Istanbul begins on 5 June, World Environment Day, with Özcan Ertek’s installation ‘Sound of Green’.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Open Call: Research Residencies

The Centro de Estudios of Museo Reina Sofía releases its open call for research residencies as part of the climate thread within the Museum of the Commons programme.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

Related contributions and publications

-

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideThe Climate ForumClimate -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoThe Climate ForumClimate -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloThe Soils ProjectClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoThe Climate ForumClimateHDK-ValandEN es -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin Pogačar... and the Earth alongClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

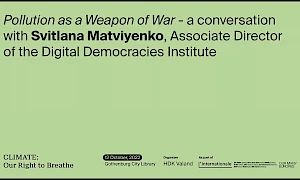

Pollution as a Weapon of War

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimate -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

ClimateThe Climate Forum -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosThe Climate ForumClimate -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifThe Climate ForumClimate -

Pollution as a Weapon of War – a conversation with Svitlana Matviyenko

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Françoise Vergès – Breathing: A Revolutionary Act

Françoise VergèsClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Ana Teixeira Pinto – Fire and Fuel: Energy and Chronopolitical Allegory

Ana Teixeira PintoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Watery Histories – a conversation between artists Katarina Pirak Sikku and Léuli Eshrāghi

Léuli Eshrāghi, Katarina Pirak SikkuClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Indra's Web

Vandana Singh... and the Earth alongPast in the PresentClimateZRC SAZU -

One Day, Freedom Will Be

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoTowards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyInstitute of Radical ImaginationClimate -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoInstitute of Radical ImaginationClimate -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoInstitute of Radical ImaginationClimate -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoArt for Radical Ecologies ManifestoInstitute of Radical ImaginationClimate -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterThe Climate ForumClimatePast in the PresentHDK-Valand -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nkule Mabaso, Nick AikensThe Climate ForumClimateHDK-Valand -

Eating clay is not an eating disorder

Zayaan KhanThe Climate ForumRecette. Reset. Recipes in and Beyond the InstitutionClimatePast in the Present -

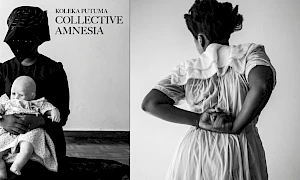

Graduation

Koleka PutumaThe Climate ForumClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaThe Climate ForumClimate -

Soils

ClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanTowards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the PresentClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezThe Climate ForumClimate