Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Mot bakgrund av det pågående folkmordet i Gaza och det flertal folkmord som ägt rum efter andra världskriget och Förintelsen reflekterar Martin Pogačar, forskare inom kulturstudier, kring frasen aldrig mer. Pogačar kartlägger olika bruk av frasen, dess tidsliga aspekter liksom de groteska skillnaderna mellan dess tillämpningar. Genom att avslöja dess performativa tomhet visar Pogačar på ett detaljerat vis hur det ”ett utrymme öppnats för en hänsynslös fortsättning på och acceleration av nekropolitiska och koloniala tillvägagångssätt”. Som motvikt förordar Pogačar en mildhetens politik och en fredlig samvaro som kollektivt politiskt projekt.

För ett barn som växte upp i Jugoslavien under mitten av 1980-talet var framtiden inte någon gäckande dröm.1 I ljuset av de kvardröjande spåren från andra världskriget och det överhängande kärnvapenhotet inbegrep idén om framtiden paradoxalt nog en för alla fredlig och rättvis värld, vilken hade sin grund i befrielsekampernas och de antikoloniala rörelsernas historiska lärdomar och pågående strider.

När jag föreställde mig världen år 2000 såg jag också resor till rymden, flygande bilar och andra klichéer hämtade från det teknologiska framstegets galleri (åtminstone som jag minns det). Omvänt tröttnade jag aldrig på att lyssna till hur det hade varit förr i tiden: hur det kändes att se en apelsin för första gången och bita i den med skalet på, att vinka till ett förbipasserande tåg eller betrakta det statiska flimret från en svartvit TV.

Mest gripande var berättelserna från krigstiden. Min morfar överlevde Gonars, ett av alla (bortglömda) fascistiska koncentrationsläger, och min mormor förvägrades sitt slaviska namn när fascisterna ockuperade regionen Primorska längs dagens västliga gräns mot Italien. Min farmor förlorade sin far i Ravensbrück... full av bävan lyssnade jag till historier om att smuggla hemliga meddelanden genom fascistiska kontrollstationer och grämde mig över att min farfar begravde sin fiol i skogen när han anslöt sig till partisanerna och aldrig hittade den igen.

Sådana minnen från ”kriget” – som gjorde skräcken, våldet och den förestående döden närvarande igen – var utan undantag sammanvävda med solidariska värderingar, respekt för mänskligt liv samt med insikten om att krig och våld inte alls leder till en fredlig lösning på konflikter.

Samtidigt sågs motståndet alltid som det enda rätta att göra när man stod inför ockupation och förstörelse. En sådan hållning var dessutom bemängd med en etik som gick utöver ”blotta” frigörelsen från ockupationen genom att socialistiskt vilja forma en ny och bättre värld.

I efterhand försökte den jugoslaviska socialismen i både tanke och handling åtminstone att göra sin egen tillvaro begriplig i bredare humanistiska termer; den framhöll fredlig samvaro, och är själv kanske ännu ett av de internationellt mest positiva politiska och kulturella projekten och en central beståndsdel i ”historiens största fredsrörelse” och hör till de som ”efter kriget [sökte] alternativ till herravälde och förtryck...och uppfann nya politiska språk för frigörelsen”.2

Aldrig mer

Andra världskriget slutade när ”freden bröt ut”.3 Men freden var inte (och kommer aldrig att vara) jämlikt fördelad. Nya konflikter bubblade under ytan och det blåstes liv i gamla. Populärkulturen gör vissa krig berömda och skymmer därmed sikten för andra grymheter som anses mindre politiskt relevanta och ägnas mindre allmän uppmärksamhet. Det gäller till och med historiska fall av folkmord, såsom det belgarna begick i Kongo, folkmordet på armenierna, och mer nyligen det förhållandevis synliga folkmordet i Rwanda liksom det i Srebrenica, det första som begicks i Europa efter andra världskriget. Nyhetsmedierna har bara ägnat kurdernas, rohingyernas, uigurernas och, återigen, armeniernas lidanden en perifer rapportering. För närvarande överstiger bevakningen av Rysslands invasion av Ukraina, Israels folkmord i Gaza, liksom de eskalerande attackerna på Libanon, den som ägnas andra pågående grymheter, delvis på grund av deras högst volatila politiska och militär industriella insatser.

Efter andra världskriget (åter)gavs ett löfte om att aldrig mer tillåta sådana grymheter och vansinnigheter: ett löfte till våra efterlevande om att för all framtid förebygga ödeläggelse och massmord, att (i god tid) motverka det främmande görande och hat som ledde till mordet på civila judar, romer, slaver, kommunister, homosexuella och andra som dog under Förintelsen, själva sinnebilden för ett industrialiserat lidande och förstörande. Aldrig mer, det kraftfullaste imperativ vi har för att lära oss av och aldrig upprepa historien, både drev på och närdes av den materiella och symboliska återuppbyggnaden av vad den brittiske historikerna Keith Lowe kallar ”den vilda kontinenten” – det vill säga Europa.4

Frasen aldrig mer har dock en längre historia. Som Omer Bartov anmärker användes den först efter ”kriget som skulle göra slut på alla krig” (vilket struntprat) – det vill säga första världskriget – och då i bemärkelsen ”vi ska göra allt vi kan för att förhindra ytterligare5 något som stärkte föreställningar om pacifism och eftergiftspolitik. Men som Bartov vidare påpekar lade man i den tyska kontexten en annorlunda tolkningsmässig tonvikt vid frasen aldrig mer:

Egentligen förlorade vi inte det där kriget. Vi blev huggna i ryggen, så det där kriget måste utkämpas en gång till. Och denna gång ska det vinnas. Omtolkningen av första världskriget i Tyskland leder oss in i den nationalsocialistiska diskursen, in i ett krig som förlorades av felaktiga orsaker och ett krig som skulle ha vunnits.6

I den judisk/israeliska kontexten efter andra världskriget var innebörden av aldrig mer inte ”aldrig mer krig” per se, utan snarare:

”Aldrig mer Förintelsen”. Man säger inte ens ”Aldrig mer folkmord eller massmord”, utan ”Aldrig mer Förintelsen”... [Och om] den aldrig mer ska äga rum borde vi göra allt som står i vår makt för att förhindra det. I själva verket är allt som vi kan göra för att förhindra det rättfärdigat. Detta tillåter en att göra allt man kan eller vill göra om man upplever ett särskilt hot, ett existentiellt hot.7

Avslutningsvis identifierar Bartov ett slags aldrig mer-liknande påbud, även om just en sådan vokabulär inte används:

den kommunistiska varianten kommer i form av antifascismens slogan, det vill säga att nazistiska och fascistiska system alltid måste motverkas och att allt vi gör för att förhindra dem är rättfärdigt... Det är ett slags ”aldrig mer” som ger en dispens att göra vad som krävs för att hindra dem från att förverkligas.8

Lägg märke till att även om den senare förefaller mest öppen och inkluderande till skillnad från de mer utestängande etno-nationalistiska tolkningarna, utmärks den likt alla aldrig mer som Bartov nämner inte bara av brådskan att förhindra framtida krig och folkmord, utan även av det spekulativa rättfärdigandet av våld i namn av att förhindra våld och folkmord.

Aldrig mer?

Som förkunnelse är frasen aldrig mer riktad mot det för gångna: den är ett löfte om att minnas offren och om att förhindra att det som hänt faller i glömska. Som Stef Carps och Michael Rothberg anmärker kan frasen i en sådan bemärkelse ses som en impuls för att minnas och ge form åt ”traumatiska historier över gemenskapers gränser” – rent av som ett verktyg för att ”mellan samhällen överföra empati för andras historiska erfarenheten” med ”förmåga att åtminstone hjälpa människor att förstå tidigare orättvisor, att frambringa social solidaritet och för att skapa allianser mellan olika marginaliserade grupper”.9 Och visst, även om den diskursiva och moraliska särskildhet som tillskrivs Förintelsen stundtals kan skymma andra grymheter eller tona ner traumatiska händelser som kan verka mindre våldsamma, destruktiva eller på annat vis inte anses ”tillräckligt traumatiska”, så tillhandahåller det gemensamma minnet av Förintelsen faktiskt en modell för hur det är möjligt att både tala och forska om andra våldsamma handlingar i människans historia.10

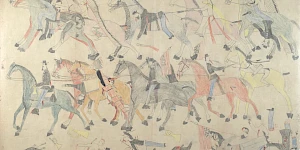

Samtidigt är det huvudsakliga anspråket i aldrig mer framåtblickande: att bidra till utformandet av en annan värld bortom erövring, underordning, massmord och ödeläggelse. Som sådan symboliserade frasen efter andra världskriget möjligheten att integrera en generations historiska trauman och, som en uttalad förhoppning om en fredlig framtid, en radikalt annorlunda efterkrigspolitik samt (populär)kultur. Frasen influerade också avkoloniseringskampernas handlande och ideologier liksom formandet av politiska allianser mellan koloniserade nationer,11 som på 1955 års asiatiska och afrikanska konferens i indonesiska Bandung, där uttrycket ”Bandung-andan” [Bandung Spirit] föddes. Darwis Khudori drar sig till minnes:

För mig personligen representerar ”Bandung-andan” en gemensam önskan om: 1) en fredlig samvaro bland nationerna; 2) världens frigörelse från hegemonin för en given supermakt, från kolonialism och imperialism samt från varje slags herravälde hos ett land över ett annat; 3) jämlikheten mellan raser och nationer; 4) solidaritet med de fattiga, de koloniserade, de utsugna, de svarta och med dem som försvagas av rådande världsordning; och 5) en på människan inriktad utveckling.12

Den alliansfria rörelsen som sparkades igång på ett liknande vis i Belgrad 1981 antog idén om fredlig samvaro som central grundprincip och utvidgade eller försökte därmed att utvidga andemeningen och uppmaningen i aldrig mer mellan människor, nationer och kontinenter bortom Västvärlden.

Var finner vi aldrig mer idag? Och var i denna värld formad av dödande, förstörelse, utsugning och utvinning har den befunnit sig under de senaste åttio åren? Hur kommer det sig att många av de som sitter på makten aktivt bidrar till att nedmontera varje försök att närma sig en fungerande internationell ordning – hur bristfällig den än må vara – av humanitär rätt liksom av andra globala institutioner som skapades för att förhindra världens (åter)barbarisering?

Samtidigt som de sista överlevande, de sista vittnena till och förövarna från andra världskriget dör undan, samtidigt som stater och ideologier kollapsar samt nya uppstår och de geopolitiska förhållandena följaktligen förändras har de värden, drömmar och förhoppningar som härleddes ur ruinerna i allt större utsträckning blivit till blott en formalitet i politiska uttalanden. Som exempel kan vi ta detta uttalande som den tyske ambassadören i Egypten gjorde på Minnesdagen för Förintelsen omkring åtta månader före den 7 oktober 2023:

Det är vår plikt som nation och människor att hålla minnet vid liv och att se till att historien inte upprepar sig. Glöm aldrig, och aldrig mer. Detta blev det överordnade målet för vår utbildning och för vår utrikespolitik. Idag betyder detta att kämpa mot varje form av diskriminering, rasism, antisemitism, anti-islamism och hat som åter är på framväxt i våra samhällen. Detta börjar på samhällelig gräsrotsnivå, i skolornas utbildning samt i lokala och religiösa sammanslutningar.13

Vem är då frasen aldrig mer möjlig att tillämpa på idag? Varför har den blivit en diskursiv trop som endast tillämpas retroaktivt, efter att grymheterna har begåtts? Vilka omständigheter är det som har gjort att den närmast försvunnit eller degraderats, eller snarare, som avslöjat den som ett utanverk?

Aldrig mer – för vem?

Nya former av aggression och krig kan inte längre förstås inom 1900-talets historiska och minnestekniska ramar. På gott och ont kan inte heller gångna krig och ödeläggelser förstås inom ramen för den marknadskapitalism som segrade i och med ”nederlaget” för socialismen som ett frigörelseprojekt, men som sedan dess har blivit till ett cyniskt legitimerande av ett statligt understött våld som säger sig slåss för ”demokrati” och ”frihet”. Hur ärevördiga dessa värden än må vara så präglas införandet av dem i samtida konflikter av ”uteslutanden”, censur, hyckleri, ”alternativa sanningar” och rena lögner, för att nu bara nämna några missbruk av språket (eller bilder för den delen). Som Ursula K. Le Guin påpekat: ”Att missbruka språket är att använda det på samma sätt som politiker och reklamare gör, det vill säga för vinnings skull, utan att man tar ansvar för vad orden betyder. När språket används som ett medel för att tillförskansa sig makt eller tjäna pengar går det vilse: det ljuger.”14

Snarare än ett lugnande medel framstår frasen aldrig mer allt mer som en grotesk politisk lögn. Dess performativa tomhet, emancipatoriska devalvering och selektiva tillämpning exemplifierar hur högtflygande begrepp som frihet, demokrati och mänskliga rättigheter för vinnings skull och detta på sätt som vilar på absoluta motsatser som ”gott och ont” eller ”rätt och fel”. När begreppen används på ett sådant sätt bidrar de enbart till de blodiga, uteslutande, godtyckliga, selektiva och religiösa-mytiska ”verkligheter” som understödjer eller till och med inrättar uppdelningarna mellan dem vars liv är värda att leva och alla andra.

Så är fallet med det pågående folkmordet i Gaza som ut förs av staten Israel,15 vars slakt och rasifierade optik påvisar den närmast från start närvarande selektiva och uteslutande aspekten av den israeliska statens aldrig mer: tre år efter andra världskriget och just efter staten Israels inrättande 1947,16 kom 1948 års Nakba att leda till Palestinas ödeläggelse och till ett omfattande förvisande och berövande av palestinier. På FN:s webbsida ”Om Nakban” står följande:

Så tidigt som i december 1948 begärde FN:s generalförsamling möjligheten för flyktingar att återvända, återlämnande av egendom samt kompensation (resolution 194 (II)). Trots otaliga resolutioner från FN förnekas palestinierna sjuttiofem år senare fortfarande sina rättigheter. Enligt UNRWA är mer än fem miljoner palestinska flyktingar idag skingrade över Mellanöstern. Ännu idag bestjäls och fördrivs palestinier av israeliska bosättningar, vräkningar, landsstölder och förstörelser av hem.17

Trots detta får Nakban begränsat erkännande och uppmärksamhet i västerländska medier och officiell politisk diskurs.18 Som Michael Mann observerar är det som ”gör denna situation unik” att den ”involverar att ett ursprungsfolk påtvingas en bosättarkolonial stat av ett annat folk, ett folk på flykt undan ett folkmord”. Mann fortsätter:

Liberala antaganden skulle kunna få oss att tro att de fruktansvärda erfarenheterna av Shoah skulle göra israeliska judar mer känsliga för andras lidande. Tvärtom tycks många tro att för att överleva som folk måste de till fullo göra bruk av all den tvingande makt som står till buds. Eftersom israeliska judar har den militära och politiska makten att ta arabiskt land tror de flesta att de har rätt att göra så i namn av etnisk överlevnad.19

För att aldrig mer ska fungera har det efter andra världskriget ansetts nödvändigt att omdefiniera systemet för internationella relationer, internationella lagar och avtal, samt att när så väl skett räkna in även de nyligen avkolonialiserade nationerna. I egenskap av den enda aktör som kommer i närheten av att ha den nödvändiga verkanskraften har FN ålagts uppgiften att tillhandahålla formerna för det globala styret. Denna uppgift har varit och är alltjämt svår att utföra. Som ett uttryck för arvet från västerländsk imperialistisk underordning av andra kom den internationella rätten att få – och har alltjämt – en inneboende slagsida: den har ingen makt att tvinga de undertecknade parterna att infoga sig, i synnerhet inte när ett beslut eller en handling kan stå i konflikt med intressena hos dem som besitter den politiska och militära makten. I en teknologiskt, ekonomiskt och politiskt sammankopplad värld förefaller världsomfattande institutioner likväl nödvändiga för att få till stånd trans- och internationella fördrag, samarbeten och solidaritet mellan territorier som ännu har sina egna lagmässiga gränser. I det sammanhanget är det värdefullt att återvända till en brevväxling mellan Hannah Arendt och Karl Jaspers.20 Med hänvisning till rättegångarna mot de nazistiska företrädarna skrev Arendt:

Det förefaller mig som om nazismens brott spränger lagens gränser; och det är i just detta som deras monstruositet består. För dessa brott är inget straff hårt nog. Det kan mycket väl vara nödvändigt [essential] att hänga Göring, men det är samtidigt helt inadekvat. Alltså, skulden, till skillnad från den kriminella skulden, går utöver och krossar varje slags juridiskt system... Och lika inhuman som deras skuld är, lika oskyldiga är deras offer. Mänskliga varelser kan helt enkelt inte vara lika oskyldiga som alla de var som stod framför gaskamrarna (den mest motbjudande generalen var lika oskyldig som det nyfödda barnet eftersom inget brott förtjänar ett sådant straff). Vi är helt enkelt illa skickade att på en mänsklig eller politisk nivå hantera en skuld bortom brottet och en oskuld bortom godhet och dygd. Sådan är den avgrund som öppnade sig för oss så tidigt som 1933 (faktiskt mycket tidigare, med inledningen av den imperialistiska politiken) och ner i vilken vi har trillat.21

Det godtyckliga tillskrivandet av exempelvis politisk, rasmässig och könad annanhet som diskursiva förelöpare (som alltför ofta blir till biofysiska diton) till folkmord är en avhumaniserande mekanism som bereder väg för handlingar som i efterhand ofta beskrivs som ”onda”. Mer specifikt använder Arendt termen ”radikal ondska” för sådant som:

har att göra med följande fenomen: att göra mänskliga varelser överflödiga som mänskliga varelser (inte att använda dem som ett medel för att nå ett mål, vilket lämnar deras mänskliga väsen därhän och bara inverkar på deras mänskliga värdighet; utan snarare att göra dem överflödiga som varande människor). Detta inträffar så snart all oförutsägbarhet – vilket för mänskliga varelser är detsamma som spontanitet – är utrotad.22

En sådan inramning förstärker den andres status som en fiende som snart förvandlas till en projektionsyta för rädsla och hat; detta är vad som frammanar en masspsykos under vilken saker och ting blir fysiskt påtagliga. Straffålägganden, bortföranden av handikappade, återvandring (nyligen populariserad av extremhögern) i termer av ”skadedjursbekämpning” [deratization] – pestskydd, att bokstavligen göra sig av med (mänskliga) råttor – blir gångbara skydds- och säkerhetsåtgärder.

I sitt svar till Arendt angående frågan om skuld anmärkte Jaspers:

Jag är inte helt bekväm med ditt synsätt eftersom en skuld som går utöver all kriminell skuld ofrånkomligen har ett visst mått av ”storhet” över sig – satanisk storhet – något som för mig passar nazisterna lika illa som allt prat om Hitlers ”demoniska” sidor och så vidare. Det förefaller mig som om vi i allt detta måste urskilja sakernas totala banalitet, deras prosaiska trivialitet, eftersom det är vad som verkligen utmärker dem.23

Och eftersom ”vi” är illa skickade att hantera handlingar ”bortom brott och oskuld”, ”bortom godhet eller dygd” – handlingar som underminerar laglydigheten som grund för att hindra eller sanktionera brott mot mänskligheten – bör det vara uppenbart för oss alla att det inte bara är nödvändigt att utforma ett planetärt system för att hantera sådana ”radikalt onda” handlingar, utan också för att identifiera och förekomma att konflikter eskalerar innan de överträder människans och lagens gränser.

I ett bredare samtida perspektiv kan den av Arendt beskrivna andrafierande logik som ställer gott mot ont – där ”deras” absoluta skuld (mot ”vår” absoluta godhet) är det som driver oss/drivkraften för att kämpa för ”vår” mot slutliga seger och ”deras” nederlag – också bidra till förståelsen av hur, och till vems fördel, det internationella systemet just nu avvecklas. Ageranden som bryter mot internationella avtal och organisationer legitimeras ofta av en nynationalistisk affektiv logik som sätter mitt-land-först och som endast undertrycks av den på makt grundade och i övrigt godtyckliga icke/tvingande ”lagen”. Detta kan också förklara varför vissa aktörer dröjer sig kvar och åtnjuter straffimmunitet. När exempelvis USA konstruerade en nu övergiven flytande hamn längs Gazas strand, kringgick man på ett effektivt sätt de internationella humanitära institutionerna, och hjälpte samtidigt Israel att tillsvidare/på obestämd tid förhindra att nödhjälp nådde Gaza landvägen. Sådana unilaterala åtgärder, som styrs genom halvtransparenta processer utom räckvidd för de internationella institutionerna, undergräver såväl de internationella försöken till konfliktlösning som institutionerna själva. Rutinmässigt legitimerar och normaliserar de även utvinningen från och privatiseringen av konfliktzoner och säkrar landområden där (nationellt favoriserade) företag kan verka utan att knappt underordnas något som helst socialt eller politiskt ansvarsutkrävande.

Under sådana omständigheter är frasen aldrig mer inte bara en opportun politisk lögn eller ett genomgripande drag hos den politiska performativiteten, utan också ett felat ideal. När frasen trots sin implicit partiska eller uteslutande natur framställs som ett allmänmänskligt värde anspelar den på en bättre framtid samtidigt som den systematiskt misslyckas med att ta i beräkning de mekanismer som driver på grymheterna, som exempelvis de tekniker för avskiljande och dödande som kulminerade i men inte slutade med Förintelsen.

I ljuset av det pågående folkmordet i Gaza visar sig frasen aldrig mer vara ett ytterst brutet löfte om en bättre värld.

Alltid redan igen

Efter att socialismen kollapsat utraderade den ”segrande” liberala kapitalismen varje politiskt-ideologiskt alternativ och försökte få människor att glömma Alliansfria rörelsen genom att förlöjliga dess politiska och ekonomiska alternativ till det socialistiska östs och det kapitalistiska västs bipolära system. Som sådant gav den också avgörande bidrag och stöd till den dekoloniala och anti-imperialistiska rörelsen världen över i autonomins och självbestämmandets namn24 Som redan nämnts, var en av rörelsens grundprinciper idén om en fredlig samexistens mellan dess medlemmar, en princip grundad på medvetenheten om att även om en värld utan konflikter är omöjlig är det möjligt att använda andra metoder än våld och krig för att lösa konflikter. Men ”efter Alliansfria rörelsen” och ”efter socialismen” har världen bestämt skakat av sig laglydighetens bojor och med dem även de futurofila skyldigheterna i den fullständiga betydelsen av frasen aldrig mer – det vill säga åtagandet att arbeta för en fredlig och rättvis framtid för alla. I dess ställe har ett utrymme öppnats för en hänsynslös fortsättning på och acceleration av de nekropolitiska och koloniala tillvägagångssätt som nu, återigen, blir uppenbara i decimeringen av palestinska liv, områden och livsvärldar – just som en möjlighet förelåg att helt och fullt (och åter) engagera sig för aldrig mer har den gått förlorad igen.

Vill man istället begripa de omfattande konsekvenserna av det liberala avvisandet av frasen är det nödvändigt att betänka de längre sociopolitiska, historiska, tekniska och ekonomiska processer som formar verkligheten liksom de fenomen som föregick den: å ena sidan de vidare effekterna och affekterna hos kapitalismens och industrialismens processer, vilka omdefinierar det mänskliga förhållandet mellan tid och plats och frikopplar oss från en natur som förvisas till en uppsättning resurser redo att utnyttjas; å andra sidan effekter av en liberalism som med en historisk konsekvens bytt politisk makt mot ekonomisk makt och lämpat över den förra på konservativa, proto-fascistiska och fascistiska aktörer.25

Dessa processer är inneboende i modernitetens vetenskapliga upptäckter och teknologiska framsteg, särskilt så i 1800-talets industriella revolution, och utmärks av vad den tyske sociologen Hermut Rosa kallar för en ”social acceleration”,26 vilken lämnade ett betydande avtryck på den framtida utvecklingen inom vetenskap och teknologi, på våra materiella och symboliska landskap, liksom på det sätt på vilket politiken har kommit att urholkas. Som Rosa påpekar har den sociala accelerationsmen alltså på djupet inverkat på villkoren för våra moderna industriella mänskliga relationer till andra och till världen:

Modernitetens sociokulturella formering visar sig alltså på ett sätt vara dubbelkalibrerad i syfte att göra världen kontrollerbar. Vi är strukturellt tvingade (utifrån) och kulturellt drivna (inifrån) att vrida världen till aggressionens punkt. Den framstår för oss som något som kan inläras, utsugas, omfattas, approprieras, behärskas och kontrolleras. Och ofta handlar detta inte bara om att föra dessa ting – världens segment – inom räckhåll, utan om att göra dem snabbare, enklare, billigare, mer effektiva, mindre motståndskraftiga, mer pålitliga och kontrollerbara.27

Besattheten vid att kontrollera världen har drivit den moderna industriella människan till ett ständigt mer aggressivt förhållande till naturen som legitimerar och normaliserar såväl begäret efter som de verkställande formerna för erövrandet:

Allt som framträder inför oss ska kontrolleras, bemästras, erövras och göras användbart. Abstrakt formulerat låter detta först banalt – men det är det inte. Bakom idén lurar en skrämmande omorganisering av vårt förhållande till världen som sträcker sig långt tillbaka i historien, kulturen, ekonomin och institutionerna men som på nytt har radikaliserats i det tjugoförsta århundradet, inte minst som ett resultat av de teknologiska möjligheter som släppts lösa av digitaliseringen och av kraven på optimering och tillväxt som skapats av den finansiella marknadskapitalismen och en obehindrad konkurrens.28

Inom ramen för den nyliberala erövringen av våra tankar och kroppar, av land och av tid – eller snarare deras ompositionering som resurser, som ett heideggerianskt Bestand – får detta som konsekvens att allt och alla blir en ”radikal fiende”. I motsats till Alliansfria rörelsen placerar en sådan ideologisk och materiell optik segern, herraväldet (eller den finansiella vinsten, för den delen) och förstörelsen som högsta mål och värde – något som inte bara tillämpas på fördrag och lagar, utan också på ”miljön” (det vill säga på planeten i bemärkelsen en uppsättning naturresurser). I slutändan kan allt liv, i dess oförutsägbarhet och spontanitet, bli föremål för en sådan regels utplånande.

En värld som närmas utifrån mottot ”rör dig snabbt och krossa saker”29 har ingen som helst användning för vare sig frasen ”aldrig mer” eller för någon fredlig samvaro; inget utrymme för tänkande, för att lyssna, höra och begrunda; inget behov av att reflektera och diskutera, ingen användning för empati, solidaritet och omsorg. Däremot finns det gott om spelrum för krig och förstörelse. Enligt Darko Suvin är krig ”mer än en metafor för borgerliga mänskliga förhållanden, det är deras allegoriska väsen”;30 eller som Jean Jurés noterat ”le capitaslisme porte la guerre comme la nuée porte l’orage”;31 eller med Rosa Luxemburgs slutsats: ”våld [Gewalt] är kapitalets enda lösning: kapitalackumulationen accepterar våldet som ett permanent vapen, inte bara i dess begynnelse, utan också idag”.32 ”En fortsatt krigsföring under kapitalismen kan aldrig stoppas”, tilläger Suvin, och insisterar sedan på att varje diskussion om modern krigsföring måste förstås i klassmässiga termer: ”sablar, kulor och bombardemang har alltid varit överklassens slutgiltiga svar – först de feodala jordägarna, sedan de centraliserade statliga arméerna – på varje rättvisesökande uppror”.33 Det är alltså en klen tröst att våld, enligt Isaac Asimov, är de inkompetentas sista utpost”.34

En sådan dynamik bryter både samtidens och framtidens utsikter för en fredlig samvaro. Den avtäcker villkoren som drev fram dödandets industrialisering och, vilket är lika avgörande, pekar mot villkoren för en nyliberal totalitarism. Den senare – som eskalerar en krigisk teknopolitik vilken aktivt förhindrar och försvagar fredliga lösningar på dispyter till förmån för profiten från att beväpna en eller fler parter – omhuldar frasen aldrig mer i sitt tal samtidigt som den cyniskt sätter den ur spel genom att oavlåtligen framhålla våld och krig som ”humanitära” medel för konfliktlösning samt stävja eller tysta kritik.

Om man likväl skulle vilja kämpa emot det Denkverbot som verkar uppstå ur denna situation,35 mot det cyniska införandet av och neutraliseringen av radikalt uteslutande och mytologiska förhållanden mellan gott och ont, vi och dem, mot underordning och förstörelse, mot legitimeringen av krig som en acceptabel lösning är man – det vill säga ”vi” – nödgad att ta sig an en substantiell begreppslig liksom faktisk omkonfigurering av ”våra” villkor och former för mänsklig, icke-mänsklig och miljömässig samhörighet, ”vår” katastrofala övervärdering av finansiell ”hållbarhet” och ”vinst”.

I dagens läge måste varje svar på frågan om den framtida relevansen för frasen aldrig mer undvika binära svar som ”ja eller nej”, ”vi eller dem”, ”seger eller nederlag”. Och då inte bara för att mantrat så här långt uteslutande har gällt västvärlden, utan för att själva villkoren och utsikterna för livet i posthärvan av post-upplysning, teknofeodalism, nyliberalism och extraktivism grundas på aggression och våld. I linje med Rosa kan aggression förstås som en strukturell, politisk, ekonomisk och affektiv handlingsform: för att göras kontrollerbara är vi alltmer avdelade, polariserade, desorienterade, bedövade subjekt med en uppenbart ständigt försvagad politisk och kulturell förmåga att bemöta vad som framstår som oöverstigliga eko-politiska kriser. Likväl bör vi i själva verket söka forma radikalt annorlunda strukturer och utöva en radikalt annorlunda politik som låter solidaritet, jämlikhet, omsorg, vänlighet och mildhet lägga grunden för ett beslutsamt socio-ekologiskt handlande.

För att så ska ske måste uppmärksamheten riktas mot kraften i mildhet, vilken med Anne Dufourmantelle ord är ”en aktiv passivitet som kan bli en utomordentlig kraft för ett symboliskt motstånd och som sådant avgörande för både etik och politik”.36 Men idag är ”mildhet något som oroar. Vi begär den, men den är inte godtagbar. Om de milda inte föraktas blir de antingen förföljda eller helgonförklarade. Vi överger dem eftersom mildheten som kraft visar oss vår egen faktiska svaghet.”37 Samma sak skulle kunna sägas om dem som strävar efter fred som alltid har framställts som ynkryggar eller förrädare.38

Avslutningsvis, frågan om huruvida den innevarande extraktivistiska nyliberala världsordningen är förmögen att härbärgera ett sammanhållet, föränderligt och historiskt informerat samtal om en fredlig samvaro och frasen aldrig mer uppvisar ett dubbelt hinder: för det första föder det uppenbara begäret efter att förstå världen som fientlig (i linje med Rosa ovan) våld och aggressioner i allmänhet; och för det andra, men inte mindre viktigt, blir det förflutnas trauman alltmer avlägsna och framtida generationer alltmer oemottagliga för våldsamma bilder och historier från förr.

För många människor idag har aldrig mer-kriget för nästan hundra år sedan, dess deportationer, massmord och förstörelse begränsad känslomässig efterklang. I ljuset av detta frågar sig Suvin hur ”vi kan utforma det nya sensorium som mänskligheten behöver för sin fortsatta existens”.39 För som Hans Kellner understryker – trots att revisionismen som term och begrepp idag är befläckad av Förintelseförnekare40 – är det:

utmärkande för en aktiv historiekultur att revidera. Varje nytt bidrag till diskursen [...] kräver sin egen identitet när den fram håller de egenskaper som omformar och utmanar materialets betydelse. [---] För att bringas till liv, eller åtminstone det sken av liv som möjliggör akademiska och till och med folkliga publika tioner, måste materialet omformas och detta innebär följaktligen revision. Alternativet är ritualen, som till och med den öppnar sig för samtidens krav.41

Det sätt på vilket historisk kunskap produceras, reproduceras, sprids och populariseras, och detta inte enbart genom utbildning utan också genom populärkultur och medier, måste ständigt uppfinnas på nytt, kalibreras och uppdateras på ett sådant sätt att ”det förgångna” förmår ”tala på nytt” till kommande generationer. På så vis kan det påverka dem – i bemärkelsen beröra dem och få dem att röra – på nya sätt,42 liksom förhindra den minneshistoriska negationism och amnesi som livnär (sig på) politiska lögner.43

Översättning från engelskan: Johannes Björk

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–VCRC

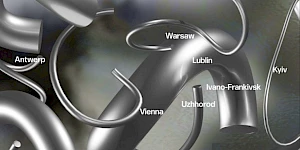

Kyiv Biennial 2023

L’Internationale Confederation is a proud partner of this year’s edition of Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Where are the Oases?

PEI OBERT seminar

with Kader Attia, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Emily Jacir, Achille Mbembe, Sarah Nuttall and Françoise VergèsAn oasis is the potential for life in an adverse environment.

-

MACBA

Anti-imperialism in the 20th century and anti-imperialism today: similarities and differences

PEI OBERT seminar

Lecture by Ramón GrosfoguelIn 1956, countries that were fighting colonialism by freeing themselves from both capitalism and communism dreamed of a third path, one that did not align with or bend to the politics dictated by Washington or Moscow. They held their first conference in Bandung, Indonesia.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

Maria Lugones Decolonial Summer School

Recalling Earth: Decoloniality and Demodernity

Course Directors: Prof. Walter Mignolo & Dr. Rolando VázquezRecalling Earth and learning worlds and worlds-making will be the topic of chapter 14th of the María Lugones Summer School that will take place at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven.

-

–tranzit.ro

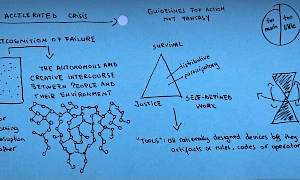

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Archive of the Conceptual Art of Odesa in the 1980s

The research project turns to the beginning of 1980s, when conceptual art circle emerged in Odesa, Ukraine. Artists worked independently and in collaborations creating the first examples of performances, paradoxical objects and drawings.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school is organised by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in partnership with ZRC SAZU (the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts) as part of the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–MACBA

Song for Many Movements: Scenes of Collective Creation

An ephemeral experiment in which the ground floor of MACBA becomes a stage for encounters, conversations and shared listening.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–

Kyiv Biennial 2025

L’Internationale Confederation is proud to co-organise this years’ edition of the Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica

Curated by MACBA director Elvira Dyangani Ose, along with Antawan Byrd, Adom Getachew and Matthew S. Witkovsky, Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica is the first major international exhibition to examine the cultural manifestations of Pan-Africanism from the 1920s to the present.

-

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

–

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Study Group: Aesthetics of Peace and Desertion Tactics

In a present marked by rearmament, war, genocide, and the collapse of the social contract, this study group aims to equip itself with tools to, on one hand, map genealogies and aesthetics of peace – within and beyond the Spanish context – and, on the other, analyze strategies of pacification that have served to neutralize the critical power of peace struggles.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Near East, Far West. Kyiv Biennial 2025

The main exhibition of the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, titled Near East, Far West, is organized by a consortium of curators from L’Internationale. It features seven new artists’ commissions, alongside works from the collections of member institutions of L’Internationale and a number of other loans.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: The Brighter Nations in Solidarity: Even in the Midst of a Genocide, a New World Is Being Born

PEI Obert presents a lecture by Vijay Prashad. The Colonial West is in decay, losing its economic grip on the world and its control over our minds. The birth of a new world is neither clear nor easy. This talk envisions that horizon, forged through the solidarity of past and present anticolonial struggles, and heralds its inevitable arrival.

-

–M HKA

Homelands and Hinterlands. Kyiv Biennial 2025

Following the trans-national format of the 2023 edition, the Kyiv Biennial 2025 will again take place in multiple locations across Europe. Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA) presents a stand-alone exhibition that acts also as an extension of the main biennial exhibition held at the newly-opened Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN).

In reckoning with the injustices and atrocities committed by the imperialisms of today, Kyiv Biennial 2025 reflects with historical consciousness on failed solidarities and internationalisms. It does this across an axis that the curators describe as Middle-East-Europe, a term encompassing Central Eastern Europe, the former-Soviet East and the Middle East.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Bodies of Evidence. A lecture by Ido Nahari and Adam Broomberg

In the second day of Open PEI, writer and researcher Ido Nahari and artist, activist and educator Adam Broomberg bring us Bodies of Evidence, a lecture that analyses the circulation and functioning of violent images of past and present genocides. The debate revolves around the new fundamentalist grammar created for this documentation.

-

–

Everything for Everybody. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Everything for Everybody’ takes place in the Ukraine, at the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture.

-

–

In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture’ takes place at the Dovzhenko Centre in Kyiv.

-

MACBA

School of Common Knowledge: Fred Moten

Fred Moten gives the lecture Some Prœposicions (On, To, For, Against, Towards, Around, Above, Below, Before, Beyond): the Work of Art. As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA presents this lecture on artworks and art institutions in relation to the challenge of blackness in the present day.

-

–MACBA

Visions of Panafrica. Film programme

Visions of Panafrica is a film series that builds on the themes explored in the exhibition Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, bringing them to life through the medium of film. A cinema without a geographical centre that reaffirms the cultural and political relevance of Pan-Africanism.

-

MACBA

Farah Saleh. Balfour Reparations (2025–2045)

As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA is co-organising Balfour Reparations (2025–2045), a piece by Palestinian choreographer Farah Saleh included in Hacer Historia(s) VI (Making History(ies) VI), in collaboration with La Poderosa. This performance draws on archives, memories and future imaginaries in order to rethink the British colonial legacy in Palestine, raising questions about reparation, justice and historical responsibility.

-

MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica OPENING EVENT

A conversation between Antawan I. Byrd, Adom Getachew, Matthew S. Witkovsky and Elvira Dyangani Ose. To mark the opening of Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, the curatorial team will delve into the exhibition’s main themes with the aim of exploring some of its most relevant aspects and sharing their research processes with the public.

-

MACBA

Palestine Cinema Days 2025: Al-makhdu’un (1972)

Since 2023, MACBA has been part of an international initiative in solidarity with the Palestine Cinema Days film festival, which cannot be held in Ramallah due to the ongoing genocide in Palestinian territory. During the first days of November, organizations from around the world have agreed to coordinate free screenings of a selection of films from the festival. MACBA will be screening the film Al-makhdu’un (The Dupes) from 1972.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Cinema Commons #1: On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes

On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes is a Museo Reina Sofía film programme overseen by Miriam Martín and Ana Useros, and the first within the project The Cinema and Sound Commons. The activity includes a lecture and two films screened twice in two different sessions: John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948) and John Gianvito’s The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (2001).

-

–

Vertical Horizon. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Vertical Horizon’ takes place at the Lentos Kunstmuseum in Linz, at the initiative of tranzit.at.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

-

MACBA

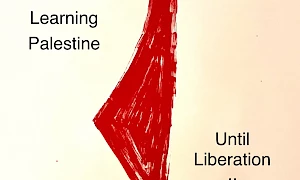

PEI Obert: Until Liberation: A Collective Reading and Listening Session by Learning Palestine

PEI Obert presents a collective session with Learning Palestine. At this historical juncture – amid the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the censorship and repression of all things Palestinian – Learning Palestine invites us to gather not only in refusal but also in affirmation.

Related contributions and publications

-

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

The Kitchen, an Introduction to Subversive Film with Nick Aikens, Reem Shilleh and Mohanad Yaqubi

Nick Aikens, Subversive FilmSonic and Cinema CommonslumbungPast in the PresentVan Abbemuseum -

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

The Veil of Peace

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuPast in the Presenttranzit.ro -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Reading list - Summer School: Our Many Easts

Summer School - Our Many EastsSchoolsPast in the PresentModerna galerija -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Dispatch: ‘I don't believe in revolution, but sometimes I get in the spirit.’

Megan HoetgerSchoolsPast in the Present -

Dispatch: Notes on (de)growth from the fragments of Yugoslavia's former alliances

Ava ZevopSchoolsPast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Present Present Present. On grounding the Mediateca and Sonotera spaces in Malafo, Guinea-Bissau

Filipa CésarSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the Present -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

Some Things We Learnt: Working with Indigenous culture from within non-Indigenous institutions

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteLand Relations -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations