Around the Postcolony and the Museum. Curatorial Practice and Decolonizing Exhibition Histories

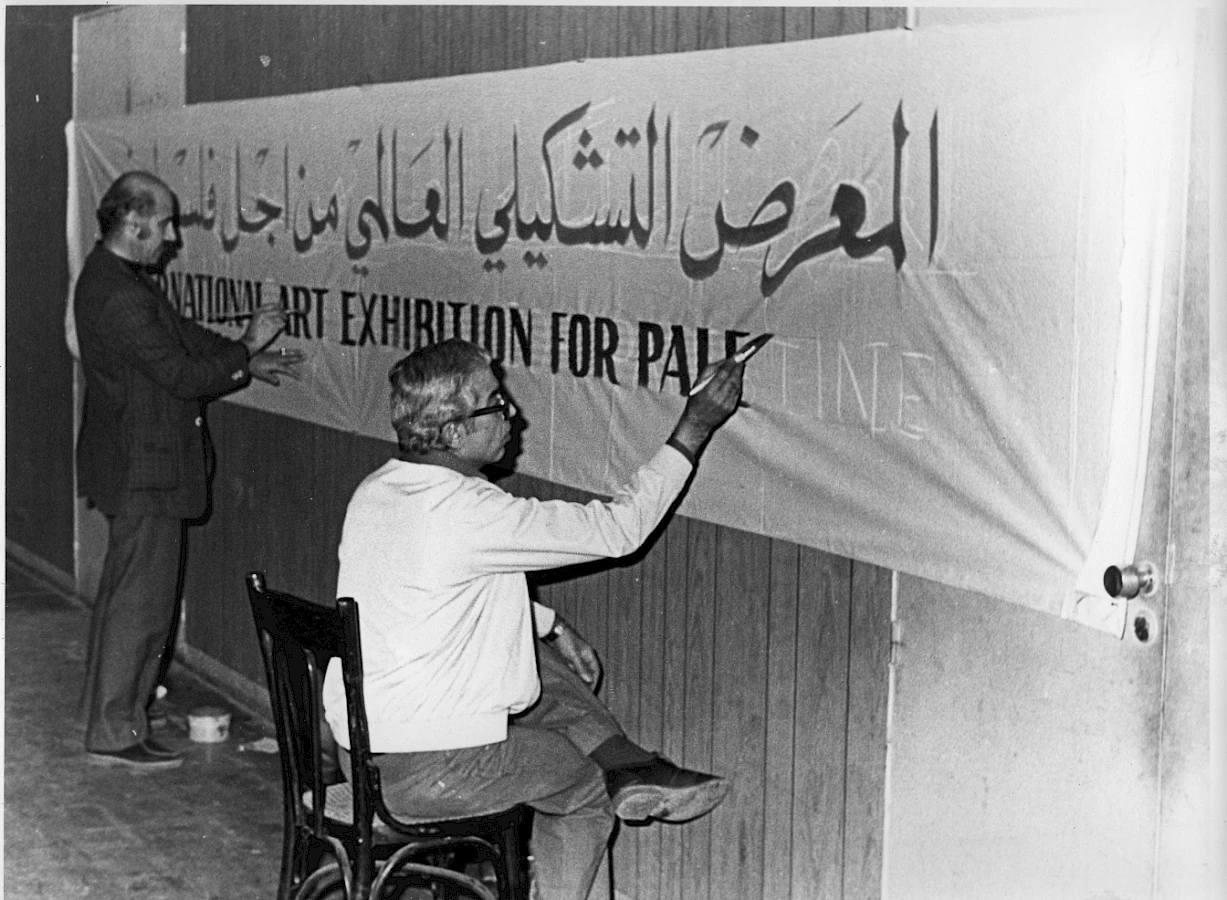

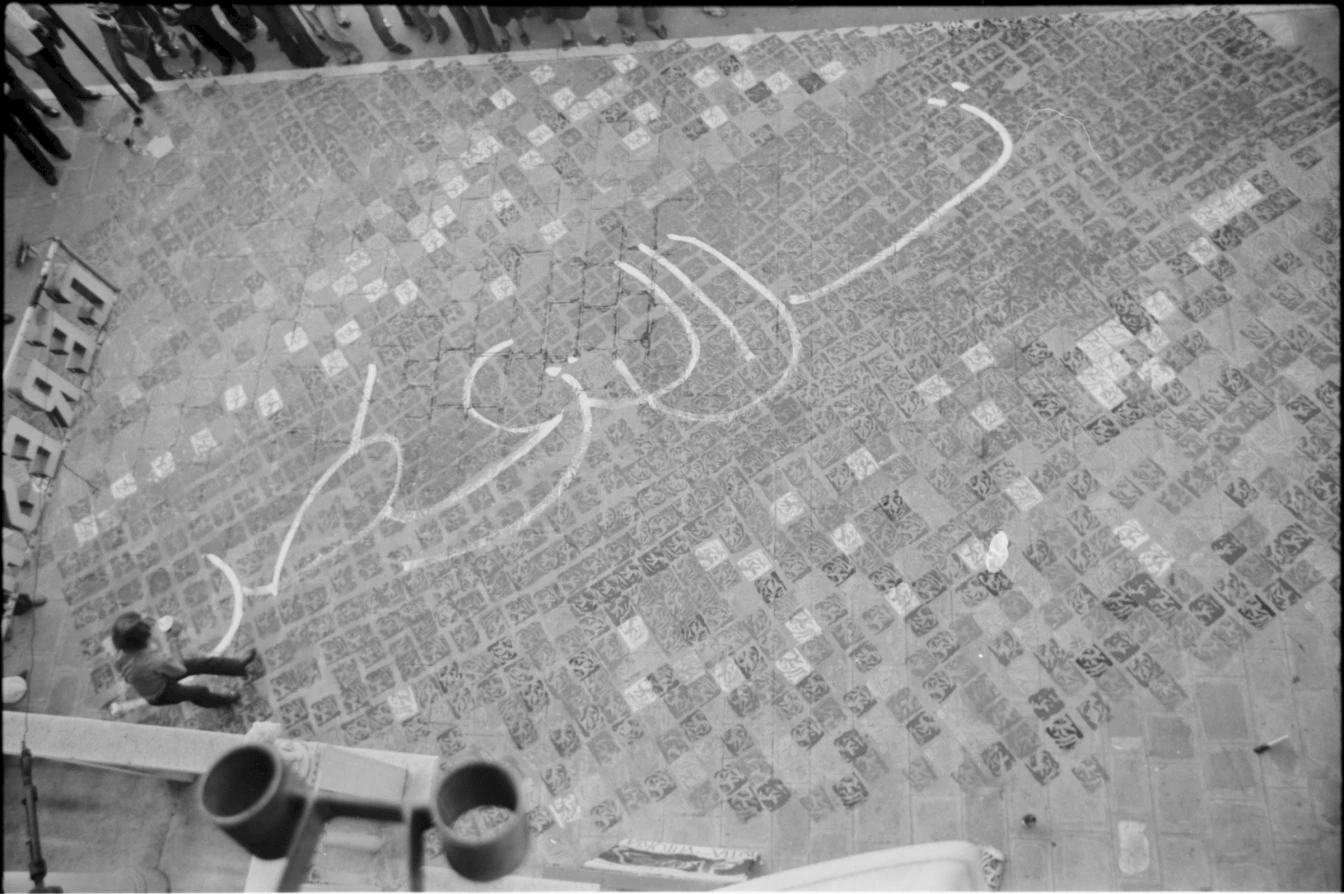

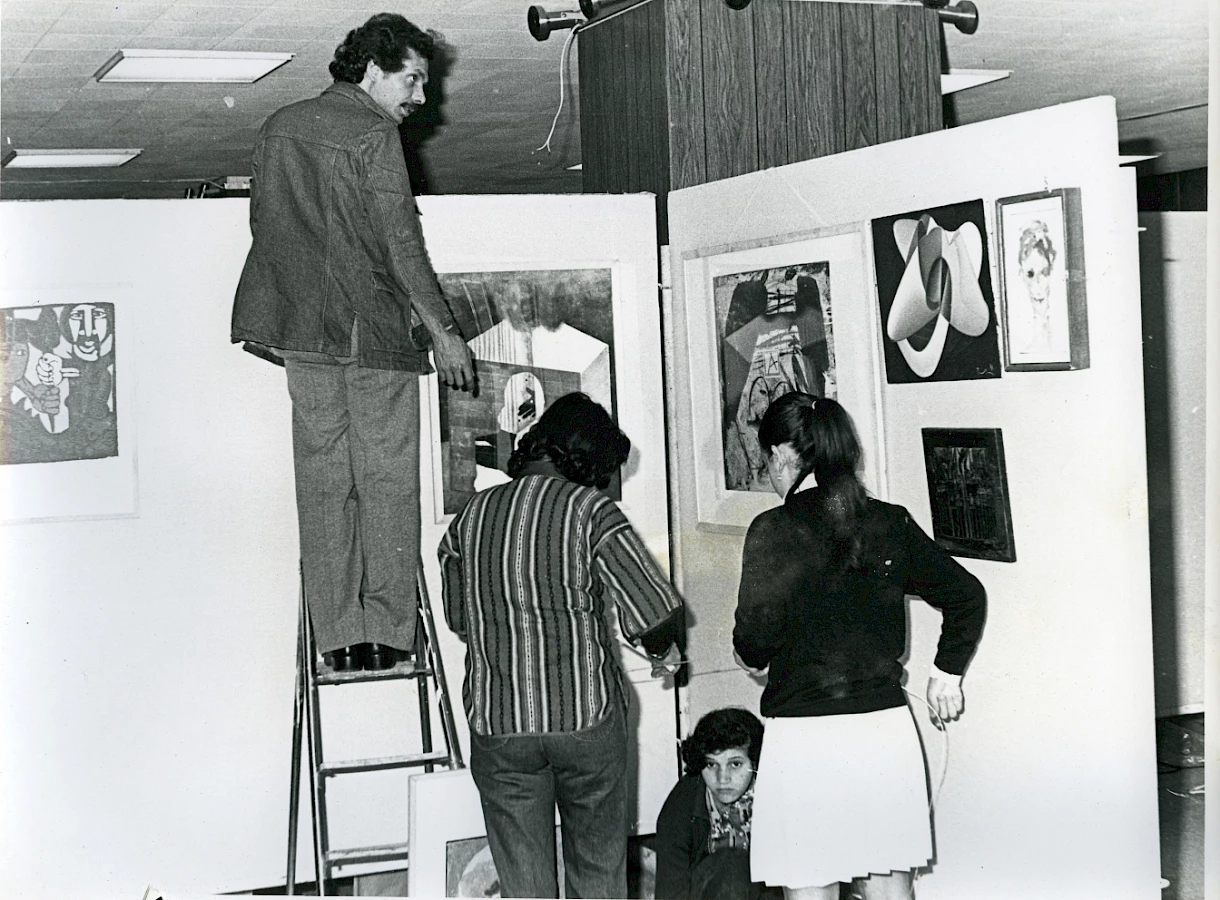

Jamil Shammout (Palestine) and Michel Najjar (Palestine) paint the banner of the exhibition. Courtesy: Claude Lazar.

So it can be said that it [the book, On the Postcolony. Studies on the History of Society and Culture] is concerned with memory only insofar as the latter is a question, first of all, of responsibility towards oneself and towards an inheritance. I'd say that memory is, above all else, a question of responsibility with respect to something of which one is often not the author. Moreover I believe that one only truly becomes a human being to the degree that one is capable of answering to what one is not the direct author of, and to the person with whom one has, seemingly, nothing in common. There is, truly, no memory except in the body of commands and demands that the past not only transmits to us but also requires us to contemplate. I suppose the past obliges us to reply in a responsible manner. So there is no memory except in the assignment of such a responsibility.

–Achille Mbembe, 20061

Earlier this year, Kristine Khouri and I curated an exhibition entitled Past Disquiet: Narratives and Ghosts from The International Art Exhibition for Palestine, 1978 at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MACBA) in Barcelona (20 February – 1 June 2015). It is a documentary and archival exhibition centred on and around the history of the International Art Exhibition for Palestine that was inaugurated in the spring of 1978 at the Beirut Arab University in Lebanon. Organised by the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), it comprised approximately 200 artworks donated from nearly thirty countries. It included work by very well-known artists such as: Joan Miró (Spain), Antoni Tàpies (Spain), Joan Rabascall (Spain), Julio Le Parc (Argentina), Renato Guttuso (Italy), Carlos Cruz-Diez (Venezuela), Roberto Matta (Chile), Aref al-Rayess (Lebanon), Dia al-Azzawi (Iraq), George al-Bahgoury (Egypt), Ziad Dalloul (Syria), Mohamed Melehi (Morocco), Ernest Pignon-Ernest (France), Gérard Fromanger (France), the Collectif Malassis (France).

The International Art Exhibition for Palestine was intended as the seed collection of a museum in exile for Palestine. Until it could be repatriated to a free and just Palestine, it would take the form of an itinerant exhibition touring the world. After Beirut, it travelled to Norway, Japan and Iran from 1979 to 1982. The building where the artworks and the exhibition's archives and documentation were stored was shelled by the Israeli army during the Israeli siege of Beirut in 1982. Everything relating to this exhibition seemed to be lost. But little by little, scattered duplicates and copies were found in the personal archives of those who contributed to its realisation. For five years, Kristine Khouri and I tried to reconstitute the story of the making of this exhibition.

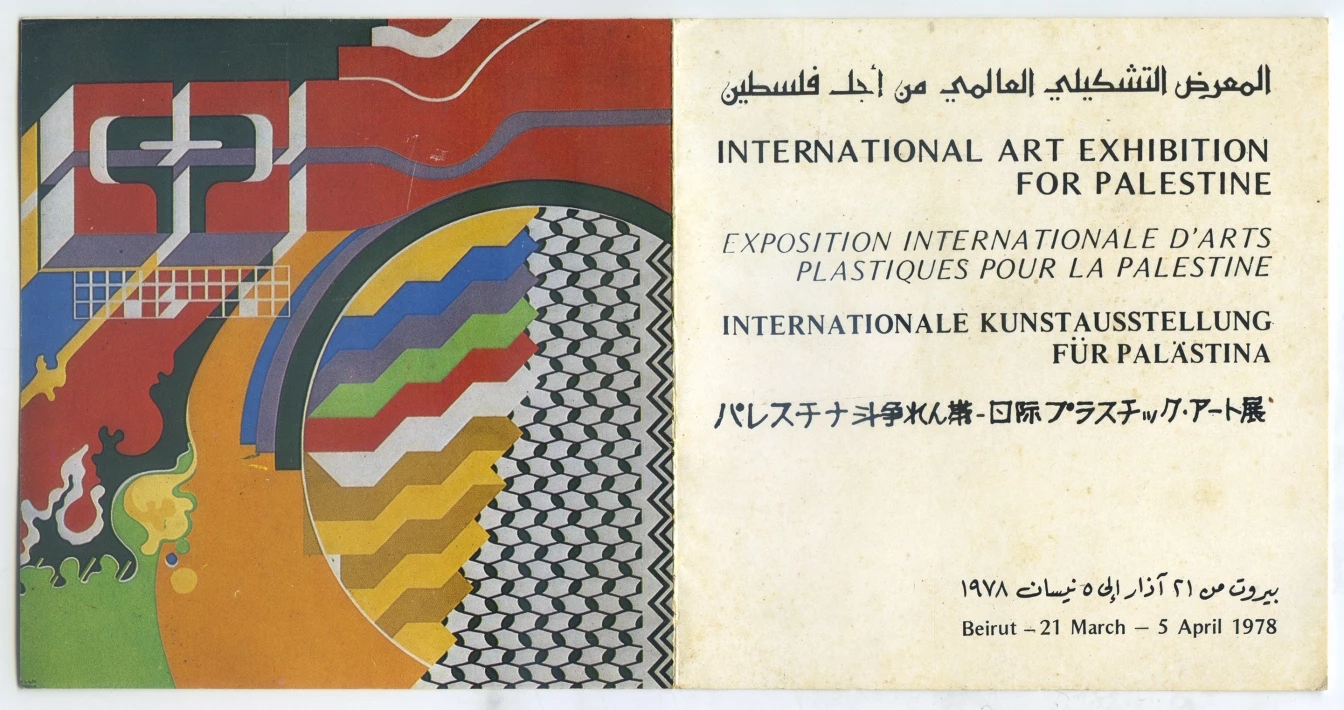

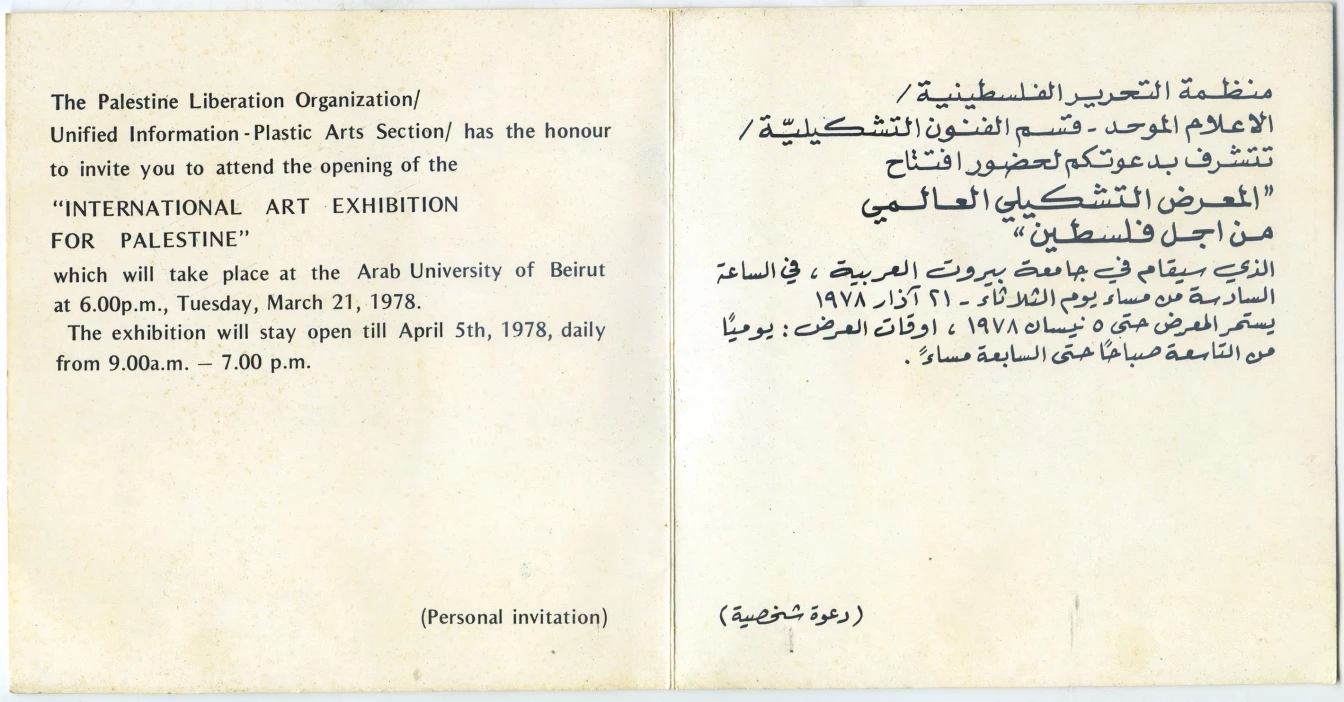

Invitation for the International Art Exhibition for Palestine, Beirut, 1978. Cover artwork by Mohammed Chebaa (Morocco). Courtesy: Mona Saudi.

Invitation for the International Art Exhibition for Palestine, Beirut, 1978. Cover artwork by Mohammed Chebaa (Morocco). Courtesy: Mona Saudi.

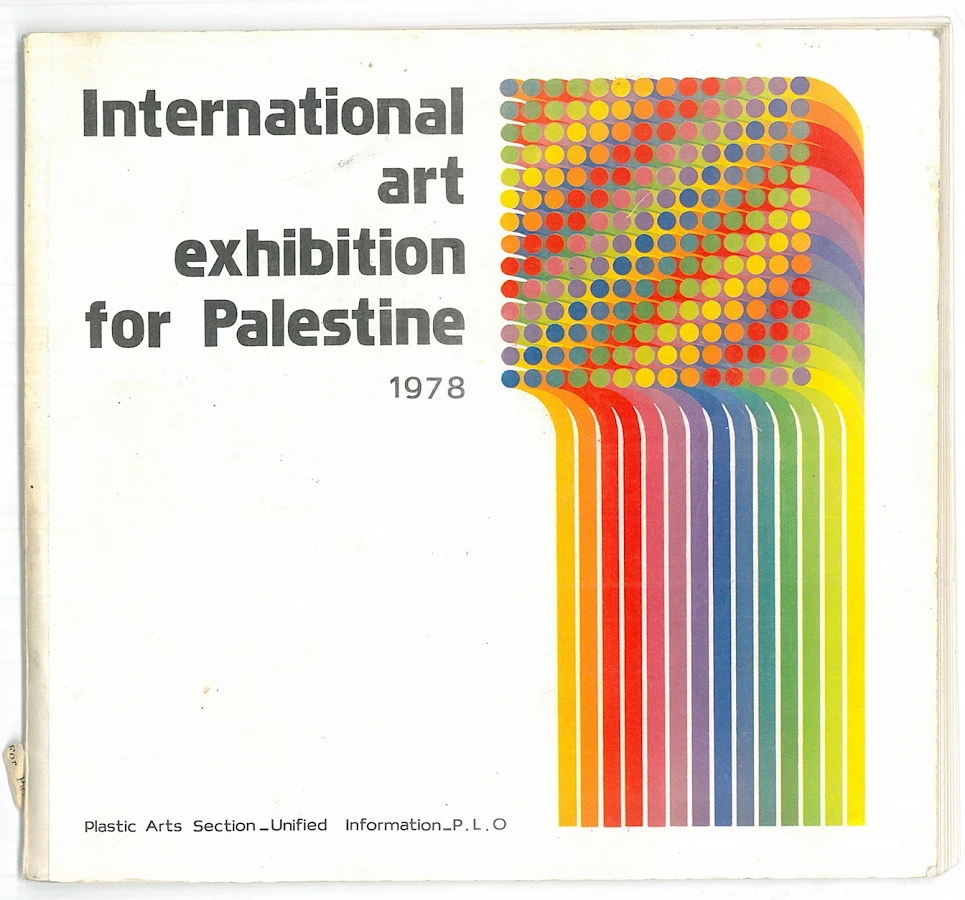

English cover of the catalogue for the International Art Exhibition for Palestine, Beirut, 1978.

It all started by coincidence when we discovered a copy of the catalogue in the reference library of an art gallery in Beirut. Needless to say, we were highly intrigued. The International Art Exhibition for Palestine embodies a unique initiative in the Arab world, in scale and scope. It surpasses all the exhibitions that took place in the region during that period and even a couple of decades after. Astonishingly, it took place amidst Lebanon's Civil War, and opened only a week after a UN-brokered truce was implemented between Israel and Lebanon, and a UN peace-keeping force was deployed in South Lebanon to prevent armed confrontations between the Israeli army and Palestinian factions and their Lebanese allies. Eventually, the exhibition's reconstructed history revealed an unwritten or scarcely documented, shared history of politically-engaged artists and initiatives, that links grassroots artist collectives in Paris, Rome and Tokyo, artist unions in Damascus, Baghdad, and Casablanca, seminal biennials in Venice, Baghdad and Rabat and museums in Santiago de Chile and Cape Town.

We were commissioned by Bartomeu Marí to present our research as a documentary and archival exhibition at the MACBA. Indeed, it intersected with two of the museum's programmatic leitmotivs under his mandate, namely staging exhibition histories are a means to interrogate the historiography of art and production of Eurocentric, or Western-centric canons and foregrounding 'decolonising the museum' is an overarching creed that informed the museum's various departments.

To revisit the conceits that guided our research and curatorial approach, I will draw on Achille Mbembe's notion of 'postcolony'. He does not propose this term to undermine the interpretive framework of postcolonial theory but because it suits his interrogations best:

In many respects my book adopts a different approach from that of most postcolonial thinking, if only over the privileged position accorded by the latter to questions of identity and difference, and over the central role that the theme of resistance plays in it. There is a difference, to my mind, between thinking about the 'postcolony' and 'postcolonial' thought. The question running through my book is this: 'What is 'today', and what are we, today?' What are the lines of fragility, the lines of precariousness, the fissures in contemporary African life? And, possibly, how could what is, be no more, how could it give birth to something else? And so, if you like, it's a way of reflecting on the fractures, on what remains of the promise of life when the enemy is no longer the colonist in a strict sense, but the 'brother'?

When we launched our research, we had no intention of presenting its variegated findings in the format of an exhibition, and certainly not in a museum of contemporary art. We were acutely aware that we were conducting this inquiry as the globalised art market reached the Arab world and Arab artists and was prolific. Museums, institutional and private collectors (local, regional and international) were not only interested in contemporary art, but increasingly in the art of generations that preceded it (vaguely referred to as 'modern' art). In the production of value, the market came before scholarship, or in other words, the market-driven production of value superseded and outpaced expert or scholarly production of knowledge. Consequently, the historical narrative that suited consumption, stitched together from the (whimsical) harvests of auction catalogues, art fair sensation and art dealer merchandising content, came to prevail. Not only is it unimaginable to emulate or reproduce the International Art Exhibition for Palestine today with contemporary artists, but it is also unimaginable that it did actually take place some thirty years ago. As our research progressed, we came to realise that we were bringing a counter-history to the surface. And that became one of our prime motivations, we were impelled to foreground the questions that challenge wide perceptions of modern art in the Arab world.

We recognised in the story of the International Art Exhibition for Palestine that 'fissure', or 'line of precariousness' described by Mbembe. To echo his words, it beckoned the question: "how could what is, be no more, how could it give birth to something else?" As the research and its transformation into the Past Disquiet exhibition revisited a chapter in the history of artistic practice entrenched in the political engagement of the international anti-imperialist solidarity movement of the 1970s, it did not produce a linear and continuous narrative, but rather showcased speculative histories of a turbulent recent past, while overtly engaging with the issues of oral history, the trappings of memory and writing history in the absence of cogent archives. Past Disquiet did not include a single original artwork or display original archival documents. Instead, it reproduced facsimile of yellowed newspaper clippings, magazines and publications – most of which are no longer in circulation – pamphlets from revolutions that have lost their fervour, and photographs from boxes that had not been opened in decades. It exhibited stories culled from memories. The 'raw material' we collected was, to a large extent, a first-person oral history, replete with subjective affect, the trappings of remembering and forgetting, recorded by individuals across countries, cultures and languages (in Egypt, France, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, and Palestine...). In the absence of access to an officially-sanctioned narrative and paper-trail, the information sourced from interviews could not be fact-checked. A number of individuals who played a key role in making the International Art Exhibition for Palestine are deceased.

We struggled to craft the exhibition title because we wanted to acknowledge the research process as much as its outcome. It was minted by Paul Beatriz Preciado who oversaw our project at the museum and was an incredibly generous, sharp and engaged interlocutor. During the intense exchanges between us about the wordsmithing of the title, he proposed Past Disquiet, in Spanish. 'Disquiet' (and the Arabic qaleq) refers to an unsettled recent past – one that lacks closure. In Arabic, instead of the word 'past', we use dhikr, precisely because of its ambiguity that implies both remembering and resurrecting from death, or forgetting. We translated it liberally rather than literally, and in retrospect, I find the Arabic title to be the closest representation of what the exhibition incarnates, because dhikr is active in contrast with 'past'. We were very conscious of our responsibility. The introductory wall text read partly as follows:

"Research that involves recording personal recollections and using private archives implies a high degree of responsibility because people have entrusted us with fragments of their own lives, their subjective account of lived experiences of which they might not otherwise have produced a public record. Our research has yielded an eclectic repository of stories and anecdotes, as well as digital copies of documents, images and film footage. Our methodology was closer to detective work, replete with entirely unexpected fortuitous coincidences, even encounters with ghosts, allegorical and otherwise. As we were transforming our findings into the exhibition, we used our own voices to retell some of the anecdotes, and so underline that we are proposing a subjective and speculative history, or histories, about events that have either not yet been written into the history of art per se or have been forgotten entirely."

This sense of responsibility led us to use our own voices in order to piece together the many versions of intersecting histories, to transgress the binary of 'objective' and 'subjective', but also to move past the morbid grip of lingering vicissitudes, unresolved enmities that mire narratives of that period and undermine the ground of prevailing narratives today. In other words, we wanted to activate a memory as well as interrogations that might contribute significantly to the discourse and practices of subversion in the present, in Beirut, the Arab world, but also Paris, Rome, Tokyo and Cape Town. The research surfaced a cartography of artist and exhibition practices across the world, within the realm of the international, anti-imperialist, radical leftist solidarity, connected through a network of politically-engaged artists and militants who mobilised their creative energies around the defence of various causes. From the outset, our inquiry was closer to detective work than to conventional scholarly research, and we travelled to several countries to interview artists and other personalities, but even at that scale, the geo-cultural paradigms that regiment our contemporary perception of art history were irrelevant. In France, we interviewed Brazilian, Argentinian, Palestinian and Syrian artists as well as French artists, who were involved in the museum in exile in solidarity with Salvador Allende, or the Jeune Peinture,or the Jeune Peinture, or Art Against Apartheid, as well as in the International Art Exhibition for Palestine.

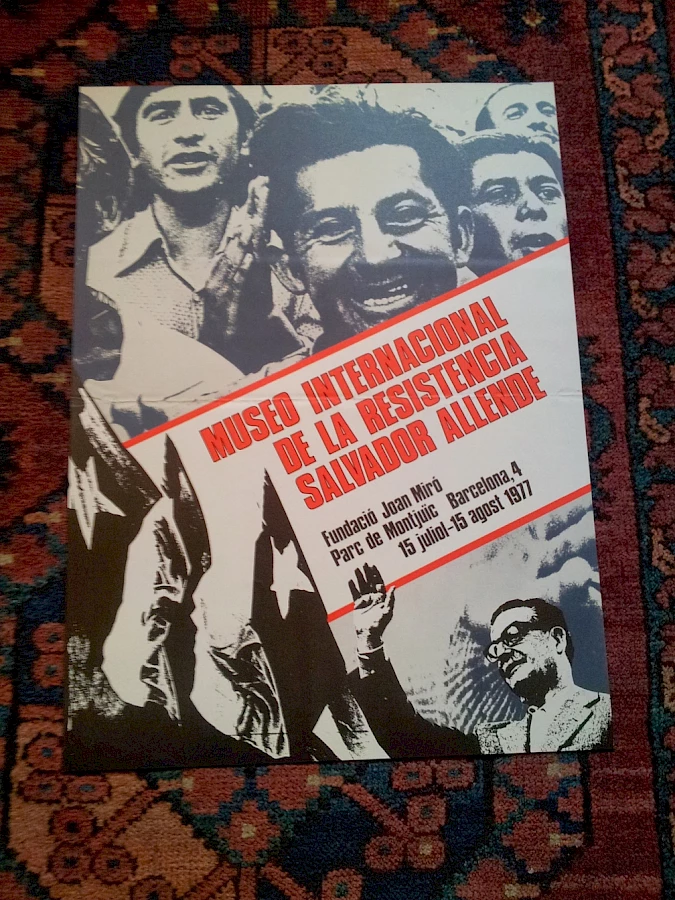

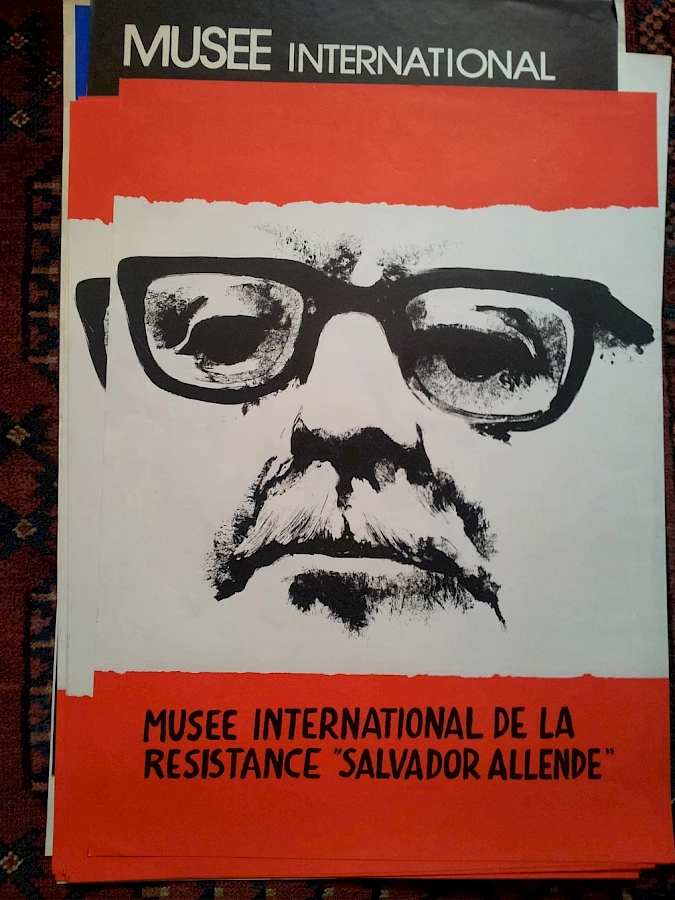

Posters for itinerant exhibition of the International Resistance Museum for Salvador Allende. France, date unknown. Courtesy: Jacques Leenhardt.

Posters for itinerant exhibition of the International Resistance Museum for Salvador Allende. France, date unknown. Courtesy: Jacques Leenhardt.

The MACBA was the first epistemic space where Past Disquiet was made manifest, and we are eager to present the exhibition elsewhere around the world. Some cities, like Paris, Beirut, Tokyo and Ramallah would have a particular resonance because of their place in the 'original story'. In many ways, Past Disquiet is a prism from which we can refract, or foreground, questions about a recent, yet blotted out and thus complicated, past responsibly. In fact, in our private short-hand, we refer to the MACBA exhibition as "version 1.0". At present, we are thinking through forthcoming iterations that will address questions that we did not have the space, or resources, to address in the first version. For instance, the question of the artistic languages or genres, schools or styles included in the exhibition is an important one. A visitor to the exhibition staged in Beirut in 1978 saw paintings, lithographs, etchings, drawings and sculptures in almost all styles, or genres: primitive or naïve, abstract art, figurative, optical art, neo-realism, social realism, critical figuration... At that time, the radical left in Italy and France regarded abstraction as bourgeois art, while the subversive, counter-cultural vanguard in Morocco defended abstraction because the post-colonial elite deemed naïve and landscape painting as the only 'authentically' Moroccan art. None of the artists from the Soviet Union or former East were anti-conformist, rather, they were for the most part 'official artists'. In other words, the International Art Exhibition for Palestine is an incarnation of the coexistence of the multiplicity or plurality of modern art in the 1970s. What do we make of this 'Babel' of art languages and styles? What was the marrow welding the solidarity networks across the so-called North and so-called South? What did these instances of international solidarities translate to for the artists' subjectivities? Certainly the brotherhood between French artists on the left (in its myriad manifestations) and artists seeking political asylum created a solidarity that gave 'refugees' asylum. Today that is unimaginable in the art circles of Paris or Rome.

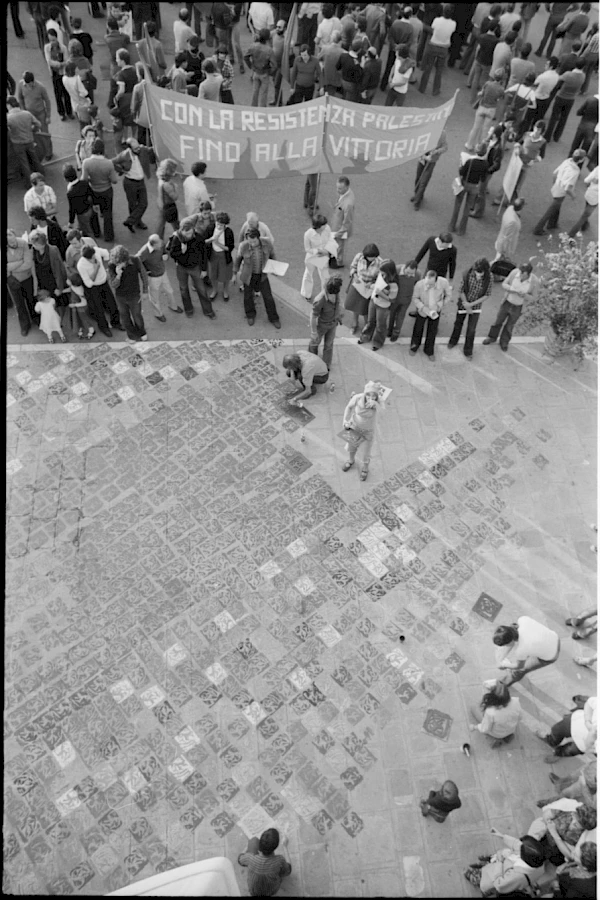

Photographic documentation of the public action that took place in Mestre during the Venice Biennial in solidarity with Palestinian refugees in Tel al-Zaatar, the refugee camp under siege in Beirut, 1976. Courtesy: Sergio Traquandi.

Photographic documentation of the public action that took place in Mestre during the Venice Biennial in solidarity with Palestinian refugees in Tel al-Zaatar, the refugee camp under siege in Beirut, 1976. Courtesy: Sergio Traquandi.

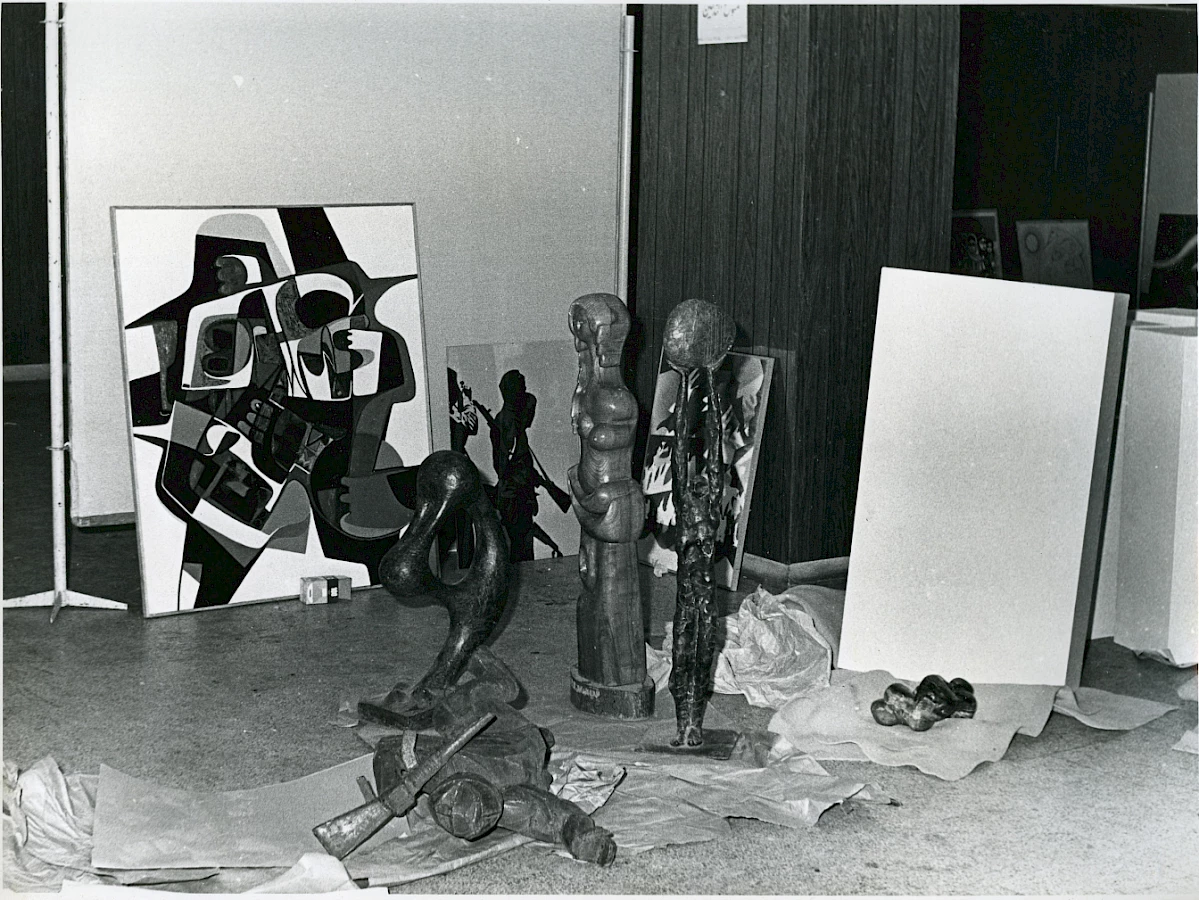

Exhibition installation. Courtesy: Claude Lazar.

Exhibition installation. Courtesy: Claude Lazar.

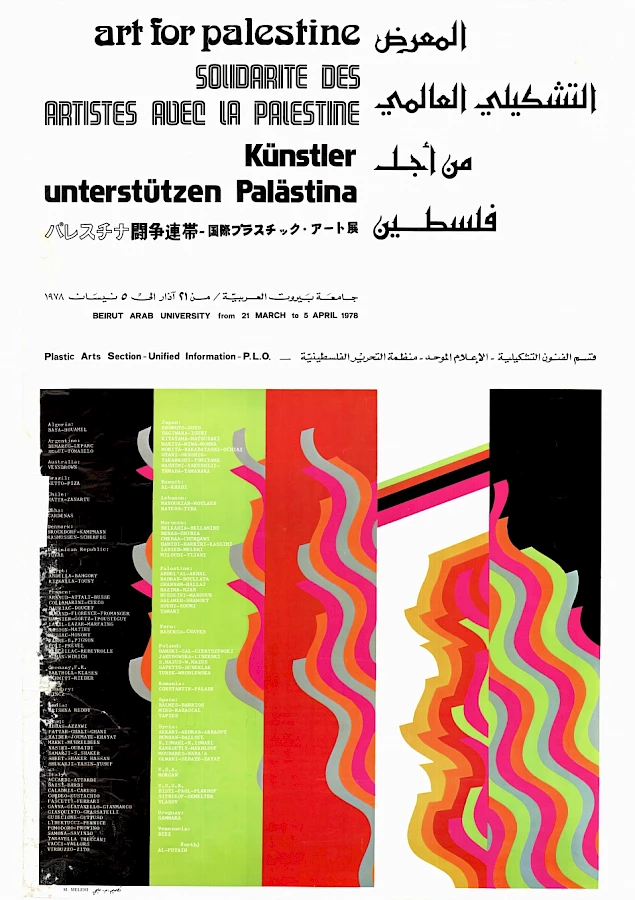

Poster for the International Art Exhibition for Palestine, Beirut, 1978. Designed by Mohammed Melehi (Morocco). Courtesy: Samir Salameh.

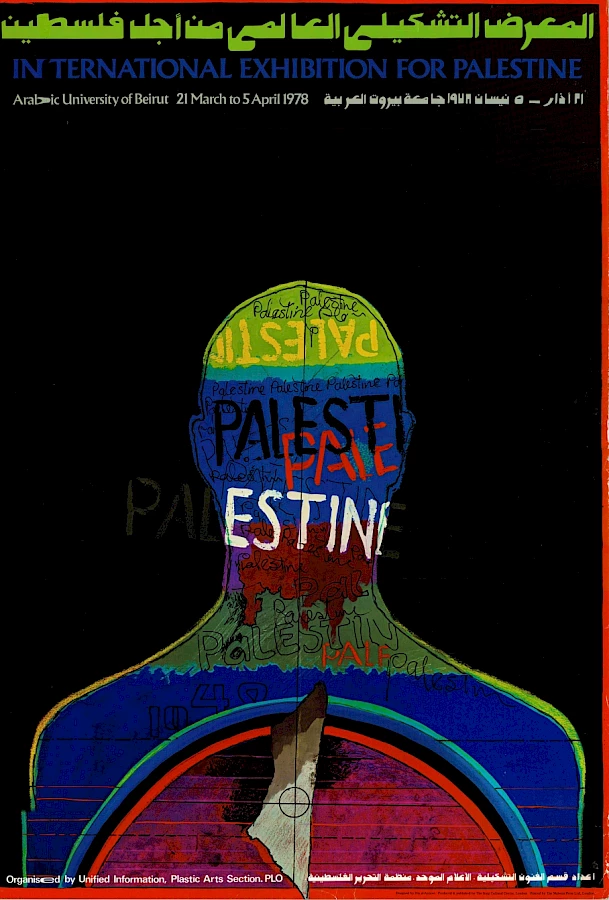

Poster for the International Art Exhibition for Palestine, Beirut, 1978. Designed by Dia al-Azzawi (Iraq). Courtesy: Samir Salameh.

I see the International Art Exhibition for Palestine as an eloquent crystallisation of a postcolonial occurrence. As Achille Mbembe explains:

In showing how the colonial and imperial experience has been codified in representations, divisions between disciplines, their methodologies and their objects, it invites us to undertake an alternative reading of our common modernity. It calls upon Europe to live what it declares to be its origins, its future and its promise, and to live all that responsibly. If, as Europe has always claimed, this promise has truly as its object the future of humanity as whole, then postcolonial thought calls upon Europe to open and continually relaunch that future in a singular fashion, responsible for itself, for the Other, and before the Other.

The 1978 exhibition was the proud accomplishment of artists and Palestinian militants, in other words, visionaries and dreamers who imagined museums that could incarnate the causes they were fighting for. Museums without walls, or 'in exile', constituted via donations from artists, presented in the form of touring exhibitions, destined to travel the world until the historic change they were fighting for became real. The International Art Exhibition for Palestine, like the International Museum of Resistance for Salvador Allende and the Artists of the World Against Apartheid, began with artists who believe that art is at the heart of everyday life, in streets, cities, schools and homes, at the herald of political change, and with militants who believe that political change is impossible to imagine without artists. Until it was destroyed, The International Art Exhibition for Palestine embodied that common postcolonial modernity, or at least its possibility. The Art Against Apartheid collection lies in the storage rooms of the University of Western Cape. Only the International Museum of Resistance for Salvador Allende has actually become a museum in Santiago de Chile.

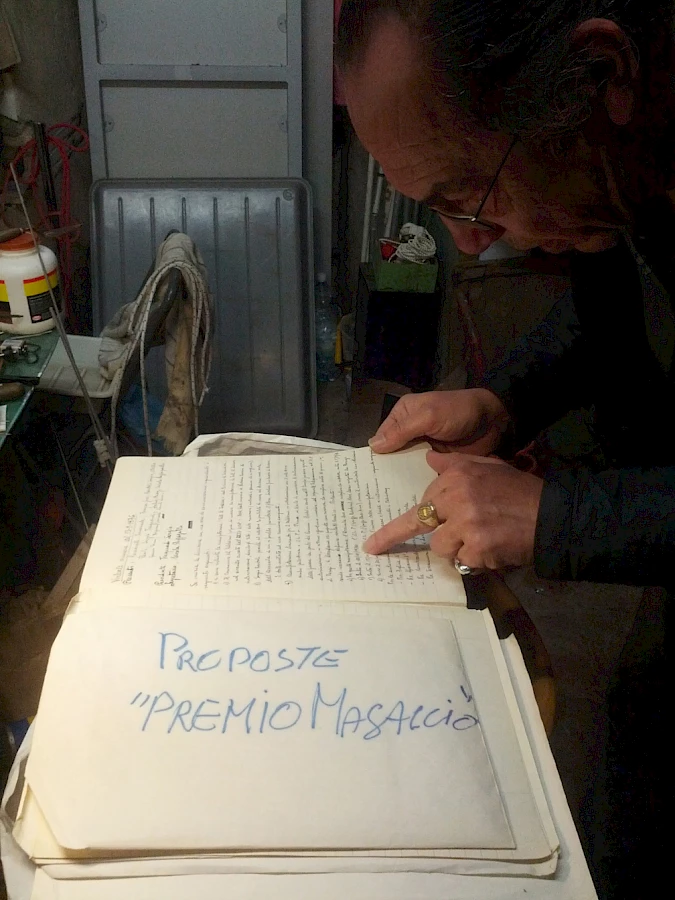

Sergio Tranquandi at his studio. Courtesy: Kristine Khouri.