Constructing a Scottish Internationalism

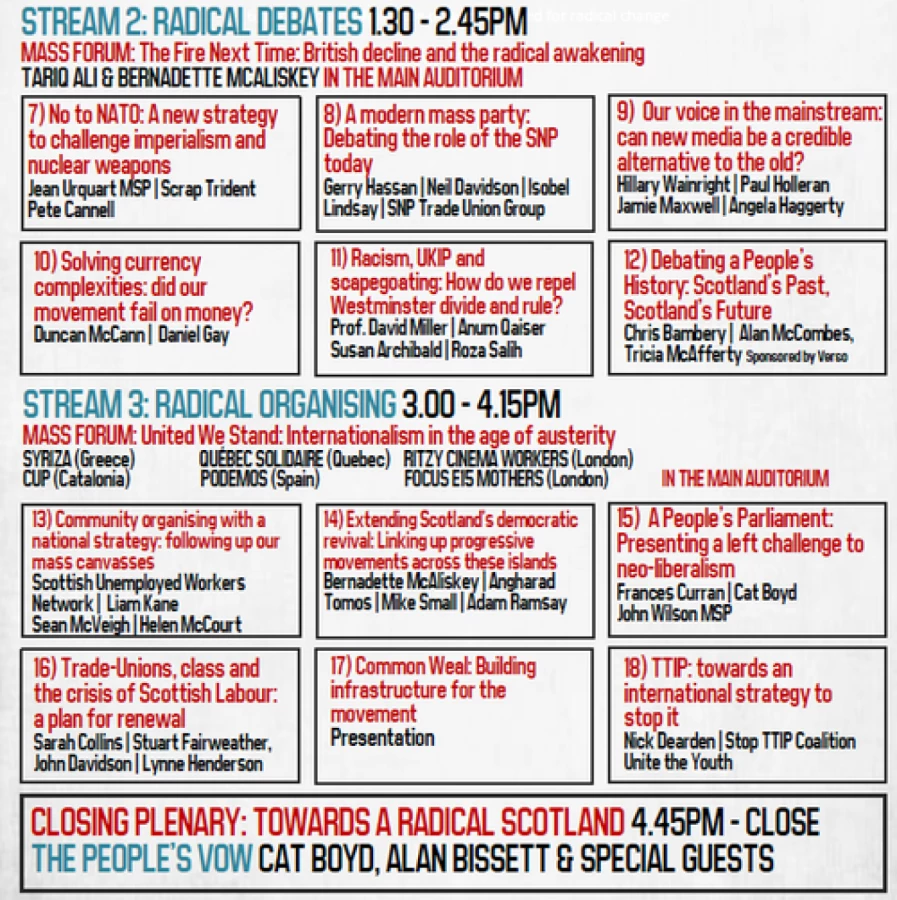

Image taken from http://radicalindependence.org/2014/11/14/conference-timetable-speakers.

It is nearly 2 months since Scotland voted no to self-determination in what was the first opportunity for residents to express themselves as a national community. That community voted for the continuation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (a mouthful of an official name that bears the scars of its imperial history) by a substantial but not decisive margin. For many, including me, the result was a bitter disappointment. Many who voted to establish a new Scottish state saw a chance to invent appropriate governmental structures for today. There was an underlying understanding, not always articulated clearly, that a 'yes' vote could be an enabling step towards creating the political conditions for a state in Europe in the 21st century and to ask the fundamental political question: how do we want to be governed? The paradoxical tensions between localism and globalism played a role in the final decision but ultimately the majority chose security over experimentation, sending the independence campaigners homewards to think again. This thinking again is where new potential lies.

There was a share of nineteenth century nationalism in the vote but this was never an ethnic battle. All Scottish residents were able to vote in a way that was more inclusive than any European parliamentary election, and though Unionists tried to charge their opponents with 'national socialism' at various points, their strong assertions of exclusive British nationalism only stressed the ongoing need to discuss self-determination in a world in which representation through state structures is unavoidable. Thus it was that the morning after the vote felt like a defeat for possibility and the renewal of a civic pact between government and governed, especially in the depressingly moribund landscape of northern Europe. Yet out of the ashes of defeat something remarkable seems to be happening: the opportunity to develop a contemporary narrative around independent statehood, and to construct a new civil society, discursive and participative from its beginnings. These ambitions rhyme much more with the unravelling of the neo-liberal hegemony as seen in countries like Spain (Podemos) or Greece (Syriza) than in older nationalist uprisings and it is why Britishness appears increasingly outdated. The core issue today is how democratic structural change can be achieved, not only in the remaining British Empire but elsewhere too, so that it reflects the needs of a networked, mobile society that also craves lost security and identity. Optimistically speaking, what is on the agenda is a geocultural shift in Scotland that can join with other decolonising shifts in the civil societies of European states. The shift here could be called Scottish internationalism - that is a focus on a Scottish identity in relation to the rest of the world (and not only to imperial Britain). In short, it is about becoming A place in the world and not THE central place for the world as claimed, often unconsciously by Europe and/or Britain by way of their collective colonial traditions.

While the etiolated defenders of the British Unionist establishment must have hoped for a return to Scottish self-pitying retrospection, or the misplaced comfort of nationalist roots after the defeat, what is emerging so far is something counter-intuitive to their conservative mind-set. Where they would wish to decree that a side-lined national community should now settle for the embrace of the bigger, more secure and unchangeable unity of Great Britain; the debate about how Scots want to be governed is ripening and becoming more complex by the week.

This is partly a result of the referendum campaign itself. While the political parties – particularly the British Labour Party and the Scottish National Party – tried to control the agendas, it was civil society groups and self-organised initiatives where the real debate took place. Groups like Commonweal; the Radical Independence Campaign, Women for Independence or the cultural alliance National Collective were the sites where radical discussions have emerged, and where the formation of new opinions, rather than the confirmation of existing attitudes, took shape. Especially in underclass communities in industrial Scotland, where the British Labour party has had a free hand since the 1930s, the new groups active campaigning allowed long unrepresented peoples to discover the beginnings of a newly articulated vision for themselves. This vision no longer reflects what was an apparently misplaced loyalty in the former 'party of the workers', beside which Labour's imperative to retain its neo-liberal credentials with global financial interests makes the job of representing this newly active underclass impossible. Because of this crucial geocultural shift, the result has not dimmed enthusiasm, but if anything it has emboldened people to go further and to build out the grassroots civil society that will make state independence a formality.

Where independence failed however was in shifting the allegiance of the Scottish elite. This group has rarely been analysed, hiding under an Imperial British carapace for most of the modern period, and it was instructive to see it emerge into the light of day. The fact that this elite feels no responsibility towards a Scottish internationalist project, and indeed decries it as 'nationalist' is one of the measures of the extent to which the British colonial/imperial mentality still rules in Scotland. Nevertheless, any state needs the support of an elite and the independence movement neither persuaded them that their interests might lie in swapping their loyalties, nor in threatening them with replacement. That will have to change in the future.

What was equally fascinating to observe is the way that the common sense of a community in a broad sense started to transform throughout the campaign. Where people were previously insensitive to the mainstream media's Unionist bias and their assertion that the UK of GB and NI was a natural condition, they began to doubt and eventually to protest directly against their once trusted sources of information. Throughout the campaign both the state broadcaster, the BBC, and the main newspapers tried to portray the battle as one between political personalities (the 'nationalist/separatist' Alex Salmond versus a succession of 'non-nationalist' individuals culminating in the former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown). This tactic both ignored the British nationalism inherent in any pro-UK position and largely refused to respond to any agenda other than those set by the political parties. In doing so, they simply ignored many people's experiences when engaging with the independence debate and those people then started to turn to small, committed and self-funded websites such as bellacaledonia.org.uk; wingsoverscotland.com; newsnetscotland.com. Many of the facts and analysis they uncovered were known, but were effectively swept under the carpet before the referendum. What this geocultural shift has produced is a newly politicised population where British statehood and the status quo as no longer a natural state of being from which only fools and extremists would wish to depart, but have begun a ground for active debate and reconsideration.

In the cultural field, a similar disconnect between the state organs and the grassroots is visible. The official Edinburgh Festival sought to ignore the referendum entirely in the name of artistic autonomy and most of the key 'national' cultural institutions carried on with business as usual. An extensive retrospective multi-site exhibition of Scottish contemporary art called 'Generation' produced some remarkable highlights but failed to develop a new cultural narrative beyond what had been achieved already in terms of a Glasgow-specific artistic voice in the 1990s. It was left to self-organised groups such as National Collective to assert any artistic agency in contemporary politics and some of these people should ideally move into the institutional infrastructure of the country as it must try to accommodate itself to the demands of the new Scottish civil society

Post-referendum, this is what Scottish internationalism might look like. An active civil society reforming and shaping itself as never before leads a series of instituent initiatives that are loosely linked with others elsewhere and are able to speak out over the internet as well as to organise events, mass canvases, conferences and debates throughout Scotland . A clear link is made with sympathetic institutions that realise they need to change and together they build a potential social imagination within the artistic community that can effect the political and economic debate. At the point when that quickening geocultural shift becomes a consensus, as all indications suggest it hopefully will, then change will occur. In this process, the debate needs to move beyond the false dichotomy of Britishness or Scottishness to test out what it means to be directly part of an international political, economic and cultural discussion from within Scotland. It needs to project a different vision for a new Scottish constitution that recognises the kinds of participatory democracy that could be constructed in the 21st century and that finds ways to bypass or deconstruct the value systems of both old Empire loyalism and contemporary Capital – everything that could be understood under the term Scottish internationalism.

The future is then strangely more full of potential for cultural actors than it would have been with a 'yes' vote. The immediate struggle would then have been to convince the Scottish elite to get on board or quit the new state, and that would have inevitably closed down more possibility than it opened. Perhaps it is ironic that the visionless vote in favour of the UK status quo has arguably released a way of thinking and acting that would have otherwise have been stillborn. Before the referendum, I had hoped that Scotland could gain independence and shape itself according to the newly articulating desires of a civil society in construction; now the necessary strategy is to build the mentality of an independent contemporary society first, and then, and only if necessary, to claim formal independence. For, in all honesty, the official National Party independence campaign was never visionary or radical enough for times like these. The attempt to appease just enough people to stagger over the 50% line meant much that could have been said was marginalised or silenced in the main campaign. It was the grassroots that made independence so appealing and they should now flourish, given all they have achieved. There is a real opportunity to think hard about what it means to act independently and build an internationalist state of mind that transcends the media dictated agenda of economic 'truths' and realist expert opinion in favour of transforming collective consciousness. The relationship between art and wider culture can be hugely significant in shaping this process and the 'no' vote has given artists and art institutions a great challenge and possibility to be part of the social change that is coming, to Scotland and elsewhere, in the next few years.