Demonstration Red Lines, at l'Avenue de la Grande armée, Paris, 11 December 2015. Photo: Clémence Seurat.

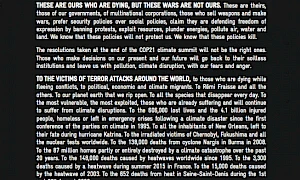

The agreement reached at the close of COP21 on 12 December finally appears to reflect the magnitude of climate change and sets a very ambitious goal: to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Implementing the actions required to attain this target will prove more difficult, because the agreement does not indicate a pathway to follow, address the state of global trade or even mention fossil fuels, whose role in the environmental devastation at hand is abundantly clear.

Meanwhile, different scenarios are taking shape on the various Parties' national stage. Last month, the US Congress passed the Spurring Private Aerospace Competitiveness and Entrepreneurship Act of 2015, more commonly known as the SPACE Act. The law extends the frontiers of commerce to the far reaches of the galaxy in order to "meet national needs", granting US companies and citizens the right to mine natural resources in space and allowing them to lay claim to their newfound riches: "Any asteroid resources obtained in outer space are the property of the entity that obtained them". It is worth mentioning that the passage of the law was applauded by Planetary Resources, a company whose investors include the filmmaker James Cameron and Google's Eric Schmidt and Larry Page.

The SPACE Act is rekindling old dreams of space conquest at a time when many initiatives at COP21 sought to lead the narrative in new directions, away from the colonisation of new lands to exploit, and instead seeking to "leave it [oil] in the ground" or defend the idea that outer space should be approached in terms of the commons, rather than as a business opportunity. Artist Tomás Saraceno's Aerocene project offers a carbon-free alternative to the space-tourism race – an environmental disaster in the making – and warns of the dangers of releasing carbon black into the atmosphere, solely for the enjoyment of the world's wealthiest individuals. Sculptures from Saraceno's project were shown at the Grand Palais and his fuel-free balloons took flight for the first time in the desert of New Mexico, USA, this past autumn.1

Demonstration Red Lines, at l'Avenue de la Grande armée, Paris, 11 December 2015. Photo: Clémence Seurat.

These opposing political visions chart very different paths for the future. As philosopher Emilie Hache suggests in her preface to De l'univers clos au monde infini, in consonance with a science-fiction short story written by Marion Zimmer Bradley, ecology calls for us to bring our focus back down to Earth. It opens up a metamorphic zone that refutes the logic of conquest, with the goal of inventing multiple forms of cooperation that connect us with our environment and bring us closer to others. This 'reterrestrialisation' encourages us to rethink our modes of coexistence and forge alliances with the species2 that populate the Earth, to become earthlings or ' earthbounds'.3

In a lecture entitled 'How to Make a Catastrophe' out of a Disaster given at Bétonsalon, Timothy Morton reminded us that "crisis" is not the right way to think about our ecological situation – it's not a passing event that we will soon emerge from or a disaster external to us. This change is irreversible and catastrophe is our new condition. But rather than being a dead end, it is, in fact, a starting point. And we could begin by "noticing how much we already care".

Translated from French by Ethan Footlik