Ryszard Kisiel, 1985/1986. Courtesy of the Queer Archives Institute.

In a private apartment in Warsaw in 2005, I opened my solo exhibition titled Fags, which was my artistic coming-out and, at the same time, the first openly homosexual exhibition in Poland. Of course, some gay themes had appeared in the works of other Polish artists before, but never in such a direct and conspicuous manner. In the same year, I began publishing an irregularly-issued DIK Fagazine. It is the first, and so far the only, art magazine from Central and Eastern Europe devoted entirely to the subject of masculinity and homosexuality in the broad context of culture and art, with particular focus on the region. For a long time, in Poland, as well as in many other post-socialist States, homosexuality remained taboo after the political transformation; and it was often treated as something that "had arrived from the West". For example, in Ukraine, which is trying to acquire European Union membership, it is not unusual to hear arguments against this accession saying that as a result the country would turn into a "Sodom". This argument is largely present in the region, especially in those countries still under strong influence of the Roman Catholic or Orthodox Church. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Warsaw hosted "Europride" in 2010. This could be perceived as an element of a "rainbow colonisation", in which "Western gays" brought their rainbow flag to Eastern Europe, while a conference accompanying the event was devoted to so-called "pink money" – the purchasing power of the exclusive gay community. As a result, I concluded that there was a serious need to prove that queer culture existed in Poland already during the socialist era, that we were "queer before gay". Consequently, my goal has been to recover this aspect of the past as part of Poland's cultural history in general, not just as an element of queer history.

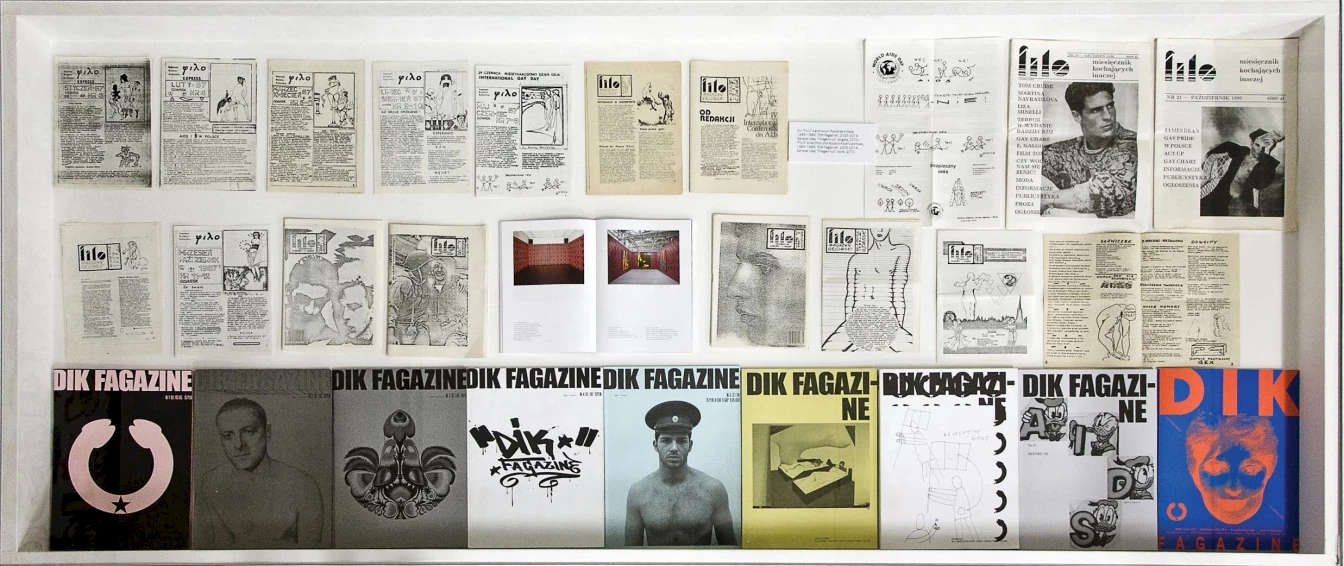

Karol Radziszewski, vitrine (Filo, 1986–1990 and DIK Fagazine, 2005–2014 magazines). Photo: Wojciech Olech. Courtesy of the artist and CoCA in Torun.

DIK Fagazine

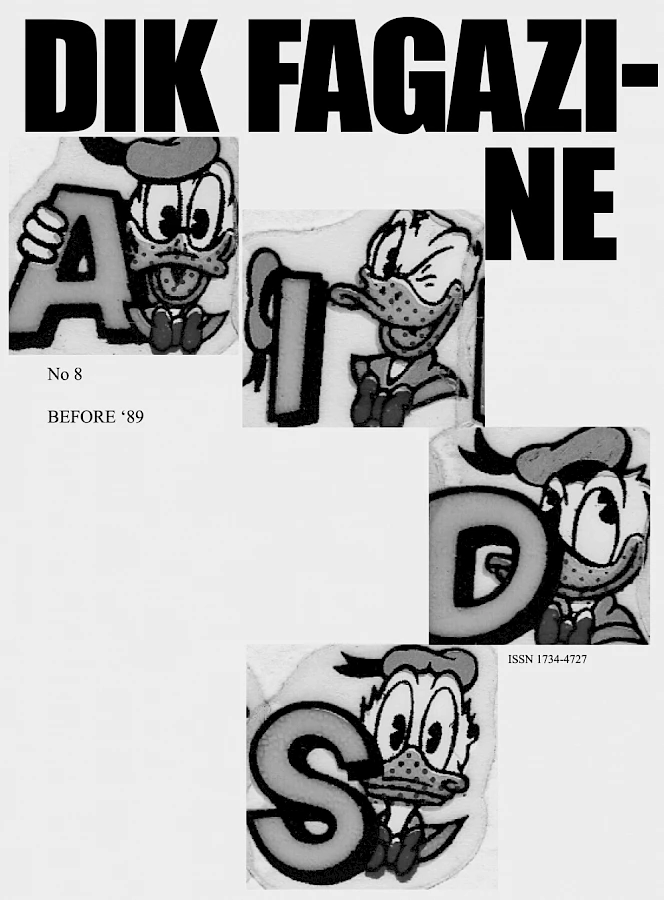

The beginning of my archival research was connected with DIK Fagazine. The magazine gradually evolved from a periodical addressing the current situation in Poland and the Central and Eastern European region, to a platform exploring queer archives that is determined to discover our "queer ancestors". In 2008, I began work on an almost three-year-long project that was a special issue entirely focusing on the life of homosexuals in Central and Eastern Europe before 1989. In the process of researching sources and travelling, I reached many people whom I interviewed. From the outset, it was important for me to confront the Polish experience with that of our neighbours, to sketch a wider panorama of the region. With my collaborators Paul Dunca, Kamil Julian, Pawel Kubara and Jaanus Samma, I looked at several selected countries (Poland, Romania, Estonia, Latvia, Serbia, the Czech Republic and Hungary) in order to trace and compare cruising areas, gay nude beaches, groundbreaking publications as well as reactions to the beginnings of the AIDS epidemic. Despite specific local circumstances in these countries, many of the described experiences proved to be similar, such as a lack of an organised community (with a few exceptions), similar cruising areas (almost always railway or bus station toilets, main city parks, and men's bathhouses), non-existent or very few places addressed exclusively to homosexual clients (clubs or bars), and the emergence of the first publications on the authorities' actions in the effort to prevent the spread of HIV-AIDS.

My primary method was conducting interviews with older people and consulting their private archives (photographs, personal writings) which had usually never been shared before. My work rarely involves visits to libraries; I prefer to focus on direct contact with the witnesses to events and gather their memories. Typically, I would first meet local activists, who would give me information about people I could potentially talk to, and they often suggested new avenues where I could find further material. Thus obtained and recorded audio or video interviews become documents, and the beginnings of an archive.

DIK Fagazine, Issue No. 8 'BEFORE '89', 2011. Courtesy of Karol Radziszewski.

Alternative Sexual History as an Art Practice

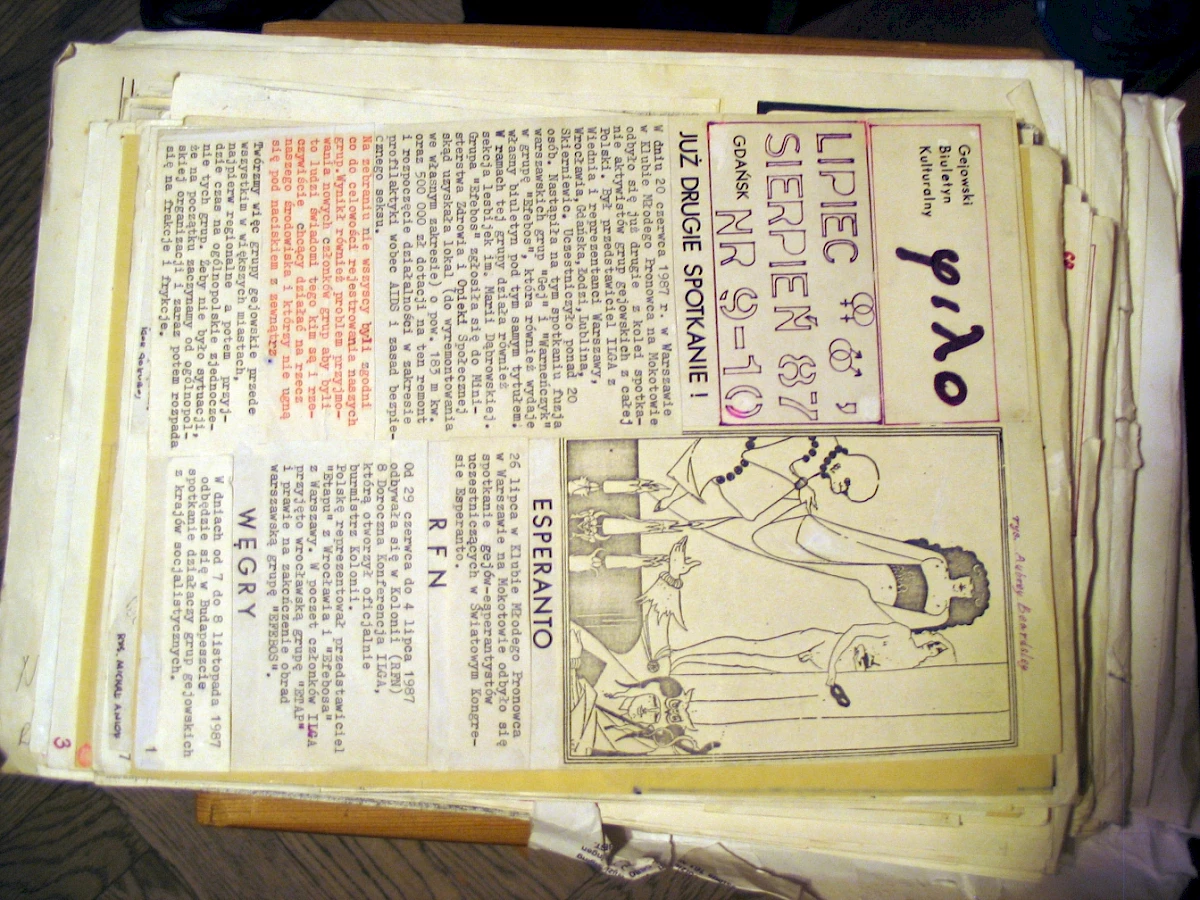

Thanks to work on the issue entitled "BEFORE '89" (published in 2011), I met Ryszard Kisiel and discovered the existence of Filo – the first socialist-era gay magazine devoted to non-heteronormative issues in this part of Europe, founded by Kisiel and distributed semi-legally among his friends and acquaintances.1 Consequently, DIK Fagazine reprinted original mockups from Filo, our "newly-discovered ancestor". During consecutive meetings with Kisiel in his tiny flat in Gdańsk, I was able to explore his vast archives, and learn new facts and various aspects of his activity. On one occasion, he produced a plastic bag full of meticulously labelled little boxes with a collection of nearly 300 coloured slides. These contained documentation of the photo shoots which Kisiel realised with his friends in someone's private apartment. The slides dated from late 1985 and early 1986, as a direct response to Operation Hyacinth (a comprehensive campaign carried out by the Civic Militia in the Polish People's Republic, which consisted in the gathering of data on Polish gay men and their community, as a result of which approximately 11 000 personal files were registered). The discovered slides provide specific visual evidence and contradict the stereotypical way of thinking about life in the Polish People's Republic. They counter the image of a homosexual as a persecuted victim, revealing a large potential of positive energy, uninhibited sexuality, invention, irony and self-irony (even towards such taboo topics as AIDS). Kisiel's archive also allows us to take a fresh look at the reality of the socialist era, because despite obvious contradictions between the East and the West in that period, strikingly cosmopolitan references and similarities can be noticed in the international "sexual avant-garde" and its iconography.2

Mockups of the Filo magazine, 80s. Courtesy of the Queer Archives Institute.

Ryszard Kisiel, Leba, Poland, end of the 70s. Courtesy of the Queer Archives Institute.

For the last few years, I have been working on an art project titled Kisieland which is a long-term undertaking drawing on Kisiel's archive. It began with recording conversations and ordering the digitisation of Kisiel's slides, which have since been presented at lectures and in printed form as part of several exhibitions.3 A publication presenting the entire collection is planned in the future. In 2011, I invited Ryszard Kisiel to my studio, where he decided to return to the role of creator after twenty-five years. The film (Kisieland, 2012, 30min) which recorded this action confronts memories with Kisiel's present image, as he confronts a young model face-to-face. In addition to telling the story, the documentary presents a large number of digitised archival photographs. The "AIDS" cycle (wallpaper, paintings, graphics, and posters) of this project echoes Ryszard Kisiel's collage of Donald Duck stickers included in an issue of Filo in the late 1980s as well as the "Imagevirus" project by the collective General Idea, which travestied Robert Indiana's iconic work called LOVE. As part of the Kisieland project, I organised a special event during PERFORMA 13 in New York – a discussion to which I invited both Ryszard Kisiel and Avram Finkelstein (the founding member of Gran Fury and ACT UP, the AIDS advocacy group), thus confronting Eastern European and American narratives on the beginnings of the AIDS epidemic. The meeting also included a performative reading of excerpts from Boris L. Davidovich's Serbian Diaries, which describe that moment in history from the perspective of early 1980s Belgrade.

Locating Kisiel's archive in the context of art is an opportunity to restore/reveal the past, and recover its critical potential. It is also complements Polish visual history by supplying it with hitherto ignored material.

Ryszard Kisiel, Bulgaria, 1980. Courtesy of the Queer Archives Institute.

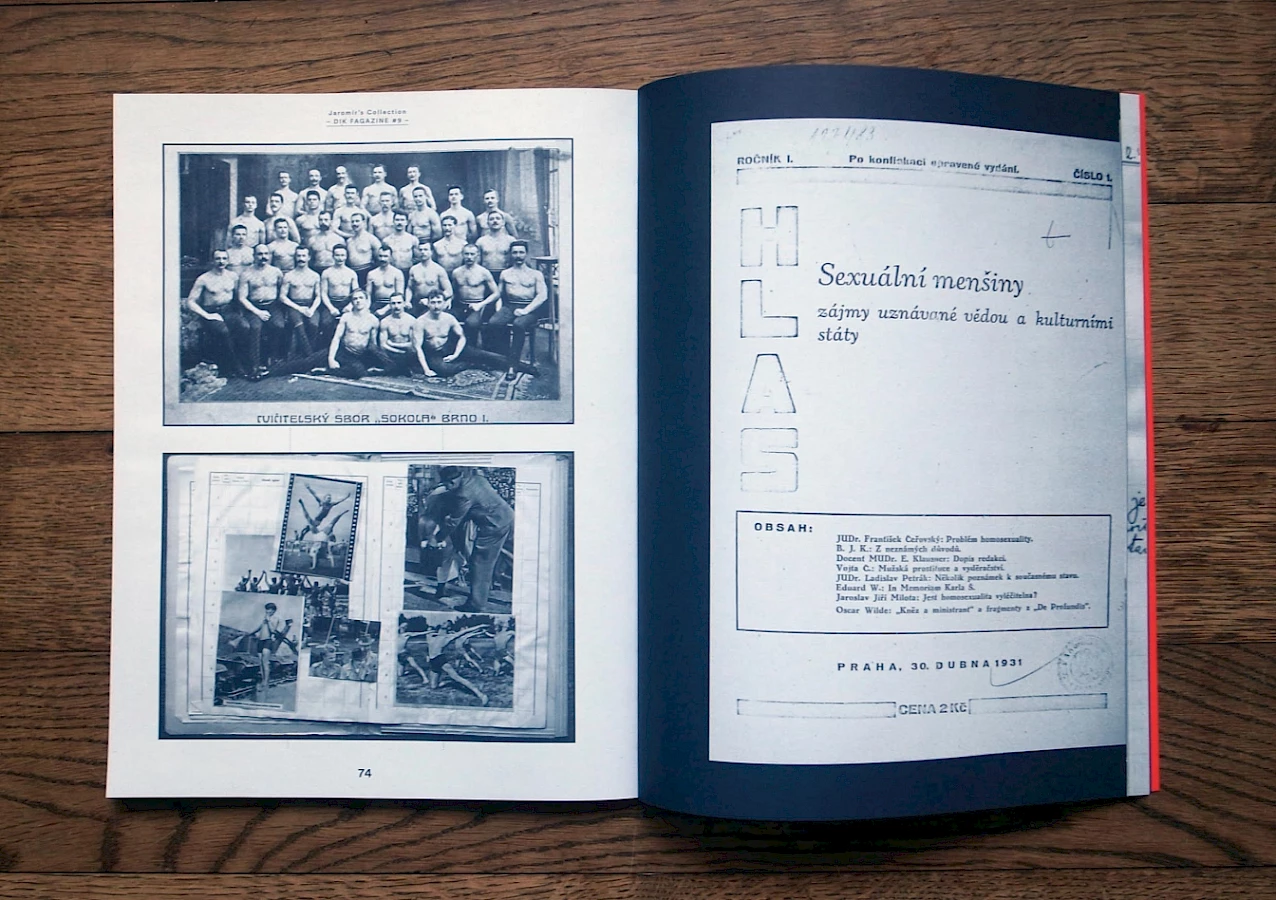

Archival images and the first issue of Hlas magazine (1931) reproduced in the DIK Fagazine, No. 9, 'Czechoslovakia' issue (2014). Courtesy of the Queer Archives Institute.

Ryszard Kisiel, 1985/1986. Courtesy of the Queer Archives Institute.

Broadening perspectives – Queer Archives Institute

My work with archives has expanded from the initial highly local, Polish, context, to the gradual inclusion of neighbouring countries in search for commonalities, and the current attempt to reach a broader perspective. Travelling to Brazil and exploring the question of Brazilian queer archives, I found some similarities with the results of my research conducted so far. The particularly topical subject of the "Global South" repeatedly overlaps, criss-crosses and dovetails with the "Global East". What emerges is a story of a "global province", timidly trying to discover its own language and create its own independent identities. There have been previous projects comparing Eastern Europe with Latin America, for example the recent exhibition Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960–1980 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2015, that focused on parallels and connections among artists. However, so far I have not come across any similar attempt to assemble queer archives in a specific given context. Such juxtapositions seem to me to be an interesting experiment. What I concentrate on is rather a similar context, certain limitations, as well as often a vestigial character of (hi)stories that are yet to be told.

It is to subject matter of this kind that I would like to dedicate my newest project, "Queer Archives Institute" (QAI).4 On one hand, it is intended to sum up my practice so far, and, on the other, to try and establish permanent co-operation with partners (such as artists, activists, academics, and local non-governmental organisations). The aim of the project will be to gather queer archives from various geographic regions, especially those which are "peripheral", either literally or symbolically colonised, and make them accessible as well as subject to artistic interpretation. QAI's main platform will be a website5 gathering digitised materials ranging from scans of archival photographs, magazines and publications, through audio and video interviews, to texts analysing related concepts and methodologies. Owing to the entirely private character of the initiative, at first, by necessity, the scale of the undertaking will be limited; however, eventually it is meant to be more far-reaching.

Importantly, in addition to the process of cataloguing and geographical/ chronological ordering, I will create a system to enable thematic searches which will form multi-level hypertextual connections between materials from geographically distant places. Thus the digital dimension of QAI needs be complemented by a "material" one: by organising or co-organising exhibitions presenting the collected materials, sometimes with the participation of invited artists. On a smaller scale, I have already started to use such strategies in various presentations6 where archival visual materials, such as voyeuristic photographs from very different beaches, are juxtaposed side by side. Similarly, I have showcased the first LGBTQ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Queer) publications to be issued in various countries, or artefacts (posters, leaflets, graphics, books) related to the beginning of the AIDS epidemic.

Karol Radziszewski, Kisieland, installation view, Centre of Contemporary Art Znaki Czasu in Torun, 2014. Photo: Wojciech Olech. Courtesy of the artist and CoCA in Torun.

Parallel With the Global Canon

In the post-socialist states particularly, or other contexts marked by dictatorships for example, where some historical threads were broken or could never emerge, there has been an attempt to build new national narratives. Recent history is being largely constructed today, and sometimes manipulated. I am interested in this appendicising, rewriting, revising, but from a very personal perspective. Decolonising history through queer archives has become for me a mission, an "identity project". The work has political, or even activist potential for me. I often feel that by working on every next project, text or exhibition, I can do more than by marching and demonstrating in the streets. I am interested in alternative versions of well-known stories and questioning canonical narratives. This subversive strategy aims to change the future image of the hitherto-created reality. This is connected with discovering the local Eastern-European identity, shaped in parallel with the global canon: the first Czech magazine dedicated to homosexuality was published in 1931,7 so why should we always have to rely primarily on American or British zines from the 1960s and 1970s?

Translated by Ewa Kowal

References:

Basiuk, T. 2011, "Notes on Karol Radziszewski's Kisieland"/"Uwagi na temat projektu Kisieland Karola Radziszewskiego", in K. Pijarski (ed.), The Archive as a Project, Fundacja Archeologia Fotografii, Warsaw.

Davidovich, B.L. 1996, Serbian Diaries, Heretic Books, London.