Climate Risks, Art, and Red Cross Action. Towards a Humanitarian Role for Museums?

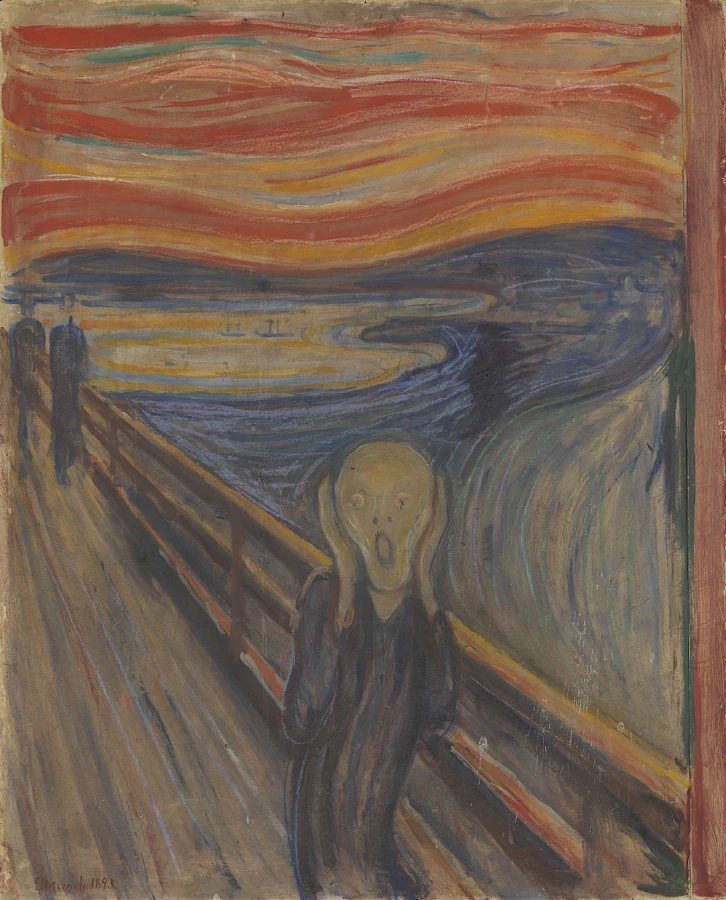

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893. Photo: Børre Høstland, The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo.

This is an open invitation to the L'Internationale community of museums and civic institutes where art is used for public benefit: How can you and the Red Cross work together for inspiration, reflection and debate on climate issues? How can we help accelerate action by influencing culture? Can we mobilise the power of humanity to address climate risks, through innovative uses of art?

When the Krakatau volcano exploded in Indonesia in 1883, it sent 20 billion tons of sulphate particles to the upper atmosphere, casting shadows. During the following months, the partial blocking of sunlight changed rainfall and temperature patterns around the world, and tainted the sunsets in Norway. Edvard Munch wrote of "clouds turning blood red. I sensed a scream passing through nature; it seemed to me that I heard the scream. I painted this picture, painted the clouds as actual blood. The colour shrieked. This became The Scream.

We know that a different phenomenon has been altering our atmosphere since before Munch's painting: our burning of fossil fuels has been adding heat-trapping gases to the air, at an accelerating rate (about forty billion tons of CO2 last year alone, and rising...). We are in trouble: greenhouse gases can stay up in the atmosphere for a century, slowly but surely warming up air and waters, with inevitable and somewhat predictable changes in winds, oceanic currents, and therefore forcing us to experience the unprecedented.

The science is unequivocal: our global climate is changing, raising sea levels and significantly increasing the risk of severe floods, droughts, heat-waves, forest fires and other extreme events.1 Nature is already screaming at us. While the main greenhouse gases are not visible to our eyes, we are seeing the impacts of a changing climate on the very people who have done the least to cause the problem. Climate change is a humanitarian issue, and the humanitarian sector needs to rethink how we work, expanding our collaboration with organisations that can help people understand and address the problem – and what can be done about it.

It is crucial to ensure that vulnerable communities are prepared for the rising threats. While much remains to be done, collaborations between people at risk, disaster managers, government agencies, donors, scientists and other stakeholders in risk management are making remarkable progress. In Bangladesh for example, where past tropical cyclones have led to massive death tolls, improved systems are saving lives by turning early warnings into early2 action. The Bangladesh Red Crescent and partners have tapped into the artistic inclinations of the population by using drama, song, poetry and visual3 arts among its advocacy efforts to enhance cyclone awareness and motivate communities in disaster risk reduction.

At the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre we have been carrying out our mission to help address the humanitarian consequences of climate change and extreme events since 2002. Experience has taught us that science and humanitarian considerations alone seem to not be enough to inspire ambitious thinking and action needed given the scale of the problem.

Red Cross Argentina, Planetarium installation. Still from a video.

Innovative collaborations with artists have shown their humanitarian4 power. When the Argentinean Red Cross was trying to help flooded rural communities in the northern province of Chaco, it decided to embark on an unusual endeavour: a collaboration with designers and government authorities in Buenos Aires. The resulting installation, Casa Inundada, 2009, consisted of a submerged home in the capital city, mounted in a pond next to the Planetarium's modern building. Art brought the message of solidarity to the heart of the city, helping to raise awareness of thousands of passer-bys, and to millions through TV and other5 media.

Filmmaking also offers unique opportunities to help address the causes and consequences of climate change. In addition to professionally produced films, recent initiatives have explored more interactive ways to use audiovisual tools. For example, participatory video involves a group or community in shaping, creating and filming their own film. It establishes trust and has the potential to create spaces for transformation. The Climate Centre has worked with partners to make participatory videos on climate change in Ethiopia,6 Malawi7 and beyond, with illiterate subsistence farmers becoming filmmakers and promoting the dissemination of new farming practices that can help their peers adapt to changing conditions and promote food security. An additional innovation was offered during the UN Climate Conference in Doha (Qatar, 2012), where participants at the Development and Climate Days (D&C Days) were invited to first become film critics of existing conventional and unconventional climate-related videos, and then storyboard proposed short films together – like the Sudanese negotiator and the British researcher crafting a movie concept in the publication Beyond the Film.8

Music also has much to contribute to humanitarian work in a changing climate. In addition to well-known campaigns supported by celebrities, there is room for more tailored approaches. For example, a sound art miniature competition co-convened by the Climate Centre and CEIArtE9 invited musicians to create 'soundscapes' about the growing risk of mosquito-borne diseases like malaria and dengue, which are showing new regional and seasonal patterns due to changing rainfall and temperature conditions. The winning submissions evoked the pervasive buzz of mosquitoes changing in space and time, disrupting and even threatening the listeners. The role of music was further explored at the D&C Days during the UN Climate Conference in Warsaw (Poland, 2013): a session was dedicated to how music improvisation10 can teach key lessons to climate risk managers.

A rapidly growing, exciting new endeavour is combining creative design and system dynamics modelling: participatory games11 that embody the feedbacks, thresholds, delays and especially the trade-offs involved in disaster risk management. Games involve decisions with consequences, and consist of a sequence of interesting choices. Serious yet fun gameplay sessions have been facilitated in over a thousand events, ranging from gender and climate in rural Kenya12 to hurricane preparedness at the White House,13 inviting participants to reflect on potential individual and collective choices for managing risks in a changing climate. A particularly exciting approach is offered by engagement games,14 where play actions are taken not in a fictional setting but in the real world, in ways that enable people to understand and change their reality.

For example, we designed the game UpRiver in collaboration with Engagement Game Lab (EGL) to help Zambian farmers living along the floodplains of the Zambezi River to understand and contribute to flood warnings, providing incentives to monitor and report river levels in their village, and make predictions based on available information from upstream. UpRiver can improve science-based predictive models, as well as increase the trust of communities in early warning systems. Games are increasingly considered an art form, and have a lot to contribute to both museums and the Red Cross to help engage people in experiencing the emotional and intellectual complexity of changing realities.

Tomás Saraceno, Aerocene, a model try-out at the artist's studio, October 2015. © Studio Tomás Saraceno, 2015.

Imagine you are a Red Cross worker. The world of museums seems irrelevant for your mission to address climate-related threats around the world. An unusual opportunity arises: you can propose via an out-of-the-box activity in the context of the UN Climate Conference in Lima in December 2014. What can you do to help event participants rethink the future? With support from numerous partners, the Climate Centre tried something new: Under the vision and guidance of Tomás Saraceno,15 a team of local volunteers set to work, including artists, students and Red Cross youth, as well as grandmothers and children from the slums near Parque Wiracocha. They collectively constructed a large, lighter-than-air sculpture made of plastic bags that would otherwise be trash.

UpRiver, Zambia. Photo: Wade Kimbrough, Engagement Lab. Participatory games can help people and communities inhabit the complexities of changing climate risks. The game UpRiver in Zambia has inspired farmers living on the Zambezi River Floodplain to embrace and contribute to early warnings.

Named Intiñán16(a Quechua word meaning "way of the sun"), the sculpture aimed to harness the sun's power to make our thinking and action take flight. No need for helium or a burning flame feeding off fossil fuels: Just sunlight and the flame of motivated volunteers.

While Intiñán was absorbing the sun's power, many participants in suits and neckties removed their shoes and crawled into this cathedral of light made of simple plastic bags. An artistic vision was uniting Lima's shantytown dwellers with Nobel-prize-winning scientists, Bangladeshi community organisers, TV crews, European donors and Ugandan disaster managers, all bonding and reigniting their commitment to a better world while looking up to the luminous world of possibilities. On 7 December, 2014, Intiñán became lighter than air and lifted off the ground, in the middle of an event that included former heads of state, national ministers, and development workers from all continents. Intiñán incarnated what our world needs: We can mobilise the power of humanity, embracing science and art to rekindle our relationship to the world.

Tomás Saraceno, Becoming Aerosolar at Country Club Lima, Peru, 2014. Hosted by "Development & Climate Days, 2014: Zero poverty, Zero emissions. Within a generation." © Studio Tomás Saraceno, 2014. The invitation to an artistic experimental performance, by artist Tomás Saraceno, said: “Join us to create and celebrate solar-powered, lighter-than-air sculptures, and engage in rethinking possible futures”. The result, in collaboration with Red Cross partners, was Intiñán, which took flight harnessing sunlight and the flame of motivated volunteers.

This collaboration between artist Tomás Saraceno and the Red Cross was featured at the Becoming Aerosolar exhibition in Vienna's 21er Haus in 2015. Its spirit carries on with the artist's new endeavour, Aerocene, an installation on view between 4 and 10 December at the Grand Palais for the 2015 UN Climate Conference in Paris. The Climate Centre has been invited to present insights at an Aerocene symposium on 6 December, hours after another out-of-the-box participatory session entitled Taste the Change, which will explore our climate choices through food at the upcoming Development & Climate Days – in collaboration with the Senegalese culinary artist Pierre Thiam.

So what can museums and artists do to help address the humanitarian consequences of climate change? The best answers, of course, can only emerge from the art community itself. We trust that the exploration of this question is gaining momentum, and from the Climate Centre we look forward to contributing. Some thoughts for your consideration include of course the obvious task of reducing the carbon footprint of art-related endeavours, not only in terms of the lightbulb efficiency of museums but also other, more symbolically powerful aspects – from the materials and messages of selected artwork to the choice and climate-responsibility profile of sponsors. At the practical level there can be new or revised disaster management plans, examining the threats posed by extreme rains, winds, temperatures and other climate-related issues and what can be done to reduce losses of artwork as well as improve the resilience of workers, guests and local communities. At a deeper level, museums, artists and other stakeholders in the world of culture could help humanity by creating exhibits, installations, and other initiatives aimed at helping us all see with new eyes on the climate issue with new eyes . We need to infuse creativity into humanitarian work and beyond, expanding the range of what is perceived as real, and what is perceived as doable.