Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

This hope no doubt seems naive, even impossible, to many. Nevertheless, some of us must rather wildly hold to it, refusing to believe that the structures that now exist will exist forever. For this, we need our poets and our dreamers, the untamed fools, the kind who know how to organise.

–Judith Butler, 13 October 20231

Since 7 October, across European public spheres, rampant censorship and self-censorship has infected institutions and been internalised by cultural producers. The refusal by western governments and media to use words pronounced by the world’s leading human rights bodies to name the decades-long occupation and apartheid and the unfolding genocide of the Palestinian people also pervades the cultural sectors. The expression of grief, anger and sadness at the killing in Palestine and Israel is even contested, while the basic humanitarian appeal for a lasting ceasefire has been opposed. Consequently, the agents of the European political and public spheres are restricting freedom of expression, rather than mediating conversations across differences.

Censorship and a heightened contestation of language reveals how interpellation is acting on, and within, public spheres, whereby the ideological positions of state and media infrastructures become internalised by citizens and articulated as their own. As this interpellation takes hold and actors are reduced to passive rather than thinking subjects, the capacity of public spheres to be shaped or moved by discourse and debate is at stake. At the same time, the global role of Europe has come under question, as it has failed to adopt any constructive or even meaningful position, either displaying its underlying acceptance of dehumanization or actively taking the side of colonial domination. International alliances and relations – including those within our network of museums, universities and arts organisations – are confronted anew with how the traces of coloniality and imperial violence, exerted from multiple directions, cross their structures.

This is where we all are – even as we are touched in different ways and to different degrees. We, the editors of L’Internationale Online, are unwilling, or unable, to write with an institutional voice, assumed or imposed. That voice, wherever it may be located, is alien. We write, however, in an attempt to find some common expression among specific, situated and generational experiences, with the aim to mobilise critical voices and to work and think collectively, beyond the interpellation of governments and the media.

The demands of the Palestinian liberation movements on cultural sectors are clear. If our institutions cannot meet them, we must acknowledge the failures and limits of our spaces, entangled as they are in broader political mechanisms. The immediate path, then, for a publishing platform like L’Internationale Online, is to utter, to speak, to work with subjectivities and situated knowledges – our own and others’. The material we plan to publish over the coming weeks and months will not be able to adequately address the extent of the daily tragedies, the contortions of debate, the historical implications of witnessing and speaking to genocide. Still, the texts, films and sounds offer a possibility to work in excess of institutional positions and to contribute to an ongoing reshaping of public spheres and critical discourses.

In addition, we see the long-term task for the cultural sphere to be to reformulate the vocabularies that have acted as the scaffolding for rhetorical frames and political positions within artistic fields, in order to overcome the weaponizing and imposed foreclosure of language. Any attempts at this will have to foster a wide appeal, building a popular front that could have the approach, the attention and the drive to effectuate such change, while knowing that such moves might lead to a fragile, tumultuous phase of in-betweenness.

Following Donna Haraway’s call to ‘think we must; we must think’ – as a struggle against Denkverbot and the shutting down of discursive spaces and practices – and after Fred Moten’s summoning of ‘collective study’, we embark on multiple lines of inquiry to navigate the shifting grounds and registers of the present conjuncture. Among these many trajectories we will turn to feminist decolonial thought and praxis to analyse the ongoing case of Israeli settler colonialism and its military and carceral regimes. We will seek to draw attention to the asymmetries in power relations and the instrumentalization of rhetorical frames, their origins and their consequences in the European context. And in a forthcoming article Ovidiu Tichindeleanu outlines the repression within European public spheres and the entanglement of this with imperial histories. As acts of solidarity, we will platform the work of artists, poets, musicians and film-makers working past the limits of language to think through the present and its myriad implications and inflections. The publishing here will be necessarily partial and incomplete. It is not approached as a declaration, or an answer. Rather, to recall Audre Lorde, we approach it as an exercise in finding the words we do not have.

Related activities

-

Institute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb

Red, Green, Black and White

A performative inquiry by Institute of Radical Imagination and MSU Zagreb

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–MACBA

Song for Many Movements: Scenes of Collective Creation

An ephemeral experiment in which the ground floor of MACBA becomes a stage for encounters, conversations and shared listening.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

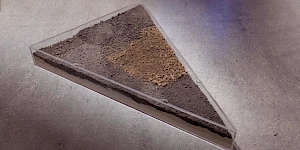

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–VCRC

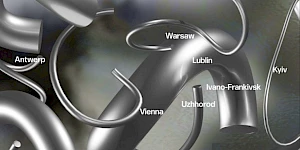

Kyiv Biennial 2023

L’Internationale Confederation is a proud partner of this year’s edition of Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Where are the Oases?

PEI OBERT seminar

with Kader Attia, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Emily Jacir, Achille Mbembe, Sarah Nuttall and Françoise VergèsAn oasis is the potential for life in an adverse environment.

-

MACBA

Anti-imperialism in the 20th century and anti-imperialism today: similarities and differences

PEI OBERT seminar

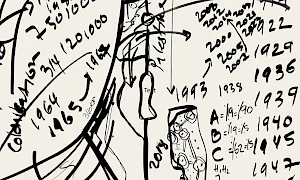

Lecture by Ramón GrosfoguelIn 1956, countries that were fighting colonialism by freeing themselves from both capitalism and communism dreamed of a third path, one that did not align with or bend to the politics dictated by Washington or Moscow. They held their first conference in Bandung, Indonesia.

-

Institute of Radical ImaginationMuseo Reina Sofia

Cinema as Assembly

Cinema as Assembly investigates cinema as a space of social gathering and political engagement that prefigures and enacts forms of living beyond colonial capitalism.

-

21 Jun 2023 –6 Jul Van AbbemuseumMaria Lugones Decolonial Summer School

Recalling Earth: Decoloniality and Demodernity

Course Directors: Prof. Walter Mignolo & Dr. Rolando VázquezRecalling Earth and learning worlds and worlds-making will be the topic of chapter 14th of the María Lugones Summer School that will take place at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven.

-

23 Apr 2023 –30 Sep 2024 MSNArchive of the Conceptual Art of Odesa in the 1980s

The research project turns to the beginning of 1980s, when conceptual art circle emerged in Odesa, Ukraine. Artists worked independently and in collaborations creating the first examples of performances, paradoxical objects and drawings.

-

24 Aug 2024 –30 Aug Moderna galerijaZRC SAZUSummer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school is organised by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in partnership with ZRC SAZU (the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts) as part of the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons.

-

15 Feb 2024 –15 Mar Moderna galerijaZRC SAZUOpen Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

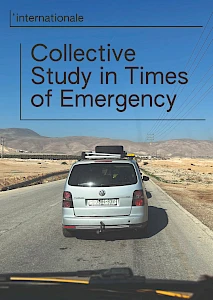

23 Jan 2025 HDK-ValandBook Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Gothenburg

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and Mills Dray (HDK-Valand), 17h00, Glashuset

-

28 Jan 2025 Moderna galerijaBook Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Ljubljana

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Bojana Piškur (MG+MSUM) and Martin Pogačar (ZRC SAZU)

-

27 Nov 2024 WIELSBook Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Subversive Film and Alex Reynolds, 19h00, Wiels Auditorium

-

10 Oct 2025 –18 Jan 2026 Kyiv Biennial 2025

L’Internationale Confederation is a proud partner of this years’ edition of the Kyiv Biennial.

-

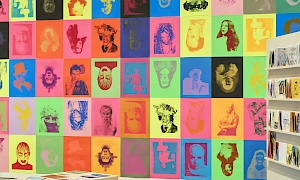

6 Nov 2025 –6 Apr 2026 MACBAProject a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica

Curated by MACBA director Elvira Dyangani Ose, along with Antawan Byrd, Adom Getachew and Matthew S. Witkovsky, Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica is the first major international exhibition to examine the cultural manifestations of Pan-Africanism from the 1920s to the present.

-

13 Jun 2025 –21 Sep M HKAThe Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

10 Nov 2025 –16 Nov MACBAMuseo Reina SofiaSchool of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organisations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

25 Mar 2025 NCADBook Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Dublin

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and members of the L'Internationale Online editorial board: Maria Berríos, Sheena Barrett, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Sofia Dati, Sabel Gavaldon, Jasna Jaksic, Cathryn Klasto, Magda Lipska, Declan Long, Francisco Mateo Martínez Cabeza de Vaca, Bojana Piškur, Tove Posselt, Anne-Claire Schmitz, Ezgi Yurteri, Martin Pogacar, and Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, 18h00, Harry Clark Lecture Theatre, NCAD

-

8 May 2025 –9 May Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

25 Apr 2025 Museo Reina SofiaPoetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

Related contributions and publications

-

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’ad27 Mar 2024 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II: Learning Palestine

Learning Palestine Group12 Jan 2024 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I: Learning Palestine

Learning Palestine Group8 Dec 2023 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the Present -

Live set: A Love Letter to the Global Intifada

Precolumbian13 Jun 2024 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencySonic CommonsPast in the PresentMACBAEN es -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana Anani10 Sep 2024 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise Vergès21 Dec 2023 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the Present -

Everything will stay the same if we don’t speak up

L’Internationale Confederation17 Apr 2024 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyStatements and editorialsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsEN ca -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin Pogačar14 Nov 2023 ... and the Earth alongClimatePast in the Present -

Statement on the attack on Kakhovka Water Dam

L’Internationale Confederation11 Jun 2023 Statements and editorials -

The Kitchen, an Introduction to Subversive Film with Nick Aikens, Reem Shilleh and Mohanad Yaqubi

Nick Aikens, Subversive Film13 Jul 2023 lumbungPast in the PresentVan Abbemuseum -

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu6 Dec 2023 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the Present -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana Piškur22 Jan 2024 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick Wilson20 Dec 2023 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the Present -

In solidarity with all the people affected by the earthquake in Turkiye and Syria

L’Internationale Confederation13 Feb 2023 Statements and editorials -

Public letter on WHW termination as directors of Kunsthalle Wien

L’Internationale Confederation10 Jan 2023 Statements and editorials -

Statement in support of documenta fifteen

L’Internationale Confederation27 Jul 2022 Statements and editorialslumbung -

Never Again War!

L’Internationale Confederation28 Feb 2022 Statements and editorialsEN es pl sl sv ca nl uk -

Statement on the dismissal of Alistair Hudson

L’Internationale Confederation27 Feb 2022 Statements and editorials -

L’Internationale Public Statement on the recent events at MACBA

L’Internationale Confederation21 Jul 2021 Statements and editorialsMACBA -

L’Internationale statement: Towards a healthy society

5 May 2020 Statements and editorials -

Standing up for the rights of all artists to free and independent expression

L’Internationale Confederation11 Dec 2018 Statements and editorials -

Tearing Down Bridges – Turkey's Withdrawal from Creative Europe

L’Internationale Confederation29 Sep 2016 Statements and editorials -

Of Cats and Canary Birds: Statement in Support of Lunds Konsthall

L’Internationale Confederation17 Dec 2015 Statements and editorials -

How Much Austerity Can Europe Endure?

L’Internationale Confederation4 Jul 2015 Statements and editorials -

L'Internationale supports Walid Raad, Andrew Ross and Ashok Sukumaran after the recent ban on their entry to the UAE

L’Internationale Confederation21 May 2015 Statements and editorials -

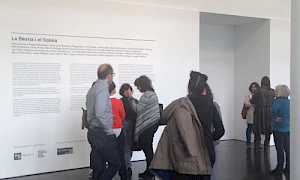

L'Internationale statement in support of the decision to open "La Bestia y el soberano" (The Beast and the Sovereign)

L’Internationale Confederation21 Mar 2015 Statements and editorialsMACBA -

Artists for Kobanê: An online auction to benefit refugees from Kobanê

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board3 Dec 2014 Statements and editorials -

L'Internationale statement in support of MNCARS

L’Internationale Confederation4 Nov 2014 Statements and editorialsMuseo Reina SofiaEN es sl nl tr -

New online platform for research, resources and discussion

L’Internationale Confederation17 Sep 2014 Statements and editorials -

The Veil of Peace

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu31 Oct 2023 Past in the Presenttranzit.ro -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board29 Nov 2023 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyStatements and editorialsPast in the PresentEN es sl tr ar -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine Salamé23 Feb 2024 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencySonic CommonsPast in the PresentMACBAEN es -

We Have Been Here Forever. Palestinian Poets Write Back

Rana Issa4 Mar 2024 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the PresentEN tr ar -

Indra's Web

Vandana Singh1 Mar 2024 ... and the Earth alongPast in the PresentClimateZRC SAZU -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative Croatia11 Apr 2024 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

One Day, Freedom Will Be

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena Fragnito19 Apr 2024 Art for Radical Ecologies ManifestoTowards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyInstitute of Radical ImaginationClimate -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena Vesić14 May 2024 Past in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa Sonjasdotter28 Jun 2024 The Climate ForumClimatePast in the Present -

Reading list - Summer School: Our Many Easts

Summer School - Our Many Easts6 Sep 2024 Past in the PresentModerna galerija -

Eating clay is not an eating disorder

Zayaan Khan17 Sep 2024 The Climate ForumRecette. Reset. Recipes in and Beyond the InstitutionClimatePast in the Present -

Dispatch: ‘I don't believe in revolution, but sometimes I get in the spirit.’

Megan Hoetger20 Sep 2024 Past in the Present -

Dispatch: Notes on (de)growth from the fragments of Yugoslavia's former alliances

Ava Zevop24 Sep 2024 Past in the Present -

Forget ‘never again’, it’s always already war

Martin Pogačar3 Oct 2024 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Broadcast: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency (for 24 hrs/Palestine)

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board, Rana Issa, L’Internationale Confederation, Vijay Prashad16 Oct 2024 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencySonic Commons -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel Rahman14 Nov 2024 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the PresentClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi Yurteri15 Nov 2024 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Present Present Present. On grounding the Mediateca and Sonotera spaces in Malafo, Guinea-Bissau

Filipa César27 Nov 2024 Past in the Present -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

2024 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the Present -

S is for Silence

Maddalena Fragnito13 Jan 2025 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencySituated OrganizationsEN it -

Milad: The Birth of a Dream and Its Continuation

Sanaa Salameh20 Jan 2025 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the PresentEN ar -

The Library and the Massacre: A Novelist's Testimony on the Destruction of Libraries in the Gaza Strip

Yousri al-Ghoul20 Jan 2025 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the PresentEN ar -

Black Archives: Episode I. Radical Internationalism and Pan-Africanism in the context of the Spanish Civil War

Tania Safura Adam5 Feb 2025 Past in the PresentEN es -

L'Internationale Mission Statement

L’Internationale Confederation10 Feb 2025 Statements and editorialsEN es -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm Hayes14 Feb 2025 Past in the Present -

A Date Palm Against the Re-Deportation of Parables, or Europe’s Palestine Monument

Robert Yerachmiel Sniderman8 Apr 2025 Towards Collective Study in Times of EmergencyPast in the PresentMSNEN pl -

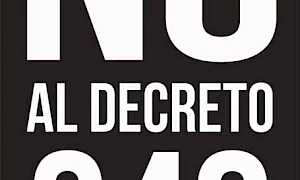

Mass Student Protests in Serbia: The possibility of different social relations

Marijana Cvetković, Vida Knežević31 Mar 2025 Past in the PresentEN rs