From Las Agencias to Enmedio: Two Decades of Art and Social Activism – Part 1

The Big Bang

In November of 1999, only one month before the end of the twentieth century, Seattle happened. It was an event that took everyone by surprise. At the very end of history, a crowd of young people with drums and gas masks managed to entirely disrupt the annual summit of the World Trade Organization. If anyone had told me what would happen, the day before, I wouldn’t have believed that such a thing could happen; not in a world that seemed to have stopped spinning. At that time, the world was like a chubby guy sitting on his couch, grinning contentedly, munching on cupcakes and singing to himself: ‘Yo soy así, y así seguiré. Nunca cambiaré.’1 And suddenly, the images of those kids sitting in the middle of the road and shouting ‘Another world is possible!’ came popping up on everyone’s screens all at once. The effect was like a magic potion: it broke the spell that had kept us young-but-frozen.

When it happened, we had already been enduring neoliberal globalisation policies for at least a couple of decades. Much of the social welfare system we knew was being dismantled. There was a deliberate massification of precarious work, and widespread indebtedness in the form of student loans and home mortgages. These were times in which everything took on the form of a company: governments, institutions and, little by little, even people became something akin to companies of their own, driven solely by the search for economic gain. It was in this world, a world seen solely as a set of profitable opportunities, that, amid the total capitalisation of life, the Seattle images burst through.

It was those boys and girls, standing arm in arm at the gates of the building where the World Trade Organization summit was to take place, and those Robocop cops, who pepper-sprayed them in the face, that brought politics and social activism back into the limelight. Suddenly, everyone wanted to be part of this new thing that had just emerged, including, of course, contemporary art museums. If a medieval art museum becomes outdated and ceases to keep up with current events, that’s fine; it is a medieval museum, after all. If the same thing happens to a contemporary art museum, it automatically ceases to be contemporary; and that is a big problem. Thus, just a few months after the Seattle events, the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA) contacted La Fiambrera Obrera (The Worker’s Lunchbox) to coordinate a talk on art and new social movements, ‘like those in Seattle’.

La Fiambrera Obrera was a group of four artists: Santi Barber, Curro Aix, Xelo Bosch and Jordi Claramonte, who, during the second half of the 1990s, had carried out a number of political performances and urban interventions, seeking by all means to give these aesthetic experiments some kind of social effectiveness. What MACBA proposed to them was more or less what all museums usually offer: to organise a two-or-three-day seminar in which a handful of international speakers would talk about the new political landscape that seemed to be opening up after the Seattle demonstrations, and its relationship with the arts.

Santi, Curro and Xelo would have liked to accept the proposal but were unable to, for personal reasons. But Jordi did accept, with a couple of conditions: first, that the guest speakers should remain in Barcelona a little longer and be given a space in which to develop and share any ideas emerging from the experience of the workshop with attendees; second, that the workshop be free and open to everyone wishing to attend. After some costly negotiations with the museum’s staff, Jordi finally got his way.

And that is where I came in the picture, along with a few other persons: persons such as Marta Trigo (also known as Titi), whose work and dedication would be essential to developing some of the projects we were about to embark on; or Pere Albiac, a very young photographer who had taken part in demonstrations against the IMF and the World Bank in Prague and whose life was completely shaken up by it; or Mar Centenera, a journalism student who sought to write about current issues and get involved in them in a way different than the detached and dispassionate one she had learned at college; or Josian Llorente (aka Josianito) and Maite Fernández (aka Cacharrito), a couple who had just arrived from San Sebastián and were eager to do lots of things. Cacharrito was an artist but she was also a great producer, and Josian, who studied architecture and design, soon became the group’s techie. Ona Bros and José Colón also popped up around that time, determined from the start to do something connected to what they did best: photography. There was also Marcelo Expósito, an artist who was well acquainted with MACBA’s management and who, from the very beginning, acted as a mediator between us and the museum.

Direct Action as a Fine Art

Despite hardly knowing each other, we set about preparing the October workshops, which already by then had been christened ‘De la Acción Directa como una de las Bellas Artes’ (Direct Action as a Fine Art). The space made available to us by MACBA was a building in Joaquín Costa street that was commonly used as a warehouse, quite close to the museum but far enough that we could maintain a certain autonomy. We called it El Cuartelillo (the Small Barracks), and it was at full capacity from the very day they gave us the keys and we moved in.

It was there, during the weeks prior to the workshops, that we first came into contact with many of the social collectives with whom we would later develop a good number of projects. It was also there that we designed the first campaigns, the first posters, the first websites… and that, amid all that activity, we came up with the name of Las Agencias (The Agencies). If I remember correctly, the name first came to Javier Ruiz, a guy from Malaga who had been living in London for several years and was, at that time, very much involved with the Reclaim the Streets movement. Given the amount of graphic materials we had produced in such a short period of time, he thought it would be a good idea to build that into a permanent structure, ‘something like a graphic design agency for social movements’. We found the idea as amusing as the name he proposed for it, Las Agencias: a good name is always one that lends itself to different interpretations, and Las Agencias did just that. I, for example, always associated it with the idea of taking as much as we could before the museum kicked us out on the street, something I was sure would happen sooner rather than later (as was indeed the case).

When the day finally came to open the workshops, we decided to change their location. Instead of holding them at MACBA as planned, we moved them to Espai Obert, a community centre that was very popular with Barcelona’s social movements at the time. The change of location was mainly due to some social collectives’ refusal to set foot in the museum. They claimed it had been the direct cause of the gentrification of the Raval neighbourhood since its (MACBA’s) inauguration, and, to be honest, they were right.

Las Agencias Logo (author: Las Agencias, 2000).

It was a couple of days filled with introductions. We were visited by representatives from®™ark, Ne Pas Plier, Reclaim the Streets, Kein Mensch ist illegal and other international collectives that are, or were then, halfway between art and social activism. The workshops were a great success and received wide media coverage. The museum’s management was delighted and immediately expressed interest in continuing the project. They asked us how we intended to continue with everything we had just set in motion. We answered that we would do so by means of a ‘continuous intervention device’ called Las Agencias, and proposed we keep using El Cuartelillo until June, turning it into a ‘symbolic production centre’. We planned to go on working until then because, during the course of the workshops, we found out that the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) had decided to hold their next meeting in Barcelona in early June, and we intended to give them the welcome they deserved. The museum agreed and gave us twelve million pesetas (approximately 72,000 euros) to carry out our plan. We had never seen such an amount of money before, nor have we ever seen it since.

Las Agencias and contemporary art

Today it is pretty much taken for granted that truly contemporary art must be imbued with its social context, and that artists are not so much individual producers of objects, but persons who collaborate with and create specific scenarios. But things were not like that when we started working as Las Agencias, far from it.

Held in 1997, documenta X spawned a renewed interest in the social and political orientation of art. In its announcements, it extolled political philosophy and sociology as the new interdisciplinary frameworks for contemporary art. However, none of the collective and activist practices that had begun to emerge in Europe (the ones we were interested in) were included in that exhibition. The works exhibited at documenta X were mostly installations, presented to people with the clear intention of finally bridging the eternal gap between art and life; but they only served to further emphasise the gap they sought to abolish.

It was at that time that a very particular term first became widely used: ‘project’. A project was then any work that understood art as an open process rather than as a finite object. The term rapidly came to refer to almost any artistic practice which sought to endure over time and somehow engaged in a dialogue with social issues. Most site-specific and relational aesthetics projects (both very much in vogue at the time) are good examples of ‘projects’.

At first glance, a relational art installation might seem to offer the chance to live a real social experience within it, as if the long-cherished avant-garde dream of erasing the stubborn separation between art and life was here fulfilled. However, this was not the case. As soon as one approached these installations it became clear that putting them to any practical, potential use, beyond their status as art, was completely out of the question; and that made the spectator feel utterly rejected and let down.

Almost all the art on the official exhibition circuits at the time was marked in some way by this impossibility of its being used. We saw much of that art as like the sociologist who is never present in the world that they describe. It is true that it was no longer so focused on objects as before, but the only thing it did with the relationships and situations in which it now took an interest was to tear them away from everything that tied them to the actual world and trap them in a sphere of pure appearance.

We, in turn, set out to develop a series of formal and collective experiments aimed at opening up the forms of life that we wanted to experience. Among other things, we wanted to promote the surreptitious forms of dispersed, tactical and artisanal creativity of anonymous people. More than the autonomy of art, what really interested us was our own autonomy: the autonomy we had to interact with art however we pleased.

In addition to our constant endeavour to experience collective art, our work was always a relentless attempt to apply art to specific situations in our lives. Something like what Stone Age humans did, when they drew a moose with the same hands they had just used to hunt it.

Las Agencias and social activism

On the other hand, social activism was not much better than art. When we started meeting with all those social organisations in Barcelona, we found a pretty bleak picture. Many of the so-called social movements of the time were still trying to fill the vacuum left by the defeat of the labour movement, of which they were, in a manner of speaking, downsized versions, and they insisted on organisational forms that seemed empty to us. The murmur of a monotonous voice moved heavily through every one of their endless assemblies; an ideological element still prevailed in their speeches. Their gaze was fixed on the past, as if they were afraid of waking up to the world in which we really lived.

Las Agencias was not driven by ideology; we believed all ideologies had long since collapsed. We had no great certainties or clear alternatives, nor, of course, did we have a good, militant discipline. We never set ourselves any maximalist goals, we never intended to do away with capitalism or consumerism. We were of the opinion that aiming for such an ambitious horizon would bring us nothing but frustration and would limit our ability to perceive what was really happening around us, in our daily lives, where it was indeed possible to change things.

We sensed that there were many forces awaiting deep within us; forces capable of manifesting themselves anywhere and in any situation, changing our lives completely. All we had to do was find them and represent them, bring them into our imagination as soon as possible. That is why we bet on art, because every activity performed by an artist, by a good artist, has always consisted in finding those forces that increase chaos, showing that every society is in a permanent state change.

The Las Agencias method

The Christmas holidays were not yet over and we were already working at El Cuartelillo every day. In a very short time, El Cuartelillo became the organisational nerve centre of the demonstrations against the World Bank and the IMF. New ‘agents’ joined at that time, including Domi; a very active guy, committed to some social projects that were taking place in L’Hospitalet. His work was essential for the transformation of the bus that we acquired, and for many other things as well. We were also joined by Oriol, a very experienced web designer who gave a major boost to our online image. At that time I called Miguel Angel (aka Amonal) to join the team. Amonal was an old friend of mine from Zaragoza, from the times of La Insumisión (the Insubordinate Movement),2 squatters’ social centres and punk rock. He already had a lot of experience working as a graphic designer. He had designed many of the graphic campaigns that came out of alternative community centres during the second half of the 1990s, and without him, we could hardly have developed and produced the extensive number of graphic materials we were able to in the short time Las Agencias was active.

Aviv and Oriana also joined Las Agencias at that time. Aviv was an Israeli who had studied art in Chicago. There, he had published an underground magazine focused on experimental design and created some floatation suits for migrants who risked their lives crossing the seas by boat. Oriana Eliçabe was an Argentine documentary photographer who had spent the last six years living in Chiapas to record the daily lives of the Zapatistas. As soon as she joined the group, she started working with José, Ona and Pere and our photographic work took a giant leap forward.

Oriana was not the only Argentine addition. Erika Zwiener also joined the group around that time. A graphic designer, she immediately began to collaborate with Oriol and Amonal in the development of aesthetic proposals. Then came Nuria Vila, a young woman who had recently received her degree in journalism and who originally approached El Cuartelillo to write an article on Las Agencias, but was so touched by everything that was happening there that she soon put her camera and her notebook away and dove headlong into our work. One of our last additions was Ales Mones. Ales was born in the city of Gijón, in Asturias, and even though he never specialised in anything in particular he was good at everything, from taking quality photos to sewing a suit, cooking for a crowd or setting up a rave with hardly any resources.

In addition to all the people already mentioned, who were the main group of agents, there were many others who participated very actively in the creation of Las Agencias. Most of them came from Barcelona’s social collectives and movements, and headquartered themselves at El Cuartelillo as the date of the June summit approached. Among them were, for example, Arnau Remenat, Mayo Fuster, Tupa Rangel and also Enric Durán, who shortly thereafter would be wanted by the police for taking out a series of bank loans, investing the money in different social causes and never paying any of it back. I could also mention Ada Colau, a young woman who, after dabbling as an actress in a local series, switched from playwriting to social activism. A few years later, she would become the first female mayor of Barcelona.

At some point, Las Agencias was divided into five agencies: the Graphic Agency, the Media Agency, the Fashion and Accessories Agency, the Photography Agency and the Space Agency. All of them applied the same working method: collective creation workshops. These workshops were spaces that allowed participants to come into contact with each other, where each contributed what they knew best, combining their work with others’ until they were able to create something together, yet without ever losing their individuality. ‘Merged individualities’ could be a good description of what those collective creation workshops were. All of the work we did at that time was created using this method, from our public actions and interventions to the texts we wrote together. One could say that the general result of this pooling of diversity, constructing shared patterns, images and ideals, was the development of creative methods of action that also helped us deal with problems we faced in our daily lives.

Show Bus

The first decision we made as Las Agencias was that none of us would get a céntimo of the twelve million pesetas that MACBA had given us. It was a risky decision, because none of us had a guaranteed income at the time, except for Jordi, who had received a doctoral scholarship. Even so, I believe it was the right decision. Setting personal finances aside and allocating all the money to the projects we were beginning to develop allowed us to work free of any influence that could have come with getting paid. I remember that the first thing we did with the money was to buy a bus. We found out that someone in a small town in the Basque Country needed urgently to get rid of a very old one, and was selling it very cheap. So, a couple of agents went out there and drove it back to MACBA in just one day (and without a bus-driving licence).

The idea was to transform the bus into a ‘spatial intervention device’. Our thesis was that, in recent decades, our cities had become increasingly alien territory. The social life of neighbourhoods had been drastically displaced, and the historic city centres had undergone a ‘museumification’ process aimed at extracting as much profit from them as possible. Across the board, economic forces had occupied cities, progressively making urban life more difficult; hence the need to equip ourselves with a mobile device in order to face the hostile terrain without the need to establish a permanent headquarters.

Show Bus (author: Las Agencias, 2001).

Our goal with the Show Bus, as we called this project, was to develop a series of intervention tactics. These were mobile tactics, capable of eluding the mandates imposed on urban spaces, allowing us to use them in unpredictable ways. And precisely because they were in constant movement, they would not be easy to locate and so suppress.

The first thing we did when we got our hands on the bus was to change its colour. We painted it orange with yellow polka dots so it would never go unnoticed. We also built a wooden stage with a powerful sound system over its entire roof. This minimal infrastructure allowed us to stage all kinds of events and performances, from concerts, parties and plays to lectures, public talks and debates. The side and rear windows were turned into screens on which we projected all kinds of images. With the Show Bus thus equipped, we managed to turn a lot of squares and streets throughout Spain into improvised open-air cinemas. The inside of the bus was also completely modified to meet all of the technical and logistical requirements of our public interventions. We replaced the rows of seats with work tables and even installed wi-fi, which was no easy feat at that time.

For about two years, a large number of collectives and social organisations used the Show Bus. It soon became an essential tool for the implementation of a number of different actions, increasing their visibility and effectiveness in a remarkable way. Direct action on wheels, that’s what the Show Bus was.

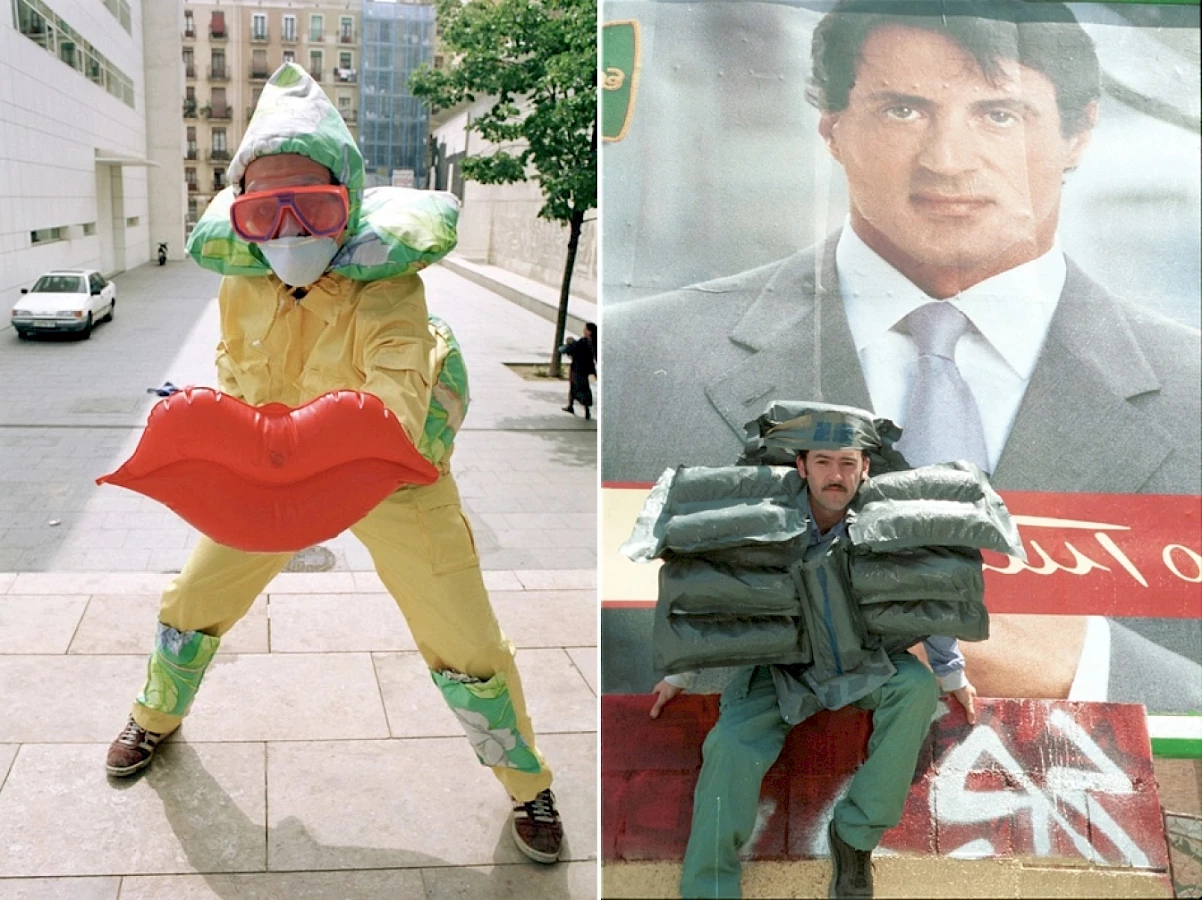

Prêt-à-Révolter

Our second investment of the MACBA money consisted in the purchase of a few hundred metres of brightly-coloured fabrics and a couple of large sewing machines. We wanted to make unisex suits that would serve two different purposes. On the one hand, the suits were intended to protect the wearers during demonstrations or any other event in which they could suffer bodily injuries. On the other hand, our costumes had to adhere to the precepts of what we then called ‘direct representation’: that is, our own autonomous ability to represent our way of life. We did not like the way social activism was represented in the media at all; journalists at the time had begun to introduce the term ‘black bloc’ to describe the anti-globalisation movement. This term reduced a series of rich, complex and diverse social experiences to an image of black-clad, hooded, mindless youths engaged in the arduous task of stone-pelting the cities they passed through. So we set out to synthesise all the richness and diversity that the media left out of the representation of the anti-globalisation movement through, and into, fashion design.

We called this project Prêt-à-Révolter because we wanted to change revolts in the same way prêt-à-porter changed fashion. In a way, prêt-à-porter meant the massification of fashion, its ‘democratisation’, so to speak. Our collection sought to achieve something similar with revolt and social activism: to democratise them into mass phenomena. Since fashion can create a feeling of group belonging, granting a certain ‘autonomy’ to define the aesthetic and creative dynamics that a group presents on the social stage, this was another of our design goals. We sought to imprint social meaning on the jackets, trousers and accessories we made for demonstrators, with the intention of turning them into a communication channel; a sort of symbolic transmitter capable of representing and disseminating the cultural conditions underlying social activism.

"Prêt a Revolter" (author: Las Agencias, 2001).

We designed and produced Prêt-à-Révolter over a number of workshops held in Barcelona, Madrid and Zaragoza. They were basically civil disobedience workshops in which, together with a number of collectives and social networks, we analysed the tactics deployed by both the police and activists during demonstrations. Then, we tried to respond to them in the form of fashion and equipment design. We worked hard to ensure that our designs could be appropriated by anyone who needed them, so that the users themselves could transform and adapt them to their own needs in a specific context. Also in the workshops, we focused on the creation and strengthening of what we called ‘affinity groups’. It was always very important to us that, as the future wearers of Prêt-à-Révolter, the people who passed through our workshops should be involved in both the design and the making of these garments. Thus, once the workshops ended, they would be able not only to wear, but also to export the work to other places, thus eventually creating new Prêt-à-Révolter design groups.

Prêt-à-Révolter was a bid to renew the appearance of social activism, an exercise in ‘self-representation’ that sought to break down the walls of the old watertight compartments in which some forms of activism were trapped. In short, we could say that Prêt-à-Révolter was a response to the practical needs of the civilly disobedient, in the form of clothes. The work we did with different activist collectives and networks resulted in two full Prêt-à-Révolter collections: ‘Basic’ and ‘Garbage Sports’.

The ‘Basic’ collection equipped protestors with accessories essential to adequately protecting the most sensitive areas of their bodies. These incorporated defensive design-components such as the fun airbags we installed in the sleeves of jackets, or the micro-cameras we added to certain garments, allowing users to live-broadcast any situation in which they found themselves.

The ‘Garbage Sports’ collection was designed for wear in high-risk situations, those that tended to be much more violent confrontations. The suits in this collection were entirely made out of recycled materials, mainly plastic bottles and garbage bags; hence the name. We filled the plastic bottles with compressed air so that they could withstand very high-pressure impacts, such as when resisting a police charge in the front line.

Like any other fashion brand, Prêt-à-Révolter represented a symbolic force that sought to answer a series of structural social changes that, in our opinion, were taking place. Changes linked to the expansion of the economic crisis to more and more sectors of the population necessitated the broadening of the field, and the imaginary, of social protest. We had to start preparing people for revolt, and that is literally what we did with Prêt-à-Révolter.

Artmani

The vulnerability of human bodies in mass demonstrations was something that really worried us at Las Agencias. Prêt-à-Révolter was not the only one of our projects to engage with this issue: Artmani did as well. Artmani was a brand of portable shields. Made of a very light and durable material, they were capable of performing a couple of very important functions (and perhaps more). On the one hand, the shields protected demonstrators from any acts of violence that might occur during demonstrations (police attacks, rubber bullets, etc.). On the other hand (as the brand name indicates), the Artmani shields comprised an art exhibit designed to be displayed at demonstrations. The ensemble of photographs pasted onto their surfaces was intended to attract the gaze of all those present. And, indeed, the visual created by the demonstrators’ bodies behind those large shield-mounted photographs was utterly irresistible for the photojournalists. The shields made it into the newspapers countless times.

For us, the representation of an event did not mean its being turned into a mere image but, rather, its being bound, or the binding of it to, a new meaning. The media irruption of those images, so different from the ones we were used to seeing, somehow inaugurated a new imaginary of social protest: a new way of interpreting and feeling it. Like Prêt-à-Révolter, Artmani was another practical way of sneaking new and unpredictable interpretations of social activists and their actions into the media; another way that we found to confront the world, using images as a shield.

Free Money

During our time as Las Agencias, we also developed a good number of graphic campaigns in collaboration with collectives and social movements from all over Spain. These include the anti-war campaign ‘Guerra Mítica’ (Mythical War), as well as campaigns against property speculation and the privatisation of urban spaces, like the one we organised around the Reclaim the Streets movement in downtown Barcelona, in June 2001. However, the campaign that was, and that remained, most present in the streets was undoubtedly the ‘Dinero Gratis’ (Free Money) campaign that we developed together with the Oficina 2004 collective, a group of veterans of the autonomy fights of the 1970s together with a few young philosophy students.

Launched in early 2001, the creation process that we developed with Oficina 2004 was a perfect embodiment of that of our workshops. As soon as we started collaborating, all the boundaries that had separated us disappeared as the designers and artists of Las Agencias and the members of Oficina 2004 became as one, dealing with philosophical conceptual and aesthetic considerations in creative unison.

For them, money was the code with which reality was programmed: a reality in which life had been reduced to working, or looking for work. In this context, ‘Dinero Gratis’ was presented as a gesture capable of interrupting this repetitive and excluding code. Together, we were able to translate some of Oficina 2004’s philosophical, economic and anticapitalist critique into a collection of postcards and posters. We also produced a huge number of rolls of adhesive tape with the ‘Dinero Gratis’ logo printed on it. This tape eventually became an essential element of actions undertaken by collectives throughout the city. It was used on so many occasions that it ended up being one of the most influential visual elements of the cycle of protests that began with the World Bank counter-summit in Barcelona. (Our collaboration with Oficina 2004 is ongoing. For all of these years, we have never stopped producing graphic concepts and materials that have been tested in the countless actions we have carried out together.)

Over the winter and spring of 2001, Las Agencias did not stop working for a single second. Activity at El Cuartelillo gradually increased until it became the nerve centre of the demonstrations against the World Bank and the IMF that were to take place in June. We worked at a frenetic pace, spending much more time there than in our precariously rented homes. In fact, I don’t remember spending a single full day at home: I would arrive late at night, lie in bed for a few hours and be back at El Cuartelillo by around 9 a.m. Sharing that intense rhythm with the other agents in Las Agencias brought us closer and closer together. We became friends, and it was that friendship that, among many other things, brought down the barriers that kept the five agencies apart. I remember one day we were holding five simultaneous meetings, something that was very common at the time. We all suddenly stopped, looked each other in the eye and said: ‘Fuck this five-agency thing, one agency is more than enough: Las Agencias, that’s all.’ We laughed, put the tables together and, from that moment on, we all participated in and took responsibility for everything.

La Bolsa o la vida

June was getting closer and closer, and the local media kept broadcasting the many clashes that occurred during the demonstrations against the World Bank. It was on TV, in the newspapers, everywhere. However, less than a month after the demonstrations started, the media still lacked a single shred of evidence to corroborate the story they had been pushing about the activists. They had not a single burning shipping container, nor even a sad broken shop window to photograph, nothing. That was when we came up with the idea of ‘La Bolsa o la vida’ (The Stock Exchange or Your Life).

Josian, who always knew everything, discovered that the Bolsa de Barcelona (Barcelona Stock Exchange) building was classified as a tourist attraction, which meant one could request a guided tour. That triggered our actions. We called and asked for one. A very kind young woman replied that would be no problem, she just needed an estimate of the number of people who would take the tour. We told her about ten thousand people, give or take. As soon as she hung up the phone, the nice young woman did exactly what we wanted her to: she called the police.

"La Bolsa o La Vida" (author: Las Agencias, 2001).

In the meantime, we were busy sending a series of photographs we had taken outside the stock exchange building a few days earlier to the local newspapers. They showed us as an ordinary group of tourists, but with bags (bolsas) on our heads; all very conceptual. The photos were accompanied by a note in which we stated that we were planning to make the most massive group visit to the Bolsa de Barcelona in history, and that all members of the press were invited.

They must have liked the photos very much, because they were published in almost all the newspapers the following day. I suppose they saw in them signs of the altercations that their editors were so insistent upon addressing. The first part of the plan already accomplished, we left the second in the hands of the police. When he saw our photos in the press, the Minister of the Interior of the Government of Catalonia ordered the intensification of the monitoring and control measures that the police had already deployed around the building after our call. More fences, more vans, more police officers: a very complete operation to prevent a visit we did not plan to make.

The only ones affected by these measures were the shareholders and brokers who, accustomed as they were to going in and out of the stock exchange as if they were at home, were very upset at being searched and sniffed by sniffer dogs, over and over again. In fact, they were so annoyed that they unanimously decided to stop going to the stock exchange for a couple of days as a sign of protest. And that is how the stock exchange building was closed for two consecutive days, because of a simple phone call and a few absurd photographs. We threw a huge party to celebrate. Accompanied by the Show Bus, music blaring, hundreds of us spent a whole day dancing frenetically with bags on our heads. We even took a dip in the public fountain on Passeig de Gràcia, just in front of the stock exchange building. If we had to choose between life and the stock exchange, we’d choose life in a heartbeat. Lots of life.

The end of Las Agencias and the return to autonomy

Las Agencias’ collaborative projects (including, among others, the independent news agency Indymedia, which we helped to create, and the bar we opened at MACBA, overlooking the Patio Corominas square, where we fed a lot of people for free for several months) occupied the pages of the press every day during the months leading up to the World Bank and IMF summit in Barcelona. This, together with massive participation in the organisation of events and demonstrations against the summit, forced the World Bank and the IMF to cancel their meeting. It was the first time in history that something like that had happened. We experienced it as a tangible triumph; we celebrated it in style, and we also decided to go ahead anyway with the programme of demonstrations that we had already published.

All our projects had a huge influence on those massive demonstrations. The Show Bus, the Prêt-à-Révolter costumes, the Artmani shields, everything was used by a lot of people those days. At the main demonstration, the police charged hundreds of thousands of people, causing chaos throughout the entire city. Along with a few hundred other people, some of us took refuge at MACBA, and there too the police fired at us with rubber bullets. One of those bullets ricocheted and hit the glass door of the museum. Since then, there have been two great broken glass panes in the history of art: Duchamp’s and ours.

Things got so tense that a delegate of the Government of Catalonia asked for a personal interview with Manolo Borja, the director of MACBA. At that meeting, the delegate expressed her discomfort with our work and warned Manolo that she intended to stop our activities immediately. For a few days, it seemed that Manolo was going to lose his position and that the police were going to seal El Cuartelillo. Some members of Manolo’s technical team were so nervous that they demanded the director expel us, but in the end nothing happened. The museum’s organisational chart remained unchanged, and so did El Cuartelillo. After the demonstrations in June, Manolo Borja called a meeting and proposed that we continue our work for another season, but under very strict conditions. From now on, our working hours would be drastically reduced to fit the museum’s timetable and every new project would have to be submitted to the director for approval. As soon as we left that meeting, it was clear to us that it was over.

Our experience with Las Agencias had shown us that, when political art is not accompanied by a high degree of autonomy, it is just another label; another way of adapting social practices to the institutional logics of the art world and, therefore, to market logics. If, together, we were to respond to both our ways of life and the cultural forms that made them possible, we needed a degree of autonomy on which we were not willing to compromise at all. So, we did not accept the director’s conditions. We packed up our belongings, left the institutional ship and put an end to Las Agencias.

Shortly after our departure, Manolo Borja wrote a rather extensive article in which he presented Las Agencias as an example of what separated MACBA from other international museums. Unlike ‘museum brands’ such as MoMA, museums as spectacle and entertainment like the Guggenheim, or any of all those other institutions that championed a vision of culture built on the basis of biennials and other big events, it was the work of Las Agencias, linked, as it was, to the dynamics and needs of social movements, that, in the director’s words, made MACBA a living museum, one that was fully active in society. A few months after this piece was published, Manolo also left MACBA, moved to Madrid and took office as the director of the Reina Sofía museum.

Jordi also returned to Madrid. There, he started a new phase with David (aka Tina Paterson), an old friend of his who had visited El Cuartelillo a few times. Together, the two of them carried out the campaigns ‘Mundos Soñados’ (Dreamed Worlds) and ‘Sabotaje Contra el Capital Pasándotelo Pipa (SCCPP)’ (Sabotaging Capital While Having a Blast). We tried to continue working together for a while, them from Madrid and us from Barcelona, but it did not work out and we soon lost contact for good. A group of about fifteen of us remained in Barcelona, alongside the many others with whom we continued to collaborate on a regular basis. We found a new work space, a very large flat in the Gràcia neighbourhood that had been used by social movements for years. We used it to store our personal belongings and all the materials we had produced as Las Agencias, then immediately left for Genoa to take part in the international protests against the G8 summit, dressed in our Prêt-à-Révolter summer collection.