From Las Agencias to Enmedio: Two Decades of Art and Social Activism – Part 2

Genoa, our turning point

The G8 counter-summit in Genoa was the high point of the anti-globalisation movement. It was held in July 2001, at a time when the IMF and the World Bank were experiencing serious difficulties to meet and hold their summits. Social demonstrations against neoliberal globalisation were on the rise, and so was police violence. Gothenburg saw the first bullet wound and Genoa saw the first death. Carlo Giuliani, a young man of 23, lost his life a few metres away from where we stood, shot by a police officer. That traumatic event and everything else we experienced during those days in Genoa was a major turning point in our work.

The argument behind the excessive police repression was based on a myth created by the media: the myth of the black bloc. The media created a very particular image of this political group, presenting it as a criminal organisation solely responsible for the violence experienced in the anti-globalisation demonstrations. In the hands of the media, the black bloc became the new enemy: the enemy of financial power; of those citizens who reject violence, and also the enemy of the anti-globalisation movement itself, as a line was drawn between violent and non-violent demonstrators. This simplistic media representation, based on the friend/foe schema, severely downplayed the rich diversity of the global movement.

New Kids on the Black Block

For this reason, we decided we must urgently set out to effectively and systematically erode the term black bloc itself and, as soon as we returned to Barcelona, we got down to work. To achieve this, we resurfaced an idea that we had already begun to toy with during the last period of Las Agencias: New Kids on the Black Block. The name was a mix between black bloc and New Kids on the Block, a band that was very commercially successful in the late 1980s and early 1990s. New Kids on the Block, or their record company, had developed a formula that would later be repeated and perfected with countless other bands, including the Backstreet Boys and the Spice Girls: five young people, each with a diverse aesthetic and easily recognisable to the teenage public, performing the catchiest songs. Behind each of these groups was a perfect formula, developed by a record company for clearly commercial purposes.

New Kids on the Black Block Logo (author: Las Agencias, 2001).

But far from criticising either the band or the black bloc movement, with New Kids on the Black Block our intention was to highlight the logic of communication that imbedded both groups into a logic of consumption. By showing the very mechanisms that led to the development of the anti-globalisation movement, we aimed to attack, and denounce, its criminalisation. We did this by appropriating the forms and language of a group of fans, producing stickers, posters, fanzines and pins. We also wrote songs, produced the odd video-clip and created a lot of fashion designs to be used in the activities that would be carried out by New Kids on the Black Block in many cities around the world.

New Kids on the Black Block at the burned Show Bus.

New Kids on the Black Block soon became a tool for political transgression, devoted to unveiling, in our performances, the mechanisms employed by dominant discourses. By appropriating those discourses and shattering them from within, we opened up space for more diverse and complex representations. We performed in the streets, amid riots or on television sets. We gave countless press conferences on behalf of the anti-globalisation movement. But no one ever knew who was hiding behind that name. New Kids on the Black Block was always conceived as a ‘multiple identity’, a sort of collective and anonymous mask. New Kids on the Black Block gave to anyone who needed it, who stood up against the reductionist and criminalising narratives that ran so strongly in the media, a power to express and represent themselves.

We presented New Kids on the Black Block to the public in style. The European Union had just granted the six-month presidency to Spain and a campaign called ‘Against the Europe of capital, globalisation and war’ had been launched by many grassroots organisations across the country to protest each of the summits scheduled throughout the presidency. We intended for our Show Bus to be one of the main players in these protests. Our idea was to travel around the country offering it to many social movements as a communicative tool and an intervention device, but it was impossible: one day before the demonstrations began in Barcelona, we found the Show Bus completely destroyed.

New Kids on the Black Block Logo (author: Las Agencias, 2001).

Someone had broken into it at night and smashed the work tables, the screens and the driver’s cabin. They had then climbed onto the roof and smashed the stage. Finally, they had doused it with gasoline and set it on fire. The news caught us completely off guard. We did not know what to say or what to do. None of the usual responses to this kind of incident would satisfy us at all. We could not see ourselves grieving our loss before the press, or demanding an eye for an eye. So, after giving the matter some thought, we decided to take advantage of this incident, turning the crisis into an opportunity to present New Kids on the Black Block to the public at large.

We put on our costumes, took some funny pictures in the burnt-out bus and sent them to the press, with a note saying: ‘We are the New Kids on the Black Block, a group so radical that we burnt our own bus.’ It worked like a charm. In just a few hours, everyone knew about New Kids on the Black Block. That is how, in a very short period of time, this new collective identity gained entry into the myth-making machine, and had hundreds of fans unconditionally join its cause.

During our time as New Kids on the Black Block, we tested a series of creative strategies that successfully combatted both media criminalisation and police repression on countless occasions, always with a lot of humour.

However, the violent repression of the anti-globalisation movement was on the rise, and we could not get Genoa out of our minds. So, all throughout the ‘Another World Tour Is Possible’ world tour, we kept thinking about a new intervention model. We wanted to go on fighting the power of multinational companies and the (increasingly intrusive) spirit of neoliberalism, but now we wanted to do it in everyday life, without relying on big events or mass demonstrations. We were convinced that there had to be something people did on a daily basis which, in some way, was already a threat to capitalist globalisation, however small. We searched everywhere until, finally, one day, we found something: stealing. This habit, ingrained in thousands of people, cost multinational companies millions of dollars in losses. Stealing was a kind of invisible guerrilla warfare, waged daily in shopping malls around the world. We created the Yomango (Yo mango, I steal) brand to make this war visible.

Yomango Logo (author: Yomango, 2002).

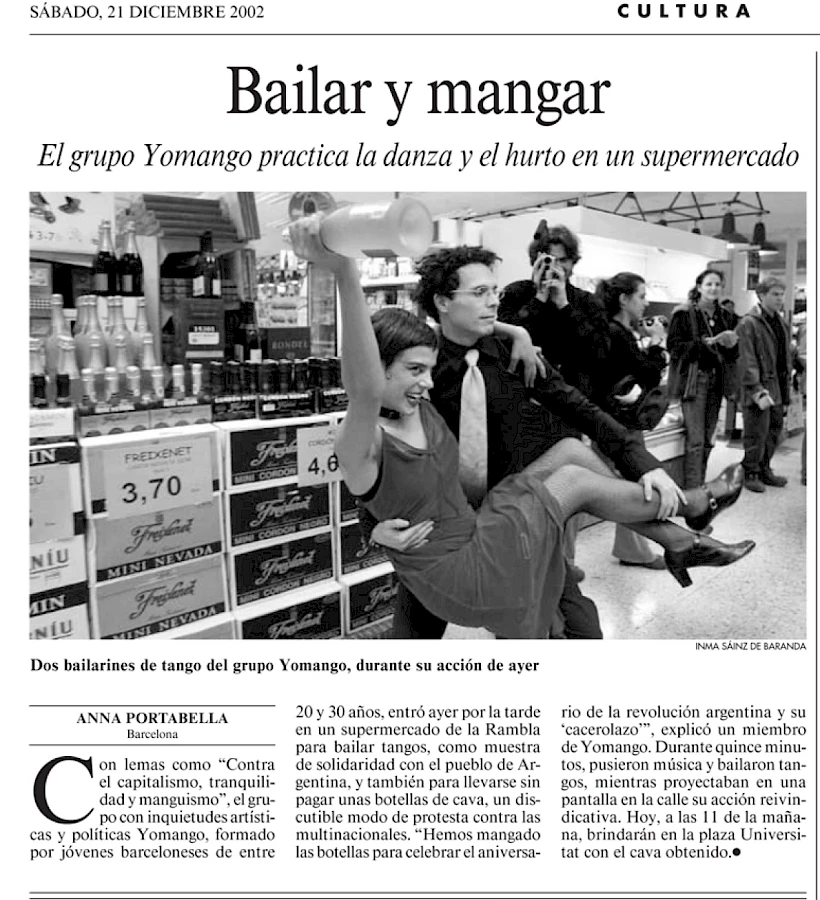

Public presentation of the Yomango brand (author: Yomango, 2002).

Yomango

I remember the name came to me in bed. I had just turned off the light when suddenly ‘Yomango’ resounded in my head like thunder. I sat up, turned on the light on my bedside table and wrote it down in my notebook. Right next to it, I wrote a short comment: ‘A brand that steals everything from other brands’. Then I turned off the light and went back to sleep. Over the next two days, I locked myself in at home and continued working on the idea. I took a lot of notes and drew some sketches. On Thursday night, we all met for dinner at Oriana’s house and, once we had finished, I presented the idea to the group. The reception was spectacular! You could tell it was something that was on everyone’s minds. By the next day we were already working to develop this brand and its lifestyle.

Yomango was, from the very beginning, an attempt to redirect marketing and all of its social-intervention techniques in pursuit of a human essence, self-defined, and so capable of self-definition, beyond the economic sphere. We started from the premise that the commercial impulse by which our lives were being driven was the sign of a very sad passion for them to be ruled by. We felt that all the happiness represented every day in advertising concealed an ocean of sadness and dissatisfaction. In a way, Yomango was our answer to that reality. Our goal in creating that brand was to go out and test our chances of intervening in any way in an imaginary that was dragging us all, with increasing energy, towards a very limited existence: that of consumers. Yomango was the vehicle in which we set out to explore the contours of true enjoyment.

We set ourselves a challenge: Yomango would never create anything, it would only steal. We sensed and so we decided that, in order to establish a subversive relationship with consumption and its representations, we had but to combine the elements that were already present in the consumption imaginary in a different way. What we found was that reconstructing the painful truths hidden behind consumer goods and their advertisements resulted in an endless number of scenarios that brought great enjoyment, both individually and collectively. No surprise, then, that one of the slogans we used the most in the early days of the brand was this one that we stole from MasterCard: ‘Yomango, because happiness cannot be bought.’

Among the first things we did once we had our logo and website ready were the Yomango dinners. These were weekly meetings where a bunch of people shared everything they had stolen during the week. The fact that we could not know the menu in advance made those dinners very spontaneous and improvised events. They soon became a point of reference in Barcelona. It was also around that time that we installed an open publication module on our website, something like a small Facebook wall but anonymous and free. Both the dinners and the online forum immediately created a community of people who, over several years, formed a structure for the exchange of knowledge, practices and experiences that was very enriching for the whole Yomango brand and lifestyle. From those two spaces were spawned, for example, many of the ideas that the fashion department would later realise. The first songs and many of the images that represented the brand’s first seasons were created there.

The high level of engagement created by Yomango showed with absolute clarity that the brand made visible and appealed to something that was very widespread in society, but had been almost invisible until then. In order to provide outlets for all of that activity, we created a series of departments: the art and design department, the fashion and accessories department, the R&D department and, of course, the stealing department. Since we still had no money, some of us signed up to work nights in the stores of some of the biggest multinational clothing companies, such as Zara and H&M. It was there that we carried out all of the tests, with frequency inhibitors and other materials, that we then applied to Yomango fashion and performance. The social network and lifestyle that Yomango eventually became somehow began to take shape on those endless nights that we spent locked in those huge dark stores, unloading boxes of clothes from the company’s trucks and hanging thousands of garments on their corresponding hangers.

Yomango-Tango (author: Yomango, 2003).

Yomango-Tango (author: Yomango, 2003).

On 5 July 2002, we presented our brand to the public. We had received an invitation to participate in an exhibition at the CCCB (Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona), and we decided to take advantage of the opportunity to make the brand public. The event in question took place in a branch of Bershka on Portal de l’Angel street, Barcelona, in the middle of the sales season. The street was buzzing with people when Yomango performed its unique magic trick. A size 34 blue dress with a retro belt and a butterfly printed on its bodice disappeared before everyone’s eyes and turned into a real work of art that, a few hours later, appeared on display in the museum. All the local newspapers echoed with the event: ‘Anti-system group claims theft is a new art style’, ‘Stealing from multinationals, the latest trend in art’. The force of that intervention was such that it shook even the mayor, who felt he had to visit the CCCB to make it very clear to the director, in our presence, that ‘art is meant to conceal problems, not create them.’

That intervention was followed by many others. Over a very short period of time, Yomango spread everywhere like a rumour. Museums and social centres worldwide took an interest in this strange brand that fed off everything it stole from other brands that crossed its path. In Madrid, Jordi and David began to put the brand in the spotlight. They published a couple of Yomango booklets that had huge repercussions: El libro rojo (The Red Book) and El libro morado (The Purple Book). They also organised freestyle sessions ‘sponsored’ by the brand. In Barcelona, we increased the number of collaborators: Bani Brusadin and Flo became part of the group around that time. We went on tour, we visited many countries and we opened a new Yomango branch in each of them. In less than a year, we managed to get the stealing department to coordinate brand activities on more than one continent: in Mexico, Italy, Germany, Argentina, Chile… Before we knew it, Yomango had become another multinational; the only multinational brand that was outside the market. In record time, our brand became a symbol of resistance against neoliberal globalisation, and it did so by stealing the language and appearance of multinational companies (and, of course, some other things as well).

Like any other form of art, Yomango had the gestural capacity to establish unpredictable relations with reality and, therefore, to redefine it. Our performances in shopping malls, the fashion designs, the catalogues; all served the purpose of translating the symbolic meanings that operate in consumption, bridging each person’s individual history with the larger stories, or narratives, that make up consumerism. If the representations in advertisement deny people’s spontaneity, creativity and capacity to transform their surroundings, our artistic interventions did the opposite. They sought to recover our power to act on the world; to change it. They were, so to speak, an attempt to establish a different relationship with the space and time of consumption as already deployed in almost all aspects of our lives.

Yomango developed an interventionist art, capable of crossing on numerous occasions the sharp threshold that leads to enjoyment; this being precisely the relationship that Yomango invited us to develop with our existence. With Yomango, we learned that we are actually governed by our environment (visual, architectural, urban…), which may seem at first glance to encompass everything, but is actually full of holes. These holes are not visible at first sight, because ‘seeing’ has meant settling for what we can see. Yomango taught us that the holes exist only to the extent that we bring them into existence, and that it is only in this way, by bringing that which cannot be seen with the naked eye into existence, that we can create a new relationship with everything that surrounds us. In fact, Yomango’s actions were just that: vanishing points capable of interrupting the time and space of consumption. Our insistence on sketching out those points was what ultimately created a ‘place’ (the brand itself) that was half imaginary and half physical: a place where many persons were able to establish a different relationship with consumption. It was precisely there, in that unexpected place, that this entire international community settled and its lifestyle was affirmed. Sometimes you call out to life with the right words and life comes. We called out ‘Yomango’ and life came.

A nameless force

Yomango kept us busy for a few years. Its massive activity and the influence it had on so many different people and places changed the way we worked and the way we understood social and political issues. All those actions carried out by anonymous people, all those authorless gestures capable of transforming endless adverse scenarios into enjoyment without the need to rely on the classic levers of political action were, for us, an omen of what was yet to come. From 2004 onwards, we began to witness a series of political expressions that no longer answered to what we used to understand as ‘social movements’. They were presences that appeared in the public sphere and had no possible political representation whatsoever, collective expressions in which the existential and the political appeared indivisibly intertwined. They were, like Yomango, unexpected subjective spaces that had room for anyone; spaces capable of interrupting the social workings that create the map of what is possible. Since they had no name, we referred to them as the ‘nameless forces’, and we immediately became very interested in them.

The first time we saw one of these nameless forces was after the attacks at the Atocha train station on 11 March 2004. The spontaneous social response that flooded the streets of Spain in a few hours left us dumbfounded. When faced with the horror of the attack, people’s lives seemed to cling together to face it. This unexpected connection created a most inclusive and multiple social space, a space that was characterised by its lack of representation: nobody ordered it; it was not endorsed by any organisation, the call was spread through SMSs and the internet alone. The meeting was not attended in blocks; no one knew who was standing next to them. It was a very diverse event. For once, things did not spawn from a previously constructed meaning, but developed on the go. Great creativity unfolded during the brief time it lasted: thousands of new slogans were born on anonymous and personal banners, loaded with great intimate expressiveness. Its atypical social expression turned everything upside down and disappeared as quickly as it had developed.

V de vivienda

The second nameless force appeared with V de vivienda (V for vivienda, that is, dwelling, living place). It was 2006, the year more houses were built in Spain than in France, Italy and Germany combined. This caused the largest economic bubble in the history of our country: the real-estate bubble. It was the time when banks offered forty-year mortgages to anyone who came to their offices. Forty years of your life paying for a place to live! The situation was totally unsustainable (very similar to the current one, by the way) and that unsustainability soon took the form of an anonymous email that jumped like a hare across the internet, from inbox to inbox. The email was brief, it said only this: ‘For the end of real-estate speculation and the right to decent housing, next Sunday sit-in at all Spanish squares.’ Once again, an anonymous voice expressing a pain and unease shared by many. The only difference between this and the demonstration against the Atocha attacks was that this new, nameless force did not disappear so quickly.

The first sit-in was a resounding success. Thousands of people answered the call by taking to the squares of the main Spanish cities. All of us who attended experienced the joy that comes with being moved by the power of being together. The operation was repeated the following Sunday and a few more Sundays thereafter. This series of anonymous calls began to form a kind of spontaneous movement. For the first time, an anonymous and massive force aspired to survive over time, and that brought with it the problem of visibility.

In a way, the movement for decent housing appeared by hiding. It chose as its name ‘V de vivienda’, a joke, a wordplay on the title of the comic and film V for Vendetta. This choice was guided by the explicit desire not to be named, represented or even identified. ‘V de vivienda’ actually meant nothing, and it was precisely because of this, because it was nothing, that everyone could fit inside it. It was from this inclusive and non-identifying capacity that it drew its force, its nameless force. But once the movement tried to survive over time, things got hard, and V de vivienda was immediately forced to adopt a concrete visual identity, easily recognisable by the media, if it wanted to maintain the quota of visibility it had unexpectedly gained with its irruption into the public eye.

We had some experience with the problems that come with visibility. Both Las Agencias and Yomango had taught us a few things about it, so we decided to take matters into our own hands. If we had to define ourselves and adopt an image in order to retain our presence in the media, we would find one that would wear down the strength we derived from not having a name as little as possible. We set to work. It wasn’t easy: finding a common imaginary among those gatherings of people who were so different from each other was not easy at all.

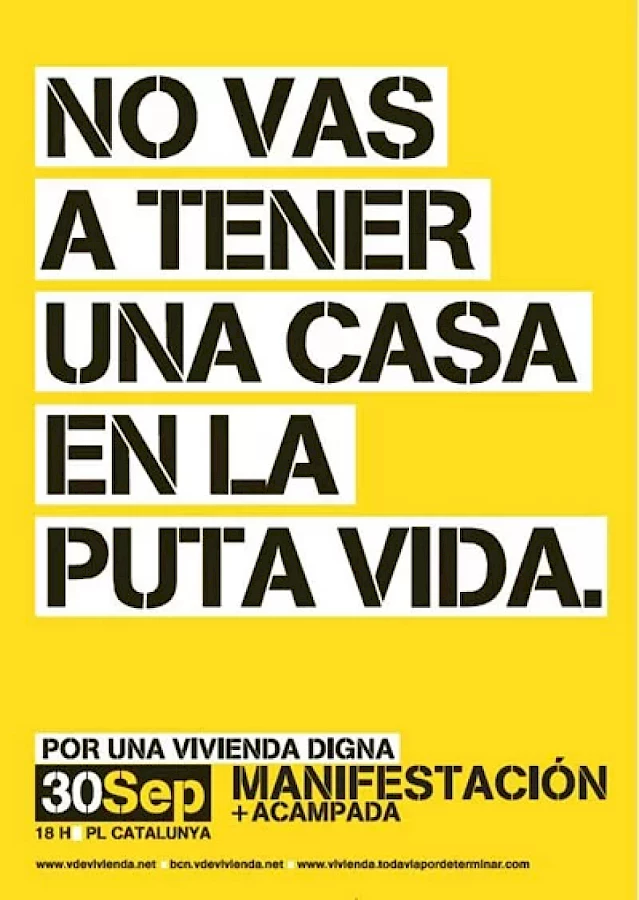

After several attempts, we soon realised that trying to find common ground was impossible. People did not come to those rallies moved by a common ideology. They were not just leftists or rightists, and, even if they were, those demonstrations were not characterised by that, any more than they were by gender, age or race. On the outside, those rallies were radically heterogeneous. So, we decided to change the plan and started looking for something common to everyone on the inside. We asked hundreds of different people what they felt when they were confronted with the housing crisis in one way or another. We wanted to see if there was something inside all those very different people that somehow worked as a commonplace, a common ground we could use as the basis for an imaginary that represented us at the most basic level. And yes, there was. Deep inside ourselves we all felt that we were never going to own a home in our fucking lives.

Poster "No vas a tener casa en la puta vida" (You'll never own a house in your fucking life) (author: V de Vivienda, 2004).

We took that feeling and turned it into a slogan: ‘You’ll never own a home in your fucking life.’ We printed it on posters, stickers and T-shirts, and that phrase automatically became V de vivienda’s rallying cry. For a while it was truly impossible to walk down the street without bumping into it. Thousands of people identified with it, and it was not an easy slogan. It certainly broke with the common sense that usually accompanies other slogans used by social movements. It offered no hope (‘Yes we can’); it offered no future (‘For a future without poverty’); it offered no alternatives (‘Another world is possible’); and yet it gave one the feeling that no one but oneself was hiding behind it. ‘I read it and I hear myself’, a person once said to me when I gave him the sticker in the street. ‘That’s exactly what I think: I’m not ever going to own a house in my fucking life.’

In addition to a lot of visibility, that phrase managed to give V de vivienda a big boost. With it, we were able to organise much more massive rallies and demonstrations. For more than a year, thousands of people were shouting our slogan at the top of their lungs in squares and streets all over Spain. But we had the impression that our cries were getting us nowhere. That is why we decided to break the world record for people shouting ‘I’ll never own a home in my fucking life.’

One day we called the people at Guinness World Records and asked to have our feat officially entered into their famous book. We explained our idea in detail, telling them that it would be carried out at the same time in several cities throughout Spain and that everything would be live-streamed. They assessed our proposal for a couple of weeks and finally rejected it ‘for being too weird’. They called us weird! Anyway, we didn’t give it a second thought and went ahead with our plan. We made a few videos and distributed them on the net as a call to arms. We also designed the Putómetro (Fuckmeter), an app that measured the level of anger someone felt in connection with a specific situation. On 6 October 2007, thousands of people gathered in the main squares of several Spanish cities and their shouts reached the maximum level of the Putómetro, setting the first world record for people shouting ‘I’ll never own a home in my fucking life’ at the same time. But not even this could prevent the economic crisis from reaching every corner of the world shortly thereafter.

That was when we created Enmedio (Amid). In addition to Oriana and I, who had been working together since Las Agencias, and Mario Ortega, who had been involved in the latter days of Yomango, Anja Steidinger, Jesús Cuadra, Daniel Bobadilla, Xavier Artigas, Núria Campabadal, David Proto and Toni Valdés joined this new adventure, as well as many other collaborators such as David Morgado, Elena Fraj, Samuel Esteban, Penélope Thomaidi, Patricia López, Nico Hache and Kevin Buckland.

The name Enmedio was an attempt to escape the names, or terms, that limit and reduce the experience of what we do. It refers to the fact that we value our work from a place established by ourselves, according to our needs and desires, and not by those imposed upon us by cultural institutions or professional artists. Enmedio means acting in the terrain we inhabit, trying to open paths where none existed before. Paths everywhere, amid everything.

Party at the INEM office

At first, the crisis was just a state of mind; a sort of social sadness and existential insecurity that paralyzed everything. It was as if, suddenly, the dreams represented daily by advertising had become completely unattainable, and people, frustrated and resentful, had begun to feel fear; a fear that seeped through the pores and filled the bones with dirty smoke.

We never fully believed in the financial crisis. We always saw it more as a tool of governance. Rather than a crisis, we were facing a triumph of crisis capitalism, a mode of government that ensured the permanence and the reproduction of profit by spreading fear everywhere. Fear was the essential symbolic strategy to achieve ‘quietism’ and to subjugate a population broken into a thousand pieces. This is what really worried us, that fear would prevail over joy. That was the main political problem for us, and we decided to confront it.

On 30 April 2009 we had a big party at an employment office. The first thing you need to do to organise a party is choose the right place. The INEM (Instituto Nacional de Empleo) office seemed ideal. Is there any other place where sadness and social fear are more present than an employment office? Unemployment is fear, isolation and stigmatisation; unemployment is the literal embodiment of sadness and social depression, just what we wanted to fight with our party.

So we went there one morning with our sound system, and the result was amazing. In less than five minutes of dancing and partying, all the long faces of the people in the unemployment line turned to laughter. The video we shot there became much more famous than we ever expected. Today it has more than one million views, and has been the inspiration for many other parties that have since been held from time to time in employment offices all over the country.

In order to scare us, capitalism insists on the belief that we have something to lose. If our party at the INEM office showed something, it is that the only thing we should really be worried about losing is the enjoyment and the joy of being alive.

We Are Not Numbers

One of the earliest manifestations of the crisis (crisis capitalism) was the evictions. Over the first three years of the crisis there were more than 350,000 evictions in Spain; some 532 a day, or approximately one every eight minutes. That’s how the media talked about them, as numbers. But the evicted are not numbers; they are people, with faces and eyes.

The ‘We Are Not Numbers’ project originated at ‘¡TAF!’ (Taller de Acción Fotográfica, Photographic Action Workshop), a workshop Oriana had been teaching at the Enmedio centre on an almost permanent basis for a few years. At ‘TAF!’ we investigated the infinite possibilities to intervene in social conflicts that photography offers. ‘We Are Not Numbers’ was created in collaboration with the Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (Platform for People Affected by Mortgages, PAH) and its goal was always to confront the housing problem: literally.

It achieved this in three different ways. Firstly, ‘We Are Not Numbers’ was a meeting place for people who were about to be evicted from their homes. The loss of a home is something that utterly destabilises a life. An eviction always affects the whole of family life, work, health; it is the dynamite that blows up the mental stability of anyone who suffers it. Those attending our workshop were all in a very vulnerable place. In those circumstances, the need for support becomes absolutely essential. Our workshop was first and foremost about responding to this need.

"No somos números/We are Not Numbers" (author: Enmedio, 2011).

Secondly, ‘We Are Not Numbers’ was a photography workshop. The participants, all of them threatened with imminent eviction, learned some basic portrait photography techniques, as well as some cheap printing methods. When the portraits were ready and printed large, the third and last part of the project began: the public intervention part.

Our interventions with ’We Are Not Numbers’ sought to establish a visual connection between all those people who were about to lose their homes and those directly responsible for their eviction. The person in the picture was the one who stuck their image to the facade of the bank that wanted to evict them from their home, and they did so accompanied by many other people who were in the same situation.

This act not only helped in identifying those responsible for an unfair system, but also gave those affected a great deal of power. This ritual, repeated countless times, not only gave strength, dignity and self-esteem to those affected, but also helped many people to understand the problem of evictions at a glance and, therefore, to support the struggle of those affected. Moreover, the continuous media coverage of these interventions forced banks to cancel some of the most imminent evictions.

‘We Are Not Numbers’ was one of those collective rituals that humans have been practicing since the beginning of time. It was an act of magic that used (self-) representation to confront the powerful forces battering us; an act of collective presence that, through the use of images, stood against the heralds of death, surviving the most adverse circumstances. Cave-dwelling humans did something similar when they used blood and ashes to depict themselves dancing around the fire, spears in hand, as a way to face the dangers that lurked in the deepest darkness of the night.

Yes we can, but they don’t want to

With the PAH, we also launched the slogan and graphic campaign ‘Sí se puede pero no quieren’ (Yes we can, but they don’t want to). The PAH had just placed a bill before the Congress of Deputies (Congreso de los Diputados) that included three specific measures to guarantee the right to housing in Spain: social rent, retroactive payment in kind and the immediate halting of all evictions.

Contrary to what one might think, the greatest inconvenience of placing a bill before the Congress is not having to collect the 500,000 signatures required (the PAH collected three times as many); it is getting the deputies to greenlight and approve the bill. The PAH thought that the only way to achieve something like this was to ensure the deputies really understood the dramatic consequences that a negative vote could have. That is why it repeatedly invited all deputies to its meetings, so it could explain to them in person the situation of those affected by the crisis. But unfortunately not a single deputy accepted those invitations. The PAH was running out of ideas when someone suddenly remembered the Argentine escraches.

In Argentina, the term ‘escrache’ is used to describe a peaceful demonstration in which a group of people congregate before someone’s home or workplace with the intention of publicly denouncing them, either as the perpetrator of a criminal act or to expose their responsibility in a political event. Adapting this same practice to feed live information on the situations of emergency in which thousands of people found themselves to the Spanish deputies seemed like a good idea. You know, if the mountain does not come to me…

However, it was a big leap from a ‘Stop Evictions’ bill to escraches for the PAH, and not without dangers for them. They had to determine how to properly convey the meaning and intentions of this proposal, or they ran the risk of being misinterpreted. That was precisely where we came into the picture.

Carrying out an escrache campaign is not easy; you face a series of very difficult challenges. First of all, we had to make it clear that, rather than pointing the finger at anyone in particular, the PAH’s escraches were intended to showcase and transmit the great social support that there was for their proposals. This forced us to invent a visual device capable of creating a friendly environment while, at the same time, showing all the hope contained in the Bill, at a glance. Second, we were working with a social movement (the PAH) that had itself, over the years, created a whole visual universe (the colour green, the ‘Yes we can’ slogan, etc.) that was already deeply rooted in the collective imagination, and from which we could not detach ourselves. Finally, the campaign had to work throughout Spain, and this forced us to design something light and easy to reproduce on a large scale.

Finally, the result was two circular cardboard buttons, one green and one red, each one metre in diameter. The green one read ‘Yes we can’ and the red one read ‘But they don’t want to’. Rather than trying to invent something new, we chose the opposite approach: to reinforce what already existed. This is a common practice in our line of work. We believe creativity can be found there, in the infinite combinations offered by the things that already exist, rather than in a pretended originality born in who knows what parallel universe. We decided to make the buttons out of cardboard because it was the cheapest material we could find, and that also responded to our creative demand: that the things we make must be capable of being easily appropriated by anyone. This is why we worked with circles, because even a fool can make an ‘O’ shape, and because the deputies press round on-screen buttons when they vote in the assembly: green circles for, red circles against.

On the other hand, since we are of the opinion that if something is not broken we should not fix it, we kept the ‘Yes we can’ slogan intact. We only added ‘But they don’t want to’. It seemed to us that this perfectly represented the conflict faced by the PAH, after more than two years of fighting against evictions and having placed a bill before the Congress: there are solutions to the housing problem, but a small group of politicians has the power to block them.

The campaign was completed with green stickers reading ‘Yes we can’ and including a summary of the basic proposals included in the bill. These stickers were designed so that businesses and establishments could show their support for the PAH by sticking them on their windows, if they wanted to. To facilitate the distribution of all these materials, we devised the Escrache Kit, a file accessible from the PAH website that included everything necessary for everyone to be able to build the two green and red buttons at home by following some simple instructions. In short: two recurring phrases, two simple shapes, two basic colours; nothing that could not be done by everyone. Yes we can!

World champions of unemployment

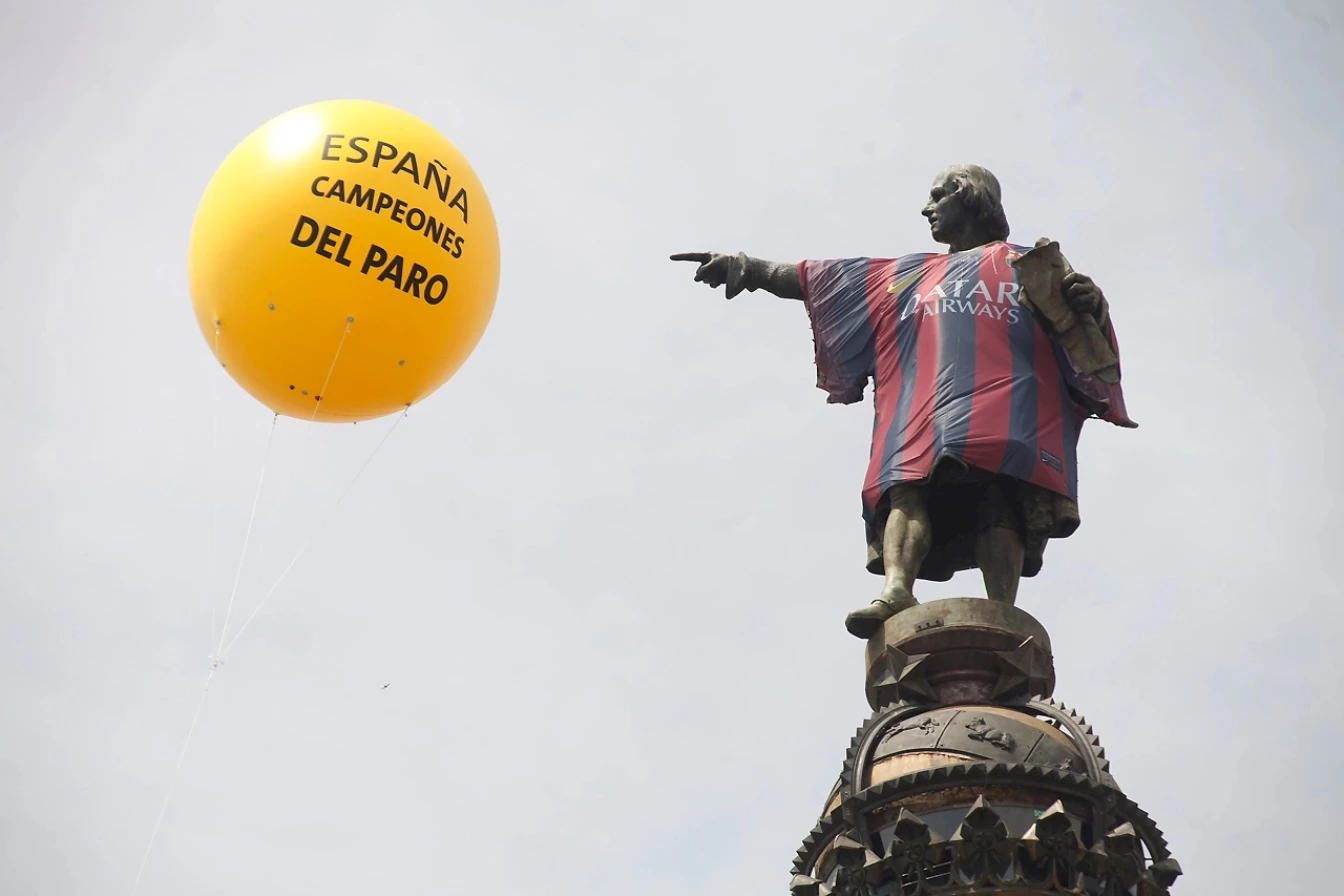

With the crisis came the privatisation of the public sector. Everything public was at risk of becoming private: universities, hospitals and even historical monuments. In June 2013, Barcelona’s city council, then presided over by the now-defunct Convergencia i Unió (Convergence and Union) party, rented the city’s monumental statue of Columbus to two multinational companies for use as a billboard, and for a good sum. They dressed the sculpture in a huge FC Barcelona T-shirt and used it to advertise sneakers and low-cost tourist destinations. This campaign went around the world. In just a few days, it was on the main TV channels and the covers of some of the most popular magazines. Its success put Spain back in the international spotlight, highlighting once again what the country is best known for: its sporting victories.

"Campeones del paro / Champions of unemployment" (author: Enmedio, 2013).

Spain is a world champion in almost everything: football, basketball, motorcycle racing; everybody knows that. What is perhaps not so well known, because it is never mentioned in the media, is that Spain is also a world champion of unemployment. At the time when we carried out our action there were more than six million unemployed persons in our country, almost half of the young people of working age. And that was something that deserved to be advertised.

When a company uses a monument such as Barcelona’s Columbus statue for commercial purposes, it triggers at least two immediate reactions. On the one hand, it adds a new meaning to the monument, giving it a new sense, a new interpretation; on the other hand, it puts a spotlight on it. And since no sign is ever fully closed, every sign is constantly open to new meanings, as long as one is able to intervene in it. From that moment on, any intervention focused on that same monument would have a similar (but different) effect.

The first thing we did was call the press and summon them to the foot of the Columbus monument at 12 a.m., the time when there are the most tourists in the area. Since the press had already spilled rivers of ink on the privatisation of this monument, everything related to it aroused great interest. So all the journalists we called showed up on time, eager to capture whatever was going to happen there with their cameras. And what happened was that, suddenly, a gigantic yellow balloon appeared on the scene, bearing the phrase ‘Spain, world champions of unemployment’ in both Spanish and English.

The journalists rushed to photograph the sphere as it rose through the air to the tip of Columbus’s finger, creating an image so irresistible that none of them could fight the desire to capture it. That is how we managed to sneak an advertisement of Spain’s alarming social situation into the press without spending a céntimo on publicity. And if the original campaign, that of Columbus the football player advertising sportswear and low-cost flights, had achieved great media coverage, our interventions did not follow far behind. Once again, Roland Barthes’s maxim was proven true: ‘It is always more subversive to alter a sign than to try to destroy it.’

Reflectors Against Evil

During the time of the crisis we did everything we could, even becoming superheroes at times. Rather than being a group as such, Reflectors Against Evil was a creative technique that anyone could use whenever they needed to, whenever they could take no more and said ‘Enough! This is the end of the line.’ We Reflectors Against Evil were ordinary people. We did not have what one could call superpowers; we had never mutated because of some strange scientific accident, we could not fly, we did not have superhuman strength. The only thing we had that made us a little bit extraordinary was some shiny suits and a couple of curious tools that we designed ourselves (with the help of the German group Tools for Action). Those tools were the Reflective Beam and the Infallible Inflatable, or Reflector Cube,1 two very simple things that everyone could make at home with little effort.

The Reflective Beam is a silver, lightning-shaped object used to reflect sunlight and prevent the police from filming people at demonstrations. The Infallible Inflatable is a very light but gigantic silver cube that can withstand extremely intense blows. It is designed to serve three purposes: First, to point out Evil wherever found, by adopting a thousand different shapes. Second, to entertain people when demonstrations become boring (which is quite often). Third, to stop the police from charging against demonstrators, which is the main reason why we created it.

We tried it for the first time in Barcelona during the general strike of 2011. Plaça de Catalunya was full of people enjoying the strike when the riot police arrived, hitting demonstrators left and right. That scene of terror caught us playing with our Infallible Inflatable and we could think of nothing to do but to throw it at the police. It was a real deus ex machina. The unexpected presence of that strange object was like that timely eclipse that appears in the movies when no one expects it, allowing the hero to escape. It completely immobilised the agents, who stood there not knowing what to do. First they tried to destroy it with their batons, but when that did not work they ended up throwing it back at us. We then threw it back to them, creating a sort of ping-pong match that turned that scene of terror into a real laughable scene. It was in this fortuitous way that we discovered the anti-repressive potential of the Inflatable Cube. That same day, back in our studio, we started mass-producing the Inflatable Cube and shortly thereafter we were testing them at demonstrations all over Europe, with consistently excellent results.

Cierra Bankia

In early 2012, Bankia, one of the largest banks in Spain, filed for bankruptcy. It then asked the Spanish government for twenty-three billion euros to be able to continue doing business, and their request was accepted without a second thought. That same week, the government cut twenty billion euros from the annual health and education budgets. The same politicians who had managed Bankia for years and brought it to bankruptcy were now the ones who decided, without asking anyone, to invest a huge amount of public money to bail it out. That was the straw that broke the camel’s back. From that moment, many people began to understand that what the media called an economic crisis was, really, a monumental swindle. More than a mere economic fact, the crisis became a political technique that, far from weakening neoliberal policies, as many then believed, led to their reinforcement.

This reinforcement came in the form of destructive austerity plans and bank bailouts. ‘Crisis’ now meant shutting up and obeying every command they gave us, and we were not willing to do either. That is why we organised the surprise ‘Cierra Bankia’ (Close Bankia) party, to get rid of the anger we were carrying around after hearing the news of the Bankia bailout. It was an action that we carried out in two distinct phases. First, we wrote and published a statement encouraging all Bankia customers to close their personal accounts. ‘It is better for Bankia to go under than for all of us to go down with it’, we told them. Then, once the statement gained momentum in social networks and some official media, we went to the vicinity of a Bankia office and stayed hidden until a young woman entered and closed her account.

"Reflectantes contra el Mal / Reflectors Against Evil" (author: Enmedio, 2012).

When she did, dozens of people appeared by surprise, celebrating her decision in style. Music, champagne, confetti; nobody had ever had such a party inside a bank before. The girl, who was more than astonished, ended up flying out the door while the rest of us (except the bank’s director, of course) sang ‘¡Bankia, cierra Bankia!’ (‘Bankia, close Bankia!’) in unison, a tune we wrote for the occasion which later became the official chant of the demonstrations against the budget cuts. The whole party at the bank was developed according to a predefined script, although not entirely so, as improvisation always plays a key role in this kind of intervention. During the workshops we organised in the days leading to this action, I remember, everyone defined and rehearsed the performance they would give on the day.

The repercussions of this action in the media were truly surprising; in a few hours, the video of the party got over one million likes. With a little creativity and a lot of fun we had been able to create an image capable of standing up to both the fear transmitted by the media (‘Don’t act, it could be worse’), and the mirage of security and trust on which any relationship with a bank is based (‘Trust us, we guarantee your future’). Somehow, the ‘Cierra Bankia’ (Close Bankia) party succeeded in transforming popular anger into a spark of fun without taking away one iota from the criticism of the budget cuts and the privatisation of public money. The fact that social protest can be fun, even in the worst of circumstances, inspired a lot of people to close their bank accounts with Bankia and to organise other ‘Close Bankia’ parties everywhere.

The Fence-World

From the day we held that party, the logic of neoliberal globalisation, exacerbated competition, job instability and the disturbing stagnation of high unemployment rates have only continued to increase fear. Fear is, today, the dark star of a comprehensive crisis that surrounds us on all sides, dragging down and dominating everything in the face of the extreme uncertainty of the future. Fear, more contagious than the plague, has slowly transformed the world into a fortified place full of exclusionary attitudes. It is a world increasingly defined on the basis of parameters of control and security, as the certainty of old ideas, political beliefs and the possibility of a better future, one of diverse and plural coexistence, weakens more and more. A world in which the social fabric is increasingly broken and security, surveillance and control are proclaimed as the only things with meaning. We at Enmedio are currently devoting our energies to imagining creative ways to confront these dark meanings of what we call the Fence-World: the world as a great fence made out of many fences.

What art, what activism can still stand up to the Fence-World? All the artistic experiments, public interventions and social processes that we developed in recent years are, in a way, attempts at answering this question. This is no easy task. How to be an activist when the truths that mobilised social action in the past have fallen, and reason no longer governs the organisation of life? How and where must we act to stop this free-for-all war, this classless class struggle that reduces us to a solitary and frightened crowd, ready to accept the most violent terms as a matter of course? With whom can we create alliances, groups or movements, when our lives are shattered, our identities ruined, a broken mirror that we try to put back together again and again? How can we still bet on social movements in a world without society, where solidarity and mutual support are nothing but a memory archived in the museum of ideas? How can one still be an activist in an inhuman world?

Attempting to answer these questions has led us to explore the vast propagation of neoliberal devices. Over the years, we have classified them into two main groups: 1) intensification devices, and 2) division devices. The first ones are all those devices that the powerful deploy to intensify and capture social energy. They take the form of desires, insatiable drives that always want more and more. The ultimate consequence of being constantly exposed to these kinds of devices is exhaustion, fatigue and anger. The second ones are those separatist impulses that now exist in all kinds of social relations, from the closest and most intimate to the most global ones. The equilibrium that holds between all the separate elements of global society is maintained through the use of control, surveillance and organised violence.

This set of two categories of devices encompasses everything, or almost everything, in and about the Fence-World. From the psychic to the physical; from the mental to the material; from its ideas to its infrastructure; together, they co-create the Fence-World as a space that attracts and repels at the same time. And it is this that we have set out to confront over the coming years. We are currently preparing a publication and a series of workshops where we will explore some possible ways of subverting it, of loosening our unhealthy ties to it. You will hear about these actions, for sure.