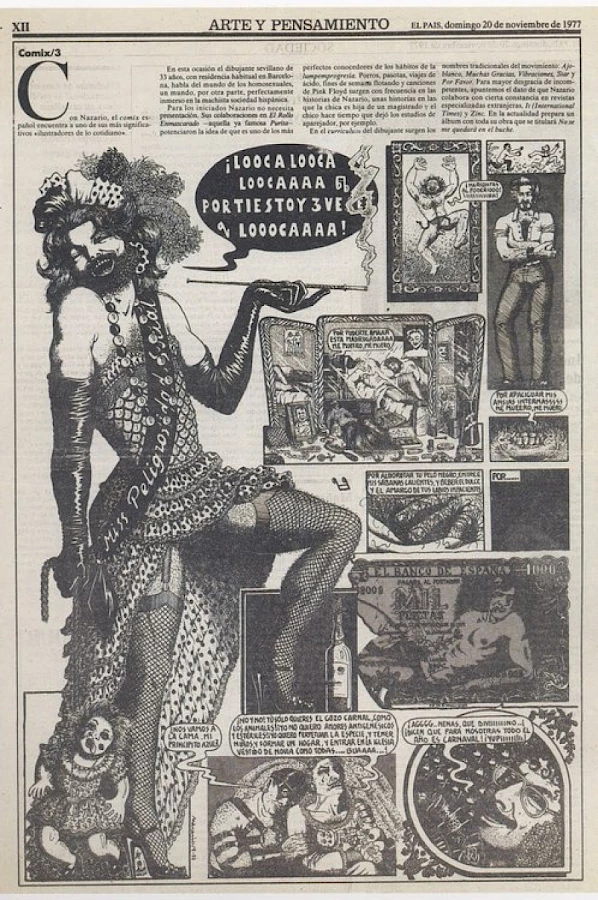

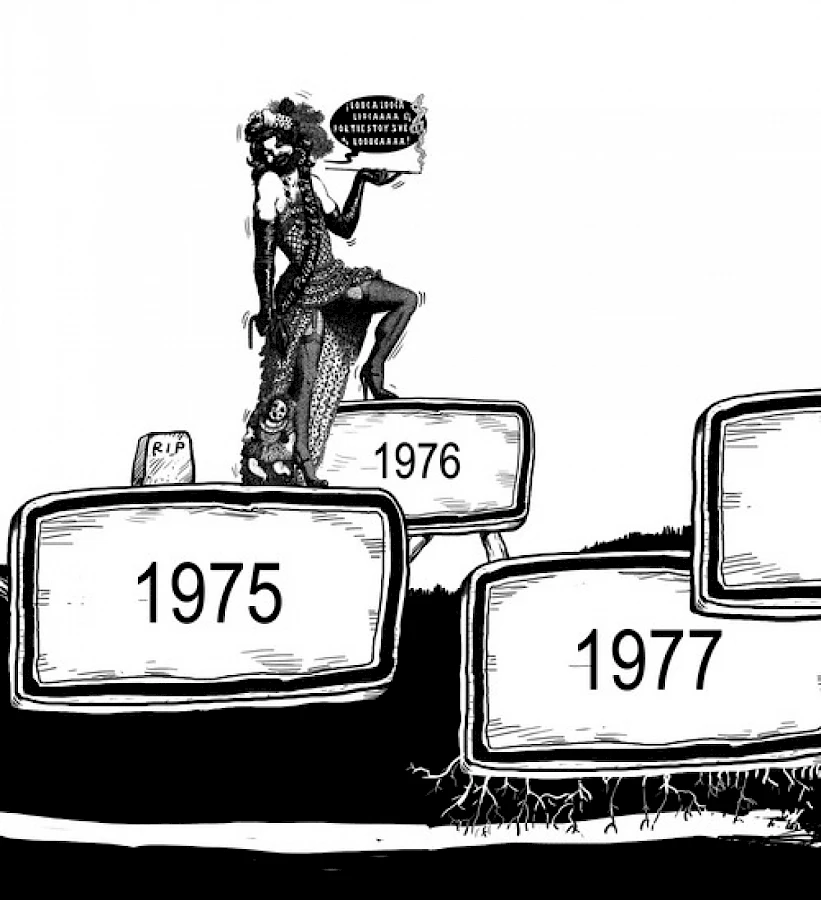

"Crazy, crazy, crazy, I'm three times craaaazy for youuuu...", sang Miss Social Dangerousness in a famous cartoon by the illustrator Nazario, one of the leaders of the protests by gay groups in Spain back in 1977 when Spain's legal apparatus was challenged by sexual minorities. Nazario, drawing published in El País, 20 November 1977.

Over two months after her initial arrest on 30 December 2014, the artist Tania Bruguera remains in Havana, where she has been released with charges and had her passport confiscated. A prosecutor will have to rule on the charges against her: incitement to disorderly conduct, disobedience, and incitement to commit a crime. In a statement on 4 February this year, Bruguera spoke out against the fact that for all practical purposes there is no separation of legislative, executive and judicial powers in Cuba, resulting in the extreme vulnerability of citizens like herself who are 'victims of the abuse of state power'.

But a cursory look at the current Cuban criminal code, which includes concepts such as 'pre-criminal social dangerousness' suffices to show that the vulnerability of citizens is actually written into the legal apparatus itself. This is the letter of the law: Law No. 62, Chapter XI: Dangerousness and security measures: 'ARTICLE 72. Dangerousness refers to an individual's particular proclivity to commit crimes, as shown by behaviour that expressly contradicts the norms of socialist morality. ARTICLE 73. 1. Danger is considered to exist when any of the following indicators of dangerousness is observed in the subject: a) habitual drunkenness or dipsomania; b) drug addiction; c) anti-social behaviour. 2. Anyone who habitually breaks the rules of social coexistence through acts of violence, or by other provocative acts, violates the rights of others, or who by his or her general conduct violates the rules of social co-existence or disturbs the order of the community, or lives as a social parasite from the work of others, or exploits or practices socially reproachable vices, is considered to be socially dangerous by virtue of such anti-social conduct. ARTICLE 74. Furthermore, dangerousness is considered the condition of the mentally disturbed individuals and of those mentally retarded should, by virtue of this reason, neither have the power to understand the scope of their actions nor to control their behaviour, insofar as they represent a threat for the security of individuals or of the social.'

Further along, the same law lays down the pre-criminal security measures in ARTICLE 78: 'Whoever is declared to be in a state of dangerousness in the corresponding process shall be subject to the most appropriate of the following pre-criminal security measures: a) therapeutic measures; b) re-educational measures; c) measures of surveillance by the agencies of the National Revolutionary Police Force.'

In the final years of Franco's dictatorship, the Spanish criminal code expanded its web of contrrol through the Law of Dangerousness and Social Rehabilitation, which was enacted by Francisco Franco in August 1970 to replace the Vagrancy Act that had been passed in 1933, and which expanded the notion of dangerousness to include: habitual vagabonds, homosexuals, prostitutes, illegal immigrants, drunkards, drug addicts, beggars, the mentally ill. The security measures stipulated by the law included confinement in 'a place of work', 'a re-education centre', or 'an internment centre until cured', 'remedial isolation', and 'submission to surveillance by the authorities', among others.

As soon as the dictatorship ended, various groups and activists fought these provisions, forcing a series of amendments to be made until it was finally abolished in full in 1995. This abolishment had been one of the principal political demands in Spain in the seventies. To this end, the first demonstration by gay, lesbian, and trans groups against the 'Law of Social Dangerousness' took place in 1977.

Antonio Gagliano, fragment of the MetaMap produced in the framework of the workshop Social Dangerousness. Sexual Minorities, Languages and Practices in 70s and 80s Spain, directed by Xavier Antich and Beatriz Preciado in the 2008–2009 MACBA Independent Studies Programme (PEI).

Curiously enough, a similar legal device was enacted in Cuba ten years later, borrowing the status of a 'dangerousness' and the assumption of a 'proclivity' for crime. From this legal vantage point, political dissidents are construed as dangerous subjects. And while the 1987 Cuban legislation does not directly mention homosexuality, it has nonetheless been criminalised in practice through the ambiguous potential for interpretation of the meaning of 'socialist morality'. In addition, with varying degrees of condescension, both laws include the 'mentally ill' or 'insane' person. Moreover, in both Franco's Spain and Castro's Cuba, the security measures applicable to 'dangerousness' range from therapy to intensive surveillance.

As Michel Foucault pointed out in his series of lectures entitled Abnormal at the Collége de France in 1974–75, the notion of 'danger' and of the 'dangerous individual' is used to justify the link between the medical and legal institutions, creating the theoretical core of the medical-legal expert opinion. The supposedly 'dangerous' individual is criminalised and also pathologized (either before or after). Some people would take Tania Bruguera's announcement that she was planning a performance in Havana's Plaza de la Revolución to be a sign that she is crazy. Where fear prevails, political disobedience appears like madness.

Translated from Spanish by Nuria Rodríguez Riestra