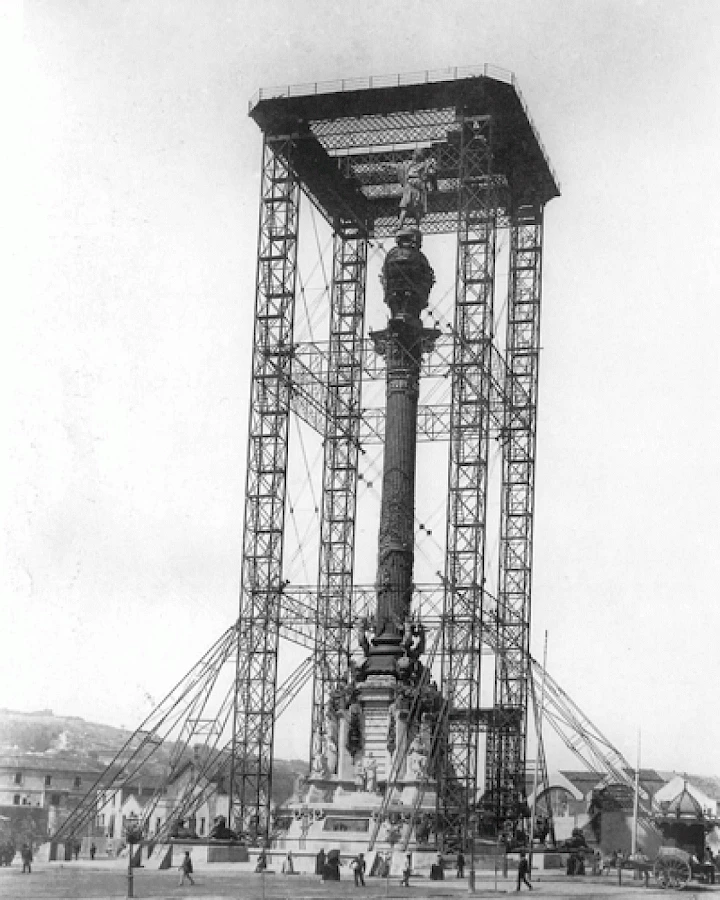

Construction of the Columbus Monument during the Universal Exposition in Barcelona, 1888.

In Spain, Columbus celebration – as an explicit activation of a colonial unconscious– began to take public shape in 1888. The first public sculpture of the navigator, who according to Jesús Carrillo had been a figure of "structural neglect"1 in Spain's past, was unveiled as part of the Barcelona Universal Exposition that year. Columbus was not part of the Spanish colonial discourse, which saw him as a foreigner and not particularly loyal to the Catholic Monarchs. Restoring Columbus was an 'importation' aimed at integrating into the new European and North American hegemony. The Columbus statue by Gaietà Buïgas then literally pointed its finger at the African destination of the Imperial enterprise of the time, showing the consolidation of a system of North-South inequality. The staging of the colonial drunkenness continued in Madrid in 1892, not only with a second sculpture in honour of Columbus as well as a Historical-European and Historical-American Exhibitions, inaugurated by the Monarchs of Spain and Portugal. This mainly involved a human exhibition that formed part of the parade organised in conjunction with the shows, in which some actors dressed as Native American Indians gravely thanked the solemn Catholic Monarchs and Columbus. This episode gave rise to the popular Spanish expression hacer el indio, to 'play the Indian', meaning to 'play the fool'. We shouldn't forget that not far away from this avenue, live human exhibitions of Filipino, Ashanti and Inuit people were being staged at the Parque del Retiro at around the same time.

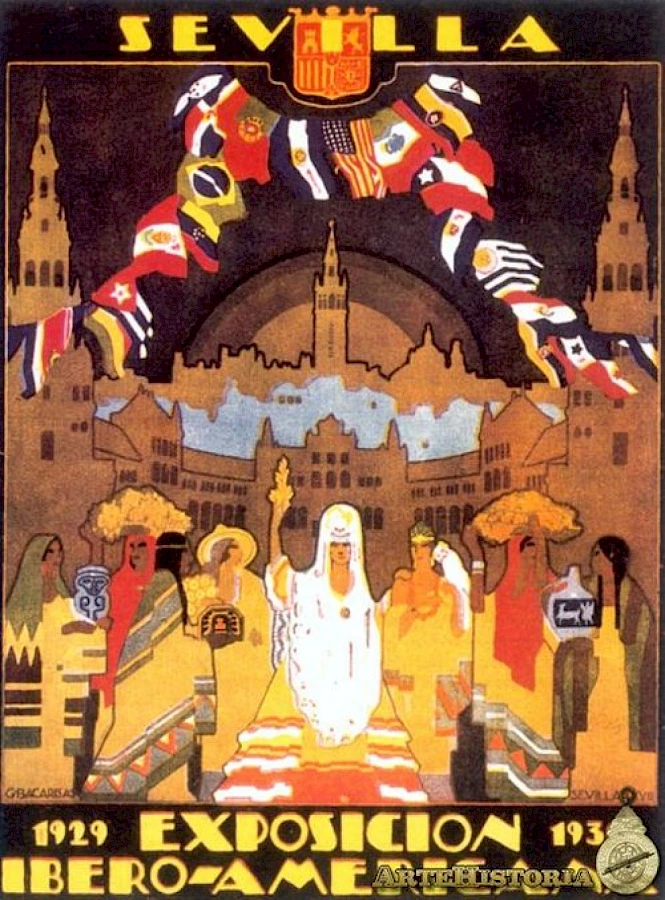

Poster for the Ibero-American Exhibition in Seville 1929, Gustavo Bacarisas.

The alcohol poisoning of the Spanish colonial unconscious came with the Ibero-American Exposition of 1929 in Seville, younger sister of the International Exposition held in Barcelona's Montjuïc that same year. No colony or former colony participated in this 'international' World Fair, even though the main thoroughfare that ran through the exhibition from Plaça d'Espanya was named Avenida de América to mark the occasion. The Ibero-American Exposition in Seville, on the other hand, included pavilions from Latin American countries, built in syncretic and indigenous styles that perpetuated the distinction between them and Iberian visual culture, which was crowned with the Plaza de los Conquistadores. The Ibero-American Exhibition also included a Macau Pavilion – a remnant of Portuguese colonialism in Asia – a Morocco Pavilion, a Moorish Quarter, and a Colonial Pavilion representing Spain's possessions in Equatorial Guinea, this latter one with its own live human exhibition.

Still from Pabellon de Guinea en la Expocicion Iberoamericana de Sevilla de 1929. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pax5yMNAW-Q

All of this was taking place against a political backdrop led by the dictator Primo de Rivera, who was promoting a new economic imperialism in the former colonies backed by a conservative, catholic ideology, which had led him to go as far as creating a Spanish 'national day'; the Día de la Raza or Day of the Race; on October 12. Years later, an institutional system for the promotion of cultural relations with former colonies was set up during Franco's dictatorship, with clearly political goals, in the form of five government entities: the Hispanic Council (1940), the Museum of America (1941), the Museum of Africa (1945), and the Institute of Hispanic Culture (1946), as well as the Hispanic-American Biennials (1951–1956).

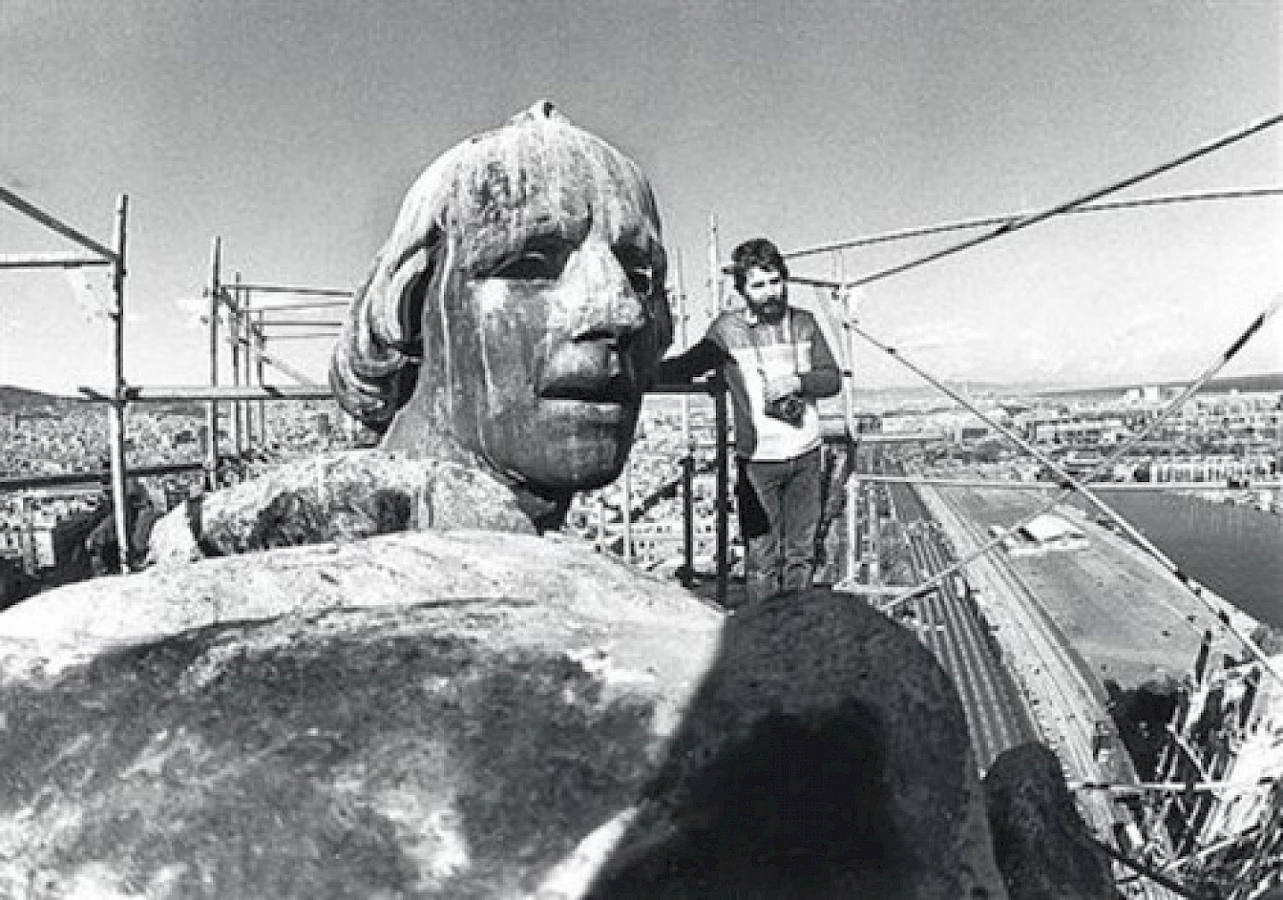

Pepe Encinas, Self Portrait at the top of the Columbus Monument, Barcelona, 1981.

Columbus, how can we Cut Off your Heads?

In the late eighties, some cultural agents started to suffer and to reverse the pain of this long Columbus hangover. The artists' group Agustín Parejo School, for example, carried out poetic activations of both the Latin American and the African colonial hangovers. In 1989, they modified the back page of issue 0 of the magazine Arena Internacional, with a map of the Sahara desert broken by a vinyl record containing the Paul Bowles piece REH BENI BOUHYA, recorded in Segangan, in the Sahara desert. Three years later, they invented a parodic Ecuadorian painter called Lenin Cumbe, and invited him to participate in the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo in Sevilla during the Universal Exposition of the supposed 'Encounter of Two Worlds': more inebriation disguised as modernising good will. These projects emanate from a new wave that looked to the art scenes in New York and Northern Europe for an art that was critical of their own time. This new generation of intellectuals and artists intervened the local scene with public actions, publications, and exhibitions that intended to rescue Spanish art from its provincialism and connect it to international debate. In this context, it is not surprising that a text by Homi K. Bhabha, "The postmodern and the postcolonial", was published in conjunction with the exhibition Plus Ultra in 1992, and that Gerardo Mosquera had started to contribute to the magazine Lápiz in the mid-eighties, with texts such as "The Third World and Western Culture" (1989), and "The Marco Polo Syndrome" (1992).

While that period could be read as a time of urgent transference in response to the sense of a lack of critical tools, over the past five years we have seen a different process of collective, affective, parodic and highly sceptical appropriation of knowledge stemming from experiences and histories shaped by another colonial past and present. Given the absence of academic debate around the postcolonial issue –except tangentially, in 'area studies'– and its sporadic appearance in the museum world, the Columbus hangover appears to be a life experience that confront the systems of knowledge/power in which it operates. This could clearly be seen on day three of the seminar Decolonising the Museum, which was recently organised by MACBA in the framework of L'Internationale, when, as part of the Península platform, we joined other 'local agents' in a session called 'Decolonial Practices, Activism, and Networks'. All the participants that day agreed that it is necessary to fight against the presence of the 'colonial wound' in every day life.

Created on 12 October 2012, Península is a group of about 40 members, who suggest research nodes at the intersection of colonial processes and exhibitions, the cultural industries, archives, migrations, and radical sexualities, to mention just a few. With no predefined objectives and no budget of its own, Península works on the basis of the drives, affects, and pressing issues that turn the need for reflection/action into an engine for questioning the systems in which agents operate in today, and the history of art and culture in the long historical memory of Spanish and Portuguese colonisation, as was clearly shown at a recent seminar at Museo Reina Sofia entitled Internal Colonialism and Citizenship in the South. Also this year, the group Declinación Magnética was born out of the project Decolonial Aesthetics, organised by Matadero Madrid with the theoretical support of Goldsmiths University. Other like-minded research-action groups have also recently formed in Barcelona, including Diásporas Críticas and Ira Sudaka, joining the artistic practices of individual artists who are dealing with the same issues, as discussed in previous posts on this blog. Also in 2012, Maria Iñigo and Yayo Aznar organised the congress History With No Past: Counterimages of the Spain/Latin America Coloniality at Centro de Arte 2 de Mayo in Móstoles, Madrid, and Olga Fernández with Clare Carolin organised Coloniality, Curating and Contemporary Art at La Rábida in Huelva.

In exhibition terms, the effects of all of this action have been both alcohol poisoning and hangover. In the first sense, the show Painting from the Viceroyalties - Shared Identities in the Hispanic World at Museo del Prado and the Royal Palace in Madrid was clearly a colonising liquor. On the other hand, in spite of their hits and misses, exhibitions such as The Potosí Principle at Museo Reina Sofía, The Baroque D_Effect – Politics of the Hispanic Image at the CCCB in Barcelona, and Ultrópics at the Pontevendra Biennial were like a stomach pumping of the colonial alcoholism, organised against the backdrop of commemorations of the supposed 200 years of the independence of Latin American countries in 2010. More recently, exhibitions such as Critique of Migrant Reason at La Casa Encendida in Madrid and Apocryphal Colony – Images of Coloniality in Spain at MUSAC in León used different strategies to act upon this pressing need.

Meanwhile, people working through activist practices have also been taking action to denounce the violence of contemporary colonial life. Organisation-action groups such as CalÁfrica, which works with African migrants, and Territorio Doméstico, which focuses on migrant domestic workers, and associations such as Espacio del Inmigrante Raval, Asociación de Sin Papeles, Ferrocarril Clandestino and Migrantes Transgresorxs have struggled the increasingly acute processes of discrimination and death affecting people from the former Third World. There are also various gypsy associations that fight the stereotypes and discrimination of internal colonialism, particularly the Association of Feminist Gypsy Women in Favour of Diversity which has, for example, spoken out against the racism of the Royal Academy of the Spanish Language which includes among its definitions of 'gypsy' a person who 'steals, or acts with dishonest intentions'.

These artistic, curatorial, or activist practices – or crosses between some or all of them – have been a recent process in which Columbus takes on a physical presence in the lives of those of us who have been marked by his historical power. Hence the pressing need for actions that confront colonial conflict, beyond the remoteness of the idea of ghosts that stalk memories from the past. We know that these ghosts remain alive in the present, in the colonial processes that cut across our bodies and exceed the levelling and distancing potential of any possible 'boom' of these debates in the international art system. Ultimately, it is about hangover bodies, furious at a global system located in the histories of Iberian imperialism, hoping to cut off all of the heads of Columbus and his henchmen.

Translated by Nuria Rodríguez