Five Rocks: A Collection of Tales

The following short story is set inside the Wall of occupied Palestine. Here, drones, sent by Israelis settlers to survey the land, buzz overhead. Asad, an old donkey shoots one down with a catapult. Hawks capture the flying machines and hold them ransom, whilst jumping gazelles defiantly fall in love beyond the shadow of the Wall. ‘Five Rocks: A Collection of Tales’ was co-commissioned with Wiels for their publication Magical Realism: Imagining Natural Dis/order (2025).

1.

The drone didn’t know it was a drone. Nobody had told it. Nobody had explained that its buzzing little propellers weren’t wings and that the endless scanning of hills and faces wasn’t what anyone would call a life. But if it could think – and sometimes it felt like it could – it would have thought of itself as something special.

This drone wasn’t just any drone. It was a test drone. It hadn’t yet been promoted to spray chemical fertilisers or pesticides, monitor soil hydration or do anything of that sort. So instead, it hovered over the terraced hills, harassing people in an almost-human voice for their ID numbers and their iris scans, constantly stalking them, frequently asking them to leave wherever they were. When it got really ambitious, it scanned the ground for movement, in case anything dared to grow back. It didn’t feel important, but it was efficient, which, in this line of work, was practically the same thing.

The test drone flew over the Wall onto a patch of flattened dead ground. It had been dead for years. Nothing grew there except stubborn little shrubs that didn’t know when to quit. The drone’s operators would call this ‘buffer zone management’, which was just a fancy way of saying they didn’t want anyone or anything to feel too comfortable unless they were strategically placed, trigger-happy soldiers.

High above, Fathi, a blue lizard, had been watching it all unfold. He was a skinny little thing, with a missing toe on his left front foot, though no one had ever asked how he had lost it. He spent his days sunbathing on a lone fig tree, one of the few living things left in the area. Fathi had been there long enough to remember what the land looked like before all of this. He missed the smell of herbs and the crunch of fresh leaves, but mostly he missed the bugs. Bugs were juicy. Bugs were gone now.

The drone hovered lower, its mechanical brain humming with calculations. ‘Scan complete,’ it announced to no one in particular. ‘No unauthorised vegetation detected.’ Fathi squinted up at it from the tree, chewing on a dry blade of grass.

Just then, the drone dipped too close to a branch, and Fathi’s survival instincts kicked in. He darted to the branch’s edge and flicked his tail hard, knocking loose a pebble the size of a walnut. The pebble fell, bounced off another branch and hit the drone squarely on its shiny black camera. A rock to the face.

The drone spun in a sad little circle. Its propellers sputtered. For a moment, it seemed like it might recover. But then it tilted sideways and plummeted with an unceremonious thud into a patch of brittle thistles.

On the other side of the Wall, a sibling drone kept buzzing, spraying fertilisers onto export crops, oblivious to its counterpart lying in a heap. Fathi couldn’t have cared less. Instead, he flicked his tail and closed his eyes, letting the sun soak into his blue scales.

2.

It was a spring day, a Friday, at noon, and all hell was about to break loose in Kafr Ghneim. The sun was shining over the rocky terraced hills on the outskirts of the village; the goats were grazing and behaving themselves for once, their sleek bodies scattered across the hills, shadowed by the Wall. The air was thick with the usual sounds of pastoral life: bleating, rocks crunching underfoot and a faint sound of Umm Kulthum singing ‘patience has its limits’ – the mosque’s speaker occasionally caught a rogue radio channel.

Then, a little whirring buzzing little bastard showed up from the other side of the Wall, hovering above them and ruining the sky. ‘La hawla wala quwwata illa billah’ (There is no power and no strength except with Allah). Abu Khalil didn’t have to look up to know it came from a group of settlers hiding on top of the hill across the valley. The drone flew low, casting its shadow over the flock. The flock was frightened and scattered. A double shadow.

Abu Khalil’s donkey, Asad, meaning lion, stood tethered to a carob tree. He was chewing lazily on the straps of an old leather slingshot. Abu Khalil had hung it there to keep it out of reach of the goats. The drone inched closer, whirring loudly enough that it irritated the usually nonchalant Asad. In a moment of anger, he kicked a rock onto the slingshot and tugged hard at its straps with a bite and a flick of his head. The rock arched perfectly through the sky, as if guided by some celestial force, and smacked the drone with a loud clunk. Sparks flew, and the drone crashed into a thorn bush nearby. The goats got back to their grazing, more cautiously this time.

Abu Khalil spotted a military jeep that had started making its way towards them. He told Asad: ‘If anyone asks, you did that. I’m too old for this shit.’

3.

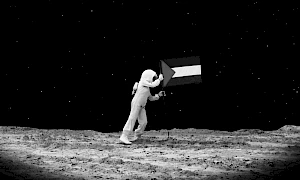

When you are a gazelle, love is a biological imperative. It surges through your synapses, pumps through your four-chambered heart and drives your hooves to dance like sun rays on a wheat field. That’s what it was like for me – Noura. Beyond the Wall.

The Wall is a snake with razor scales, growing and going where it pleases. It devours paths, caves, families and valleys. Layers of barbed wire spiral across its edges. Below, a trench four metres wide and four metres deep. On the other side of the trench, a patrol road smelling like jeep tires. Beside it, a sandy road recording our steps. For creatures like me, the Wall gnaws at the invisible threads keeping the world alive: the gene flow, the migration routes and the delicate dance of predator and prey. Even birds avoid it. Since its construction, there isn’t much left on the side where I live, save a brittle husk, overgrazed and exhausted, scattered with thorny bushes.

Beyond the Wall, Salah’s world is an open plain of olive trees, moonlit groves, thyme-covered slopes and overflowing springs that glisten under the sun. The horizon lays open. Or so he says.

Our love? It evolved in the narrow band of overlap when the drones were distracted, the soldiers tired. Our niche. Our ecotone. It began with a scent: volatile organic compounds released by his glandular secretions carried by the northern wind. A chemical message that bypassed my cerebrum and activated the limbic system. My heart rate increased. My rumen churned nervously. I knew instinctively: this was not a pheromone I could ignore. I traced the scent to the Wall, and that’s when I noticed something different: a gap no larger than the width of my flank, low on the ground and hidden behind a bush.

Carefully, I moved closer, my hooves crunching against loose gravel. The air near the gap was musky and sharp. I lowered my head to sniff. It was just wide enough for me to squeeze through, emerging on the other side. And that’s when I first saw him.

The sun glinted off his dorsal stripe, a bold contrast of tawny and white. My heart rate spiked – a physiological response designed to prime me for escape or embrace. I chose the latter.

‘You jump well,’ I said, trying to sound unimpressed.

‘You’re . . . symmetrical,’ he replied.

He might as well have proposed.

We jumped into a field of wildflowers, where the Wall’s shadow couldn’t quite reach. There, we twirled and bounded, our keratin-tipped hooves barely touching the ground. The thrill of leaping into the unknown filled the cracks that years of confinement had carved into my heart.

In the distance, a small herd of gazelles emerged, their leaps high and wild, cutting arcs through the air with grace. The kind of grace that makes you feel like you’ve been doing life all wrong. Naturally, we moved to join them. The sight pulled us forward instinctively. The sun warming our backs, the wind tugging at our fur. Then came a loud snap. Turning, we saw it lying there: a metallic winged body lay crumpled and broken on the ground, its red lights flickering pathetically as if to say, ‘Really? Out of all places, you chose to jump here?’ For a moment, we stared at it, unsure what to make of this broken thing. The herd was already shrinking into the horizon, and without another glance, we galloped forward, catching up. The wind sang in our ears, the horizon stretched endlessly and the machine lay forgotten, swallowed by the dust.

4.

An artist receives a new commission. It is a precious opportunity, the kind that could shape his career, or so he thinks. He carves a large stone sculpture in the town square, focused and determined. As he works, a piece of the stone chips off and flies into the air like a rocket. The artist doesn’t notice, lost in the work that he believes will be his salvation.

The fragment shoots upwards and clips a drone scanning the square. The drone spins wildly before crashing into a pile of tomatoes. A vendor shouts, ‘Ya khara, my tomatoes.’ The crash startles some fighting cats who scatter immediately but reassemble moments later as if nothing had happened.

A police officer steps forward and adjusts his holster. ‘Come,’ he says. ‘Let’s have a coffee at the station.’

5.

47 days into the arrival of the settlers, Amal climbed out of bed and staggered into the night, as she did every night since they had arrived, to undo the things they have done – the poisoned wells, the uprooted saplings, the salt scattered over the soil. She tended to her hakura, a small piece of land – bigger than a garden, smaller than a grove – where herbs flourished under the lemon tree and vegetables grew in the shade of the pomegranate and plum trees. The fig tree, planted before she was born, stood tallest, its branches spreading wide. She gave it room to breathe even as her world constricted. She looked at the surrounding settlement on the opposite hill, clean and stupid, like a sterilised bandage covering a festering wound. She thought of words that grounded her, that helped her hold on to some essence of life; marj, bayyara, karm, haql, beidar, bustan, juron. Seven words she could remember for ‘land’.

Despite her head full of silver hair, she was still fit and vital. Her face and hands were carved by the sun. Her height, the distance from the roots of her trees to their branches. Making a living used to mean movement. Now she was confined to half a dunum plot, with gravity on her back and feet bolted to the ground.

Their arrival was marked by the departure of birds. At the beginning, mornings became silent. Then came a cloud of strange grey metallic birds with red eyes, carried by the western wind. One day, she would wake up to dozens of them perched on a tree. She had learned to ignore them during the day and work in the cover of the night. She would kneel in the soil, brush away the salt they had scattered and plant a handful of seeds at the edge of her land, carefully pressing each one into the soil. They were seeds she had saved for years, for a moment like this. It did not matter if she would see them grow. What mattered was that they were in the ground.

It was the first light of dawn by the time she returned home to brew a cup of hot verbena tea to calm her nerves. She noticed two pigeons perched on the telephone lines. For the first time in a long time, she felt a rush as she grabbed some rice and a stale loaf of bread.

She tossed a piece of bread into the air for the pigeons. The drones didn’t like it. Their red eyes blinked furiously. One of them took to the sky and caught the piece mid-flight. Amal grabbed a fistful of rice and threw it once more to the birds. This time, the pigeons got their share.

The next day, the pigeons returned with more friends. And then, the next. As the weeks went by, more birds began to appear – sparrows first, then storks and hummingbirds. Finally, a brigade of hawks arrived from the south. Despite the pain of her tennis elbow from throwing rice and bread to the growing flocks night after night for months on end, Amal kept to her rituals – undoing the damage in the hakura, brewing the tea and feeding the birds.

One day, she heard a sharp cry and saw a hawk swoop down, talons extended, slicing through one of the drones as if it were paper. And another, capturing one of the drones and taking it back to its nest.

15 months and 20 captured drones later, the hawks managed to strike a deal – the captured drones in exchange for the complete withdrawal of the settlers. Amal stood in the hakura watching the settlement pack up as she munched on some figs.

Amal and the birds lived happily ever after.

Related activities

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

HDK-Valand

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Gothenburg

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and Mills Dray (HDK-Valand), 17h00, Glashuset

-

Moderna galerija

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Ljubljana

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Bojana Piškur (MG+MSUM) and Martin Pogačar (ZRC SAZU)

-

WIELS

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Subversive Film and Alex Reynolds, 19h00, Wiels Auditorium

-

NCAD

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Dublin

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and members of the L'Internationale Online editorial board: Maria Berríos, Sheena Barrett, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Sofia Dati, Sabel Gavaldon, Jasna Jaksic, Cathryn Klasto, Magda Lipska, Declan Long, Francisco Mateo Martínez Cabeza de Vaca, Bojana Piškur, Tove Posselt, Anne-Claire Schmitz, Ezgi Yurteri, Martin Pogacar, and Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, 18h00, Harry Clark Lecture Theatre, NCAD

-

–

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

WIELS

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels. Rana Issa and Shayma Nader

Join us at WIELS for an evening of fiction and poetry as part of L'Internationale Online's 'Collective Study in Times of Emergency' publishing series and public programmes. The series was launched in November 2023 in the wake of the onset of the genocide in Palestine and as a means to process its implications for the cultural sphere beyond the singular statement or utterance.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

–

International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People: Activities

To mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People and in conjunction with our collective text, we, the cultural workers of L'Internationale have compiled a list of programmes, actions and marches taking place accross Europe. Below you will find programmes organized by partner institutions as well as activities initaited by unions and grass roots organisations which we will be joining.

This is a live document and will be updated regularly.

-

–SALT

Screening: A Bunch of Questions with No Answers

This screening is part of a series of programs and actions taking place across L’Internationale partners to mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People.

A Bunch of Questions with No Answers (2025)

Alex Reynolds, Robert Ochshorn

23 hours 10 minutes

English; Turkish subtitles

Related contributions and publications

-

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Rewinding Internationalism

InternationalismsVan Abbemuseum -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Everything will stay the same if we don’t speak up

L’Internationale ConfederationEN caInternationalismsStatements and editorials -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Rethinking Comradeship from a Feminist Position

Leonida KovačSchoolsInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Broadcast: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency (for 24 hrs/Palestine)

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board, Rana Issa, L’Internationale Confederation, Vijay PrashadInternationalismsSonic and Cinema Commons -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

S come Silenzio

Maddalena FragnitoEN itInternationalismsSituated Organizations -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cinq pierres. Une suite de contes

Shayma Nader–EN nl frInternationalisms -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Speaking in Times of Genocide: Censorship, ‘social cohesion’ and the case of Khaled Sabsabi

Alissar SeylaInternationalisms -

Today, again, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalisms -

Isabella Hammad’ın icatları

Hazal ÖzvarışEN trInternationalisms -

To imagine a century on from the Nakba

Behçet ÇelikEN trInternationalisms -

Internationalisms: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardInternationalisms -

Dispatch: Institutional Critique in the Blurst of Times – On Refusal, Aesthetic Flattening, and the Politics of Looking Away

İrem GünaydınInternationalisms -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials